The Crazy Story Of Hans Schmidt, The Killer Priest

There are plenty of records that you might want to hold. Only athlete to play in both the Super Bowl and the World Series? Sounds good. Only thespian to have won three Oscars for Best Actor? Awesome.

Hans Schmidt holds one of those kinds of records, but it's not one you'd be jealous of. As The New York Daily News reports, Schmidt is the only Catholic priest to ever be executed.

In fact, Schmidt was very much unlike any Catholic priest you've ever known or heard about, even if your opinion of priests in general isn't very good. His story shocked the entire country more than a century ago, and even looking back from the modern day it's difficult to believe he actually existed. If Schmidt was a character in a gritty thriller novel, people would say he was too over-the-top.

But Schmidt did exist, and his story is one you won't forget. It involves literal blood lust, promiscuity, religious delusion, murder, and forbidden affairs — not to mention forgery, abuse, and creative interpretations of the Catholic Mass. In other words, here's the crazy story of Hans Schmidt, the killer priest.

Hans Schmidt's family had a history of mental illness

Hans Schmidt was born in Germany in 1881 to Heinrich and Gertrude Schmidt. Heinrich worked for the railroad, and Gertrude was a stay-at-home mother to their ten children, and the family was well-regarded in the small town of Aschaffenberg. But as historian Mark Gado notes, the Schmidt family showed a lot of signs of mental instability.

Most notably, Hans' mother, Gertrude, showed little capability for raising ten children more or less on her own. Heinrich was away a great deal, leaving it to Gertrude to take care of the household. She became depressed and began attending church services constantly, and when she wasn't at church she sat in her room reciting the rosary instead of cooking or caring for her children. And Heinrich had anger issues. A Protestant, Heinrich opposed his wife's Catholicism and would fly into terrible rages when he discovered she'd resumed attending mass when he went away on business trips. His rages prompted Hans to hide in his room.

But as Gado makes clear, the history of mental illness in the Schmidt family went much deeper. Hans' great-grandfather was an alcoholic who suffered a mental break, his great-uncle, great-aunt, and cousin all committed suicide, and another cousin spent the last portion of her life in a mental institution.

His parents were kind of crazy

Heinrich Schmidt was outwardly a well-respected member of German society. He had a good job with the local railroad and a well-tended property with a thriving garden that supplemented his family's groceries nicely.

But Heinrich had a dark secret — a terrifying temper. He was a man of fixed ideas about the proper ways to behave, and his solution to any whiff of disobedience from his family was to physically beat them. As historian Mark Gado notes, whenever his son's strange behavior came to Heinrich's attention, he would beat the boy in an attempt to discipline him. And when his wife, Gertrude, continued to practice the Catholic religion despite his stern disapproval, he would beat her mercilessly to discourage it.

Meanwhile, Hans Schmidt's mother was depressed and lonely and found solace retreating into religious fanaticism. She attended mass twice a day when her husband was away and spent much of her time in her room reciting the rosary. As reported by Hushed Up History, as Hans grew older, she would dress him in priestly clothes she made herself and practice the mass with him at a homemade altar they'd created. His nickname as a child was "The Little Priest" as a result.

Hans Schmidt was a very strict—and very bad—Catholic

You might think that anyone who enters the priesthood must be a very religious person and deeply committed Catholicism — and you would be right. After a childhood spent dressing as a priest and practicing the Catholic Mass with his mother in her bedroom, Hans Schmidt duly entered the seminary to study for the priesthood at the age of 19.

But as historian Mark Gado makes clear, Schmidt had some very strange ideas about what it meant to be a good Catholic. At a very young age, Schmidt began to explore his sexuality with both boys and girls despite the clear prohibition of the Catholic Church in such matters. In fact, Schmidt was bisexual and quite promiscuous his entire life, engaging in sexual affairs with men and women even after becoming a priest. As author Mark Grossman notes, he was having an affair with a man named Ernest Muret even after "marrying" a woman and fathering a child with her.

Worse, he was also a pedophile. Historian Mark Gado notes that he confessed to being obsessed with the altar boys who assisted him and even confessed to having impure thoughts about them. And then there's the whole thing where Schmidt murdered someone, which is a very un-Catholic thing to do.

As a child he was fascinated with human blood

There are often warning signs that someone is going to grow up to be disturbed. When it comes to Hans Schmidt, there were plenty of such signs.

Schmidt exhibited a disturbing affection for human blood and suffering from an early age. As reported by The New York Daily News, Schmidt spent much of his childhood hanging around slaughterhouses because he found the blood and suffering of the animals to be arousing, and he even used human blood in strange religious rituals he invented. According to historian Mark Gado, he and another boy named Fritz would meet at the slaughterhouse and engage in masturbation together, and he began to kill small animals like chickens and rabbits for his religious rituals. His father would beat him when he was caught lurking around the slaughterhouse, but it never deterred him for long.

Schmidt was often observed walking around at night, stopping suddenly and standing still for long periods, and frequently referred to hearing the "voice of God" in a very literal sense. As noted by Murder Revisited, Schmidt was obsessed with Catholic ritual from a very early age and liked to dress as a priest as a child, practicing the mass and other aspects of the religion with his mother. There were plenty of clues to Schmidt's mental instability.

Hans Schmidt was arrested for forgery

Some criminals are satisfied to focus on a single specialty. Hans Schmidt was the sort of criminal who had a wide variety of immoral and illegal interests. Aside from eventually becoming a murderer and a very, very bad priest, he was also an accomplished forger.

In fact, as historian Mark Gado reports, shortly before being ordained, Schmidt was arrested in Munich on charges of forging graduation certificates for students who had failed out of school. His father hired a lawyer for him, who successfully argued that Schmidt's family had a long history of mental illness and was therefore not responsible for his poor judgment. The argument worked, and Schmidt was sentenced to a month at a local sanitarium, and the church allowed him to continue his studies.

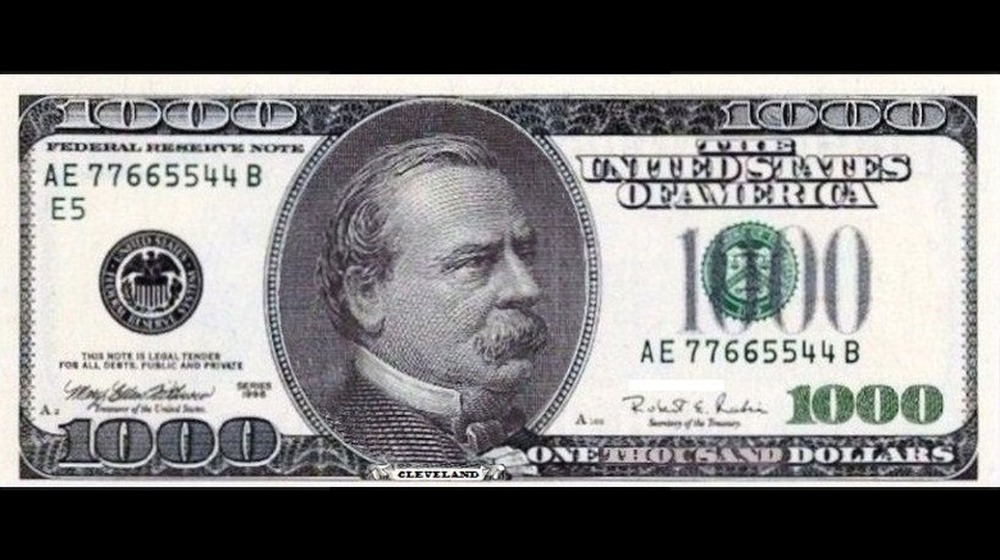

Later, while serving as a parish priest in New York, Schmidt continued to dabble in forgery and counterfeiting. As noted by Hushed Up History, Schmidt was involved in a counterfeiting ring in Harlem making fake $10 and $20 bills — but he wasn't terribly smart about it, as Gado reports that his $20 bills all had the same serial number, making them very easy to spot and trace.

He claimed he was ordained by a saint

By the time Hans Schmidt had completed his seminary studies and was ready to be ordained as a priest, his reputation was ruined in Germany. As historian Mark Gado recounts, because he'd already been arrested for forgery and had a reputation as a strange and unreliable man, his ordination was conducted by the bishop in private, with no witnesses or ceremony to mark what was typically a joyous occasion.

In fact, as Gado writes, just about everyone who had any experience with Schmidt had serious doubts about his fitness for the priesthood. By the time the bishop ordained him in Mainz, Germany, he had a reputation for having sexual affairs with both men and women and was a frequent guest of the local taverns.

When asked about his ordination, Schmidt often refused to speak about it, but he also claimed that the official ceremony didn't count — because his actual ordination had been conducted by Saint Elizabeth. "The real ordination took place the night before. St. Elizabeth, she ordained me herself," he said. "I was praying at my bedside when she appeared to me and said, 'I ordain you to the priesthood.' She then disappeared. There was light during her appearance."

Hans Schmidt got creative with the mass

Despite his obvious mental health issues and problematic behavior, Hans Schmidt was ordained a Catholic priest in 1906 and was assigned to the small village of Burgel in Germany. This did not go well. As historian Mark Gado notes, Schmidt seemed disinterested in his parishioners and often skipped services altogether, which upset the community.

Worse, as noted by The New York Daily News, Schmidt didn't stick to the Catholic script. As a village priest, he would often alter the mass to suit his own ideas, changing the rituals and the words according to his own ideas. This upset the villagers even more. As Gado writes, Schmidt's career was over just a few years after his ordination due to his eccentric approach to the mass, rumors of his many love affairs, and a habit of extorting money from elderly parishioners in exchange for promises of salvation.

Realizing that he was unlikely to receive any further assignments in Germany, Schmidt traveled to America in 1909 using money from his father, where he repeated all the behaviors that had ruined him in Germany — bizarre variations on the mass, love affairs, and petty theft. He was once again moved from parish to parish until finally landing in New York, where he would commit his most horrifying and sensational crime.

Hans Schmidt had an affair with a housekeeper

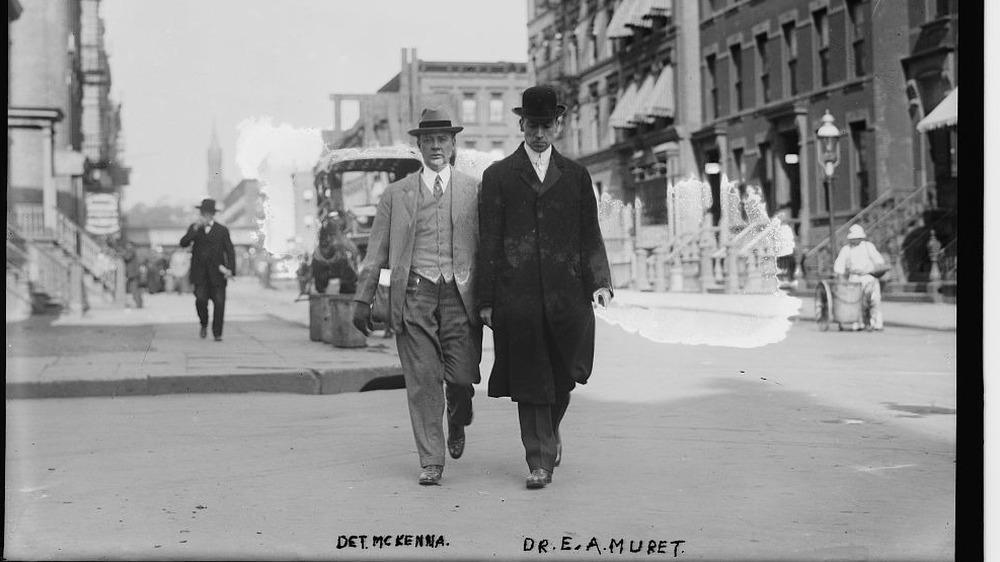

After arriving in America, Hans Schmidt served a short time at St. John's Roman Catholic Church in Louisville, Ky. As reported by Sword and Scale, Schmidt quickly got on the wrong side of the minister in charge in Kentucky and was forced once again to relocate. There are rumors that he was suspected in the death of a young girl and that he'd been caught running a counterfeiting operation in Kentucky, but those rumors were never fully investigated. Whether his rift with the minster was over crimes like that or simply a personal matter, Schmidt found his way to New York City and St. Boniface's parish where he met Anna Aumüller and Ernest Muret and began having love affairs with both simultaneously.

Aumüller was an immigrant from Austria, a strikingly attractive young woman who worked at St. Boniface as a housekeeper. She and Schmidt began having an affair shortly after his arrival, and as historian Mark Gado notes they even got married, with Schmidt officiating at his own illegitimate marriage. New York Almanack reports that Schmidt likely knew the marriage wasn't legal but went through with it to placate Aumüller, who was unhappy with their illegitimate status.

At the same time, as Gado notes, Schmidt began an affair with dentist Ernest Muret — with whom he also launched a fresh counterfeiting scheme. Schmidt felt very passionately about Muret, saying, "There was never a grown-up man I loved as I did Muret."

Hans Schmidt claimed God wanted him to kill

As reported by New York Almanack, when the dismembered body of a young woman was found along the shores of the Hudson River in 1913, it was quickly determined that she had been pregnant — about five months along. When the police identified the victim as Anna Aumüller, the secret wife of Father Hans Schmidt, the motive for the murder might seem obvious — it's one thing for a priest to keep a secret lover. It's something else to have a child and keep your priesthood.

But as reported by historian Mark Gado, Schmidt claimed that he'd been ordered to kill Aumüller — by God himself. He claimed to have been visited by Saint Elizabeth, who commanded him to make Aumüller into a "sacrifice." That sacrifice was exceptionally brutal — he knocked her unconscious and slashed her throat, then dragged her into the bathroom and set about dismembering her body and wrapping each piece in bundles of paper. Schmidt had studied surgery books and knew how to use a knife. Then he carried each bundle to the river, weighed it with stones, and tossed it in — presumably as Saint Elizabeth had commanded. He made an attempt to clean up the apartment but grew frustrated and left plenty of evidence behind, though he did burn the blood-stained mattress.

The murder investigation was very efficient

Modern-day police investigations seem slick and efficient with their CSI-style technology and access to the Internet. But the New York City Police Department in 1913 did a pretty incredible job investigating the murder of Anna Aumüller.

As reported by The New York Daily News, Aumüller's body was found cut up into several bundles — except her head, which was never located. This made identifying the body very difficult, but a sharp-eyed police detective noticed that one of the pillow cases used to dispose of the body had a tag on it. They found the shop where the linens had been bought and quickly found the apartment where Hans Schmidt had murdered Aumüller —rented out under his own name. As noted by Encyclopedia.com, the police found plenty of evidence of a crime there — bloodstains, the tools Schmidt had used to dismember Aumüller, and letters cluing them in to her identity.

According to New York Almanack, when detectives initially arrived at the parish to confront Schmidt, he denied knowing Aumüller at all. When he realized the police knew he'd rented the apartment, he admitted he knew her but claimed to only be helping a woman down on her luck. His story was plausible enough that the cops left to work the case more. When they returned the next day, Schmidt almost immediately confessed, claiming that he'd been ordered to kill Aumüller by Saint Elizabeth.

It took two trials to convict Hans Schmidt

The arrest and trial of Hans Schmidt was a sensation at the time — a Catholic priest accused of various sexual affairs and the murder of his mistress would be pretty big news even today, after all. But according to Psychiatric Times, Schmidt was confident he would be spared the worst and probably sent home to Germany because he was sure he would be found not guilty by reason of insanity.

Schmidt played up his claims of being sexually aroused by human blood and being commanded to kill by Saint Elizabeth. Rival teams of mental health professionals argued over his sanity, but as Encyclopedia.com reports the trial ended with a hung jury because no one could agree whether Schmidt was truly insane or play-acting to avoid the death penalty.

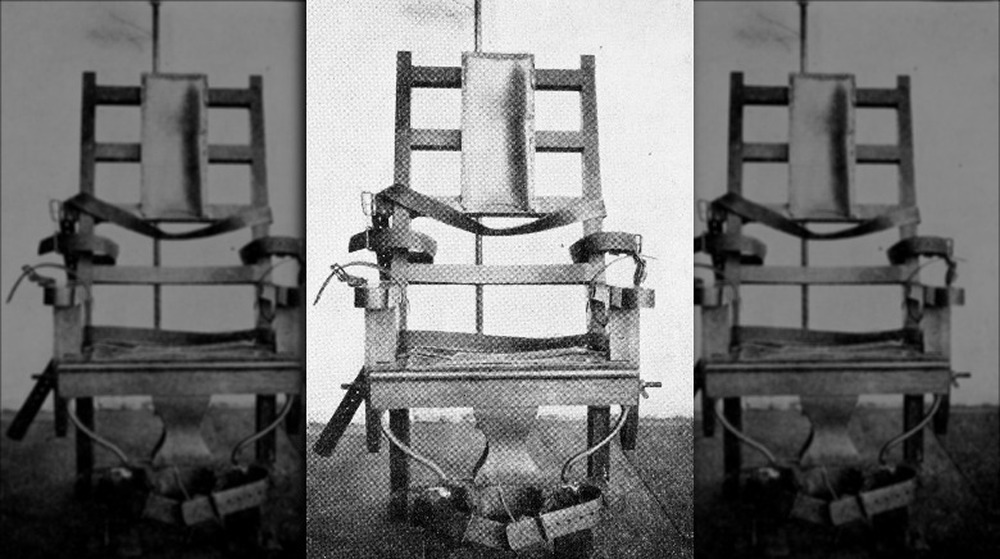

As historian Mark Gado notes, at the second trial a new piece of evidence changed everything — Schmidt had convinced Anna Aumüller to take out a life insurance policy worth $5,000, with Schmidt listed as the beneficiary. That convinced the second jury that he wasn't insane, and they duly convicted him of first degree murder in February 1914. Schmidt was sentenced to death.

His appeals failed

After his conviction for the murder of Anna Aumüller, Hans Schmidt's attorneys appealed — and Schmidt unveiled a new version of events in an attempt to escape his fate. As related by historian Mark Gado, he now claimed that he wasn't at all insane and that Aumüller had died while undergoing an illegal abortion conducted by several acquaintances of his. He claimed that her death had shocked them all, and they had disposed of her body rather than face the consequences. He further claimed that he had hidden all of this initially because he wished to protect his friends.

It didn't work. As noted by Psychiatric Times, the judge admitted that there was evidence that Aumüller had, in fact, undergone a botched abortion — but refused to order a new trial based on it. When Schmidt's lawyers tried to push the idea that his first two trials should be discounted because he was faking insanity, the judge rejected this because the jury, in finding him sane, had therefore made the correct decision.

It took two years, but after exhausting his appeals, Schmidt, the killer priest, was led to the electric chair in February 1916 and executed.