The Real Reason There Were So Many Assassinations In Germany After WWI

In 1918, with its allies defeated, Germany was forced to come to terms with the fact that it had lost World War I. With a revolution at home and a military that was no longer willing to fight, Kaiser Wilhelm, the German emperor, was forced to abdicate. In short order, the Big Four — Britain, France, the United States, and Italy — imposed their terms with the Treaty of Versailles, which called for Germany to accept the responsibility for "causing all the loss and damage" during the war, as well as accepting a series of extreme reform measures that would change Germany forever.

That confluence of war, defeat, abdication, and accepting all responsibility set the stage for an internal struggle for political power in Germany — much of which was fought by political assassination. Between the end of the war and the mid 1920s, right-wing extremist groups routinely carried out murders, while using racism, nationalism, and economic anxiety to stoke fear and hatred in the population. By 1922, more than 300 politicians and government officials had been murdered. All of it created a climate — and some say an appetite — for the Nazi Party, World War II, and the Holocaust.

Germany relied on right-wing paramilitary groups after World War I

Not only did Germany have to accept complete responsibility for the war, the country was forced to adopt a constitution, a new government structure, new borders, a disarmament plan, and massive reparations. Everyday Germans were angered by the severity of the reconstruction of their entire society, including the overwhelming economic reality of inflation and food shortages, per the BBC. All of it polarized the nation, with communist factions seizing control of the early days of the new government.

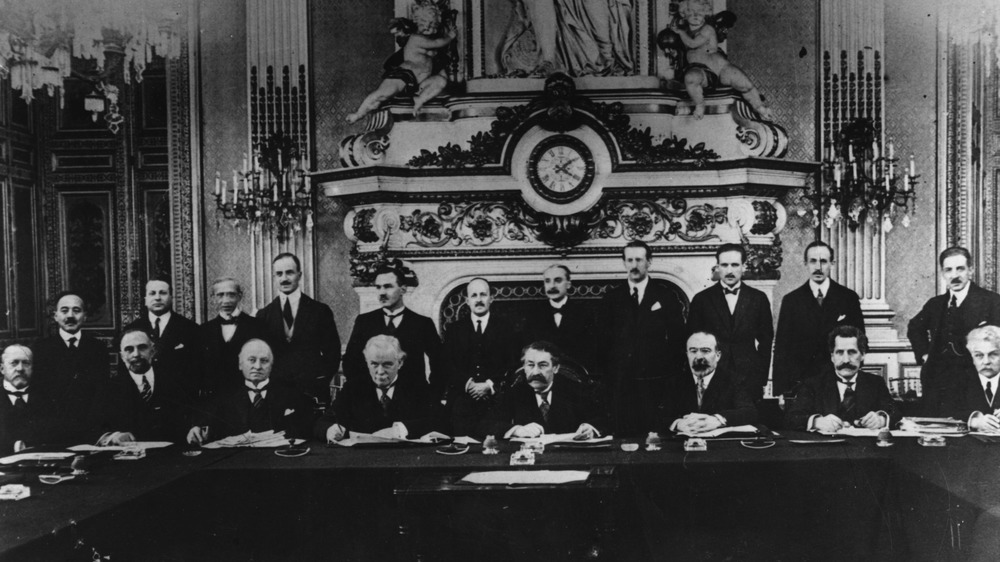

In response, private armies funded by former German army officers, called Freikorps (pictured above), fought back. These paramilitary groups, according to the World War II Museum, were staffed by Germans who had become disillusioned, including ordinary citizens who were resentful of Germany's surrender, former soldiers who were disgruntled that their government had capitulated on disarmament, and young men who were angry over the high levels of unemployment. As History.com notes, as many as 1.5 million German men would join a Freikorps group at some point.

However, as the government stabilized, it no longer needed to rely upon the Freikorps. But stabilization wasn't good enough for one hardcore faction within the Freikorps. An extremist right-wing paramilitary organization formed in 1920 known as the Organization Consul began murdering its political enemies, while pledging to preserve German nationalistic ideals, disrupt disarmament, destroy the new constitution, fight the influence of communism, and increase hostility toward Jews.

The Organization Consul targets high-level officials

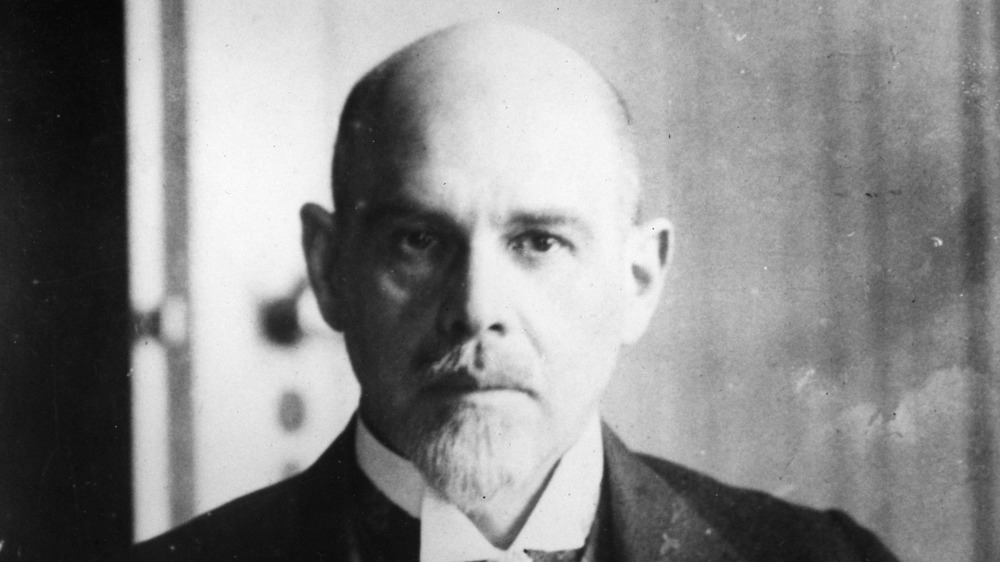

The Organization Consul's first target was Matthias Erzberger, Germany's minister of finance. The right in Germany was contemptuous of Erzberger for signing the Treaty of Versailles. They were also angry about the strict tax reforms he imposed upon the German citizens at a time of economic struggle. He was gunned down in 1921 by the Organization Consul while he was out for a walk at a spa in the Black Forest, sending a shock throughout Germany, The New York Times reported at the time. A year later, the group went after Walther Rathenau (pictured above), Germany's foreign minister. Rathenau was working to repair Germany's foreign relations, as well as its economy, but, as a Jew, the far right vilified him and his efforts. In June 1922, a machine gun-wielding Organization Consul assassin mowed him down at close range. It was celebrated among the far-right, while many in the rest of the country were left horrified, Haaretz noted.

In all, 354 politicians and government officials were killed by the end of 1922, according to Deutsche Welle. The group's activities were largely overlooked by the justice system, making little attempt to deter the killings. And it was even partially financed with government money set aside for the Freikorps. The government eventually banned the Organization Consul, but the damage was done. After the ban, it renamed itself, kept operating, and then aligned itself with the Nationalist Socialist Party — the organization that would eventually become the Nazis.