This Was The First Murder In Colonial America

Murder is an unfortunate fact of history. Through time and place, it seems almost inevitable that some member of our species will ultimately get the idea that they should end the life of another, whether it's for revenge, personal gain, or some other dark purpose. That's not to say it's right, only that it's very difficult indeed to find a community of people where everyone behaves themselves for an extended period of time.

The Puritans of Plymouth Colony were no exception. According to History, this group of religious separatists had landed in Massachusetts in 1620, believing that the Church of England wasn't doing the sort of work they wanted to see in the world. They also claimed that the non-Puritans of England and the Netherlands were on their case too much, so they left for the colonies of the New World to establish their own isolated settlement. After rough weather waylaid them, the group landed near Cape Cod and established Plymouth Colony in 1620.

Ten years later, in the waning months of 1630, a man named John Billington was hanged in Plymouth for the murder of John Newcomen. This gave him the rather dubious honor of becoming America's first known person to be executed for the crime. But, who was America's first recorded murderer? How did he fit into the Puritan way of life? And were the Puritans really as pure as they wanted everyone else to believe? What's the real story behind the first murder in colonial America?

John Billington was hanged for murder in 1630

John Billington, New World colonist, signer of the Mayflower Compact, and general troublemaker in the Puritan colonies, was hanged in September 1630. As Plymouth Colony reports, his crime was that of shooting fellow colonist John Newcomen in the woods near the colony.

No one recorded why, exactly, Billington would have shot Newcomen, though there is plenty of evidence that colony officials dithered as to Billington's eventual punishment. Governor William Bradford reached out to his fellow leaders, including Governor John Winthrop, seemingly asking for backup and reassurance that he was right to seek the death penalty. By then, Billington had already established himself as a thorn in the side of the burgeoning Puritan government.

For his part, Billington also may have believed that the colony didn't have the resources to try to execute him for the crime. Perhaps that was because, as Mayflower speculates, he thought he was justified after having an argument with Newcomen a few days prior, though we can't be sure as to the intensity or tenor of their disagreement. Meanwhile, Billington could have assumed that the small, struggling colony wouldn't dare to do away with a valuable laborer. He was very wrong. As Bradford later wrote, he determined that Billington had to die and "the land to be purged from blood" spilled by the man's crime.

Plymouth Colony wasn't above executing people

Whether or not John Billington believed that he would die, officials later proved that they weren't above executing criminals. According to the New England Historical Society, Plymouth Colony's General Court eventually put its laws into a formal code they called the "General Fundamentals". Within this code, colonists learned that, among all of the stuff about taxes and trials, quite a few offenses could get one hanged. These included crimes like murder, treason, sodomy, adultery, and witchcraft (which would come into tragic focus with the 1692-1693 Salem witch trials).

However, officials seem to have been more likely to whip, banish, or publicly shame people than have them killed. As per MayflowerHistory.com, that included punishment in the stocks and even large badges proclaiming one's crime, much like the red letter "A" worn by Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter.

The next murder trial after Billington's didn't come until 1638, when Arthur Peach and his associates were convicted of murdering a native Nipmuc man named Penowanyanquis. As the Library of Congress reports, a bleeding Penowanyanquis was able to describe his attackers before he died, saying that they had stabbed him with a rapier without provocation. Though the surviving records are fragmentary, we know that Peach and two other men were hanged for the murder, perhaps to appease local Narragansett people who were worried about white attacks on Native Americans. A fourth, less penitent man fled to Maine and was never apprehended.

John Billington's origins are mysterious

As much as the officials of Plymouth Colony wanted us to remember John Billington as a thorn in the side of good Puritans everywhere, there's precious little information about this colonial troublemaker's origins.

According to MayflowerHistory.com, it at least appears that Billington came from Lincolnshire, England, where his son Francis was named as the heir to a man named Francis Longland. That's about all the information we have of John or his family in Britain, though, leaving us to pick up the trail far across the Atlantic Ocean in New England.

Billington, who was apparently not a religious separatist like his Puritan neighbors, would have been one of a number of non-Puritan settlers who came to the colony and who may have chafed under strict Puritan rules. However, as The Washington Post reports, the Puritans had a more complicated view of how the state and religion should interact than you might think. They didn't exactly welcome other religious outsiders like the Quakers or other established Christian traditions, reserving much of their ire for Catholics. But neither did they establish a pure theocracy. If nothing else, their highly religious way of life eroded generation after generation, until their way of life became more story than lived experience.

The voyage was difficult for John Billington and other Mayflower passengers

The trip from England to colonial Massachusetts was pretty miserable for everyone aboard the Mayflower. According to History, travelers were originally going to make the passage on two ships, the Mayflower and the Speedwell, alongside some more secular folks. Puritans called themselves "Saints" in order to distinguish themselves from the "Strangers" who were traveling alongside them. Nearly as soon as they left the port of Southampton, England, the Speedwell began leaking. Everyone returned back to shore and crammed into the Mayflower.

Thanks to all this back-and-forth, not only was everyone now stuck on a ship that was a mere 80 feet long and 24 feet wide, but they were doing it at the stormiest time of year. One person was knocked overboard by a wave, though Bradford rather smugly wrote that God had done it because the victim has been "a proud and very profane yonge man." As for everyone else, seasickness was so rampant that many were left clutching their berths, unable even to walk.

Being stuck alongside the trash-talking John Billington and his family probably didn't make the passage any easier, though you get the sense that the Puritans were no fun themselves. Regardless of who deserves the most blame, everyone must have been relieved to tumble out of the Mayflower and onto shore when it landed after a grueling 66 days on the ocean.

John Billington was involved with near-disaster on the Mayflower

As if the trip across the Atlantic wasn't bad enough, thanks to rough weather, seasickness, and the general misery of being trapped with too many people on an 80-foot boat, disaster very nearly ruined everything before the Mayflower actually landed. And, presumably to everyone's non-surprise, the Billington family was involved.

As The Mayflower reports, the culprit this time wasn't John Billington but his son, 14-year-old Francis. While inside a cabin on the ship, Francis discharged his father's gun. A contemporary report, via the Pilgrim Hall Museum, says that Francis had been messing around with the gun and gunpowder, setting off a charge near an array of more gunpowder, berths, flints, and a variety of other flammable or spark-causing things. It could have sparked a deadly blaze, but, as the report states, "by God's mercy, no harm done." One imagines, however, that this all caused an ungodly ruckus and further set everyone against the Billingtons and their patriarch.

America's first murderer signed the Mayflower Compact

Perhaps it's possible that as much as records from the time would have you believe that John Billington was a major wrench thrown into the carefully calibrated machine of Puritan society as envisioned by its leaders, he wasn't all that terrible. If he was, would Billington have been one of the 41 men who signed the Mayflower Compact?

As per the Ancient History Encyclopedia, the Mayflower Compact was one of the first documents establishing just how Plymouth Colony intended to govern itself. Both "Saints" and "Strangers" signed the agreement, which was necessary after storms and poor navigation landed the group outside of the Virginia Company territory and its nascent legal system. The Puritans, who decided that Massachusetts was good enough — perhaps not fully understanding the winter ahead of them — therefore had to make their own rules of governance.

Though he was apparently understood to be one of the "true" Pilgrims who signed the Mayflower Compact, Billington didn't seem to be very dedicated to following the rules of government outlined in the historic document, as his later behavior would prove to the colony's leaders.

The Billingtons were religious oddballs in Plymouth

According to How Stuff Works, the Billingtons were apparently "Strangers" who traveled to America with the Puritans and weren't part of their sect. The Puritans were clearly rankled by the presence of people they considered to be outsiders, whom they must have assumed would ruin the whole separatist religious movement they had going on.

According to contemporary documents collected by the Pilgrim Hall Museum, the genesis of the Mayflower Compact was based on Puritan reactions to the non-Puritan "Strangers" among them. It was, as William Bradford wrote, "occasioned partly by the discontented and mutinous speeches that some of the strangers amongst them had let fall from them in the ship." The idea of non-Puritans like Billington doing what they pleased in the colony was so upsetting, it seems, that the Compact was brought into being before they even really made landfall.

As per How Stuff Works, it's also possible that Billington was Catholic, which would have rankled the Puritans, who were notoriously anti-Catholic. Indeed, religious upheaval is at the heart of American history, Smithsonian Magazine reports. Some settlements even banned "Papists" outright, along with other unapproved believers like Quakers, who were even hanged for practicing their particular religious beliefs alongside the officially approved Puritans.

John Billington was a known problem in Plymouth

John Billington seemed intent to cause trouble for the colony and its officials especially, at least going by the documents produced by said officials. Governor William Bradford, who really seemed to have a bone to pick with Billington, wrote to fellow leader Robert Cushman that "Billington still rails against you, and threatens to arrest you, I know not wherefore" (via Governor William Bradford's Letter Book). He then goes on to state, rather baldly, that "he is a knave and so will live and die." It's a rather chilling sentiment, given that the letter in question was written in 1625, years before Billington was hanged for murder.

Sometimes, all the bluster and trash-talking seem to have gotten Billington into actual trouble. Shortly after the Mayflower had landed, John Billington was already in hot water for running his mouth. As per the Pilgrim Hall Museum, he was publicly shamed in March 1621 for effectively talking back to captain and military commander Miles Standish. For his "opprobrious speeches," Billington was "adjudged to have his neck and heels tied together." The punishment only stopped when Billington apologized. Since officials knew this to be his first offense, they let him go, but this would prove to be only the beginning of his troublesomeness.

The whole Billington family was troublesome

Though it may seem like the colony had it in for John Billington, it was really his entire family that seemed to pop up whenever there was trouble in the settlement. Six years after his execution, John's wife, Eleanor, was sentenced after slandering a man named John Done. According to the Pilgrim Hall Museum, Eleanor, deemed "Helin Billington" in the Plymouth Colony record of this exchange, was whipped and put into the stocks, a form of public punishment that would have put her at the center of community shame and judgment. She was also fined £5. Yet, none of the records from this time contain details about what was said between Done and Billington.

Other Billington women were similarly punished for violating Puritan mores. How Stuff Works reports that Dorcas Billington, John's granddaughter, was also whipped after she was pinned with the charge of "fornication." Though it seems scandalous, it's worth remembering that sexual crimes like premarital canoodling weren't unheard-of even for the seemingly high and mighty Puritans. As the Plymouth Colony Archive Project points out, fornication came up again and again in Plymouth's legal system. Clearly, Dorcas wasn't alone, as quite a few Puritan folks were far from the squeaky clean do-gooders that many modern folks assume them to be.

John Billington Jr. was one of the first Plymouth settlers to peacefully contact local Native Americans

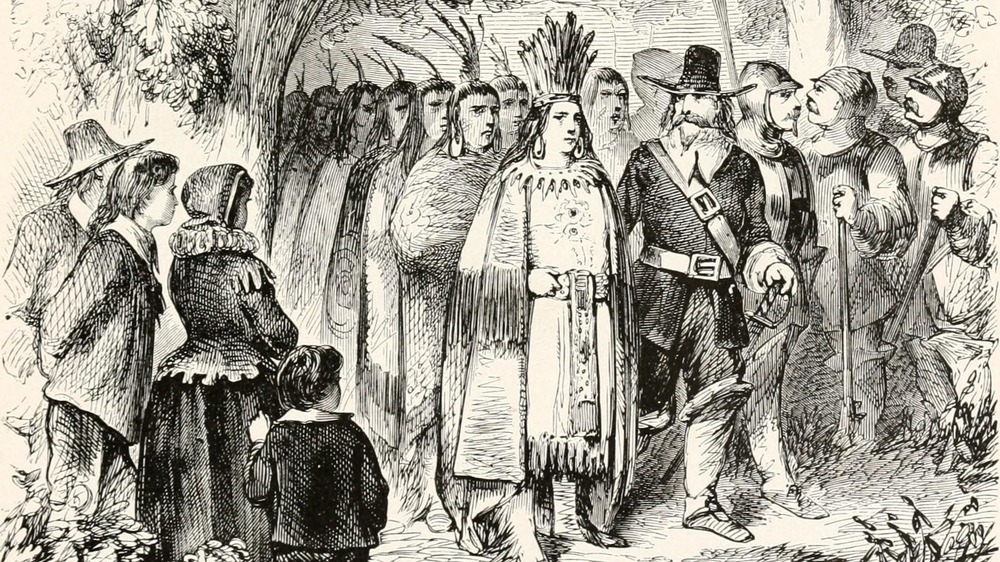

Though John Billington became notorious after his death as the first murderer in the colony, it turns out that his family wasn't all that bad. His son, also named John, may have inadvertently helped relations between the colonists and nearby Native Americans, in part because he got lost walking in the woods.

According to Mayflower Lives, John Billington Jr. was walking in the woods in May 1621 when he realized that he had gotten lost. He wandered some 20 miles south of Plymouth, surviving on berries he had foraged along the way, until he came across a village of Native Americans. The Native people took him to Cape Cod, where John Jr. stayed with the Nauset people. Eventually, word got out that a colonist had been recovered, and the people of Plymouth set out to retrieve young Billington. It was likely a voyage that was beset with some trepidation, as the colonists and the Native people hadn't enjoyed the most friendly relations.

Yet, things looked pretty hunky-dory when they set eyes on John. Accounts of the trip, relayed at the Pilgrim Hall Museum, say that the group was greeted by the sachem, or chief, Aspinet. He brought along the boy, who was "behung with beads," and peacefully transferred him to the colonists.

John Billington may have been an anti-government vigilante

Though many of the documents from this time period depict John Billington as a dangerous presence in Plymouth Colony, these accounts come from the leaders who were most bothered by him. The rest of the colonists didn't necessarily fall in line with their ideals and may not have viewed Billington as an unreformable "knave," as Governor William Bradford called him.

Billington was even implicated in a scandalous attempt to overthrow the colony's governors. As Plymouth Colony reports, Billington was tied to Reverend John Lyford and John Oldham, two notorious rebels. In 1624, Lyford had been caught sending letters back to England that were meant to undermine officials' power in the colony. When Bradford confronted him, Lyford said that he was only giving voice to more widespread dissent. Billington denied having anything to do with the affair, despite Oldham's assertion that he was definitely a part of it all. It's possible that Billington backed off because he did not want to be banished, as both Lyfrod and Oldham were.

It certainly seems as if the Puritans couldn't take any real dissent or criticism, given how happy they seemed to be to banish people who raised awkward questions, like Lyford or religious dissenter Anne Hutchinson. Per History, Hutchinson was banned in 1637, seven years after Billington's execution, for challenging the religious authority of the colony's men.

Some believe John Billington may have simply highlighted unrest in a troubled colony

Ultimately, the troubled, troublesome John Billington and his story may have been a symptom of a wider problem. His story hints that Plymouth Colony was less cohesive and more stressed than some would have us think.

Life in Plymouth Colony was no easy thing. American History notes that the colonists faced utterly miserable winters, full of freezing rain, hastily constructed homes, and dwindling food supplies. Illness killed about half of the colonists that first winter of 1620. They also scorned the advice of people like adventurer John Smith, who wrote that people in the New World should "use and endeavour to store yourselves of the native corn." Instead, the colonists first tried to plant seeds that they had brought from England and didn't pay attention to the seasonal ebb and flow of native foods until things got dire.

All of this struggle also meant that the colony eventually found itself in serious debt. As PBS reports, Plymouth had been funded by some 70 investors who wanted to be repaid eventually. Yet, despite the potential richness of the colony, with plenty of nearby timber and abundant fish and the potential for fur trapping, it took years for the settlement to find its feet. The debt no doubt added to an already stressful situation, and someone like Billington may have been given less grace and leeway than he would have gotten in a more prosperous time.