The Truth About The Industrial Revolution's Sewing Machine Wars

Before the Industrial Revolution and the invention of the sewing machine, making a shirt could take more than 14 hours. Creating a calico dress might require six-and-a-half hours. But once Elias Howe invented his revolutionary device in 1846, the time slashed to a little over an hour for the shirt and just 57 minutes for the frock, according to American Historama. The innovative gadget "changed the world by completely transforming and revolutionizing the shoe and clothing industry and the lives of ordinary people by providing the means to buy cheap, fashionable clothing," reported the website.

The difference in speed was remarkable, with the average hand sewn garment reaching 23 stitches per minute, whereas the sewing machine could do 250, according to America's Library.

Other sewing tools came out prior to Howe's. Fifty years before Howe's machine, Englishman Thomas Saint patented one, and close to that time, a Frenchman called Thimonnier also developed a version, said ThoughtCo. He actually used his to make Army uniforms, but Parisian tailors worried the machine might make their jobs obsolete, so a group stormed his workroom and broke them. Although Thimonnier recreated his invention, it never achieved widespread use.

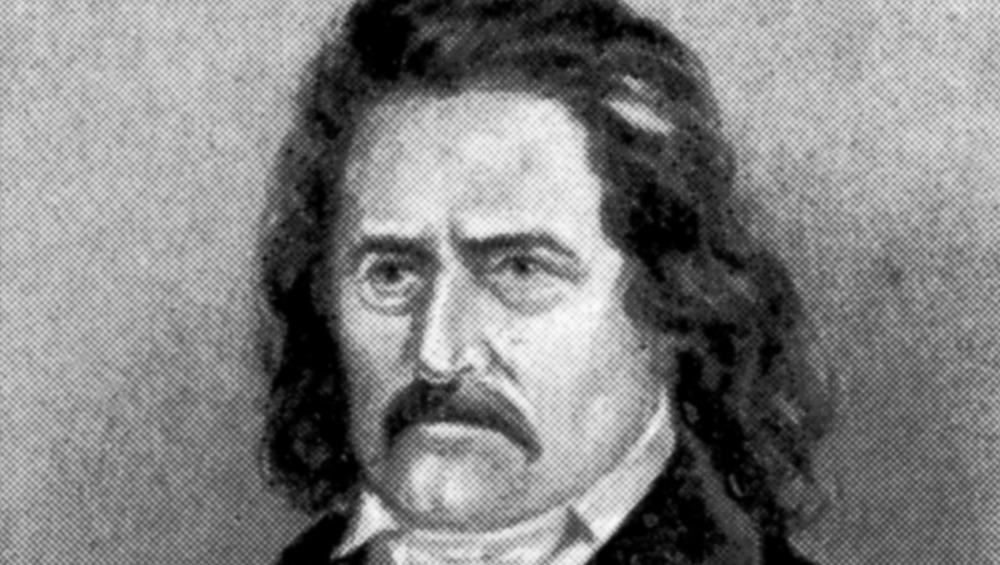

Howe, who worked in a Massachusetts machine shop as a young man, became fascinated by the idea of developing a sewing machine. "During this time it was suggested to him that the man who invented a machine that could sew would earn a fortune," according to Britannica. Howe became obsessed with creating such an appliance.

A long struggle, and then success

A school friend, George Fisher, not only gave him money for supplies and to support his family, but also offered him an attic workroom in his own home, according to Cambridge History. Most early sewing machines produced a chain stitch that tended to unravel. Howe's version featured a lock stitch created with two separate threads — a longer-lasting methodology.

The inventor would go through several versions of his machine. After the second one did not become profitable, Fisher decided to pull his financial support. Howe's brother, Amasa, tried selling his creation in London and found an interested corset producer, William Thomas, who purchased English rights to the invention and asked Howe to make a prototype specifically for corsets. Howe worked for him in London, before traveling to America to rejoin his family in 1848.

In America, Howe reunited with his sickly wife, who soon died. The inventor had so little money he needed to borrow the proper clothing for her funeral. Still, Howe continued experimenting on sewing machines. Others had also entered the field, including, per Bellatory, Isaac Singer (yes, of Singer sewing machines) and infringement suits started.

By 1854, the courts decided that Howe's patent was the first, and all machine makers needed to give him royalties for machines sold. By the time he died in 1867, Howe's estate was worth $13 million, reported Lost to Sight. Singer would go on to create an electric sewing machine for home use ... and, according to Encyclopedia.com, would leave his heirs about $13 million as well.