The Real Reason You Can't Find The 1890 U.S. Census

The U.S. census serves a number of purposes. Since the census counts how many people there are, and congressional representation is based on population, the census is used to determine how many Congresspeople each state gets, per CU Denver News, posted by the University of Colorado at Denver. The government also decides how to allocate federal funding based on the census, which affects things from public transportation and highways to firefighters. The U.S. Census Bureau writes that businesses use the census "to decide where to build factories, offices, and stores."

But beyond the contemporary functional application of the census, censuses can also offer a phenomenal glimpse into hundreds of millions of lives throughout history. At one point, anyone above the age of 10 had to list an occupation on the census, and My Heritage reports that this had some amusing results, such as 15-year-old Catherine Cudney, whose occupation was listed in 1880 as "does as she pleases," or 55-year-old James Coleman, who's listed as a "blow hard."

Not every census had the good fortune to survive the ravages of time, however, and as a result, sometimes all we know is what we have lost. Here's the real reason you can't find the 1890 U.S. Census.

What made the 1890 census different?

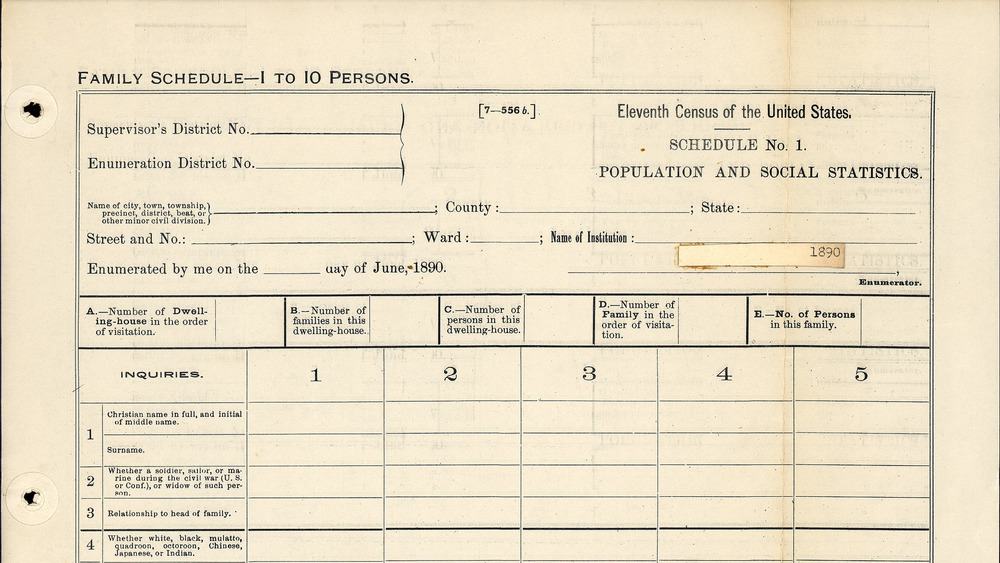

The official census date for the 1890 census was June 1, and the enumerators finished counting the census by July 1. According to The National Archives, the 1890 census differed in several ways from those that had preceded it: "The schedule contained expanded inquiries relating to race (white, black, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, Chinese, Japanese, or Indian), home ownership, ability to speak English, immigration, and naturalization."

This was also one of the first attempts to establish fecundity, which Science Direct defines as "the physiological maximum potential reproductive output of an individual (usually female)" over the course of a lifetime. Married women were asked how many total children had been born to them, in addition to how many were living at the time of the census. The U.S. Census Bureau notes that the 1890 census also included the first general questions on housing.

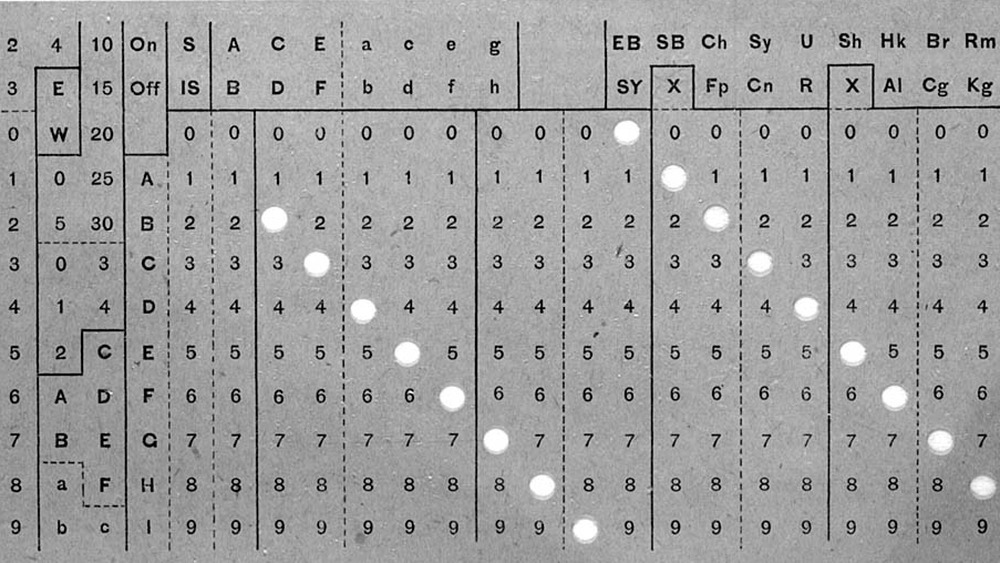

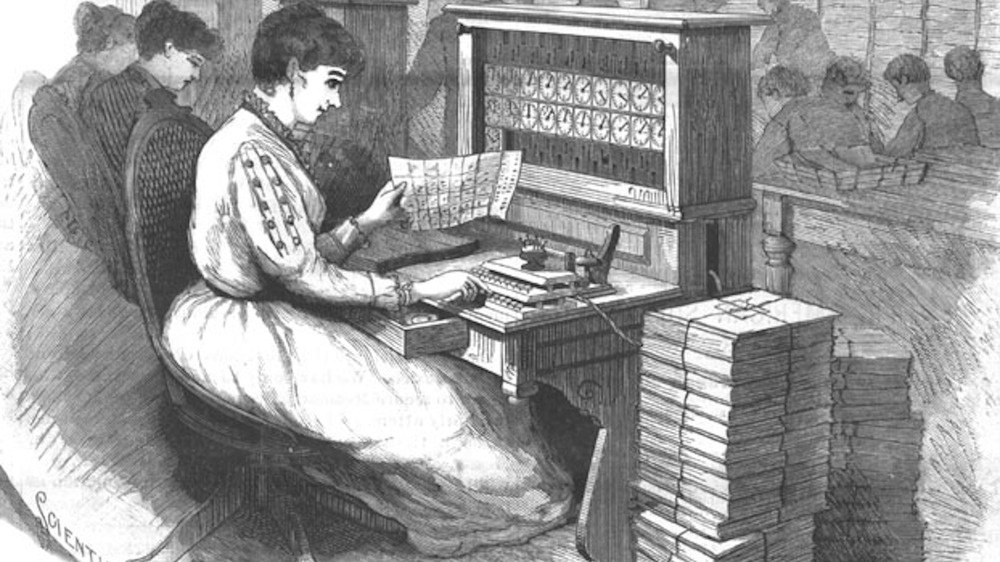

Fast Company writes that the 1890 census can be considered one of the starting points for computers, for there was a reason that the census was tallied so quickly. Before the 1890 census, compiling the census sometimes took almost eight years, as in the case of the 1880 census. But for the 1890 census, Herman Hollerith, an engineering student, came up with an idea to "translate data on handwritten census tally sheets to patterns of holes punched in cards."

New machines would be required to both punch and read the holes in the cards, but Hollerith's technology was taking off. "The company he founded would, after he retired, become International Business Machines — IBM."

Inconsistencies with the 1890 census

The 1890 census recorded the population of the United States as 62,979,766 people. According to The National Archives, however, there were complaints almost immediately about accuracy in general and undercounting in particular. In some instances, recounts were demanded.

American Heritage reports that the competition between St. Paul and Minneapolis was so great that Minneapolis was accused of deliberately inflating the city's population. St. Paul's census count was also found to have numerous discrepancies, although "there was no evidence of conspiracy, only of small-scale fraud and incompetence."

Despite 33 federal indictments against enumerators from both cities, almost everyone "walked away free."

According to Genealogy Branches, officials in New York City also believed that the census had given an inaccurate count of the citizens of the city. Another census was undertaken between September 19-October 14, 1890, "and was enumerated by New York City Policemen." During this count, 13 percent more people were found than those on the first 1890 census. In response, New York police were accused of "padding the census count," New York Public Library reports.

What happened to the 1890 census?

The census had been tallied, but before it was officially published, it was stored by the Department of the Interior in the basement of Marini's Hall in Washington D.C. And on March 22, 1896, the first tragedy struck. During the night, a watchman discovered that the back of the building was on fire. By the time firefighters arrived, "dense smoke [was] pouring from the basement," Newspapers.com writes.

Although the firefighters were able to put out the fire before sunrise, "the original 1890 special schedules for mortality, crime, pauperism and benevolence, special classes (e.g., deaf, dumb, blind, insane), and portions of the transportation and insurance schedules were badly damaged by fire," reports The National Archives.

The general population schedules were unharmed, since they were stored separately, in the Commerce Building's basement. But on January 10, 1921, an employee at that building saw smoke coming from the elevator shaft. By the time firefighters put out the fire, "archivists found 25 percent of the 1890 census schedules destroyed, while half of the rest sustained serious water damage."

There was debate over whether or not the records could be salvaged, but it's unclear exactly what happened between 1922 and 1932 to the census records. In December 1932, the 1890 damaged census records were included in a list of documents scheduled to be destroyed. In an ironic juxtaposition, "just one day before Congress authorized the destruction of these records, President Herbert Hoover laid the cornerstone for the new National Archives Building."

What's left of the 1890 census?

Although many people protested the destruction of the 1890 census, by 1935, the 1890 census papers were destroyed. The National Archives writes that in 1942, it was believed that only a damaged bundle of Illinois schedules had survived the purge.

But in 1953, the National Archives found fragments from "Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, and the District of Columbia." Overall, there are at least 6,000 names in the surviving 1890 population schedules.

Although New York City's police census wasn't used for congressional appointments, according to New York Family History, the majority of the 1890 Police Census survives to this day. Out of 1,008 books, 894 remain, all of which are available on microfilm and at the New York Public Library.

Fragments of the 1890 Special Enumeration of Union Veterans and Widows also survive, although "nearly all of these schedules for the states of Alabama through Kansas and approximately half of those for Kentucky appear to have been destroyed before transfer of the remaining schedules to the National Archives in 1943," according to The National Archives.