The Creepy History Of Sculptures Made From Human Corpses

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

For folks who want to get into the arts and pick up a new hobby, there's lots of options. Start with watercolors, maybe charcoals. Buy a pack of colored pencils. Crochet a cozy for your grandma's coffee cup, or graffiti up that mural on the abandoned building downtown. Or try something more avant-garde like sand art, or build a sugar art sculpture like an Elizabethan. There's even magnet art for the scientifically inclined. Heck: you can even try corpse art.

Wait: corpse art?? Yes, corpse art. To try corpse art, you don't have to be Dexter, or Hannibal Lecter, or a medieval Icelandic peasant who wore his neighbor's leg skin and empty scrotum as a set of "necropants." No, no. All you need is a bunch of flayed flesh — horses, people, whatever — like the collection of 18th-century taxidermist, pathologist, and anatomist Honoré Fragonard, one of the "first medical masters of France," as Atlas Obscura says, appointed by King Louis XV to Lyon's first veterinary school. And to be clear: "flayed" in this case indeed means skinless, so everything underneath — organs, sinew, bones — is exposed.

Fragonard, with his extreme, macabre predilections, was considered a "madman." He began by displaying the vivisected "flayed figures" of animals, or écorchés. Before long, while his peers were using wax, ceramic, and plaster to sculpt lifelike visions akin to Madame Tussaud's Beyoncé (really quite good, as you can see on Elle), Fragonard was elbow-deep in posing preserved flesh in dramatic, lifelike scenes.

Riding a trend of medical interest in cadavers and the human form

Fragonard, though, was merely riding a wave of scientific experimentation and artistic trends mounting since the 15th century. As Britannica tells us, écorchés were fairly common at the time of Fragonard, except they were more often illustrations, or un-posed cadavers made from wax. At a time when medicine sought to better understand the human body, dissections were common and often witnessed by artists who, to create records, drew what they saw. Emphasis was on realism.

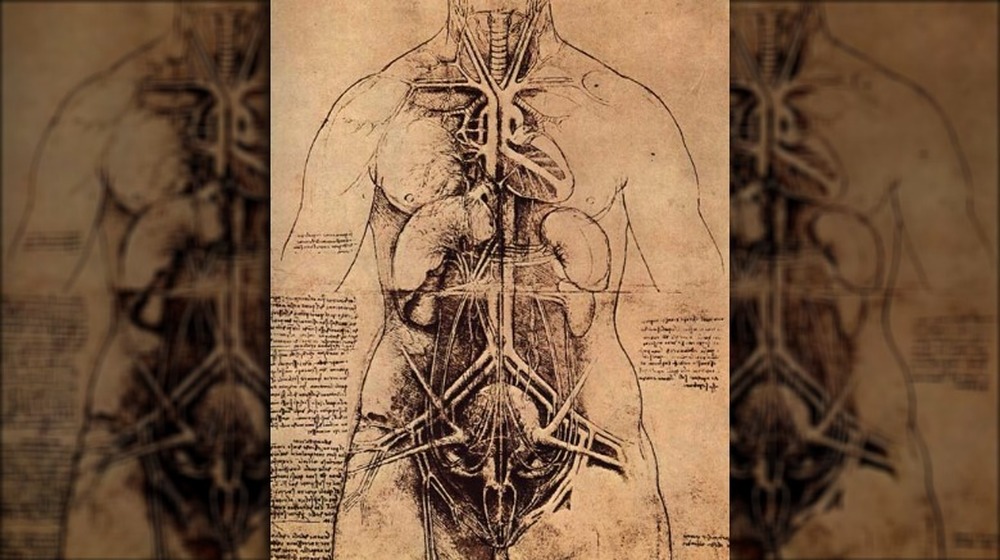

Take "Anatomical Venus" by Clemente Susini, a pretty, pale young woman with "seven anatomically correct layers," including a fetus, as The Guardian states, created from 1780 to 1782 to help medical students study before a time when cadavers could be easily preserved. Far before then, Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519 CE), per Britannica, dissected 30 corpses during his lifetime for the purposes of creating drawings. Famed Renaissance artist Michelangelo (1475 – 1564 CE) accepted a commission from the church based on quantities of corpses, and before then took to dissecting cadavers in Santa Maria del Santo Spirito in Florence from age 17, per Ranker, in order better understand the subjects of his art. Eighteenth century Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch and his daughter Rachel crafted scenes of "skeletal fetuses" and flowers, respectively, as Hyperallergic states.

The landmark medical textbook Gray's Anatomy, published in 1858, acts as a capstone to this period and contains highly detailed drawings still used by medical professionals today.

Anatomy as art transformed into modern-day mortuary techniques

As Hyperallergic says, the need for "anatomy as art" has since faded, as medical knowledge has reached a point where the need for new écorchés — either illustrative or sculpted — isn't very necessary. It stands to reason that only certain people, now the same as then, might be able to stomach exposure to corpse sculptures: folks drawn to the macabre, or those drawn to surgical work, or mortuary careers. After all, who else is going to groom a loved one for a wake or internment in a coffin besides morticians: people whose knowledge of preserving and caring for the dead builds on centuries worth of anatomical knowledge and embalming techniques?

Admittedly, someone like Fragonard went beyond medical need into "anatomy as art." Twenty-one of his 700 works remain, including "The Man with the Mandible," a valiantly-posed corpse depicting the Biblical story of Samson killing a bunch of "Philistines" with a donkey jaw, and "Horseman of the Apocalypse," a flayed man riding a flayed steed based on Albrecht Dürer's painting derived from the Biblical story of the apocalypse (you can get a peek on the Musée Fragonard at the École Nationale Vétérinaire de Maisons-Alfort website).

Sixteenth century Flemish doctor Andreas Vesalius summed it up thusly: "Anatomy... embraces the study of man and must properly be regarded as the prime foundation of the whole art of medicine." Note that medicine itself was considered an "art."