The Messed Up True Story Behind Klansman Asa Earl Carter's Giant Hoax

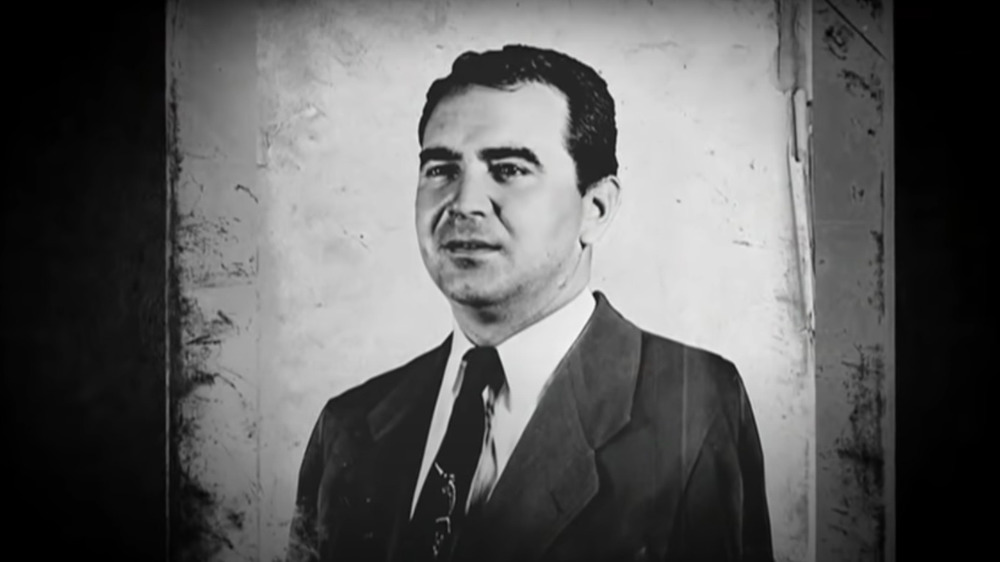

Asa Earl Carter was a white American man who spent the entirety of his life as a racist person, repeatedly going on tirades against Black people and Jewish people. But for the second half of his life, he also adopted an identity that involved pretending he was half-Cherokee and writing romanticized stories about his "heritage."

Calling himself "Forrest Carter," one of his books, The Education of Little Tree, became incredibly popular after Carter's death. And despite the fact that Carter was remarkably bad at keeping up his deception, his faux identity wasn't accepted as a hoax until the 1990s.

Asa Earl Carter is one of many in the United States who has pretended to have Native ancestry. Miguel Douglas writes that "many Americans who wish to be Native American only do so due to the benefits they believe Native Americans receive [... and] for many claiming Native ancestry, there is no genuine attempt to learn more about the cultural, spiritual, or traditional practices that accompany that ancestry—merely saying they are part Native is sufficient enough to them." At the end of the day, the fact that this hoax persisted for so long has more to do with white people's willingness and desire to believe it rather than the lack of evidence against a racist man. This is the messed up true story behind Klansman Asa Earl Carter's giant hoax.

Who was Asa Earl Carter?

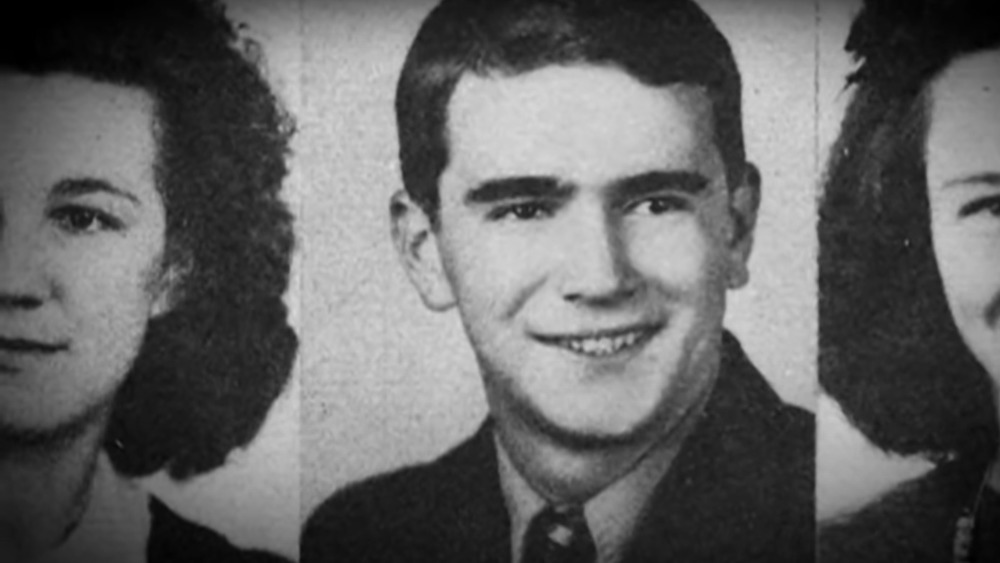

Born on September 4th, 1925 in Anniston, Alabama, Asa Earl Carter was one of five children born to Ralph Carter and Hermione Weatherly Carter. Growing up in the city of Oxford, Carter would later claim that he was orphaned when in actuality, his parents were very much part of his life.

Texas Monthly reports that Carter was descended from Confederates on both sides and throughout his childhood was fascinated by the stories about them. After graduating high school in 1943, Carter joined the Navy during World War II, although he repeatedly questioned, "Why should the United States be fighting a Jewish war?" He reportedly even told his friends that he deliberately joined the Navy so he wouldn't be forced to confront German soldiers, "whom he regarded as racially akin to his true ancestors, the Scotch Irish."

In 1945, Carter left the Navy and after marrying Thelma India Walker, his high school girlfriend, they moved to Colorado. After spending a few years in Colorado working at a radio station and studying journalism, Carter moved back to Birmingham, Alabama around 1953 or 1954. According to the Birmingham Public Library, once back in Alabama, Asa Earl Carter caught the eye of the American States Rights Association. They hired Carter to go on the WILD radio station and advocate against integration, but Carter was a little too bigoted, even for the American States Right Association. Within six months, he was fired for his antisemitism.

Asa Earl Carter's own Klan

Upon moving to Birmingham, Carter joined the Ku Klux Klan, but he felt that wasn't enough. According to All That's Interesting, he also started his own "paramilitary unit of 100 men [called] 'The Original Ku Klux Klan of the Confederacy.'" And for those who considered such overt racism comparatively gauche, Cart also started a "white citizens council," which was considered a "respectable segregationist alternative" to the KKK, Texas Monthly writes. And although Carter denied being a member of the KKK, his paramilitary gang was clearly incorporated into the KKK and "his signature appears on the articles of incorporation."

Membership in these white citizens councils especially rose after the Montgomery bus boycott started in the end of 1955, and at one point the group that Carter had founded "claimed 30 to 40 chapters." The Original KKK of the Confederacy was also responsible for the assault of Nat King Cole. In 1957, the group also castrated a Black man chosen "at random in a Birmingham suburb", although Carter reportedly wasn't present at this event.

As with the radio show, Carter's antisemitism got him in trouble with the other racists. He refused to allow Jewish people to join, and within a couple of years, Carter was pushed out of the white citizens council movement.

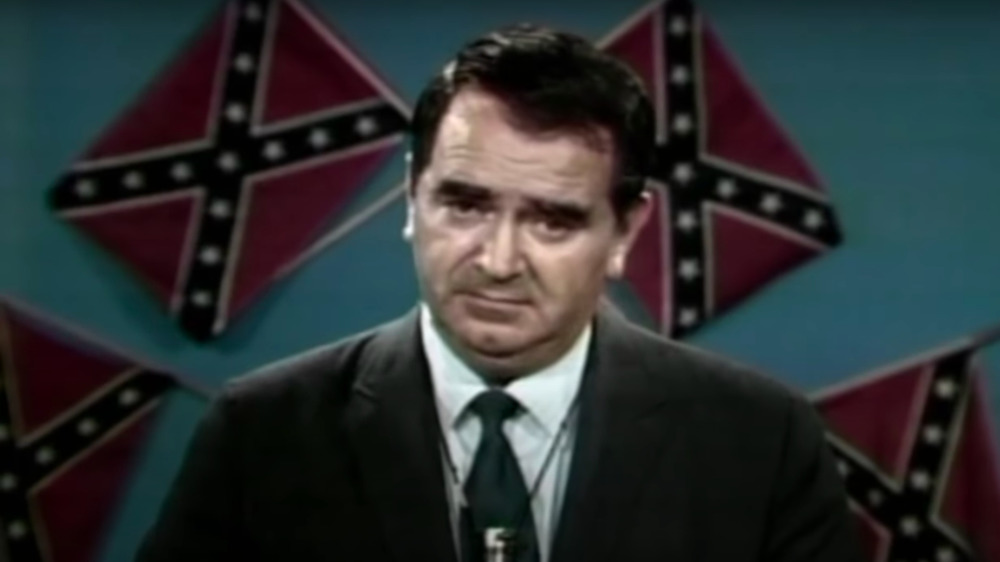

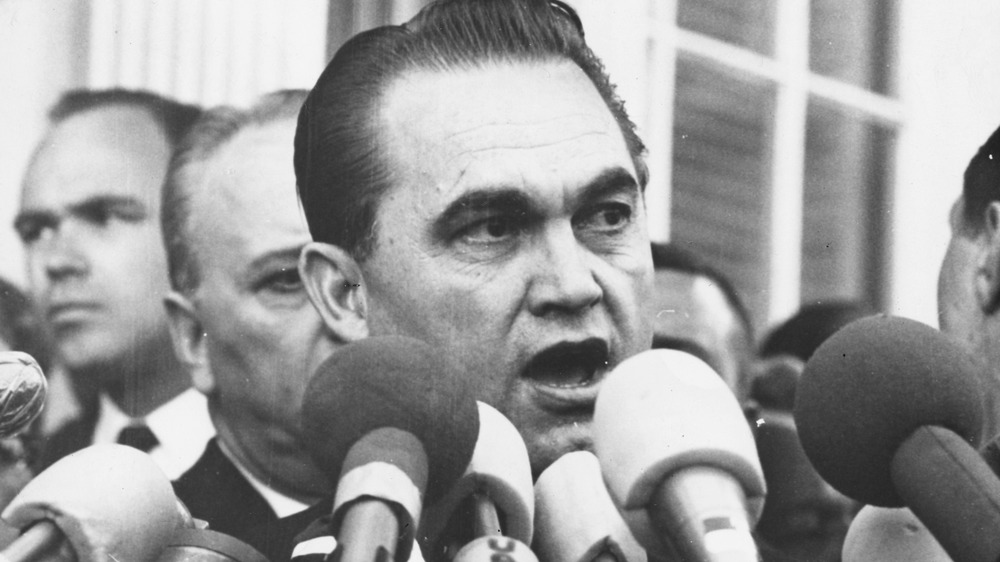

Asa Earl Carter was George Wallace's speechwriter

After being kicked out of the white citizens council movement, Asa Earl Carter made a run for state lieutenant governor in 1958, but he placed last. Texas Monthly writes that in response, he called Klan leadership "a bunch of trash" in a newspaper article. This caught the attention of George Wallace, who was running for governor of Alabama against John Patterson, who was supported by the KKK. Wallace recruited Carter to join his team as a speechwriter, although he ended up losing his first gubernatorial run. According to Politico, after his defeat, Wallace decided to adopt a more segregationist approach, believing that the endorsement from the NAACP had been his downfall.

However even for the newly-segregationist Wallace, "Carter's sinister reputation presented a problem," so the Wallace campaign decided to hide Carter out of the public eye, putting him in the farthest and most tucked away offices. Wallace would later even deny "any association or collaboration" with Carter, so it's unclear if Wallace's aides hid Carter's existence from Wallace entirely. Meanwhile, Carter wrote the famous words from Wallace's 1963 inaugural address, "Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!"

But when Wallace started to tone down his racist rhetoric in preparation for a presidential run, Carter was incensed. He even tried running against Wallace for the governor's seat after Wallace's presidential run was unsuccessful, but once again Carter was in last place. During Wallace's 1971 inauguration, Carter protested with signs that read "Free Our White Children."

Asa Earl Carter's racist logic

Asa Earl Carter was incredibly open about his white supremacist ideas. All That's Interesting writes that Carter was described as a "segregation leader" by the New York Times, and he even complained to the press in 1956 about how the NAACP was using rock and roll music "to 'infiltrate' Southern white teenage culture."

According to Texas Monthly, Carter also attributed the NAACP to be "a concoction of world Jewry," and blamed Jewish people for the rise of the civil rights movement. Carter also believed that Black people were "undeserving compared with the patient and brave Indians, who had suffered terrible wrongs inflicted by the Yankees." A friend of Carter's from childhood, Buddy Barnett, claimed that Carter often spoke about how Black people "don't know what it is to be mistreated," asserting instead that "the Indians have suffered more."

Carter also repeatedly advocated for violence during his own speeches, at one point claiming that if the federal government insisted on pushing integration, "If it's violence they want, it's violence they will get." At one point Carter said he was willing to put "blood on the ground" to put a stop to integration.

Asa Earl Carter's reinvention as Forrest Carter

Asa Earl Carter was devastated by George Wallace's victory. According to NPR, after Wallace's 1971 inauguration, Alabama reporter Wayne Greenhaw approached Carter and Carter started to cry, saying that "Wallace had sold out to the liberals." Greenhaw claims that this was the last time he saw Carter: "It's like he just vanished, dropped off the face of the earth." Carter also called a close friend, Ron Taylor, to tell him that he was "going away."

However, according to Texas Monthly, Carter didn't drop out of sight immediately. In 1971, he set up another paramilitary organization, "whose members wore gray armbands with Confederate flags." It wasn't a success, and seemed only to further demoralize Carter, who was arrested three times on alcohol-related charges the subsequent year. This seemed to be the final straw.

Carter's reinvention and move to the Southeast wasn't unique, "but where others moved to find a new future, Asa Carter moved to find a past." In 1973, Carter and his wife moved to Florida and he fully became Forrest Carter, incorporating the name of Nathan Bedford Forrest, founder of the KKK and Confederate soldier. Carter set his sons up in Abilene, Texas, and visited often, but referred to them as his nephews. "Forrest" Carter started to create a new past for himself. He told people he was part Cherokee and a former cowboy who "spent his time drifting around the country from his home in Florida, where his wife lived, to the Indian nation, where his kinfolk lived."

The hoax that was Forrest Carter

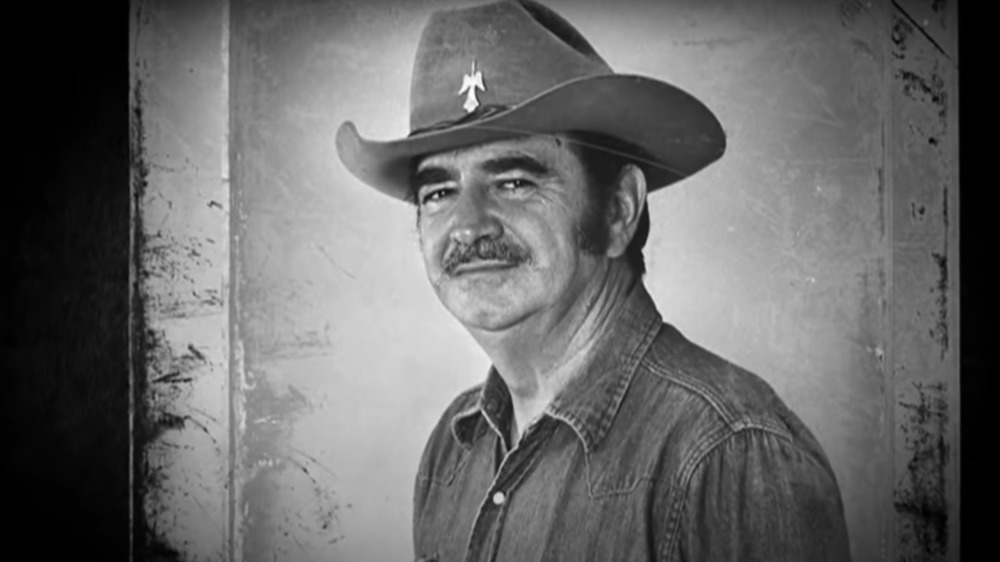

Everything about Forrest Carter became a performance. Boasting that he had experience as a dishwasher, a bronc rider, and a ranch hand, Carter also claimed that he could write without any formal education. Texas Monthly writes that "everything about the way he presented himself was a fraud."

Dressing with a black cowboy hat and a bolo tie with a turquoise stone, he told tall tales and sang songs to his Abilene friends. "Sometimes, especially if he had been drinking, he would perform Indian war dances and chant in what he said was the Cherokee language." And according to NPR, many people were charmed by Carter. Chuck Weeth, who met Carter in 1975, claimed that "I liked him from the start."

At one point, Carter spoke to a literature class at Hardin-Simmons University. Adopting what he fantasized to be the mentality of an indigenous person, he told a story about looking for work and how, despite the fact that he was starving to death, he refused a meal from the owner of the ranch because he "wouldn't take it without working first." Carter also claimed that afterwards he became close friends with the rancher, Don Josey. However, although it's true that Carter and Don Josey were friends, every other part of that story is completely fabricated. They'd actually met at a rally for Lurleen Wallace, for whom Carter also wrote speeches during her ultimately successful gubernatorial run in 1966, according to Birmingham Public Library.

Forrest Carter's rising fame

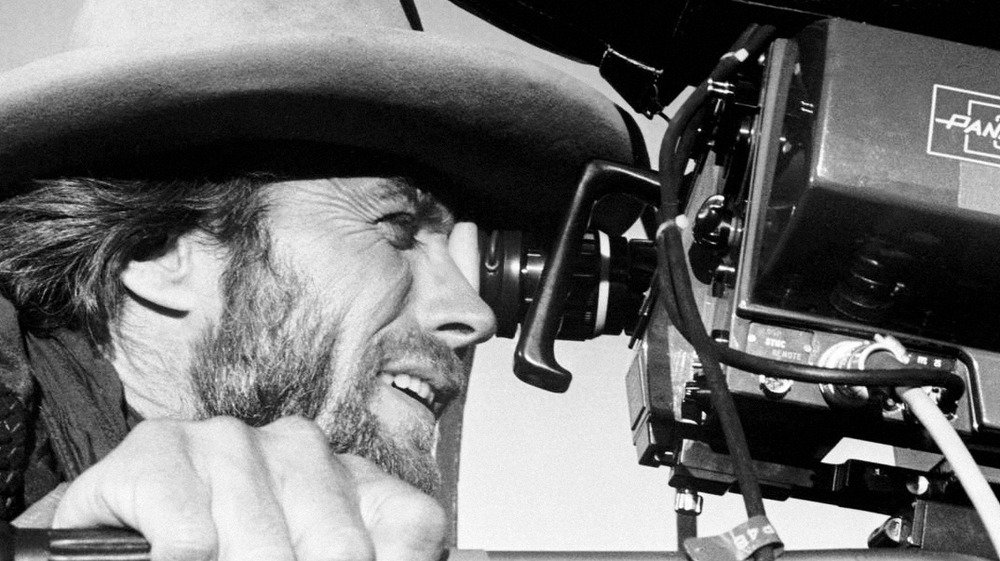

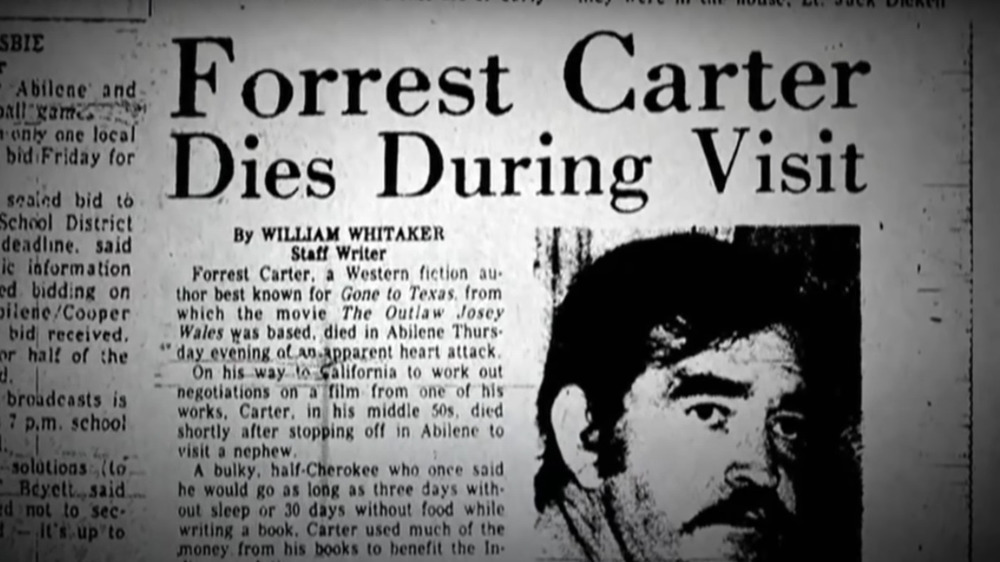

Asa Earl Carter appears to have tried out his new name for the first time 1972. "Forrest" Carter's first novel, The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales, later renamed Gone to Texas, was first published that year. It was relatively successful, although its biggest claim to fame is that in 1976, Clint Eastwood adapted the novel into the movie The Outlaw Josey Wales. According to NPR, Carter published a total of four books, one of which was meant to be an autobiographical story about "Carter's childhood with his Cherokee grandparents."

In 1975, Carter ended up on The Today Show, being interviewed by Barbara Walters. Carter wore his cowboy hat throughout the interview, and noticeably looked down at all times, "he never would face the camera." During the interview, Carter claimed that he worked wrangling horses and that "he was the storyteller to the Cherokee Nation" during his time in Oklahoma. According to Texas Monthly, Carter had been worried that he was going to be recognized, so he showed up to the interview tanned, 40 pounds lighter, and with a mustache. Meanwhile, Carter's old friend Thomas saw the interview and fell onto the floor laughing: "Asa's on TV! He had pulled it. He had fooled them."

Wayne Greenhaw also saw the interview, and he was "bumfuzzled," in his own words. And when he started looking into what this new Carter was up to, Carter got in touch with Greenhaw and said, "You don't want to hurt old Forrest, do you now?"

Wayne Greenhaw's article on Asa Earl/Forrest Carter

Wayne Greenhaw retorted with, "Come off of it Asa, I recognize that voice," and in 1976, Greenshaw published an article in the New York Times identifying Forrest Carter as Asa Earl Carter. Headlined "Is Forrest Carter really Asa Carter? Only Josey Wales may know for sure," AP News reports that the article "quoted several people who knew Asa as saying he was Forrest." Jack Snows, chief investigator in the Alabama Attorney General's office, recognized Carter during his appearance on The Today Show.

The Washington Post writes that Carter and his editor at Delacorte Press, Eleanor Friede, both denied the charges. But Carter didn't even try that hard to hide his true identity. The copyright application for his first book even used the same address he had in Alabama in 1970.

Greenhaw thought that the article was going to be the start of unearthing a scandal in 1976, not 20 years later. Instead, "a curious thing happened after the article came out, something that surprised Wayne Greenhaw. And it probably surprised Asa and Forrest Carter. What happened was nothing," per This American Life. That same year, just a few months after the article came out, Delacorte Press published Carter's "autobiography," The Education of Little Tree.

'The Education of Little Tree'

When The Education of Little Tree came out, it wasn't a success, but it wasn't quite a failure either. Texas Monthly describes The Education of Little Tree as selling "moderately well," while the Washington Post claims that its sales were poor.

Either way, the book was soon out of print and Asa Earl/Forrest Carter died in 1979. However, in the "wave of rising interest in all things Native American," according to This American Life, The Education of Little Tree was reissued in 1986 by University of New Mexico Press. The reissue came with a forward written by "an actual Cherokee writer who called the book deeply poignant and compared it to Huck Finn."

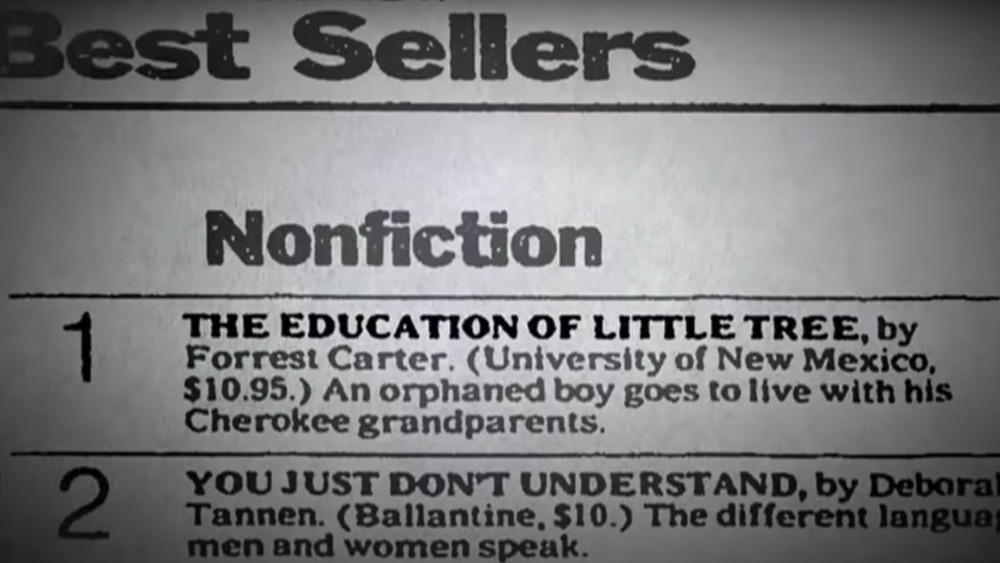

This time around, the book sold over one million copies, reaching number one on the New York Times Nonfiction Best Seller List in 1991. And in 1994, it got another big boost when Oprah Winfrey recommended it on her show, later adding it to her website's list of recommended books as well.

Denying until his death

Although few people were trying to poke holes in his performance after the New York Times article, Forrest Carter still had trouble keeping up his façade. According to Texas Monthly, more than once, Carter erupted into a racist tirade about Black people, at one point getting so loud that "other diners began to glare."

In a letter to Don Josey, Carter at one point revealed plans for a sequel to The Education of Little Tree, in which he was planning on including "some good stuff in there about knocking on your back door for work and eats, etc. in the process of which we will try to learn them sick New Yorkers something." But by 1979, the drinking had caught up with him and many of his friends were worried that he'd never sober up enough to write another book.

And on June 8th, 1979, Carter died at his son's house, ostensibly due to a drunken fist fight, according to All That's Interesting. The cause of death was listed as "aspiration of food and clotted blood" due to a fight, and the ambulance driver reportedly claimed that Carter had likely choked on his own vomit when he fell. According to NPR, Carter was buried in Alabama, "where today his tombstone still reads, 'Asa Earl Carter.'"

The innumerable inaccuracies of 'Little Tree'

Other than being an outright lie, The Education of Little Tree is riddled with inaccuracies. According to NPR, the Cherokee words that Forrest Carter included in the book weren't even from the actual Cherokee language: "They were just made up." The clothes that Little Tree is described as wearing also have no basis in actual Cherokee clothing.

Texas Monthly writes that Carter's "description of the Cherokee way of life is romanticized, like something out of Longfellow." Dr. Richard L. Allen, policy analyst for the Cherokee Nation, describes it as the "magical mystical idea of American Indian people."

In the book, Little Tree has an ability to communicate with trees and he could also "talk to the stars," something which no Cherokee has been known to do. And throughout his book, Carter repeatedly projects his own fantastical imagining onto the narrative of Native people in the United States. Even the expression "Mon-o-lah, the earth mother" used in the book has no basis in reality. But in the end, Carter wasn't concerned with reality. His romanticization was built on the same dehumanization as his racism.

Denounced as a hoax

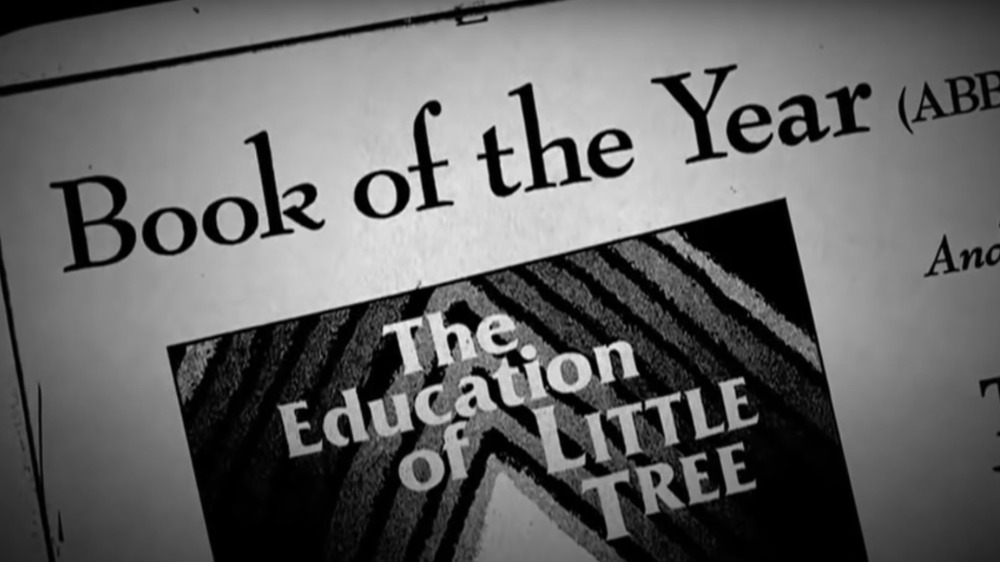

The Education of Little Tree continued to benefit from public acclaim and in 1991 even won the very first ever American Booksellers Book of the Year award. But soon after, Professor Dan T. Carter (no relation) wrote an op-ed in the New York Times deriding the book as a hoax. In a phone interview to the Washington Post, Professor Carter stated, "There's no question who this guy really was. The new age guru was a gun-toting racist, and this book is a hoax."

Eleanor Friede, Forrest Carter's editor, once more defended the author, claiming that the controversy was "a family mix-up," and Rennard Strickland, who wrote the forward "stood by" the book. But according to All That's Interesting, after the article came out in the New York Times, Asa Earl Carter's widow Thelma admitted that "Forrest" Carter was a fraud.

According to Texas Monthly, once Thelma acknowledged the hoax, the New York Times moved The Education of Little Tree from the nonfiction list to fiction. And in 1994, even Oprah Winfrey eventually took it off her book list and acknowledged the book's controversy on her show. However, the book remained as a recommendation on her website until 2007, although this was blamed on an "archival error," according to the Los Angeles Times.