The Crazy Real-Life Story Of Miguel De Cervantes

Ah, yes, Don Quixote. That one story where the old man goes and fights a windmill, right? That's the one? The whole windmill scene is probably one of the most famous things that came out of the novel, or at the very least, it's the one thing that people know even if they didn't end up reading it in high school English class. But just that fact — that it's one of those novels that gets used as assigned readings for classes — paints its author, Miguel de Cervantes, as a literary giant.

And, credit where credit is due, he kind of is. Don Quixote was the start of a new kind of literature, one with a format more like that of TV shows than it might initially seem. It helped pave the way for modern fiction and story-telling, and Cervantes is a big part of that.

But that doesn't mean he was some pampered academic, or a pseudo-Renaissance noble with all the time and money to write whatever he pleased. He wasn't a genius who instantly found success, either. Frankly, his entire life was a pretty wild adventure from start to finish, marked more often with failure, legal issues, and debt rather than fame, fortune, and success.

Miguel de Cervantes came from money (kind of)

On paper, it would seem like Miguel de Cervantes was born into money, part of a wealthy and well-off family. As explained by Donald P. McCrory in his book, No Ordinary Man: The Life and Times of Miguel de Cervantes, Miguel de Cervantes' grandfather — Juan de Cervantes — was actually a successful lawyer. He'd built up a considerable fortune for his family, allowing them to live a comfortable lifestyle among the upper class.

But all wasn't well. For a number of reasons, he up and left, taking his oldest son with him, leaving Rodrigo de Cervantes — Miguel de Cervantes' father — as the sole breadwinner of the house. And that didn't turn out especially well. Rodrigo was used to the comfortable lifestyle of a noble house, filled with leisure, which would've blown through any remaining money pretty quickly. Without a formal university education, his prospects weren't great either, and he could only find work as a surgeon (which, at the time, was more like a barber who also tended to minor wounds, but was mostly regarded as a fraud).

Marriage didn't help him either, with his wife's family refusing to help. By the time Rodrigo had a family of his own, he was constantly on the move, unsuccessfully chasing work or escaping the threat of debtors' prison. Miguel de Cervantes' mother, Leonor de Cortinas, did what she could to help, too, but by all means, money was tight.

Miguel de Cervantes' childhood was all over the place

With Cervantes' father, Rodrigo de Cervantes, finding only occasional work as a less-than-successful surgeon, the family moved around. A lot. Cervantes was born in Alcalá de Henares in late September 1547, but he wasn't there for all that long. Author Donald McCrory explains that there was a lot of competition for work as a surgeon in the area, so Rodrigo moved his family to Valladolid, hoping that it might bring more opportunity.

That didn't end up being true. Things actually went the opposite way, and Rodrigo ended up in debtors' prison for some time. On the heels of that, it's guessed that the family ended up migrating around the rural countryside for a while, but there's not a whole lot of information on where exactly they ended up at any given time.

Still short on money, the family eventually moved to the region of Andalusia, for help from Cervantes' grandfather, Juan de Cervantes. They did get that aid, Rodrigo finding a different job (likely with his father's help). But that didn't last long, either. Juan died in 1556, kicking off another seven year period where no one knows for sure where the Cervantes family ended up. Best guess? They might've gone to Cabra, the city where Rodrigo's brother was mayor, potentially heading there in 1558. But the next definite mention of the Cervantes family was in Seville in 1564, though they moved to Madrid in 1566. It's a lot of moving, to say the least.

It's hard to say what Miguel de Cervantes' education looked like

With Rodrigo de Cervantes moving his family around based on his ever-changing financial (and legal) troubles, his son's education is something of a mystery, though Author Donald McCrory offers potential answers. Miguel de Cervantes probably started his schooling around age 6, studying under a family friend — Alonso de Vieras — while the family was in Córdoba. After a year, he probably attended the local college, where students learned mostly by listening instead of reading.

After that, though, it's sort of hazy. While the family was on the move, some biographers think that Miguel was entirely self-taught, devouring books. McCrory doesn't agree, insisting that a young boy would've needed some amount of direction, and that Cervantes must have had some kind of schooling.

What does seem likely, though, is that Cervantes was enrolled in the Jesuit school in Seville, says Britannica. It was expanding around the time the family was there, and would've cultivated a love of arts and literature in the young Miguel. Again, it's hard to know. A growing Jesuit school would've cost money that Rodrigo might not have had, but his lack of formal education might've made him ensure better for his son.

Once they moved to Madrid, Miguel was taught by Juan López de Hoyos, the royal chronicler who recorded the events of Queen Elizabeth of Valois' funeral. It was under his tutelage that Cervantes' first works were published — poems included in the book about the Queen's death.

Miguel de Cervantes worked at the Vatican to avoid legal trouble

Despite the early writing success that Cervantes found in Madrid, he didn't stay in the city long. Barbara Keevil Parker and Duane F. Parker's Miguel de Cervantes mentions a royal warrant put out on Sept. 15, 1569, calling for his arrest, on account of him wounding the master mason Antonio de Sigura in a duel. The consequences would've included ten years of exile, on top of his hand being chopped off at the wrist. Ouch.

Technically, it's not proven that the warrant was for him (it just seems really likely), but either way, he ended up leaving for Italy when he was 21. And it seemed he had some idea what he was doing. Julio Acquaviva was in Madrid in 1568, intending to discuss matters of land ownership with the king, who wasn't really in the mood for talking, considering the recent death of the queen. Acquaviva would've had some extra time on his hands, during which he could've met Cervantes, potentially offering him a job as his chamberlain in Rome.

Cervantes ended up taking that job, attaching himself to Acquaviva and starting his job at the Vatican in early 1570, says Britannica, (Acquaviva himself would get promoted to cardinal a few months later). It's not known exactly what Cervantes did in that position. He might've taken care of Acquaviva's quarters, or maybe he acted as a secretary.

Miguel de Cervantes served in the military

A little while after Miguel de Cervantes started working in the Vatican, conflict ended up arising between Europe and the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans were starting to impose on Eastern Europe, which threatened their ways of life (religion also played into this animosity a bit, though). In Cervantes: Novelist, Poet, and Playwright, Don Nardo explains that Cervantes agreed with this view and was ready to join the army. His chance came in mid-1570 when the Turks invaded Cyprus, Cervantes answering the call to fight as part of the Holy League in 1571. By September of that year, Cervantes was serving on board the Marquesa.

All the same, he ended up winning renown during his service, with the most famous story happening during a battle near Lepanto. Sick with a fever and told he didn't have to fight, he still chose to, saying he'd rather serve his people and die than hide below deck.

Cervantes was put in charge of a group of 12 men due to his courage, and the battle began, raging around him. Somewhere amid all the chaos, Cervantes was shot — twice in the chest and once in his left hand. But that didn't stop him. He got back up and kept fighting. By the time the dust cleared, he'd helped bring victory to the Holy League. In the long term, Cervantes lost the use of his left hand but wore his wound with pride for the rest of his life.

Miguel de Cervantes was captured by the Barbary pirates

After fighting against the Ottoman Empire, Miguel de Cervantes was ready to return to Spain, bearing letters of commendation he'd earned due to his courage. In September 1575, he set sail for home alongside his brother (via Britannica). But they didn't quite get there — or, at least, not right away.

During the voyage, the ship the Cervantes brothers were on was attacked by the Barbary Pirates, and they were whisked off to Algiers, then a major center of slave traffic. They were held for ransom, effectively slaves, but Cervantes' letters caught his captors' eyes. As far as they could tell, he was a person of importance, and they treated him as such. Which meant that his ransom price was raised, though he was also treated with relative leniency (convenient, given he was known for his leadership among the captives).

He was trapped there for years, with his brother being freed three years earlier than him. But, eventually, his ransom was scraped together by his family in 1580, and just in time, narrowly avoiding being shipped to Constantinople with the other unsold slaves.

Ultimately, the experience was more than just a fleeting event for him. Later scholars like María Antonia Garcés note the lasting impression it must have left, coloring more than a few of his works with themes of captivity and bondage, images of slaves and suffering.

Miguel de Cervantes couldn't find fulfilling work

Fresh from war (and some traumatic life experiences) and armed with letters of commendation from notable military figures, Miguel de Cervantes was ready to find his way and take the world by storm. But things wouldn't go that way. In the eyes of the world, he was mostly just poor and unemployed.

Upon arriving in Spain, he tried multiple times for new posts in the New World, only to be turned down. The best he could get was being a royal messenger to Algeria (via Britannica). Eventually, he acquired rather thankless jobs as a civil servant. For a while, he acted as a commissary for the Spanish Armada, keeping records and providing goods to them from small rural towns. It wasn't great, but it paid the bills.

With the fall of the Spanish Armada, Cervantes was out of work. He tried again for a post in the Americas, only to be rejected, and spent time as a tax collector in Madrid. His time in these civil service positions distinguished him as surprisingly honest and trustworthy (a rarity for people in that line of work, according to Donald McCrory), but the jobs were far from rewarding, only barely taking care of his finances, and occasionally brought him into conflict with various authorities. It just wasn't what he was good at.

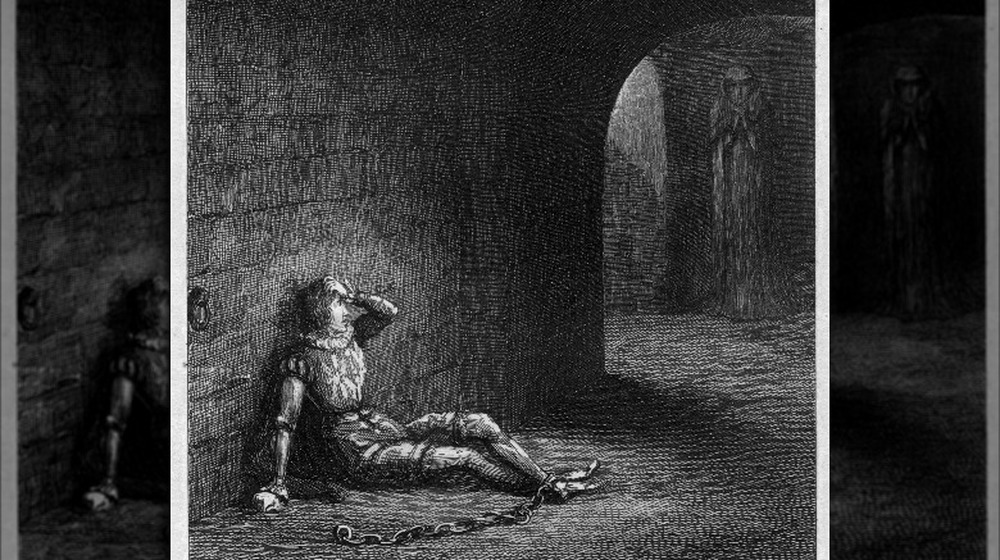

Miguel de Cervantes spent time in jail

The time Miguel de Cervantes spent as a civil servant surely wasn't great, but maybe the best example of that was the fact that he actually ended up in prison, and more than once.

In general, as a commissary, he wasn't exactly the best at keeping track of finances, and there were more than a couple times when discrepancies got him in trouble with his superiors (via Britannica). But his mistakes on this front really came to a head during his time as a tax collector. In 1597, discrepancies were found in three of his accounts, bringing him face to face with a judge. He was told he had to pay a sum of money as a result of those mistakes, but given his means, he had no way to actually produce that much money, as told by Barbara Parker and Duane Parker. Because of that, he was sentenced to seven months in the Crown Jail of Sevilla.

And then, just to make things even better, he couldn't avoid jail entirely even after his days as a civil servant were behind him. In 1605, someone was stabbed outside of his home in Valladolid, and everyone in the household was arrested (all of that amidst other litigation and legal problems at the time).

Miguel de Cervantes kept trying his hand at writing

Despite everything seeming to go wrong at every twist and turn — between slavery, unemployment, and jail time — Miguel de Cervantes continued to try to make his mark in the world of literature, albeit with varying success.

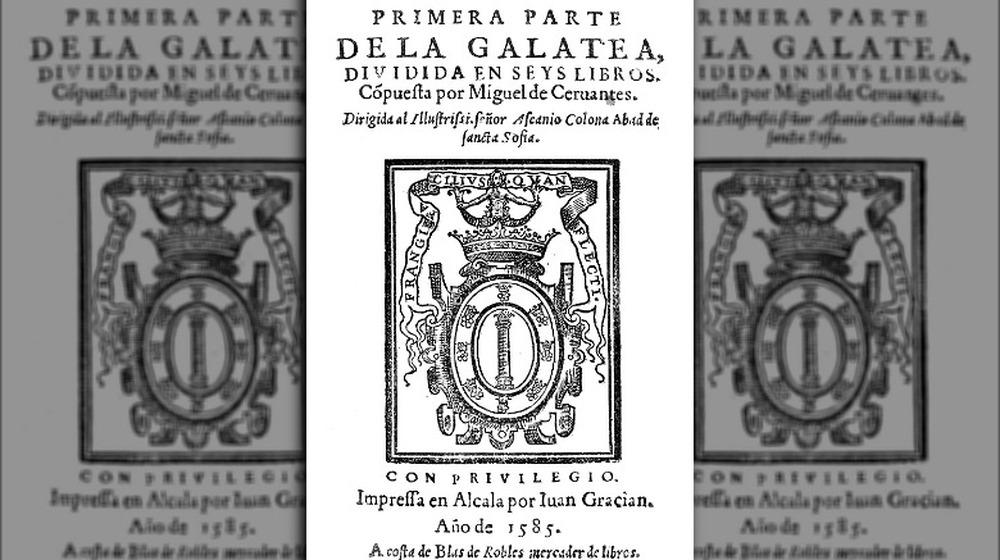

It wasn't like he was completely unsuccessful. Aside from his early poetry published while still a student, Cervantes did manage to win a different poetry competition in 1595, and even long before that, he did have fiction published as well (via Britannica). The main one that earned Cervantes acclaim was a pastoral romance titled La Galatea, which was the first to really make his name known to a wider audience. It did decently well at the time, but it wasn't really the start of something, exactly. Written in the mid-1580s, it was something of an outlier.

His attempts at writing for the theater were received with lukewarm acclaim, at best, and the introduction to The Portable Cervantes mentions that there were, supposedly, 20 or 30 plays he wrote in a short span of time, most all of which were un-actable. A little while later, he signed a contract to write six plays for a patron, only for the contract to fall through (it would've only paid him about $30 total anyway). And he even wrote some other stories, meant to be a part of a compilation...which was never published.

Don Quixote finally marked success for Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes didn't end up being a successful writer until pretty near the end of his life, but he did get there all the same. In the summer of 1604, he sold the rights to Part I of El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha, more widely known now as Don Quixote, to Francisco de Robles, getting the license to publish in September that same year (via Britannica). The book came out in January 1605 and was an instant success.

In The Man Who Invented Fiction, William Egginton paints a picture of what people at the time would've been treated to — a rowdy and raucous bunch, probably a few drinks into the evening, gathering around to hear the ridiculous tale of Don Quixote. They could laugh and make fun of Quixote, finding a good time in hearing about his exploits (which, yes, includes fighting a windmill).

But at its heart, Don Quixote ends up being more than just a bit of satire about a mad man trying to be a knight, at least historically. It's seen as one of the first works of modern fiction, pulling its audience into a fake reality filled with fake people but making that audience feel real emotions, all because the characters feel so lifelike. It's a lot like how people talk about fiction now. So even though Cervantes didn't actually see much profit from Don Quixote (at least, from Part I), his legacy lives on even longer.

There was a fake Part II to Don Quixote

Part II of Don Quixote wasn't published immediately after Part I. Even ten years after selling Part I, Miguel de Cervantes hadn't released Part II, and that long span of time, mixed with the wide reach of the book, ended up opening it up to criticisms. Some of which were pretty creatively delivered.

In September 1614, a Part II of Don Quixote was released to the public, but not one written by Cervantes (via Britannica). Instead, it was published in Tarragona by Alonso Fernandez de Avellaneda, who admired one of Cervantes' contemporaries. Apparently, it wasn't actually too badly written, if a little crude, compared to the real version, but it seemed it was written in order to insult Cervantes. Of course, Cervantes caught wind of this, and he didn't let this fake go unnoticed. So what did he do? He made reference to it in the real Part II, talking about and criticizing a fake Sancho and Quixote, making a not-so-veiled jab at Avellaneda. And given that people can and have still read that retaliation centuries after Cervantes' death, it was a pretty good means of getting revenge.