The Truth About Wild West Bank Robberies

The first truth about bank robberies in the Wild West is that although they are popular fodder for western movies, there really weren't that many in the early days. Bloggers J. Wisniewski and Kevin Nakamura submit that during the true Wild West era (which the Library of Congress defines as the years between 1865 and 1900), "only about eight true bank heists" took place across 15 western states. Towns were smaller back then they say, and buildings were crowded closer together to the extent that it was difficult to rob any business without everyone knowing about it.

Myths of the American West also supports this theory, stating that "fewer than ten bank robberies " took place between 1859 and 1900 "in all of the frontier west." But Wisniewski, Nakamura and Myths of America appear to have drawn their information from a study conducted by the Foundation for Economic Education in 1991 and published online in 2001. That was long before certain states, as well as the Library of Congress, began publishing historic newspapers online. These original resources reveal that while they were indeed uncommon, there were more bank robberies than just those committed by such famous figures as Jesse James and Butch Cassidy. Read on to discover the real truth about bank robberies in the Wild West.

Robbing a bank required planning

Planning a good bank robbery has always been key. In far-off New York, according to The Daily Beast, it took George Leslie three years to plan the 1878 robbery of the Manhattan Savings Institution, netting an amazing $2,747,700 — or just over $74 million today. Robbers in the West appear to have had much less time to plan, although outlaw Jesse James studied up on his first robbery "for weeks," says Plaza College.

There is more, too. Professional bank robber Joe Loya told Slate's Charles Duhigg that two of his most important steps were to remember to walk away from the robbery calmly instead of running and making the authorities believe he lived further away from the scene of the crime than he actually did. US News cites robbers who team up for a larger take and bring a gun, although the latter move can result in hefty jail time or worse, death. Especially in the West, says Myths of the American West, most common folks "carried weapons" according to historians, an obvious deterrent to bandits. In his book, Gunfighters, Highwaymen, and Vigilantes: Violence on the Frontier, historian Roger McGrath noted that in Bodie and Aurora, Calif., "most of the bankers were armed, as were their employees," making banks look much less appetizing to the average thief.

Where was the first robbery in the West?

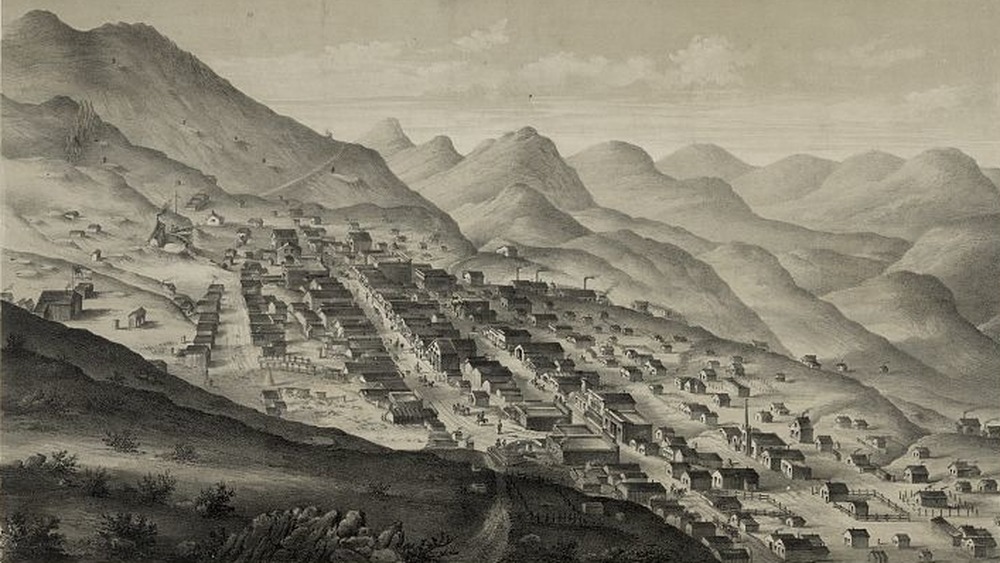

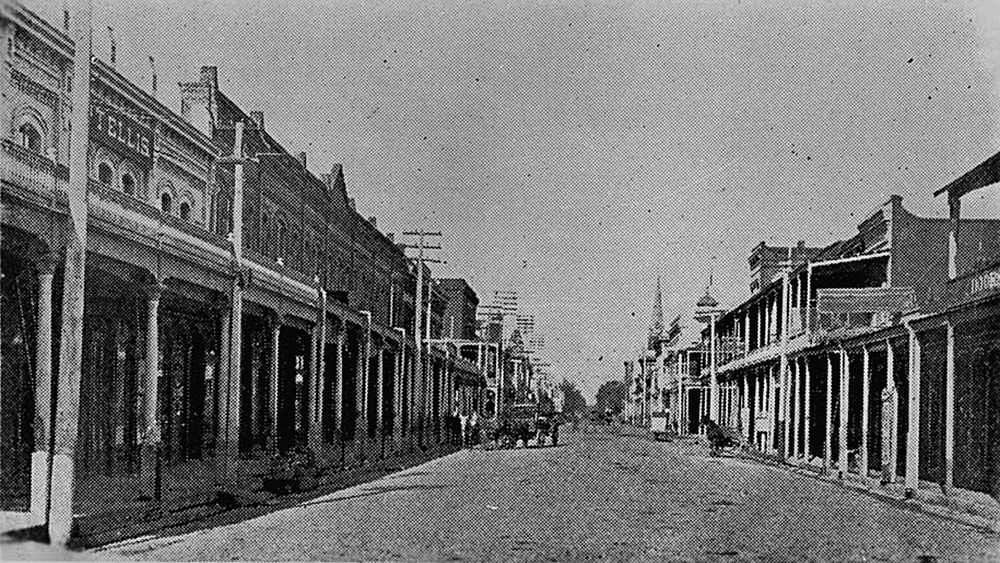

The first documented robbery in the West, according to a search of online newspapers, was in September 1860 at the mining community of Orleans Flat in California. In 1852, Orleans Flat was located on "a ridge located between the South and Middle Forks of the Yuba River," according to McGuires Place. By 1852 the town had a population of 500 and around 14 businesses and eventually became the "leading" mining camp in the area. News of the robbery appeared in the Daily National Democrat in Marysville some 60 miles away.

Turned out that Richard Curtis, an employee of the bank of Marks & Co., had made off with roughly $3,000. Shockingly, Curtis had been a trusted employee of the bank for quite some time. A follow-up article in Nevada County's Hydraulic Press noted that the loot consisted entirely of coins. So even if Curtis carried off only $5 dollar coins at 8.36 grams apiece, he was still lugging around some 11 pounds of money. And today, that $3,000 would be valued at just a bit less than a million dollars. Curtis appears to have gotten away with it, too. He was believed to have been headed to Washoe, Nev. (pictured), but there was no follow-up on the story. Marks & Co. eventually folded, and "by 1880 Orleans Flat was nearly deserted."

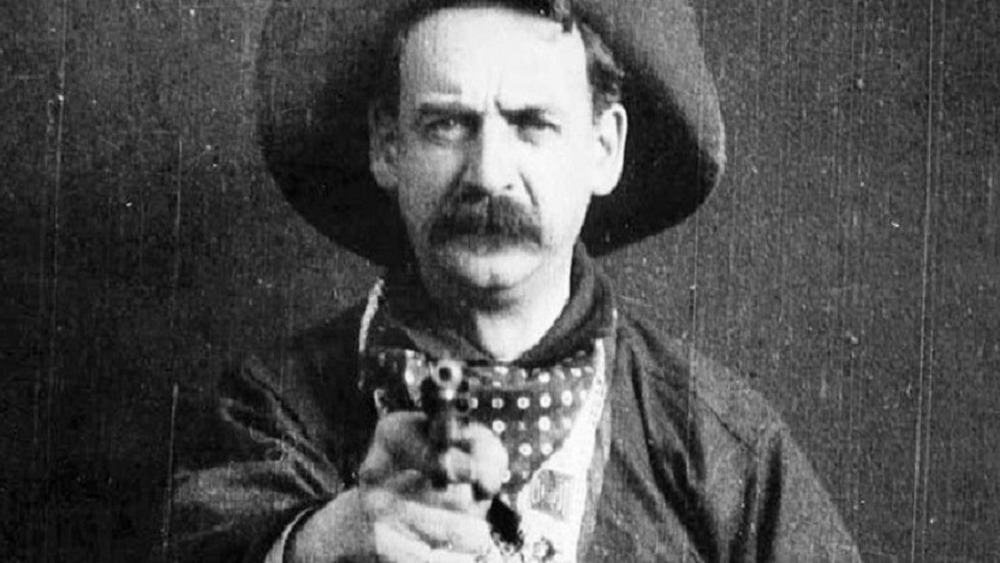

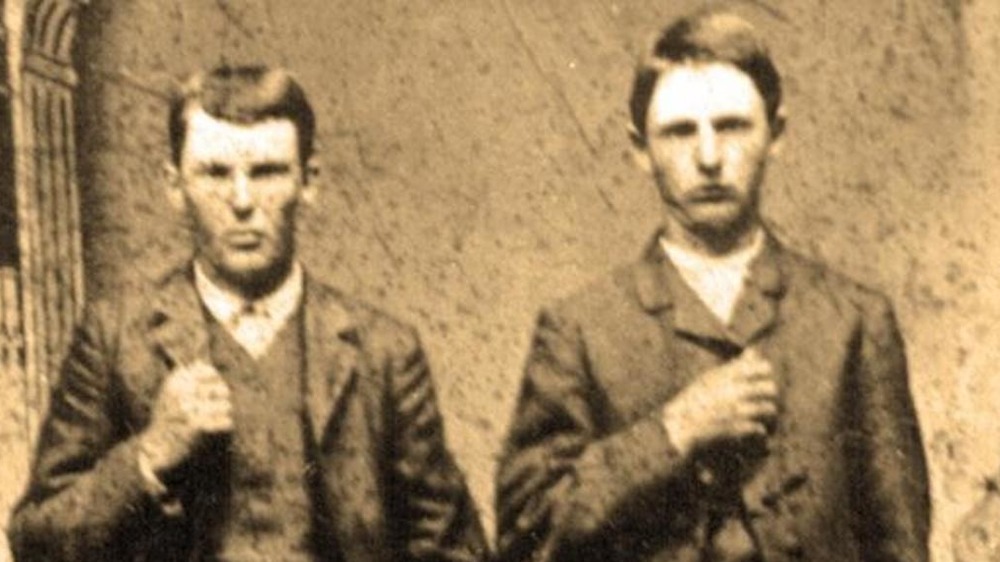

Jesse James committed the first armed robbery

The first armed robbery was committed by none other than Jesse James and members of his infamous gang. According to Legends of America, James and his brother Frank participated in William Quantrill's infamous raid at Lawrence, Kan., in 1863, wherein 180 people were killed, and two banks were robbed. Three years later, the brothers met up with fellow outlaw Cole Younger to plan another robbery in Liberty, Mo. On Feb. 13, 1866, says the Crime Museum, the men relieved the Clay County Savings Association of $60,000 and allegedly "wounded an innocent bystander" as they fled.

PBS however tells a different story. In this version, the gang "pistol-whipped a cashier" and killed "a passer-by." Plaza College says that although Jesse James helped plan the robbery, he wasn't present due to a chest wound. However it really happened, Jesse James and/or his gang were believed to have been responsible for at least 14 more robberies between 1866 and 1876, often killing or wounding bank employees and others. The biggest take was $14,000 at a Kentucky bank in 1868, followed by only $700 in Missouri the following year. Northfield History confirms the gang's last bank robbery in Minnesota was a complete failure as two of the eight robbers were killed, and two more were seriously wounded by angry citizens.

Chris Blair, the serial robber

For over a decade, Chris Blair and his partners committed robberies in California and Nevada. Blair's first known robbery, according to the Sacramento Daily Union, was in Virginia City, Nev. (pictured) in 1867. Two years later, writes the Sierra Sun, Blair and his buddies attempted to rob Fred Buckhalter's Bank in Truckee, Calif. As clerk William Lowden counted out "$4,000 in gold and silver coins," one of the men busted in and ordered him to fill a flour sack with the goods at gunpoint. In back, bank partner Henry Brown heroically scuffled with the others. The robbers left with nothing, and one of them accidentally shot himself in the foot.

Blair and friends were caught, according to the Sacramento Daily Union, but Blair was discharged for "lack of evidence." Next he robbed a jewelry store, was sentenced to prison, escaped, was caught, and finally served his time. More brushes with the law would come, namely a saloon burglary in January 1870. The last anyone heard of Blair was in 1879, when Nevada's Gold Hill Daily News reported that after getting out of jail he married a laundress in Bodie, Calif., and "made himself quite useful by keeping account of her customers' linen." Although it also was noted that he had "no superior in the burglary business," Blair apparently finally gave up his life of crime.

The failed robbery of Whipple, Winkley, and Toney

In 1873, California's Weekly Trinity Journal reported "one of the boldest attempts to rob a bank on record" in nearby Marysville (pictured). Robber Frank Whipple boldly strode into Decker & Jewett's Bank, approached owner John Jewett, put a gun to his head, and seethed, "Don't you move!" Jewett fell to his hands and knees, making his way over to clerk A.C. Bingham and calling out, "The gun!" Jewett was no fool. There were "four double-barreled shotguns" placed around the bank for just such an occasion. As the banker grabbed one and wrestled with Whipple, Bingham fired a pistol at the thief.

Bingham's shot, according to the Pioche Daily Record, hit Whipple in the neck. Outside, according to the Weekly Shasta Courier, Whipple's accomplices fled. Whipple also tried to flee, but Jewett and Bingham fired their shotguns, hitting him as he fell out of the front door. "Don't shoot," the wounded man cried out, "I've got enough; give me some water." Whipple, whose real name was James Collins, would die later that night as authorities looked for his partners. One of them was none other than former city marshal and fire chief P. W. Winkley, who planned the whole thing. The other was John Toney, who was later captured in Yuba City after a wild chase. Both men were sentenced to the penitentiary.

The robbery at Medicine Lodge, Kansas

True West's Mark Boardman puts it succinctly — when Lincoln County War veteran Henry Brown found himself in "financial trouble," he decided to rob a bank to catch up. There is, of course, more to the story. Heritage Auctions explains that Brown (formerly a friend of Billy the Kid) and three others walked into the Medicine Valley Bank in Medicine Lodge, Kan., in 1884 and tried to rob it. Before it was over, bank president Wylie Payne and chief cashier George Geppert were dead. Before he died however, Geppert somehow "managed to seal the vault." Brown and his accomplices fled, with nothing for their efforts.

As a posse formed, the Kansas Historical Society relates that Medicine Lodge citizens learned that two of the culprits were none other than Brown, who happened to be town marshal, as well as assistant marshal Ben Wheeler. They, along with robbers John Wesley and Billy Smith, according to Kansas Memory, were soon cornered in a box canyon, apprehended, and taken to jail. By then Medicine Lodge citizens were in an uproar, to the point that a lynch mob formed. When they opened the doors to the jail, the prisoners tried to escape. Brown was shot dead, and Wheeler was injured. He was taken, along with Smith and Wesley, and hanged from an elm tree outside of town.

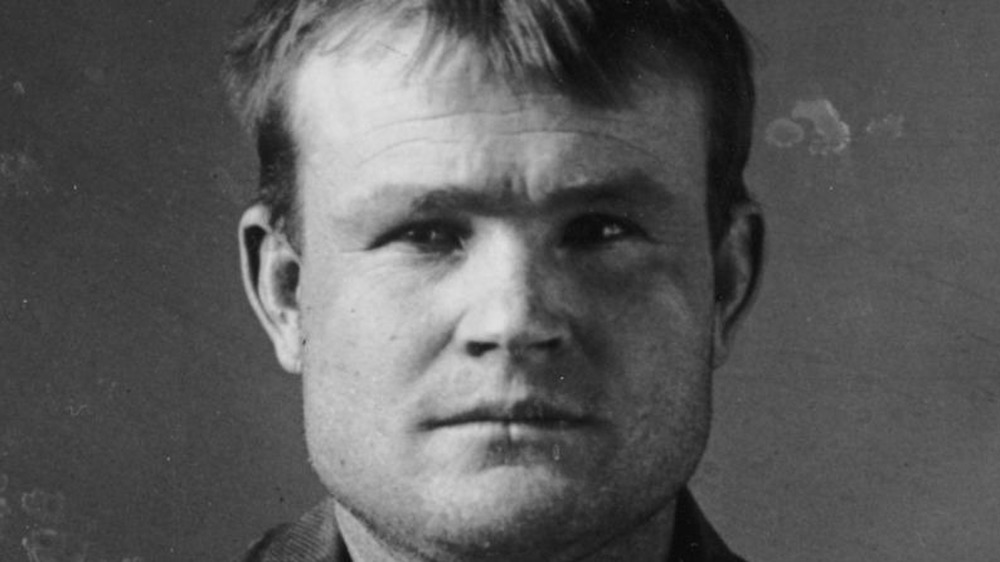

The robberies of Butch Cassidy

Butch Cassidy's first bank robbery in 1889 happened in Telluride, Colo. On June 24, writes True West historian Marshall Trimble, Cassidy and fellow outlaws Matt Warner and Tom McCarty simply walked into the San Miguel Bank, approached the only teller in sight, and "demanded cash" in the amount of $20,000 — roughly half a million dollars today. Cassidy already had relay horses lined up along the escape route. Utah says the men headed to Robber's Roost, their infamous hideout in Utah.

Only one other bank holdup is attributed to Cassidy. In August 1896, according to Yellow Pine Times, the outlaw, accompanied by Bob Meeks and Elza Lay, tied their horses in front of the Bank of Montpelier in Idaho and "urgently but politely invited" the cashier inside the bank. Employees were ordered to stand against the wall as the one of the men stepped behind the counter and took around $7,000 before the men rode off. Months later, the Montpelier Examiner printed a Salt Lake City Tribune article about former deputy sheriff John Gitting, who said he was camping on the Green River when Cassidy rode up "loaded to the muzzle" and dared to camp with him. Cassidy chatted amicably about the robbery and said he had "a bigger haul" awaiting him in Colorado. But as far as anyone knows, the Montpelier heist was his last bank robbery.

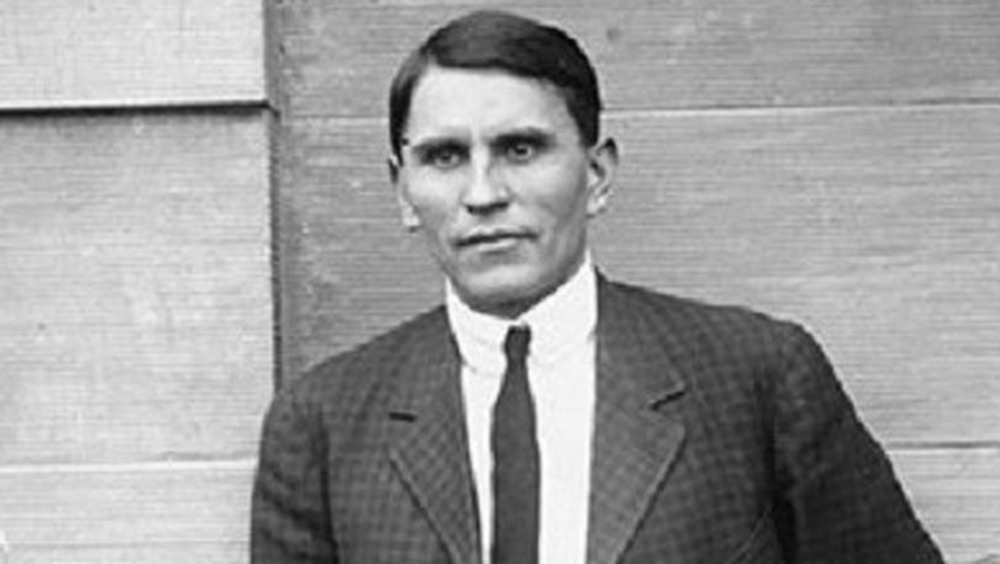

Henry Starr's 21 bank robberies

The New York Daily News says Henry Starr's outlaw relatives included Belle and Sam Starr, and his grandfather was the murderous robber Tom Starr. Notably, Henry Starr's first bank robbery attempts in 1892 failed miserably when U.S. Marshal Floyd Wilson tried to nab he and two accomplices, according to Legends of America. Wilson was killed, and Henry robbed two more banks in 1893 before he was caught. Of the latter robbery, in Benton, Ark., Henry revealed that he planned it for a week, studying the bank but also memorizing the getaway trail.

Luck was with Henry after he was finally nabbed in Colorado Springs, Colo., and sentenced to hang at Fort Smith, Ark. When fellow prisoner Cherokee Bill got hold of a pistol and holed up in a cell, Henry talked him into surrendering, commuting his sentence to 15 years. President Theodore Roosevelt pardoned him in 1903, but in 1908 he robbed a bank in Kansas, netting him more jail time until 1913, writes Marshall Trimble. Between 1914 and 1915, Henry robbed 14 more banks before being wounded during a holdup in Oklahoma. Paroled in 1919, he tried one more heist in 1921 but was shot in the back and died on February 22. "I always thought I'd die with my boots on," he said to his doctor, and proudly claimed, "I've robbed more banks than any other man in America."

The Dalton Gang's end in Kansas

Grat, Bill, Bob and Emmett Dalton were just cowboys when they decided to become lawmen after their brother Frank, a federal deputy marshal, was murdered in 1887, says Britannica. But their careers went out the window when in 1889 they turned to stealing. That ended, however, with their last bloody bank robbery in Coffeyville, Kan., in 1892. Bob, Emmett and Grat, along with Dick Broadwell and Bill Powers, decided to try robbing two banks at once. The men tied up their horses and divided up to rob both the Condon Bank and the First National Bank — but a passerby happened to recognize them.

History recounts that word quietly spread through town about what was happening. Armed citizens were quick to surround both banks as the thieves came outside to a hail of gunfire. When the smoke cleared, according to Legends of America, Bob, Grat and Powers were dead, as well as good guys Lucius Baldwin, Charles Brown, George Cubin, and Marshal Charles Connelly. An injured Broadwell escaped but died just outside of town. Emmett was also wounded and apprehended, later spending 14 years in Kansas State Penitentiary. Souvenir hunters stole pieces of clothing from the dead and other items, and both banks got nearly all of their money back. Today, artifacts and information from the robbery are entombed at the Dalton Defenders Museum, which Roadside America calls "an oddly-named nod to the martyred heroes of the day."

How Tom McCarty's 1893 robbery went bad

Butch Cassidy's bank-robbing buddy, Tom McCarty, thought he had it in the bag when he tried to rob the Farmer's and Merchant's Bank in Delta, Colo. in 1893. This was a family affair, according to the Fence Post. Accompanying McCarty was his brother Bill and his nephew, Fred, who was just a teen. Tom kept a lookout while Bill and Fred went inside the bank, but when cashier Andrew Blachly tried to warn others, young "trigger-happy" Fred shot him twice, killing him, says High Country Shopper. Things only got worse when Bill and Fred scooped up the loot and fled, leaving a trail of cash and coins as they went.

True West's own Bob Boze Bell writes that hardware merchant Ray Simpson heard the fuss. What the robbers didn't know was that Simpson was a dead shot and happened to be polishing his rifle on the store's steps as the McCartys made their escape. Running after them, Simpson shot the top of Bill's head clean off. Fred fired at Simpson three times before he himself was felled by Simpson from more than 100 yards away. Only Tom escaped, despite his horse suffering a bullet wound to the foot. He eventually ended up in Bitterroot County, Mont., where Legends of America says he was killed in a gunfight sometime around 1900.

The deadly bank robbery of 1896

On a quiet afternoon in October 1896, says History Net, outlaws Jim Shirley, George Law, and a third man known as "The Kid" Pierce (or "The Kid" Smith, according to The Fence Post) rode into Meeker, Colo. Their intended victim was a bank inside of the J.W. Hugus general store. Six men, including manager A.C. Moulton, were held hostage as bank cashier David Smith was ordered to hand over the money. All seemed good until a drunken "Uncle Phil" Barnhart sounded the alarm. Citizen Charlie Duffy immediately ran to the store where one of the robbers yelled "Hands up!" A quick Duffy said, "I don't have time," and skedaddled.

Some say the town was alerted when Law fired two shots during the heist. Either way, the bandits and their hostages exited to the street to find a "mob awaiting them." One hostage ran, then the others as gunfire broke out. Shirley and The Kid were killed as a wounded Law, according to The Craig Daily Press, "limped down a side street" before collapsing and dying later. Controversy remains over whether the bandits had the loot with them when they exited the store or left it in the bank. Surprisingly, Law, Shirley and The Kid are buried in marked graves at Meeker's Highland Cemetery. Today, visitors to the White River Museum can read about the incident, and the museum was putting together a historic display as of 2019.

The Cody, Wyoming heist of 1904

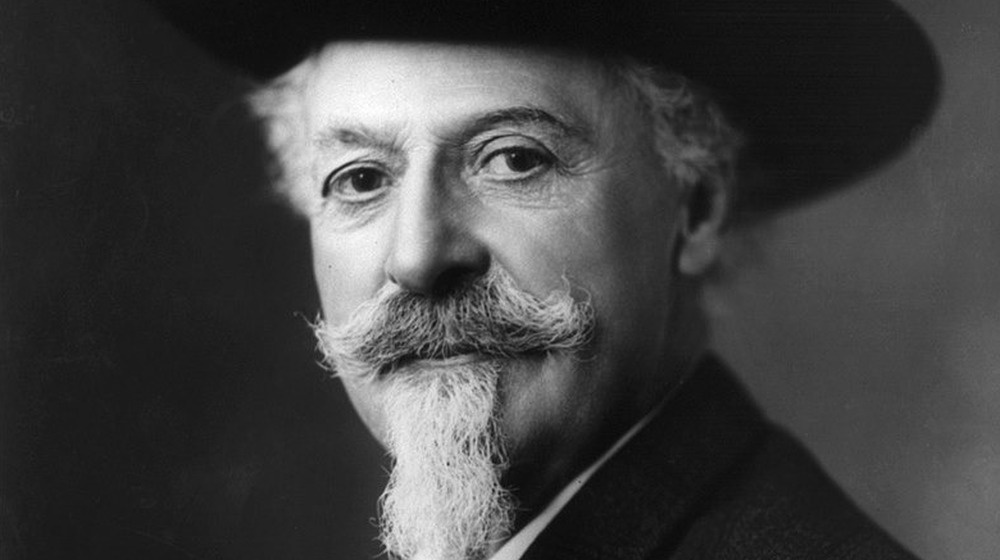

One of the last bank robberies in the Old West occurred in 1904 at Cody, Wyo. According to Wyoming Tales and Trails, two men, without masks, approached cashier Ira Middaugh at the First National Bank of Cody and tried to hold him up. Middaugh brandished a loaded gun instead and fired at the robbers but was shot dead as he tried to go for help. A party of hunters heard the gunfire and shot at the men, who managed to escape but without the money. The William F. Cody Archives, which gives a detailed account of the incident, says some citizens fired at the robbers as they fled. A posse of 100 men went in pursuit of the bandits, who were thought to be heading towards Hole-in-the-Wall, a popular hideout.

Newspapers who knew that Cody was named for famed showman Buffalo Bill Cody (pictured) assumed he was in on the chase, resulting in an amazing amount of mistruths and myths about the robbery, including that the noted outlaw "Kid" Curry was one of the bandits. Cody did express interest in the capture of the robbers but did not participate in the hunt for them. For months, newspapers reported the "capture" of various suspects, but they were never caught. Today, Waymarking says the original bank no longer stands. Only Ira Middaugh's grave remains as a testament to the hero who saved Cody's First National Bank.