The True Stories Behind These Strange And Mysterious Artifacts

From the Sword in the Stone to ancient Egyptian airplanes, strange and mysterious artifacts summon people to put away their iPhones, don a fedora, snap a bullwhip, and get their faces melted. Some artifacts are intoxicating through their storytelling or by the puzzles they present. Basic questions such as who made an item, why they made it, and what it does fascinate all armchair archaeologists. While answers to these questions that involve the lost city of Atlantis or alien technology have less than zero credibility, just the fact that these outré explanations exist demonstrates how everybody wants to be Indiana Jones.

Yet all artifacts, even the most mysterious ones, are grounded in history and science. This article will take a look at the true stories behind some of the world's strangest and most mysterious artifacts. We can assure you that none of these artifacts' histories involve UFOs or sunken continents.

Did the Ark of the Covenant actually exist?

The most venerable of artifacts is the Ark of the Covenant. According to National Geographic, the Ark isn't the true artifact. Instead, the Ark was the golden container that the Hebrews crafted to house the stone tablets containing the Ten Commandments. The Ark was credited to several Old Testament miracles, including halting the course of the Jordan River and helping the Israelites take down the walls of the city of Jericho. After the Kingdom of Israel was established, it was kept at the First Temple in Jerusalem until the Babylonian Empire conquered Israel in the sixth century BCE. After that, the Ark vanished.

There are a variety of theories as to what happened to the Ark. Some say that it might be buried below the old Temple, but since the space is now occupied by the Islamic holy site of the Dome of the Rock, excavation is out of the question. Another theory states that the Ark made its way to Ethiopia, where it is kept at the St. Mary of Zion cathedral in Aksum. Smithsonian Magazine reports that it is guarded by a virgin monk who cannot leave the grounds until death. The monks are also the only ones who can view the thing, which prevents any verification. Still, even if scholars could see it, they would have trouble concluding that the artifact in Ethiopia was the Ark. The mystery of the Ark is likely never to be solved.

Nobody ever sees these Japanese treasures

According to National Geographic, the emperors of Japan represent the world's "oldest continuous hereditary dynasty." Jimmu, according to a myth related by Reuters, became the first emperor in the seventh century BCE. He was a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami, who bequeathed to Jimmu's line three sacred treasures: the mirror, the sword, and the jewel.

These relics were passed down through the centuries. The mirror, Yata-no-Kagami, resides at the Ise Grand Shrine. The sword, called Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, is at the Atsuta Shrine. The jewel, known as Yasakani-no-Magatama, is kept in Japan's Imperial Palace.

Although their history is known, nobody save the Emperor and a few high Shinto priests know what the three sacred treasures look like. They are stored in boxes and kept out of view. Still, scholars have made educated guesses based on other artifacts from the period. The mirror is probably of well-designed bronze, the sword is probably a practical piece of iron weaponry, and the jewel is likely filled with comma-fashioned beads.

Will these boxes ever be opened to the public? Probably not. In correspondence with CNN, Mickey Adolphson, a University of Cambridge professor of Japanese studies, wrote, "The not showing of such treasures is of course an important part of the strategy that adds mystique, and thus, authority, to the objects. Were they for everyone to see, they would not have the same staying power."

An ancient Greek Rube Goldberg device

In the first years of the 20th century, divers hauled out from the Aegean Sea one of the most complex artifacts of antiquity. This item, known as the Antikythera Mechanism, was recovered as three flattened pieces of bronze filled with toothy gears and measured marks, as related by Smithsonian Magazine. It seemed to shout, "I am a scientific instrument!" But initially, no scholar could figure out what it did. Some claimed it must have come from aliens. It was only after the pieces were studied via X-ray in the 1970s and 1990s that it was concluded that the device was used in astronomy.

The real breakthrough came in 2006, when CT scans of the mechanism showed it full of dials, discs, and inscriptions giving instructions on its use. It became clear that the artifact was used to chart the course of the heavens. When properly used, the Antikythera Mechanism could tell when particular stars were rising or falling. It could also predict solar and lunar eclipses. It was so complex, with orbs representing planets on its face, that Rube Goldberg would have found it inspiring.

The Antikythera Mechanism was essentially an ancient computer sans electricity. Careful study shows that it probably came from the Island of Rhodes circa the first century BCE. Yet, as Smithsonian details, it may have had far earlier predecessors going back to the ancient Babylonians. It is still being studied today at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

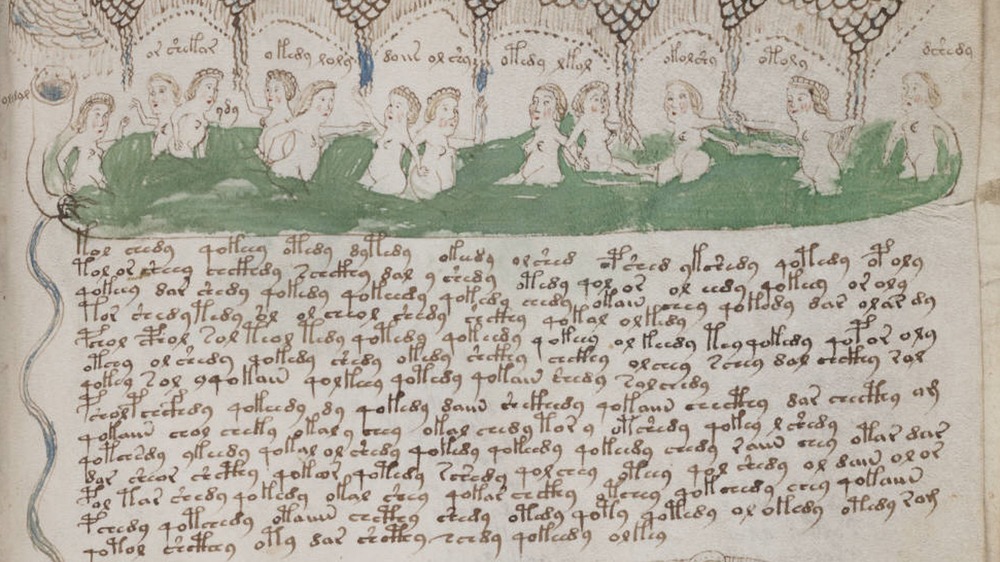

The weirdest manuscript in the world is kept at Yale

In the Beinecke Library at Yale University is the trippiest book in human history. As told by the Beinecke Library, in 1912, a rare book dealer named Wilfrid Voynich came across a 15th-century codex that has defied all decipherment and explanation. This book is known as the Voynich Manuscript.

The codex is divided into six sections. One contains illustrations of unknown species of plants. The second has zodialogical imagery that seems to be astronomical in nature, but it doesn't make sense. There are unknown constellations on display, for example. Another section has female nudes swimming. One other section seems to have pharmaceutical drawings. And there's tons of writing, all in an undeciphered script.

According to The Art Newspaper, attempts to decipher the manuscript have been ongoing. The latest claim of a breakthrough came in 2020, when a German Egyptologist posited that the mysterious script is based off of Hebrew. On the other hand, according to New Scientist, linguists have studied the Voynich Manuscript using a statistical analysis of the appearance of characters and have concluded it is just an elaborate hoax. Other linguists disagree. Hoax or not, the Voynich Manuscript is a worthy artifact based on the intensive debate and study it has created – as well as launching alien visitation conspiracy theories.

Costa Rica's Big Balls

In 2014, UNESCO designated a number of curious artifacts in Costa Rica in the Diquís Delta as part of a World Heritage site. These are Las Bolas Grande, or the "Giant Balls" which are one of the most puzzling artifacts of pre-Columbian civilization. These nearly perfect man-made spheres have diameters of up to 2.57 meters (8.4 feet). It is believed that Las Bolas, more properly called petrospheres, were crafted as far back as 300 BCE, according to The Costa Rica Star, and as recent as 1500 CE, according to The Costa Rica News. Quite a big range, indeed.

The artifacts were first found in the 1930s by employees of the United Fruit Company, who were clearing rainforest for development. Some balls were destroyed in the mistaken belief that there was treasure inside.

Curiously, Las Bolas were made without metal tools, and they seem to have no clear purpose. Some have posited that the balls were used as astronomical symbols. This is impossible to prove, since most of the balls have been moved away from their original positions. They may have also been used as part of some sort of religious observation. Yet all this is speculative. Without further evidence, Las Bolas will remain a mystery.

Why the French Foreign Legion venerates a prosthetic hand

Strange as it may sound, the French Foreign Legion venerates a prosthetic hand.

The story, as told by the French Foreign Legion, goes back to 1863, when France sent an intervention force into Mexico. That April, a detachment of 65 legionnaires and officers on reconnaissance arrived at the abandoned village of Cameron (Camerone in French). On April 30, they encountered a large Mexican force of 2,000 infantry and cavalry.

The Legion's commander, Captain Jean Danjou, who had lost his left hand in an action in Algeria a decade prior, would not surrender. Instead, the legionnaires holed up inside a hacienda, shared a bottle of wine, and got down to a fierce day of hopeless fighting. Danjou was killed, as were most of his men. When the last three legionnaires were captured, the Mexican commander, Francisco de Paula Milan, exclaimed, "That's all what is left?? These aren't men, they are devils!" A total of 12 legionnaires survived wounds and imprisonment. About 300 Mexican soldiers were killed or wounded.

The Battle of Camerone was an inspiration to the French Foreign Legion and established its reputation. It also was the origin of a tradition. According to the French Foreign Legion, every April 30 is celebrated as Camerone Day. As part of the ceremonies, the prosthetic hand of Captain Danjou is presented to the public, making it one of the most interesting artifacts in history.

Is the Hope Diamond really cursed?

The Hope Diamond is one of the most famous jewels in history, but is it cursed? Its story, as told by the Smithsonian, begins in the 17th century, when King Louis XIV of France purchased a 112-karat blue diamond which originated from the Kollur mine in India. The king recut it into a 67-karat stone called the "French Blue." This stone was lost after it was seized from King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution. The pair are among the first to have supposedly fallen victim to the curse since they were guillotined. As for the jewel, it turned up in the possession of Henry Philip Hope in 1839, recut into a 45-karat stone. The Hope Diamond's curse then really kicked in.

In tracking the gem's history, PBS lists 29 individuals who suffered misfortune ascribed to the diamond. This includes individuals who died by suicide and murder, as well as Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who lost the Ottoman Empire. Many cases are unsubstantiated, but the allegations of a curse have driven this object's allure. The last person supposedly stricken by the Hope Diamond's curse was James Todd, a mailman who delivered the diamond to the Smithsonian Institution. His leg was crushed in a truck accident, he then suffered a head injury in another automobile accident, and finally, his house burned down.

According to Forbes, the diamond attracts about seven million visitors yearly to the Smithsonian and is worth about $350 million.

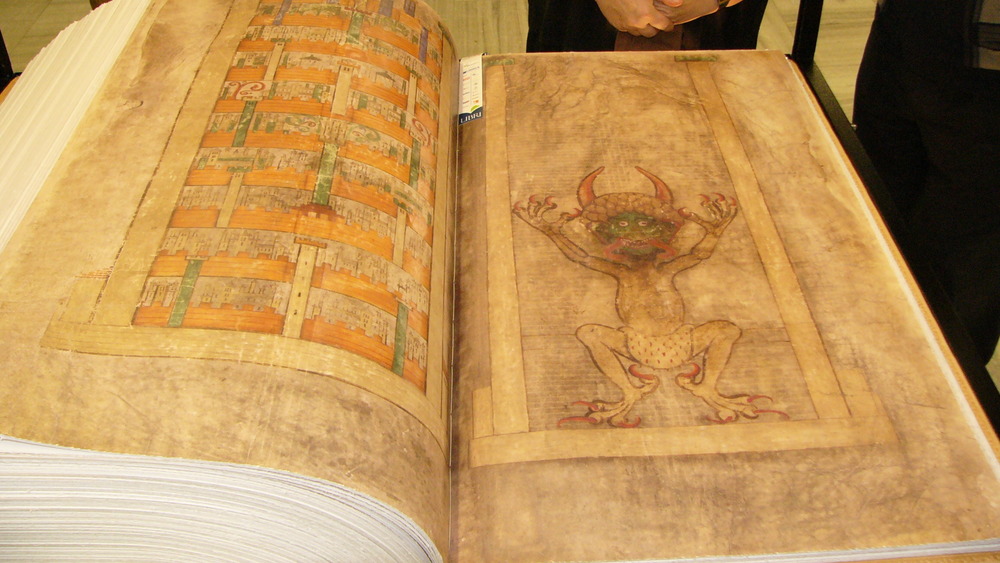

Behold the Devil's Bible!

Sometime in the 13th century, a monk created a book for the ages – but apparently only with infernal aid. The legend, as related by National Geographic, is that the Devil made a pact with the monk, and in a single night, he created one of the most monumental artifacts of the Medieval period, the Devil's Bible.

At 165 pounds and 620 vellum pages, this massive book is more formally called the Codex Gigas, meaning "Giant Book." However, for those of you wishing to summon Old Scratch yourself, you may be disappointed. The Devil's Bible contains hardly anything satanic. It sports the Old and New Testaments as well as other writings, which, according to the University of California at Santa Barbara, include The Antiquities and The Jewish War by Josephus, the Encyclopaedia by the scholar Isidore, medical texts, and histories. The only appearance of Satan is on page 290. Interestingly, this is the only illustration of the Devil in a bible from that period.

In reality, the Devil's Bible probably took many years to create, perhaps even as a form of penance stretching over two decades. A fully digitized version of the Codex Gigas is available through the National Library of Sweden, where it currently resides.

Roman dodecahedrons: Nobody knows what these things were for

Some artifacts, no matter how simple they appear, defy explanation. Such is the case of Roman dodecahedrons dating to the second and third century CE. According to Mental Floss, each object is like a 12-sided die with points coming out and each side having a hole of a different diameter. Since people started finding these artifacts across Europe in the early 18th century, they've tired to figure out their purpose. However, these objects have no documented mention in the historic record. Still, they have been found among troves of valuable objects, leading many to conclude there was value to them. This has led scholars to posit many possible theories.

Researcher Amelia Carolina Sparavigna has suggested the dodecahedrons were used as range finders by peering through their various holes. Others have held that they may have just been children's toys. Still others have suggested candleholders. The Hunt Museum, where one of these artifacts is on display, speculates that it may have been used as the head of a mace. The mystery continues, but it does lead to some creative solutions among dodecahedron-obsessed amateurs. One of the more creative theories was that it was used as a knitting tool. While any of these may be true, ancient primary evidence will ultimately need to be uncovered to verify what the heck these things did.

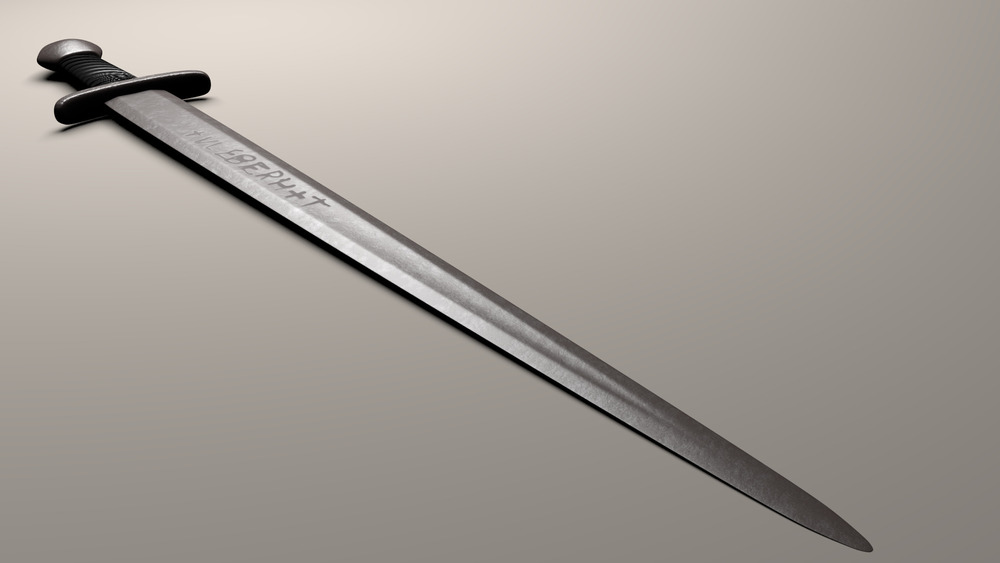

Ulfberht's Mighty Swords

Ancient swords are the stuff of fantasy tropes, such as King Arthur's Excalibur. But there is one cache of about 100 medieval swords that were so far ahead of their time that one may think they were conjured by the Lady of the Lake. In fact, these weapons were created by Ulfberht (usually etched into the blade as "ULFBERH+T"). Anders Winroth tells a little bit more about these swords in his book, The Age of the Vikings.

The Ulfberht swords, unlike other contemporary Viking swords, were forged of a steel with an unusually high degree of carbon content for that time. This produced harder and tougher weapons that could shatter the swords of the people whom the Vikings raided. These weapons have been found all throughout Europe during the Viking Age, which stretches across three centuries from 790 to 1100 CE, according to National Geographic. The problem was that swords of this type were not forged in Europe, since the technology was not advanced enough.

Winroth speculates that the swords must have been imported from Persia, India, or Central Asia, where such forging techniques were in practice. Another issue is Ulfberht, since the swords are dated over the course of three centuries. Ulfberht was less likely to be a person and more of a brand, be it a family or workshop that produced some of the finest weapons of medieval Europe. PBS even produced a documentary on Ulfberht's mighty swords.

Does the Copper Scroll of Qumran lead to treasure?

The Dead Sea Scrolls are one of the most famous archaeological finds in history. Reuters tells us this trove of ancient Jewish material dating from about 2,000 years ago provides insight into the culture and beliefs of that people. One of these scrolls, however, may lead to riches. In 1952, in Qumran, archaeologists found a scroll made of copper. The copper was so brittle that the scroll could not be unraveled until finally, according to the University of Southern California, they cut it into segments. The copper scroll was baffling, since it gave instructions on where to find treasure which researchers believe was once held at the Temple in Jerusalem. A translation of the opening text reads: "In the fortress which is in the Vale of Achor, forty cubits under the steps entering to the east: a money chest and it [sic] contents, of a weight of seventeen talents."

It was estimated in 1960 that the value of the treasure as described on the Copper Scroll was worth over $1 million. However, that would be based on the value of the gold and silver. As artifacts, the treasure would be worth far more, with estimates on the internet ranging into the billions. Has anybody found the treasure? No. But that doesn't stop people from looking for it. It may be that the treasure never existed, or it was found long ago. Today, the Copper Scroll resides at the Jordan Museum.

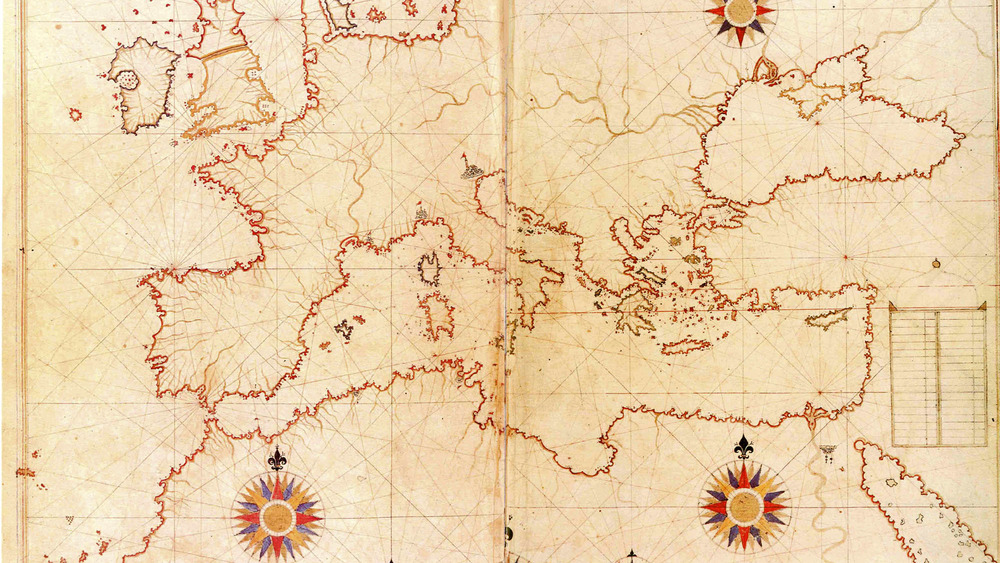

Does a 16th-century map show Antarctica three centuries before it was discovered?

Antique maps are fascinating as an artifact of history and art – who doesn't like seeing various krakens all over the globe? One curious map, according to Atlas Obscura, was created by the Ottoman admiral Piri Reis in 1513.

According to the Sixteenth Century Journal in a review of a book about the map by Gregory C. McIntosh, Piri Reis crafted on gazelle skin highly accurate maps for the time period, especially in the case of South America and the as-yet unknown Antarctica (shown without ice). There has been wild speculation on how such a map could have been created. Perhaps Antarctica was Atlantis – just do a search for "Piri Reis Atlantis," and you'll see how popular this theory is. Wilson explains that much of this speculation is because there isn't a full understanding of the map or the time period it came from. Piri Reis used maps from the Portuguese, who visited South America. As for Antarctica, this can be explained by the general theory of Terra Incognita Australis, wherein geographers had speculated that there had to be a massive southern landmass to counterbalance the northern ones.

Atlas Obscura reports that Piri Reis filled the map with sharp comments such as, "This country is a waste. Everything is in ruin and it is said that large snakes are found here. For this reason the Portuguese infidels did not land on these shores and these are also said to be very hot."