What It Was Really Like To Be A Cold War Spy

Saying that the Cold War was a tense period of time is surely understating the matter. From the end of World War II, the allies of the United States and the Soviet Union quickly turned against one another in a battle for worldwide domination. The simmering conflict lasted until 1991, History reports, though the collapse had been preceded by years of de-escalating tensions between the two superpowers.

Stakes were high during the height of the Cold War, however. For many, the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, where it appeared most likely that the Cold War was going to turn dangerously hot, was a clear example of the danger posed by the opposite side. All of this tension meant, at least to officials, that every single advantage, no matter how small or how long it took to gain it, could mean the difference between maintaining the peace and dealing with World War III. This, then, is where the spies came in.

Throughout the course of the Cold War, spies played a vital part in establishing that edge. Yet, few of them were glamorous James Bond types. The true reality of spycraft during this era could be at turns dirty, dangerous, and even utterly boring. Yet, some clichés are surprisingly close to the truth. Ultimately, this was work that many considered important but came with surprising results. Here's what it was really like to be a Cold War spy.

American Cold War spies loved technology, while Soviets kept it old school

Though the common conception of Cold War spycraft seems to center on a wide array of tech, the truth of who embraced gadgetry and how is a bit more complicated.

According to The History of Science Society, spy agencies within the U.S. generally embraced technology when it came time to take a look at the Soviets and their activities. This led to the development of major technological advances, like nuclear submarines and spacecraft, and satellites that could listen in on the activities of the enemy. The Soviet Union, meanwhile, tended to focus on human-based intelligence, relying on agents to gather information in a more old-school style.

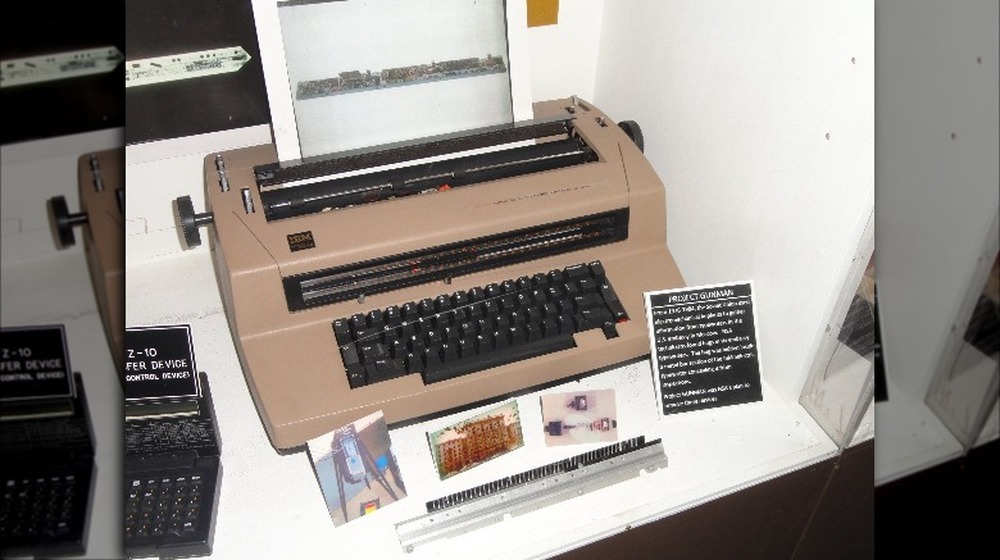

Yet, as much as the Soviets leaned on classic tactics, they weren't above employing technology here and there. According to Popular Mechanics, the KGB planted a bugged typewriter in the U.S. embassy in Moscow some time in the 1970s. The National Security Agency eventually discovered that information was being transmitted, but it took an exhaustive search of all the embassy's electronics to discover the altered typewriter and its transmitter.

Some Cold War spies went undercover for an incredibly long time

Though some spies could expect to receive relatively short-term assignments, others were saddled with espionage terms that could last for months and even years. That's more or less the plot of The Americans, a modern TV series focusing on Soviet sleeper agents. According to Quartz, The Americans is based in part on real stories of undercover Russian spies, some of whom have been uncovered in the U.S. well into the present day.

One of the most notorious long-term agents may well be a man named Jack Barsky. As the BBC reports, Barsky actually began life as an East German named Albert Dittrich, who was recruited by the KGB in the 1970s. They secured the identity of a young boy who had died in 1955 and used it as the basis for Dittrich's cover story. Barsky later admitted that legal red tape — like difficulties getting a passport — kept him from accessing any serious state secrets. He also reports that his superiors in Moscow had a pretty poor understanding of American culture.

When the FBI finally apprehended him in the 1990s, it was because Barsky had admitted he was a KGB agent in an argument with his wife. Their house was, unsurprisingly, bugged. But, the FBI eventually determined that Barsky was no longer a threat, and they, in fact, helped him become an American citizen. "I am not German anymore," Barsky now says. "The metamorphosis is complete."

Double agents were everywhere in the Cold War

Double agents, who pretended to work for one side while actually supporting another, were a regular feature of Cold War spycraft. And it seemed like they were everywhere in the world of espionage. For those on the anti-Soviet side of things, there was the worrisome tale of George Blake. As the BBC reports, Blake was involved with the British intelligence service but was also a Soviet agent, leading to the uncovering of at least 40 MI6 agents and his own imprisonment in 1960. Six years later, he escaped jail and lived in Russia until his death in 2020. He never fully explained why he had betrayed one side for another.

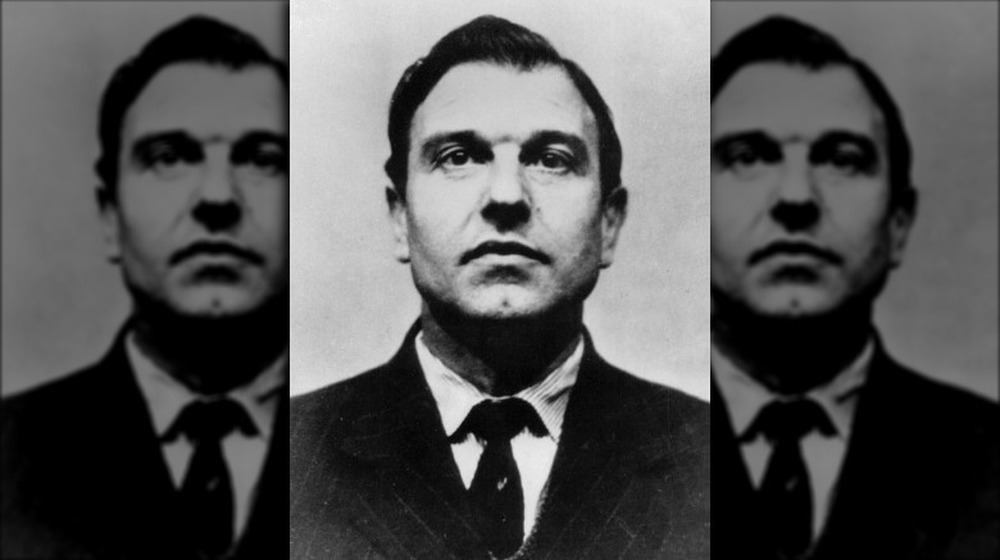

The Soviet Union also had to worry about double agents within their own network. History says that one of the longest-serving moles was a man named Dmitri Polyakov, who had been feeding information to the U.S. for over two decades. Polyakov seemingly disappeared after he sent out a distress signal in 1984 via a recipe published in a Russian magazine. Later, a 1990 article printed in Pravda, the newspaper of the Communist Party, claimed that he had been captured and killed.

Yet, some suspect that Polyakov may have in fact been a triple agent who held back on the most useful information. Still, they appear to be in the minority. Many intelligence experts today believe that Polyakov provided valuable information that kept the Cold War from becoming an outright conflict between nations.

Cold War spies were often women

Hopefully, it's not surprising to too many modern readers to learn that women were always valuable espionage agents, though plenty of people in the Cold War were routinely surprised to learn this very fact.

Female spies made their marks on both sides of the ongoing conflict. In Hungary, which remained nominally independent during the Cold War but was closely associated with the Soviet Union, women were employed in the nation's intelligence services. Yet, according to the Journal of Intelligence History, they were frequently forced to act out sexist attitudes prevalent at the time. Women were often relegated to mundane secretarial work, while those that went out in the field were pressured to use feminine wiles in "honey trap" schemes that required the seduction of men in exchange for information.

Though the U.S. and its allies weren't much better when it came to giving female agents a chance, a few women managed to make their mark. Take Martha Peterson, who was an agent working in 1970s Moscow. Drew Magazine reports that she was involved in clandestine information drops, eased by the Soviet assumption that women simply didn't work as U.S. secret agents. Yet, in 1977, she was briefly waylaid by KGB agents who attempted to take her surveillance equipment. They didn't secure it, but Peterson was kicked out of the country, and The Washington Post eventually blew her cover with a front page photo of the incident.

Being caught as a spy could lead to dire consequences

Though close calls in spy movies are thrilling, real life espionage agents didn't want to get anywhere close to being found out. The consequences of being caught could be utterly dire, ranging from gruesome torture to executions.

Even the most domestic of spies weren't immune from the severest punishments. According to History, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were put to death for their part in a postwar Soviet plot, even though they were parents to two young boys. They both died on June 19, 1953, because they took part in passing on information about the U.S. nuclear program to rival Soviet scientists. They were betrayed by David Greenglass, Ethel's brother, who had worked at the Los Alamos National Lab that had developed the American nuclear weapons program.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower later said that "by immeasurably increasing the chances of atomic war, the Rosenbergs may have condemned to death tens of millions of innocent people all over the world." Their short trial and executions remain controversial to this day.

Sometimes, spies who saw that they were about to be caught took dire consequences on themselves. According to a 1976 article from The New York Times, double agent Norman J. Rees warned a Dallas newspaper that, if they ran an article exposing him, he would kill himself. The newspaper claimed that the story "could not be suppressed" and went ahead, after which Rees made good on his promise.

Cold War spy gadgets were common and sometimes really weird

Though some spies and spy agencies preferred to focus on old school human-based techniques, it was nearly impossible for them to do their thing without at least some technological assistance. Some of this could be as mundane as cameras, while other variations on spy tech could get pretty weird.

Some of those gadgets, according to History, relied on animal assistance, such as a pigeon-mounted miniature camera. Other experimental devices included an "Insectothopter" camera made to look like a dragonfly, as well as a robotic catfish used to collect water samples near nuclear plants. And, yes, spies did occasionally wear cleverly hidden body cameras to snap photos while on assignment.

Funny as some of these may seem, technology could also be used for darker purposes, as when a seemingly innocuous umbrella was used to kill a man. As PBS reports, Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov at first appeared to have just bumped into a man on the streets of London. However, he died soon after in September 1978. Investigators eventually found that he had been injected with a poison-infused pellet via the strange man's umbrella tip, which had made contact with Markov's thigh. Though the assassin was never identified, it's all but certain that they were a Soviet spy also working as a deadly hitman.

Disguise tricks helped spies evade capture

Though it may seem like a concept ripped straight from the flashy, unreal world of cinema, spy disguises really were a thing during the Cold War. In fact, reports PBS, it was so important to spycraft then and even now that, as retired CIA officer and agency Chief of Disguise Jonna Mendez says, "With disguise, we just surpassed anyone's dreams. I mean, we had some amazing successes." She would know, having spent time with husband Tony Mendez, also part of the CIA's Office of Technical Service, in Moscow during the Cold War. The pair even helped to develop "Jack in the Box," an inflatable yet realistic dummy used to throw Russian pursuers off an agent's trail.

Wild as things like Jack in the Box may sound, however, Mendez maintains that the best disguises were ones that helped spies effectively disappear. As a disguise officer, CBS News says, she helped agents build up an entirely new look, including adjusting the smallest mannerisms and even seemingly big clues like an agent's gender. This was accomplished largely with careful training but also a good dose of classic moves like new hairstyling and a fresh pair of glasses. With the constant need to lose Soviet agents on their trail, something as simple as a modified walk and a new wig could be the difference between a successful mission and a disaster.

Some Cold War spy tricks were inspired by magicians

Much of spycraft is pretty mundane. A good Cold War spy seems to have been someone who was well-situated, perhaps with a strategically important job or a convenient relationship connection. The spy really just needed to be observant and cautious, perhaps with the help of a small, concealed camera and a drop site or two. Yet, it seems that there was always room for something a bit more fantastical than merely shaking a tiny film canister into some bushes.

That's because, as the wider public learned in 2009, the CIA wasn't above using a bit of magic. Specifically, as ABC News reports, at least one declassified manual reveals that stage magic was considered a part of the Cold War spy toolkit. Originally, many believed these rumors to be untrue, but it turns out that magician John Mulholland really did help out the spy agency in the 1950s.

Two of Mulholland's surviving manuals were combined by retired CIA agent Robert Wallace and historian H. Keith Melton into The Official C.I.A. Manual of Trickery and Deception. The documents taught agents how to use things like sleight of hand to grab documents. So, too, could a classic stage technique like misdirection be useful when a spy needed to slip something into an opponent's drink. Given the CIA's secrecy, it's hard to confirm that Mulholland's writings directly influenced fieldwork, but retired agents confirm that they used very similar techniques during espionage operations.

Spy rings were uncovered in shocking ways

Though many of us today may think of spies operating as roguish lone wolves, a la James Bond, the reality of Cold War espionage meant that agents often had to work together. Frequently, they formed spy rings to ease the passage of clandestine information. Yet, when these rings were uncovered, they released shockwaves that could not only take down a multitude of agents but shake a government to its very foundations.

Take the Soviet spy ring that caused a scandal in Canada. According to the CBC, it all started in September 1945, when Igor Gouzenko refused to go home. The Soviet cipher clerk had been ordered to leave his post at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, but the allure of Western life proved strong. Gouzenko snagged sensitive documents and, after a few weeks, walked into the office of the Ottawa Journal with a figurative bombshell. He told reporters there, "It's war. It's Russia," meaning that the Soviets had already commenced spying on their supposed allies. It shattered fragile alliances and touched off tense relations between Canada and the Soviet Union.

London was also the site of yet another dramatic spy ring revealed only 15 years after Gouzenko's exploits. Politico reports yet another Soviet-sponsored ring was uncovered in 1960 London involving a nearly impervious agent with no diplomatic ties. The Portland Spy Ring, as it came to be known, was uncovered after British MI5 agents doggedly followed suspicious members of the Underwater Detection Establishment.

A few Cold War spies committed espionage in the name of science

Assuredly, many people involved in espionage and counter-espionage throughout the Cold War wondered why, exactly, a spy would take on such dangerous and duplicitous work. Sometimes, it was for money. Sometimes, it was for the hope of a new life or for serving their home country. Sometimes, it was for science.

According to the Science History Institute, scientists of the Cold War era were uniquely situated to commit espionage. Often, they were investigated for extensive traveling and freely speaking with fellow scientists, regardless of whether or not they were on opposing sides of the conflict. The stakes, which involved technological advancements like high-altitude planes, spy satellites, and nuclear bombs, were high enough as to keep the CIA and other intelligence agencies on high alert.

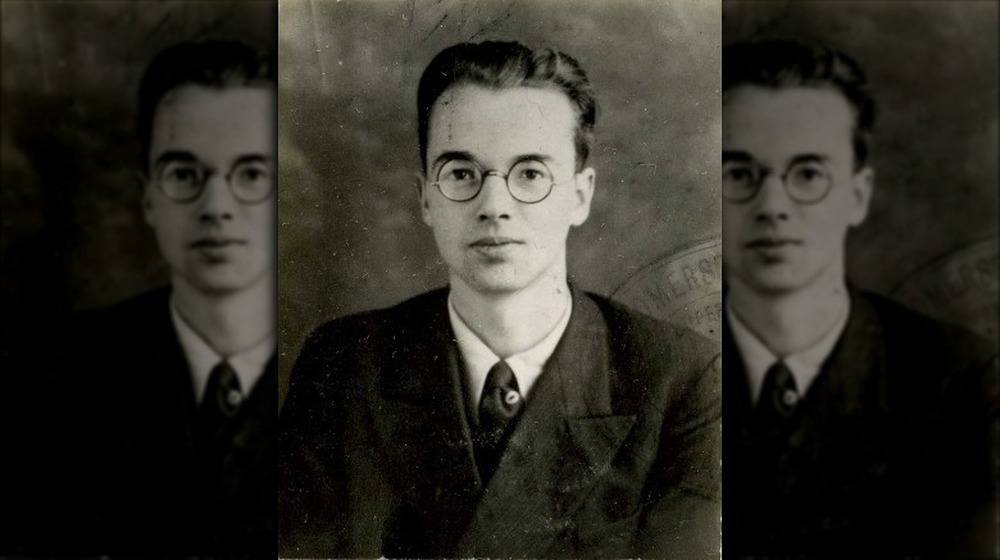

These concerns were far from theoretical, as real spies had breached top secret institutions early on. The Baltimore Sun reports that a still-unnamed American scientist code named "Perseus" may have leaked information from the Los Alamos Nuclear Lab to Soviet scientists. And Nature reports that Klaus Fuchs, a theoretical physicist from Germany, also helped the Soviet Union grow its weapons program by passing along scientific documents. Fuchs eventually confessed in 1950 and was hit with a 14-year prison sentence.

Some Cold War spy mysteries may never be solved

Moles were rampant in the Cold War espionage world, but one who may have been behind a disastrous year still hasn't been uncovered. Smithsonian Magazine reports that, in 1985, the KGB uncovered a large number of undercover agents, executing ten of them. This kicked off an extensive counter-espionage program undertaken by the CIA to ferret out the mole amongst them. Initially, authorities believed that they had found him in Aldrich Ames, an agent arrested in 1994.

Yet, it soon became clear that at least one other mole was involved. According to Ames' confession and the CIA timeline, there were three agents who had been uncovered before Ames began his double agent activities. Despite the agency's efforts, the purported mole has never been uncovered. That's still alarming for CIA officers, who had only uncovered three major moles, including Ames, in the history of the agency. The threat of a mysterious, perhaps still active double agent could potentially put all operations during the high stake Cold War at serious risk.

All the Cold War spying may not have been worth it

There's no doubt that many Cold War spies worked extraordinarily hard and often completed their missions under potentially deadly conditions. Yet, as historians and analysts look back on the history of Cold War espionage and spycraft in general, many wonder if it was all truly worth the effort. Consider the harsh fact that intelligence can be easily misinterpreted or ignored by one's superiors, as The New Yorker reports. It might also be negated by equal but opposite enemy espionage.

After all, the Cold War lasted from right after World War II until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. While things like the Cuban Missile Crisis and mutually assured destruction were no doubt terrifying parts of the era, the Cold War ultimately remained largely cold over all those decades. Is that evidence that espionage works, or that it wasn't all that necessary in the first place? It's hard to tell.

Sometimes, espionage even backfired, Science Magazine reports. A close study of East German industrial spying showed that, while espionage of this sort could help a nation boost its programs in the short term, it had serious long term consequences. Over the years, Communist East Germany began to badly lag behind its capitalist cousin of West Germany when it came to research and development. Investing in more spying did nothing to close the gap.