The Wild True Story About The Origins Of The Oxford English Dictionary

The English language is quite the contradiction. It is equal parts frustrating and fascinating and is as nonsensical as it is logical (see: knight/night or the different pronunciations and meanings of the word "bow"). The origin of the words themselves is where things become even more intriguing, learning about the roots and back story of where the components that make up our everyday conversations come from. But what about the history of the book that collects all of that information?

Yes, a dictionary. Perhaps the last time you cracked one open was many years ago back in school, but its back story and epic journey lives on, as its online iteration serves many people every day. While it may not be something you often consider, dictionaries often have wild and weird stories hiding amongst their pages, and the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is no exception to lore. In fact, it has one of the most fascinating creation stories of all — one that involves murder, mental illness, decades of work, tragic endings, and many, many words in between.

London's Philological Society realized there were no reliable books like this available

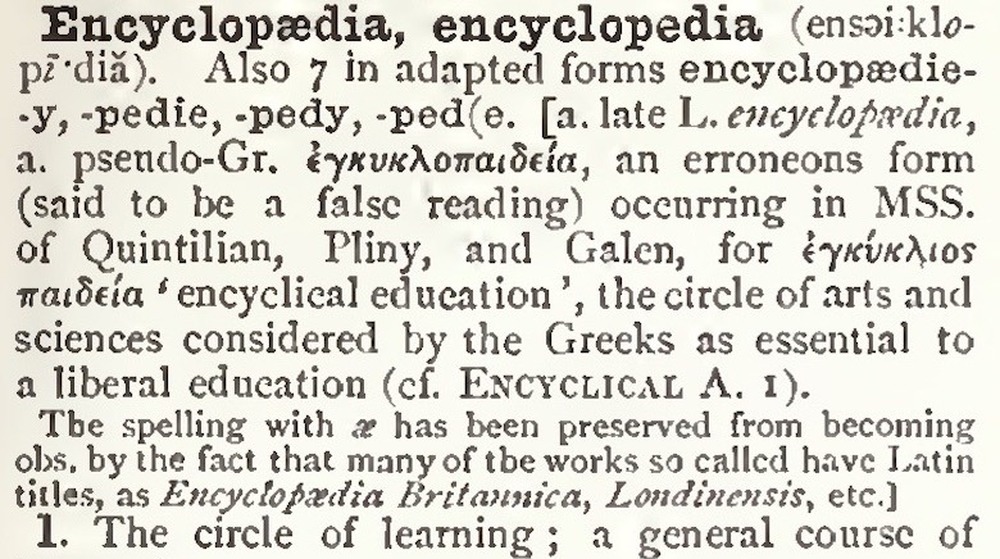

Upon realizing that there were no compilations of English words that were grammatically and historically accurate — as well as relevant for the times — London's Philological Society decided it would start the 70-year journey to making it happen. It would include words from Anglo Saxon times to where they stood presently, which at the time was the 1800s.

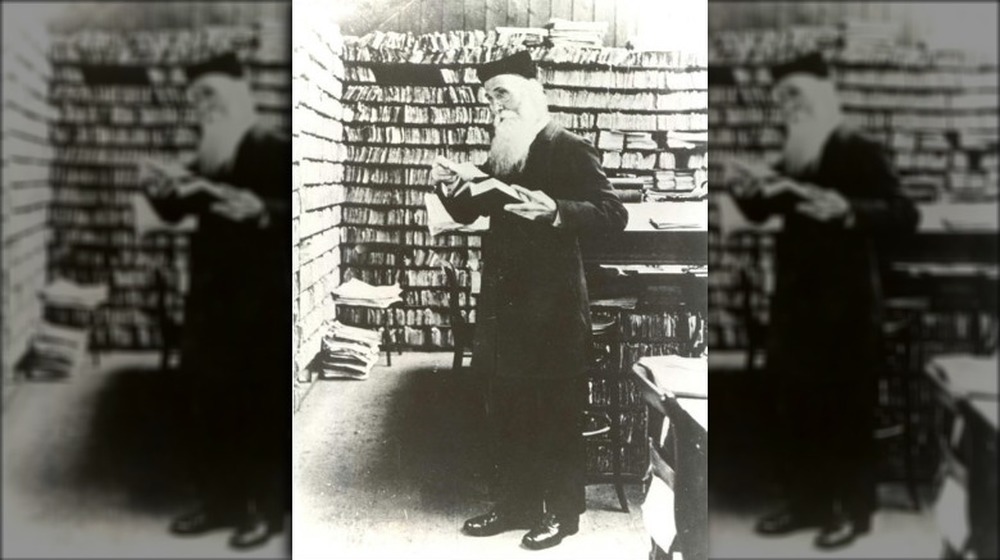

According to The Philological Society, James Augustus Henry Murray was the first official editor of the Philological Society's New English Dictionary on Historical Principles — aka NED. (This was the Oxford English Dictionary's original name, and it didn't receive the title it's known as today until 1933.) Murray was a major figure throughout most of the process and helped make the book the historical living legend it is today.

Sure, dictionaries had been made before, but History explains that what made the OED so different is that it not only provided definitions, but it gave "a detailed chronological history for every word and phrase, citing quotations from a wide range of sources, including classic literature and cookbooks."

It took 27 years for the first part of the Oxford English Dictionary to be published

This exhaustive book was a seven-decade process in total — this was roughly 60 years longer than the Philological Society thought it would initially take. It took an extensive list of people from all walks of life and all across the globe to complete it, including the mayors of small towns in England to government officials from faraway islands, according to History Today. After nearly 30 years, the first "fascicle" was compiled and published, and its first chapters were released in 1884. Unfortunately, as the Philological Society explains, at this point most of the original contributors and editors were dead and unable to celebrate its launch.

While this may not seem like, the project did take a long time after all, many of the surviving members of the society and project began to worry about their futures. Fiona Marshall writes in her article, "The History of the Philological Society: The Early Years," "Aware of his own impending death, [Frederick] Furnivall wrote to Murray following a meeting of the Society in April 1909 expressing his sorrow at having to miss the closing stages of the project. As Murray's friends and colleagues died one by one, he too was left to wonder which would come to an end first, himself or the project." Unfortunately, James Murray too died, 13 years prior to the final installation's release in 1928.

Sir James Augustus Henry Murray was a major player

There were many an editor and leader during the making of the Oxford English Dictionary, but one of the most intellectual and highly motivated was James Augustus Henry Murray. While he was a renowned lexicographer recognized for his massive contributions, there's a common misconception that he was a brilliant scholar who had spent years studying his craft. This is partly true, as he was an incredibly smart man, but his schooling had very little to do with it, according to Pembroke College Oxford.

Just shy of 15, Murray left his modest village school, and that would end up being the last version of formal education he received for a long time. Oxford University Press explains that his natural brilliance helped carry him through life, leading him to several teaching gigs and eventually becoming an avid member of the Philological Society — studying all things words, dialects, and languages on a self-taught basis.

His smarts were only further exemplified upon going back to school to earn a degree from London and then being endowed with an honorary degree from Edinburgh University. He also chose to stay dedicated to his students by teaching while working on the OED, according to Oxford University Press. Eventually, Murray would go on to finish about half of the dictionary himself, says Britannica, an exhausting, but ultimately rewarding accomplishment that featured many interesting characters and experiences along the way.

William Chester Minor was one of the most important volunteers

The bizarre roots and drama that sits behind the OED starts and ends with William Chester Minor. While there may be many secrets and untold truths behind putting together this large compilation, Minor's story is the most widely known. He was an American war physician who was born in Sri Lanka and found himself living in England following the American Civil War, reports the BBC. Minor was smart and quiet, but he suffered from intrusive thoughts that started early in life. Though, it wasn't until later in his career that he developed what seems to have been paranoid schizophrenia, which many believe the war set off.

His life was overtaken by his mental illness, and though he tried to protect himself from night terrors and hallucinations, it all came to a tragic end one evening.

William Chester Minor murdered a man, which led to a connection to the OED

William Chester Minor awoke startled one night to an intruder in his home. To defend himself he ran out of his house to search for the person stalking him in the dark. The sad unfortunate truth was no one had been in Minor's room to begin with, but his brain said otherwise. Spotting a man walking down the street, Minor shot at him several times and killed him.

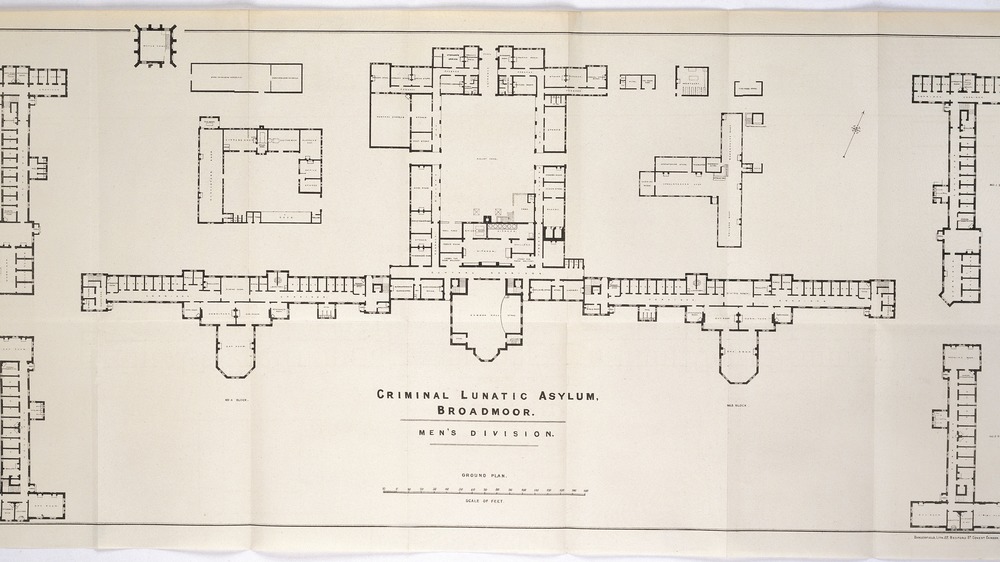

Minor had killed George Merritt (also spelled Merrett in some reports), a man who worked nights at the Red Lion Brewery to help provide for his large family, as per Mental Floss. After a police intervention, and Minor baffled by the fact that he did something wrong, his case was held in court. He was let off the hook under the pretense of old England's version of the mental illness defense but given a life sentence at Broadmoor's Asylum for the Criminally Insane.

While the story is grim, and Merritt's family was left husband-less and father-less, Minor's life sentence eventually led to a small silver lining for him — his involvement with the Oxford English Dictionary.

The victim's wife ended up befriending William Minor and brought him books

Because William Minor sent money to the widow of the man he killed, the two developed an acquaintanceship. She ended up being a frequent visitor, who provided books and conversation to Minor at the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

This budding friendship wasn't the only luxury Minor had while at Broadmoor. The hospital itself wasn't such a bad place to be to begin with. While being locked up, Minor had access to gorgeous views and nature walks, as well as a farm and workshops, which were considered to be more lavish luxuries in comparison to what other mental hospitals at the time provided. According to Psychology Today, patients even seconded the notion that their accommodation at Broadmoor far surpassed that of other prisons and hospitals they had been in. For Minor specifically, he was able to pay a fellow inmate to be his servant and even buy books from sellers outside of the asylum, according to The Los Angeles Times.

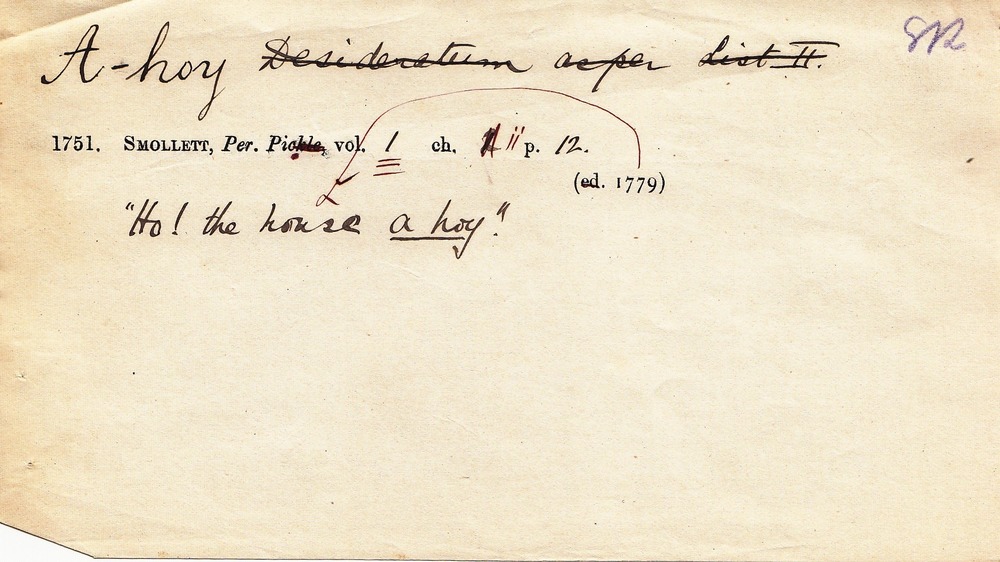

All That's Interesting reports that Minor found the advertisement that the London Philological Society was looking for volunteers in a book and took the opportunity into his own hands from there.

William Minor's history of writing detailed medical records came in handy

William Minor was an army doctor, and not only that but he was trained at the prestigious school of Yale, graduating in 1863. Rather than relying on scribes or other forms of recording or simply memorizing his experiences, he wrote everything down himself and took meticulous notes. Many of his reports are even available to read to this day. Yale Medicine Magazine explains he wrote papers on everything from worms that could rebuild themselves to the minute details of diseases he found in doing autopsies. This knack for accuracy and writing gave him an advantage when it came to helping create the dictionary verbiage.

Being stuck in a mental hospital and having a very revered background, Minor was a perfect candidate for providing definitions and etymologies. He would spend days sifting through the pages of books then "mailing the editors vast numbers of quotations demonstrating the words' meanings and early appearances in English literature." What started as a project to keep him busy turned Minor into a respected contributor to members of the Philological Society.

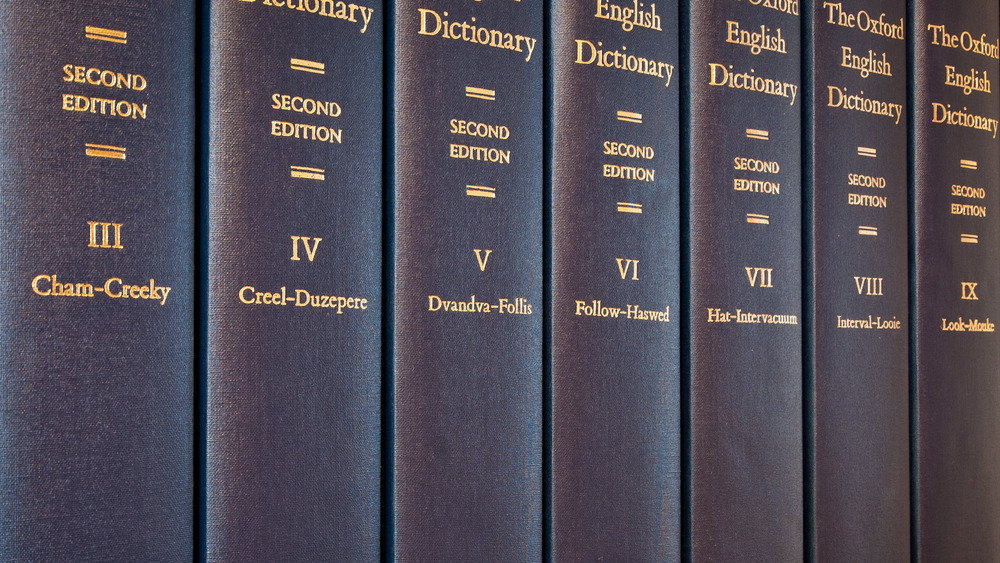

The first dictionary included 400,000 definitions and was 15,490 pages long

What was originally meant to be a decade-long project ended up taking far longer, and in actuality, the end date never really came about since the dictionary is still updated to this day. The first edition was considered to be just one "fascicle," and it was printed in 1844. Over the years, more installation were created, and the last volume was finally released in 1928. Jenkins Law Library explains that updated versions, corrections, and revisions were continually created over time, with another "supplement" of it appearing in 1933.

Not only was the length of time predicted utterly wrong, but the actual size of the dictionary was also inaccurately assumed. BBC says that the plan was a book of 6,000-plus pages, but at the time of print in 1928, the text was a shocking 15,490 pages long. This was all possible thanks to the help of William Minor and other notable helpers, says the Oxford English Dictionary, including Philological Society member Frederick James Furnivall, historian Edith Thompson, author J.R.R. Tolkien, and countless other volunteers across the globe who answered the call for contributions to the esteemed dictionary.

James Murray came to visit William Minor, having no idea who he really was

After William Minor's dedication to the dictionary project, editor James Murray began to grow fond of the astute volunteer. Murray assumed Minor was a high-ranking individual working at Broadmoor — he had no idea he was actually a patient. Murray arranged to visit Minor, learning from a librarian that he wasn't quite the man he assumed. The New York Times writes, "On a visit to England, the librarian of Harvard College thanked Murray for being so kind to ”our poor Dr. Minor,” which confused Murray. Still, after finding out the truth and officially meeting him, Murray's respect grew for Minor.

Despite their lives being so starkly different, Murray no doubt was thankful for the two decades Minor spent sending in his slips of paper he researched and wrote for the dictionary. This appreciation for Minor was so deep that Murray even became one of the biggest proponents for petitioning against Minor's sentence and demanding to have him released. Several years later, this eventually happened.

William Minor had a tragic end to his life, but his contributions live on

Sadly, William Minor's condition only worsened as years went on. His awful hallucinations, delusions, and nightmares continued to get darker. After suffering through a particularly horrific bout of thoughts having to do with assault — which he never acted on — Minor resorted to castrating himself (via Owlcation). Following this, in 1910, Minor was finally removed from Broadmoor thanks to James Murray's advocacy and a pardon from Winston Churchill.

Minor was brought back to America, where he received more medical attention and his ultimate diagnoses of schizophrenia. There are conflicting stories, but it is said that Minor eventually died in the early 1920s, either at an institution specifically catered to elderly patients dealing with mental illness or in his own home. But even after his death, the work he did for the Oxford English Dictionary, and even the Webster Dictionary, helped lay the foundation for where both books are today.

William Minor's contributions to the Oxford English Dictionary were unprecedented

In 1899, James Murray commended William Minor on his countless contributions, saying Minor had gathered roughly 12,000 quotes for the project in just two years, all hand-written and sent in by mail to Murray and his team. Since the dictionary spanned so many decades, Minor chose to specifically focus on 16th and 17th century quotations for his work, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. It was said that without his help, 400 years worth of entries would be absent.

While Oxford was his big break in the world of word compilation, The Nation explains that definitions weren't something he helped with — but rather quotations. This means he wasn't responsible for the exact meaning of the words but instead helped with the context and relevancy of them. Minor's defining skills came in handy prior to the OED, when he helped with another major project, which you now may know today as the Webster Dictionary. The Nation writes that this came before his Oxford volunteering days, but because of the major mistakes and errors he made for Webster, it is not talked about or celebrated nearly as much as his contributions later in life.

Where the Oxford English Dictionary stands now

What started as an immense large-scale project has only grown bigger. And now, rather than simply materializing in the form of a massive textbook, there is an online version. The web edition sees updates nearly every 90 days, says the BBC, and words that are more commonly found in the modern-day English vocabulary can be found. For example, in 2020, the words "adulting" and "follically challenged" were added. This is much to the assumed dismay of the 1928 editors of the OED that once told The New York Times in reference to more laid-back vernacular, "No doubt many of these might be described as slang, but they have a way of rising out of this character and taking their place in serious discourse and writing."

The print edition on the other hand gets updates in much longer intervals. While a rumor was started that the print edition was going to be axed, the spokesperson for Oxford Press denied the claims and said that the third edition was actually in the works back in 2010, and it was a little under a third of the way being done. This new edition has yet to be released (there has only been two before it to give you an idea of the efforts it takes to revise), with the reasoning behind the lengthy process being that the entire book is being fully revisited — the first time since James Murray, William Minor, and others ran the show, according to OED.