Famous People Who Survived The 1918 Flu Pandemic

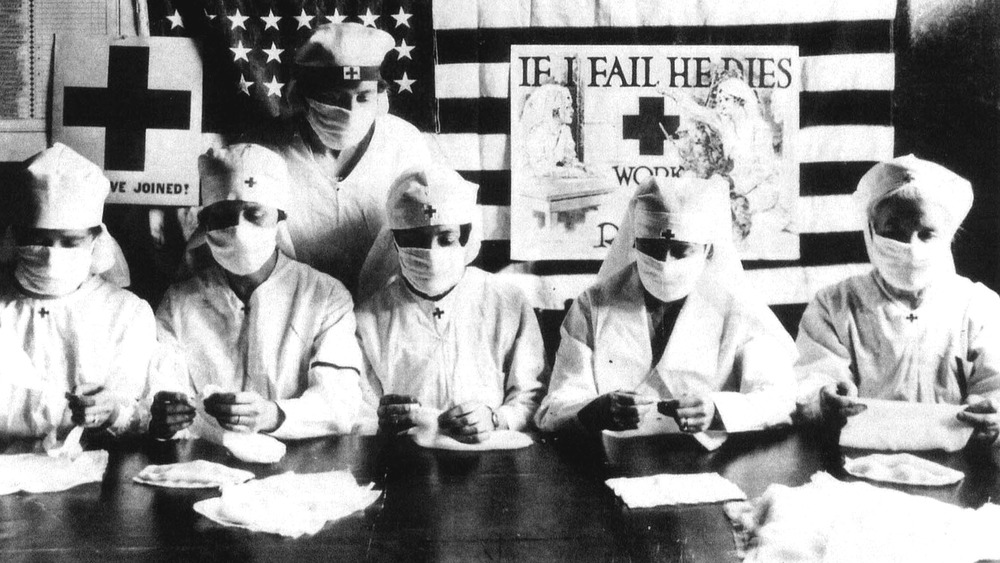

Some strange things happen when there's a global pandemic, and first is the loss of normalcy. It doesn't take long to forget what it was like to run to the store without a mask or get together with friends without having to sit six feet apart... and yell the personal details of whatever conversation you're having. Pandemics are nothing new, and they've happened a lot. That's scary, but it should also give us hope – they do come to an end.

One of the most devastating was the post-World War I Spanish flu, which killed somewhere (according to most estimates) between 20 and 50 million people. To put that in perspective, that 50 million number is — strangely — about the entire population of Spain. On the low end, 20 million is about the population of Chile (via Nations Online).

And it was horrible stuff. One nurse described dealing with the dead like this (via The New Statesman), "When their lungs collapsed, air was trapped beneath their skin. As we rolled the dead in winding sheets, their bodies crackled — an awful crackling noise that sounded like Rice Krispies when you pour milk over them."

That's an almost unthinkable amount of illness, death, and grieving, but not everyone who contracted Spanish flu died from it. Some survived, and some of those survivors were incredibly famous people.

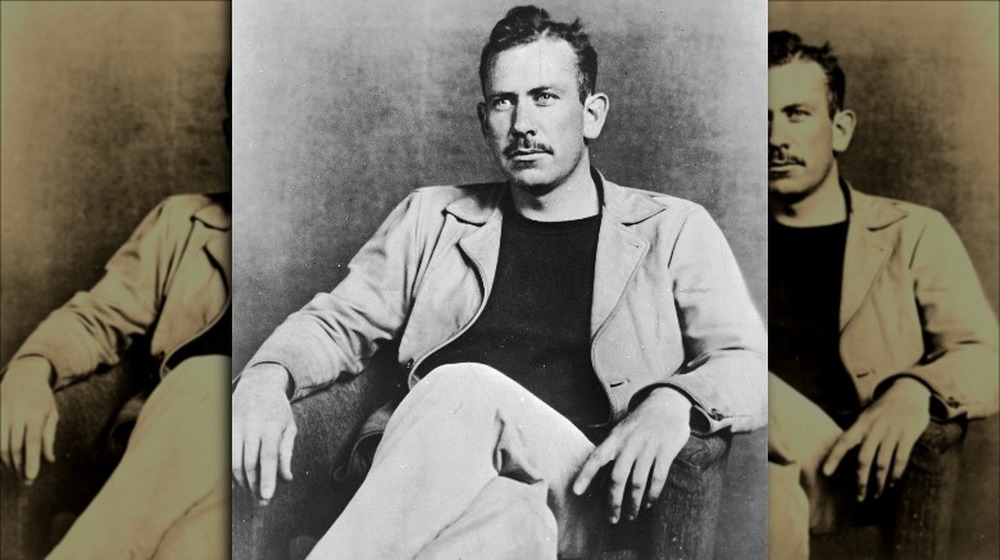

One of America's most beloved authors

John Steinbeck's novels — especially Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath — are on every high school reading list, and it's no wonder. They capture bygone America and Americans who are often overlooked when it comes to chronicling their lives. But those works came close to not happening.

Steinbeck was 16 years old in 1918, and according to Biography, he already knew that he wanted to be a writer. But it's the best laid plans of mice and men, as they say, that often go awry — and Steinbeck didn't just contract Spanish flu, he nearly died from it. According to The New Statesman, his case was so bad that his infected lung had filled with fluid, and in order for a local doctor to get in and drain it, he needed to have a rib removed. (It was one in a series of health-related problems, and The Independent adds that the following year, he had his appendix removed, too.)

Steinbeck survived, of course, but The Mercury News says his missing rib gave him grief for the rest of his life. Always the writer, he would later recall the experience, "I went down and down, until the wingtips of angels brushed my eyes."

There was nearly no Mickey Mouse

Anyone who has any doubts about the impact they might have on the world should remember the nameless man who sent a young ambulance driver named Walt Disney home to recover from a bout of Spanish flu.

Disney, says Mouseplanet, had convinced his parents to let him join the Red Cross's American Ambulance Corps, changed his age on his documentation, and headed off to Camp Scott near Chicago. He was there when Spanish flu swept through the facility, and the powers-that-be sent him home.

Disney was deathly ill at the time, and here's the thing — they sent him home instead of keeping him in the hospital because the death rate was already high, and they had more patients than they could handle. Several of his friends had already died in hospital care, and Disney later recalled, "One guy said to me, ... 'Can we take you home. You've got a better chance at home. If we take you to the hospital, you may never come out.' And I said, 'Yes, you can take me home.'"

So they did — on a stretcher. Disney's mother nursed him back to health (also catching and recovering from the flu, along with his sister Ruth). By the time he was back on his feet and well enough to return to active duty, Armistice had been signed.

Two of the most popular film stars of the era

At the time Spanish flu was working its way across the globe in a deadly, relentless advance, the Women Film Pioneers Project says that Mary Pickford (right) and Lillian Gish (left) were two of the biggest film stars in the world. When they came down with Spanish flu, film historian William Mann says (via Deadline) that at the time, their illnesses — along with the closure of places like movie theaters — changed the industry.

Not only did it spell the end of mom-and-pop style theaters, but it also changed the way movie companies were organized and laid the groundwork for today's industry. Hollywood, says Mann, was particularly hard hit by the consequences of Spanish flu in part thanks to male movie stars who refused to wear masks because "they wanted to appear manly and masculine."

It didn't necessarily work. Another incredibly popular star, Harold Lockwood, didn't survive — he died within days of coming down with Spanish flu. The California Express reported that when Mary came down with the flu, she was rushed to the hospital alongside her equally famous brother, Jack Pickford. Jack's stay required an operation, but ultimately, he, Mary, and Gish all survived.

Interestingly, Movies Silently says Mary Pickford's 1919 film Daddy Long Legs features a blink-and-you'll-miss-it nod to Spanish flu. The actress is on the crowded platform of a train station when she sneezes and causes mass panic.

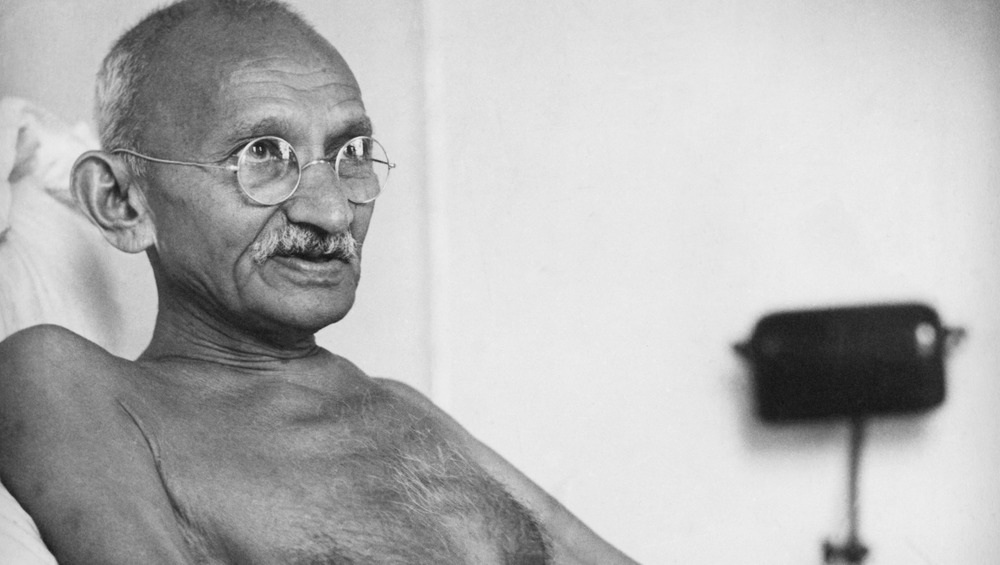

India's most devoted champion

According to the BBC, the Spanish flu traveled to India on board a military transport ship that had docked in what's now Mumbai in June of 1918. It wasn't long before it spread across the country, and it's really no wonder, considering the advice published in The Times of India was "go to bed and not worry."

Mahatma Gandhi was living in an ashram in western India when he came down with the flu, and based on what he wrote in letters to his family (via The Siasat Daily), it was a severe case. In August, he wrote in two separate letters that he was "too weak to get up or walk" and wondered in another, "Perhaps this will be my deliverance."

Gandhi thought the Spanish flu was penance, delivered by a divine being who was angry at the world for having strayed so far — specifically, the Rachel Carson Center says that he believed it was a divine condemnation of colonialism. Not everyone agreed with him, and The Times of India says that wasn't the only clash he had during his illness. He also refused to obey a large portion of his doctors' orders, because they involved things — like drinking milk — that he was against. He did, ultimately, give in on some of his protests and recovered — unlike his daughter-in-law and grandson, who both died from the flu.

The man behind the bomb

Leo Szilard might not be a household name, but without him, it's undeniable that our world — and our world's history — would be a very different place, indeed.

Szilard was born in Budapest, and by the time World War I rolled around, he was just the right age to be drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army. That didn't happen, says the Atomic Heritage Foundation, because he came down with a nasty bout of Spanish flu that took him out of the running for active duty.

He survived, and after the war, he ended up heading to Berlin to finish his schooling. From there, the Jewish Virtual Library says he partnered with Albert Einstein on multiple projects, like a patented a refrigeration system that would later become the basis for the atomic reactor. And in 1933, after moving to England, Szilard came up with the idea for the nuclear chain reaction.

Szilard wasn't just a genius, he was incredibly practical, too. He moved to New York in 1940 and became involved with the United State's nuclear weapons programs, but he did something else incredibly important — he insisted that all of the program's research be classified, and that nothing should be published until after the war. As unhappy as he was about the military applications of the nuclear reactors he helped build, he was instrumental in the development of the atomic bomb — and in the policies that kept tech and research from reaching back to Germany.

America's most famous pilot

Amelia Earhart's life story has it all, from breaking through the glass ceiling to becoming a world-famous female pilot to a mysterious disappearance that stunned fans around the globe. She wasn't always going to be a pilot, through, and according to Sky History, she first trained as a nurse.

As soldiers began to return from the war, Earhart (and her sister, Grace) helped the war effort by volunteering for the Red Cross. While she wasn't originally involved in the medical side of things, she did cook and handed out meals and medicine to the wounded men.

That was in 1917, and it was the following year that she contracted the Spanish flu and spent much of November and December in the hospital. History Collection says that not only did she get Spanish flu, but that it turned into pneumonia that was so severe that she needed to undergo surgery for her sinuses. The result was a lifelong struggle with chronic sinusitis, which could get so bad that it sometimes necessitated the wearing of a drainage tube. (In photos where she has a bandage on her face, she's covering the tube.)

Earhart recovered and initially intended on continuing her medical training to become a nurse. A 1920, 10-minute flight — a gift from her father — changed that, and the rest is, as they say, history.

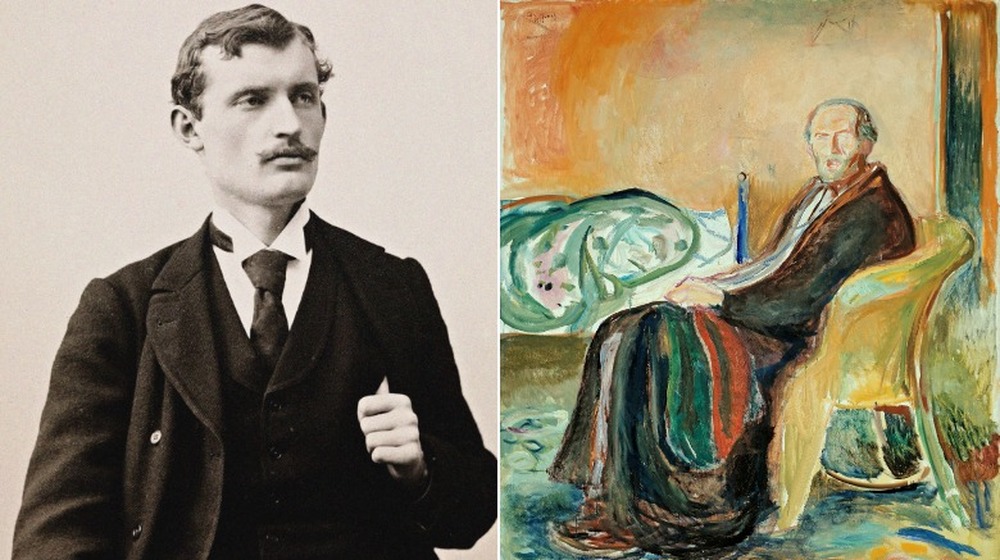

Dorm room walls just wouldn't be the same

Artnet says there's a strange phenomenon surrounding the Spanish flu — in spite of the fact that it was so widespread and so deadly, there's not many depictions of it in contemporary art.

They suggest that's in part because artists were preoccupied with the war. But there's one major artist who not only depicted the Spanish flu in his work, he survived it — Edvard Munch.

He's more well-known as the artist behind The Scream, but he's a wildly prolific artist who also painted Self-Portrait With the Spanish Flu (pictured) and Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu. In the first, he's clearly sitting in a chair beside a messy bed, a silent scream on his face, and in the latter, he's back on his feet but clearly haunted.

Daily Art Magazine says that Munch's art drew immediately from the illnesses he'd suffered his entire life and adds that his official diagnosis was neurasthenia (which Science Direct says is characterized by fatigue after mental or physical exertion), which is often accompanied by hypochondria. To fall ill with a deadly disease had to be terrifying, and it's reflected in his work, and his writing — he once said (via Time), "Illness, insanity, and death... kept watch over my cradle, and accompanied me all my life."

Delving into the wasteland

T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land was published four years after the Spanish flu made an appearance on the world stage, and he wrote much of the work while he was recovering from the illness.

According to The National Herald India, that's reflected in countless lines, like, "He who was living is now dead, We who were living are now dying, With a little patience."

Both Eliot and his wife got sick with the Spanish flu, and even though her case was much, much worse, the Richmond School of Arts and Sciences says that they were convinced it had permanently changed them both. As for his wife, Viviene, he wrote in a letter that it "affected her nerves so that she can hardly sleep at all," while they believed it had impacted his brain in other ways. It was his wife who later wrote some frightening things in her correspondence, saying that "his mind is not acting as it used to do."

Read through that lens — the terror and certainty of illness that leads, ultimately, to death — The Waste Land is a terrifyingly relevant piece of literature in the wake of any pandemic.

I saw, and behold, a pale horse

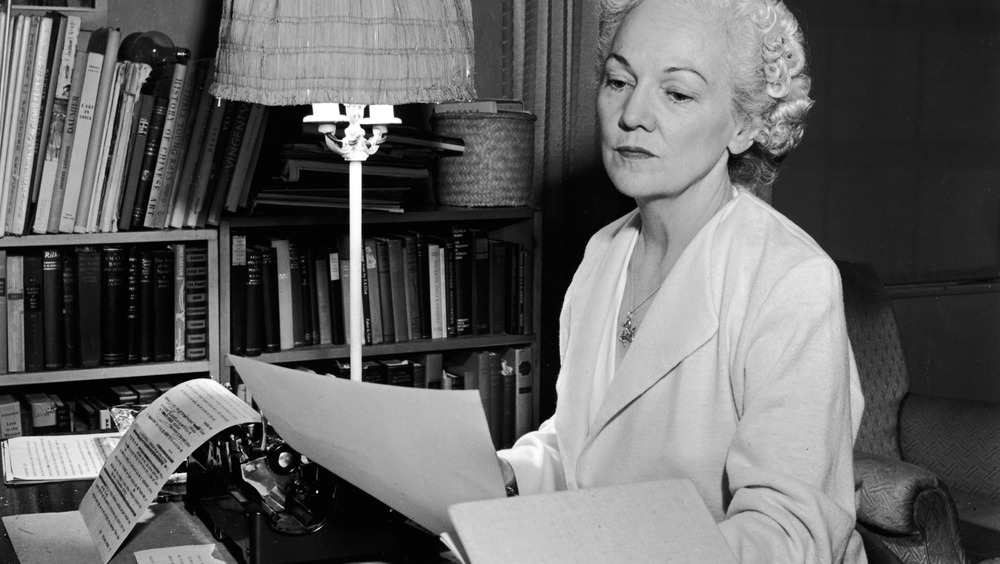

The novel, Pale Horse, Pale Rider, tells the tale of 1918-era America — complete with the loss from war wrapped up into the loss from an unthinkable pandemic — with shocking and surreal clarity. That's in part because the author, Katherine Anne Porter, nearly succumbed to Spanish flu herself.

The University of Maryland Libraries says that Porter got sick in October of 1918, just three years after having been diagnosed with tuberculosis. After being hospitalized for some time, she moved to Colorado because of a climate that was more favorable than her native Texas, and it was in Colorado that she came down with the flu, just weeks after Denver's first recorded death.

Denver had so many cases that it took help from the doctor who had treated her for her tuberculosis to find room for her at one of the city's hospitals, and her health deteriorated so quickly her family even started making funeral arrangements. She would later describe it, "I was just dying, and people were dying all around me, everywhere. ... they'd given me all the attention they could."

Then, two interns gave her a shot that was either camphor oil or strychnine (there's a few different versions of the story), and she credits it with saving her life. She had a long and painful recovery marked by broken bones and baldness. When her previously black hair started to grow back, she found that at 28 years old, she had gone salt-and-pepper.

"Ordinary influenza by another name"

Woodrow Wilson was president when the Spanish flu descended on a world's population that was already reeling from a global conflict, and according to experts, he absolutely made it worse. Author and historian John M. Barry says (via CNN), "So to keep morale up, ... the government lied. ... National public health leaders said things like, 'This is ordinary influenza by another name.' They tried to minimize it. As a result, more people died than would have otherwise."

Wilson was in Paris when he succumbed to the flu, and it was so bad that at first, his doctors didn't even recognize it. Amid his hallucinations that he was being followed by spies and the furniture in his room was moving, doctors briefly suspected that there really had been an assassination attempt, and that someone had dosed him with poison.

Even as he struggled to survive the potentially deadly illness, the public was told that he'd come down with a bit of a cold, but that everything was a-okay (via Smithsonian). Everything was not a-okay, and those closest to him noted that "something queer was happening in his mind," and that he "was never the same."

And Wilson's bout of Spanish flu may have had far-reaching consequences — instead of actively participating in the peace treaty, he simply agreed... to incredibly harsh terms for Germany and a treaty that was credited for adding fuel to the fire that started World War II.

"It's not regarded as serious..."

The National Archives says that when future president and then-Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Delano Roosevelt came down with a case of Spanish flu, the nation was — perhaps predictably — lied to about it. Even as they were told his illness was "not regarded as serious," FDR wasn't just fighting the flu, he was fighting double pneumonia. (And that, says Healthline, is pneumonia that infects both lungs, instead of just one.)

FDR had been traveling across Europe inspecting U.S. troops, and it was on his return in late 1918 on the USS Leviathan that he — and many others on board — got sick. He was so sick, in fact, that he was unable to walk off the ship under his own power and needed to be carried. FDR recovered (and contracted polio just three years later), but it's entirely possible that neither of those ended up being a bad thing... historically speaking.

When USA Today polled historians to see which president they thought would be best equipped to deal with the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, FDR was a favorite — and not just because he saw the country through the Great Depression. Historian Douglas Brinkley put it this way, "He really understood how a virus could attack a human body." That understanding — coupled with his optimism, trustworthiness, and his ability to get people to volunteer for the greater good — made him one of history's favorites.

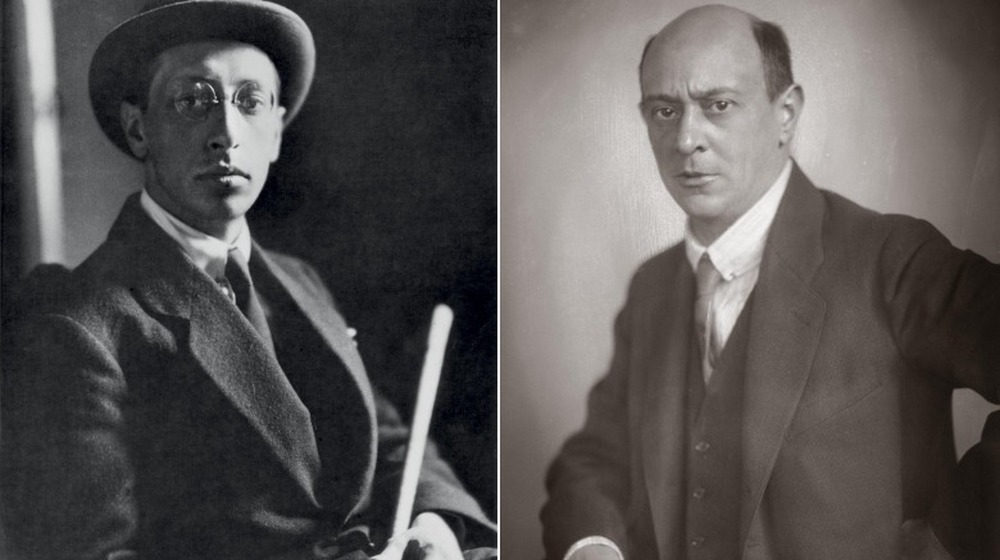

Changing the sound of classical music

Several of the era's most famous composers caught the Spanish flu and survived — then went on to change just what classical music was and meant.

Igor Stravinsky (right) went into lockdown after the cancellation of his concert tour. It was October of 1918, L'Histoire du Soldat was on hold, and his son would later write about how (via Brian Wise) his father was unable to do anything but lay in bed with his eyes covered. Nursed by his wife, he recovered.

Sergei Rachmaninoff also contracted the Spanish flu, and — still sick — left confinement to practice for an upcoming tour.

Then, there's Arnold Schoenberg (left) — who suffered from asthma bad enough that it got him discharged from active duty in the military. He was up close and personal with the flu for much of his life. In addition to losing his father to it (in 1890), he had it several times a year for more than a decade — and that included the Spanish flu (via The Irish Times). While they add that his physical illnesses didn't show up illustrated in his music until he developed a heart condition, DW does note that it was around this time that he created a new system of music that was based on 12 tones. That's one way to use the most of time in lockdown!