The Crazy Real-Life Story Of The Transcontinental Railroad

Imagine the days before planes, trains, and automobiles. As 21st-century humans, it's hard to conceptualize relying on the Pony Express to deliver our snail mail, let alone our Amazon deliveries. These days, people are used to instant gratification, where the latest impulse purchase arrives overnight, starting out on one coast in the evening and taking the red-eye to land on the opposite coast by morning.

The First Transcontinental Railroad, which was in direct congruence with the Industrial Revolution, wasn't the first rail line in America, but it was certainly the most ambitious. And upon completion, it forever altered the shape of both business and pleasure by finally providing a feasible means of transportation from east to west. The railroad was so ambitious, in fact, that it took multiple investors, permission and aid from the government, hundreds of engineers, and thousands of laborers who braved harsh weather conditions, and unethical treatment, to complete it.

There is no doubt that significant progress was made in America in terms of trade, further financial development, and, most importantly, "westward expansion," according to the History Channel. But progress is never made without sacrifice. The story of the conception of the Transcontinental Railroad is filled with cases of corruption and crimes against humanity. In some ways, its very existence is a representation of the Industrial Revolution itself. Read on to get the truth behind this epic undertaking of man and machine.

Who came up with the idea and why?

The steam locomotive came to America in 1830, and by the 1840s, there was a real desire for a railroad route that would link the United States from east to west. Around this time, American settlers were beginning to move west in droves, mainly due to promises of striking it rich in the California Gold Rush. Because the journey was dangerous, some even took a six-month-long trip by sea to San Francisco to avoid tricky terrain.

New York businessman Asa Whitney proposed a federal funding resolution to Congress in 1845, which would allow for a railroad to reach the Pacific, but it was unsuccessful. Throughout the 1850s, Congress sponsored a handful of survey parties to investigate where the route made the most sense, but no consensus was ever reached, according to the Linda Hall Library. In 1860, however, engineer Theodore Judah's proposal to construct a railroad that would move through the Sierra Nevada mountains would prove more palatable.

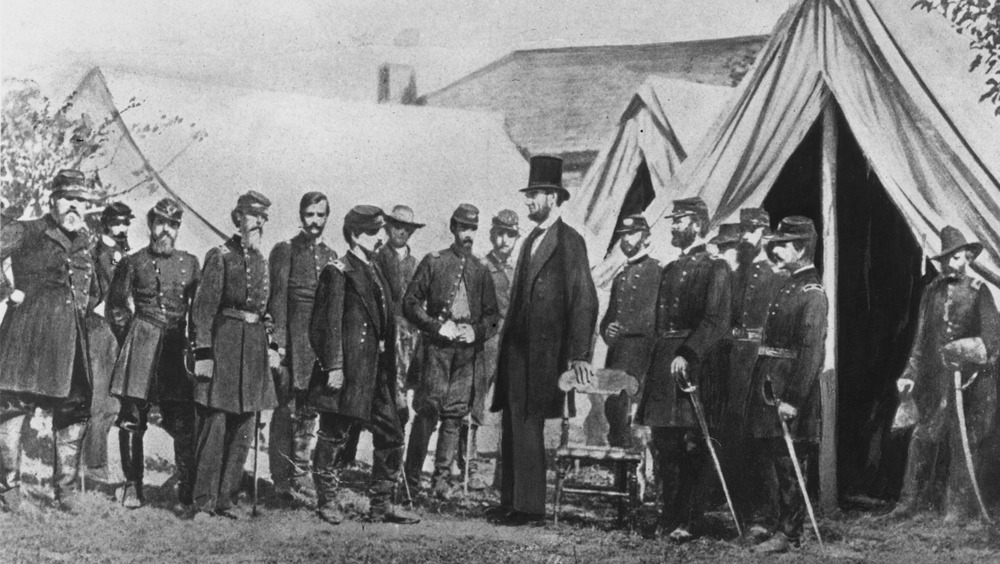

In 1861, Judah was able to convince Congress, as well as then-President Abraham Lincoln, to get on board with his plans.

When was the plan enacted?

Thanks to Theodore Judah's efforts, the Transcontinental Railroad was finally officially commissioned by President Lincoln with the enactment of the Pacific Railway Act of 1862. According to the official Union Pacific website dedicated to the railroad's 150th anniversary, the legislation allotted two rail lines 6,400 acres each, including up to $48,000 in government bonds to assist in the colossal undertaking.

The two railroads charted for the project — the Central Pacific Railroad of California, which was permitted to build a line east from Sacramento, and the Union Pacific Railroad Company, which would build west from the Missouri River — immediately began a race to the finish. Luckily, the acquisition of California after the Mexican War paved the way for routes to the West Coast.

The Central Pacific Railroad had already gotten a head start in 1861 but was officially authorized a year later. Judah's interests lied in the West, where he recruited a few rising businessmen to finance the project. None of these businessmen had prior experience in investing in either engineering or construction. The Union Pacific line did not launch until near the end of 1863.

Who funded the Transcontinental Railroad?

While leaders of both railroad companies lobbied for government aid, they didn't receive full funding. Although government bonds certainly helped, the project was ultimately funded by three private companies, as well as company-issued mortgage bonds.

The Transcontinental Railroad was certainly considered the greatest construction project of the century, and the government provided a land grant, which was only a piece of the puzzle. Before the railroad could be built, the land had to be sold, which proved difficult because not only did the land have to be surveyed, but the government land office became overwhelmed with patents to issue, according to The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

Once the land was settled, the financial investors of both rail lines also became concerned about the lack of profitability of sitting land on unsettled country. Since the patents took so long, construction wouldn't be able to start immediately after the land purchase. Construction, not the railroad itself, was how these financiers planned to make their money.

Ultimately, the railroad lines would not have gotten made without four men.

The Big Four

Before the Transcontinental Railroad was built, California was isolated from its fellow states. Theodore Judah made it his mission to get enough funding so that California had more access, and that states had more access to California. Enter the "Big Four," the four financial backers who made Judah's dream possible.

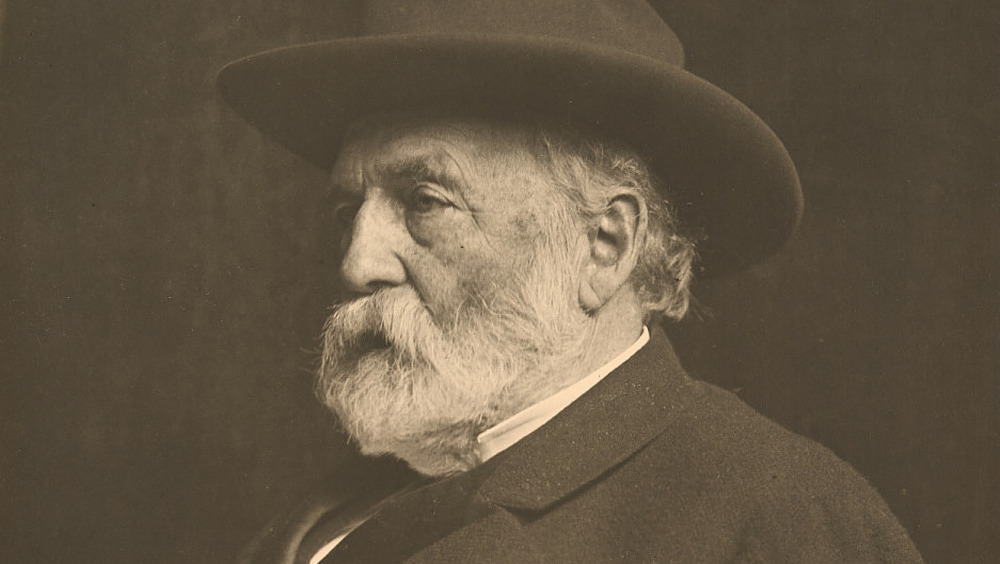

Collis Potter Huntington (pictured above), who oversaw construction of the western portion of the project, came to California in search of gold in 1849. He was known for pushing the Central Pacific line workers to the breaking point in the hope that their project would be completed before Union Pacific's. The other three financiers were Leland Stanford, a California senator for whom Stanford University is named, Mark Hopkins, a California capitalist for whom San Francisco's Mark Hopkins Hotel is named, and Charles Crocker, a businessman, banker, and chief contractor of the Central Pacific line.

According to a San Francisco Chronicle review of the book The Associates: Four Capitalists Who Created California by Richard Rayner, the Big Four were commonly thought of as "robber baron-protagonists" because they engaged in a number of unethical business practices to reach their ends. Not only did they exploit labor, but they committed financial fraud by manipulating governmental funds and often employed corrupt tactics to crush their competitors.

Central vs. Union

The Central Pacific Railroad of California and the Union Pacific Railroad Company were highly competitive with one another.

Theodore Judah, Central Pacific's chief engineer, had California's interest at the forefront of his plans, whereas Thomas C. Durant of Union Pacific advocated for expansion in the Midwest. Central Pacific built 690 miles of track along incredibly difficult terrain in the West. The line constructed 15 tunnels through the Sierra Mountains, according to Union Pacific's 150th Anniversary page.

The Union Pacific line broke ground in 1863 in Omaha, Nebraska, specifically avoiding building a bridge over the Missouri River. Doing so would have been costly, not to mention a lengthy process, and Union Pacific's engineers were scrambling to catch up with Central Pacific's line, which had begun construction two years prior. General manager Durant lobbied for the route to start in Nebraska and not in Council Bluffs, Iowa, as President Lincoln had originally declared. By 1869, builders had successfully laid 1,086 miles of track from Omaha, through Wyoming, and into Utah. The line included eight bridges and four tunnels.

Both lines eventually met in Utah upon completion.

Building the Transcontinental Railroad

It was no small feat to complete a project as ambitious in scale as the Transcontinental Railroad. By 1863, both the Central Pacific and Union Pacific lines had broken ground. The Central Pacific team once managed to lay ten miles of track in one day, and the total number of track miles laid by both companies accumulated to 1,776 by the end.

But the Transcontinental Railroad would take nearly a decade to finish thanks to harsh working conditions, including temperamental and even dangerous weather, which slowed the projects down considerably. In fact, the Gilder Lehrman Institute reports that it got so cold that the Central Pacific line built 40 miles of snow sheds in order to avoid blizzards and be able to continue working on the tracks.

The tracks reached an impressive altitude of 7,017 feet above sea level at the Summit Tunnel on the Central Pacific Line, and 8,242 above at Sherman Pass on the Union Pacific line. By the end of both projects, over 21,000 laborers had been hired to lay the tracks.

Trade and profit

It was no picnic building the Transcontinental Railroad. The weather alone made production difficult, with harsh winters, sweltering summer heat, and the Wild West still experiencing a fair share of lawlessness. Many workers even froze to death, their bodies buried in the snow, some never to be found. All of the blood, sweat, and tears were extremely profitable, however. By 1868, the Transcontinental Railroad had made at least $23 million in profit for Crédit Mobilier investors, a 280% return on investment.

The railroad made transporting goods from coast to coast much easier, causing a massive business boom from Western food crops to manufactured goods and raw materials. According to the History Channel, by 1880, it's estimated that the Transcontinental Railroad transported $50 million worth of freight per year. The railroad would also begin to facilitate international trade.

Not only did the building of the railroad create a capitalist boom in America, but it changed the way Americans lived, and where. Around 7,000 cities and towns popped up across the country as depots and water stops for the Union Pacific line across the Midwest.

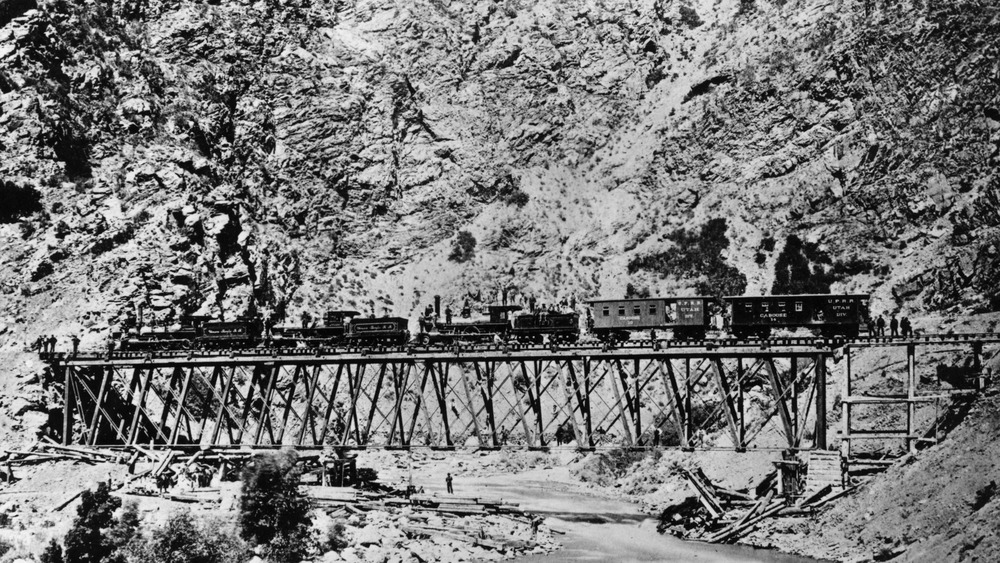

Building bridges and tunnels

Completing the Transcontinental Railroad involved digging a total of 19 tunnels, which was far from easy in the 1860s. Excavation involved picking away at stubborn granite with hammers and chisels. This equated to completing only one foot per day. The rate increased to two feet per day when laborers began using nitroglycerine to get through the stubborn rock.

Constructing tunnels was a lengthy and arduous process, but it allowed for a much more direct route between coasts. The Summit Tunnel on the Central Pacific line alone required laborers to cut through 1,750 feet of granite, according to the Linda Hall Library. Ultimately, the tunnels made a huge difference in how fast the railroad could cut through vast, undeveloped, and wild landscapes.

Special bridges also had to be built since existing ones could not withstand the weight of a railroad locomotive. Bridge frames called trusses assisted in bracing the weight of the train. Both lines patented truss designs, generally made from a combination of metal and wood. Both railroad companies also built a series of temporary bridges that would be replaced down the line with a more secure iron structure.

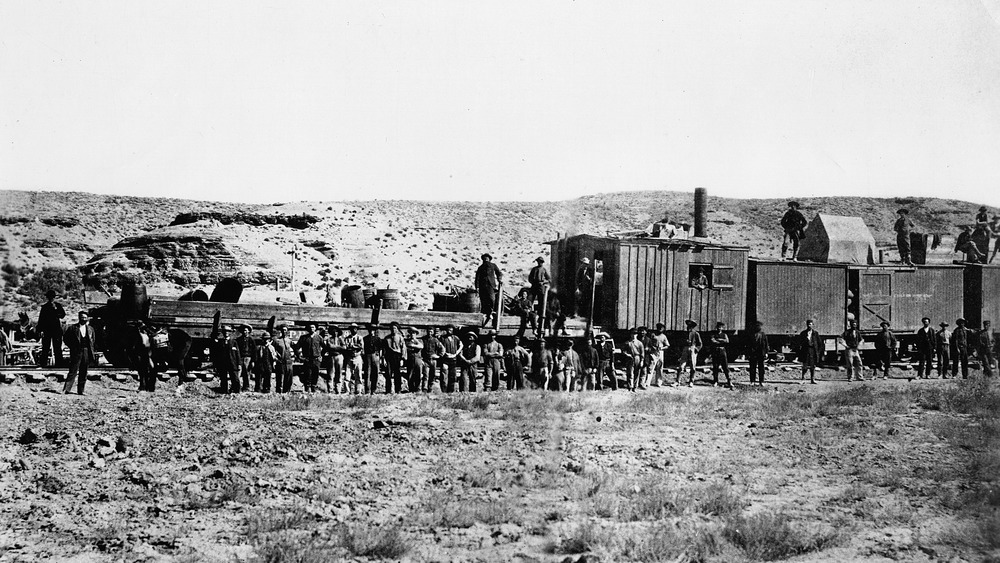

Who built the Transcontinental Railroad?

Many of the workers who built the Union Pacific Railroad were Civil War veterans of Irish descent, and the overwhelming majority of the Central Pacific Railroad workers were Chinese immigrants. Conditions were not only brutal, but workers were expected to work 12-hour workdays while laying tracks over the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Sometimes, men would die, caught in an accidental explosion or even an avalanche.

Chinese immigrants were building railroads in California prior to the Transcontinental Railroad. When more work became available with the Central Pacific line, immigrants were recruited in droves from the Guangdong province in China, according to the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University. This was due to the fact that recruiting white workers had proved largely unsuccessful — it was no secret that the labor required was hazardous. Leland Stanford, who built his wealth off the backs of Chinese immigrants, told Congress in 1865 that, "A large majority of the white laboring class on the Pacific Coast find most profitable and congenial employment in mining and agricultural pursuits, than in railroad work." It is estimated that 10,000 to 15,000 Chinese immigrants worked on the Central Pacific line.

The Union Pacific line was mainly built by Irish-American war veterans. Historical timing was perfect, given that nearly a quarter of Ireland's population had fled due to the Potato Famine of 1845-1852, and, much like Chinese immigrants, the Irish didn't have the luxury of being choosy when it came to employment.

The Transcontinental Railroad's route

The Transcontinental Railroad's two end points were Sacramento and Omaha. The two railroad lines would eventually meet in Promontory Point, Utah, and the railroad was officially completed on May 10, 1869. By comparison, a historical map courtesy of Stanford University shows the railroad plan in 1855, which would have gone from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Coast.

As the railroad popped up through the Midwest, communities commonly known as Hell on Wheels towns formed near its tracks. These towns got that name because they were mainly known for saloons, brothels, and gambling. People lived in "canvas tents, plain board shanties, and turf-hovels," according to Samuel Bowles' writings. The route also created tension among the Native American communities that resided where construction workers and freshly settled residents emigrated to. Unfortunately, due to tensions and fights over land, many members of the Sioux and Arapahoe tribes were killed.

Some disturbing documentation of the period from members of the U.S. Army gives us a glimpse of how apathetic many in power were to eliminating tribe members. In 1867, General William Tecumseh Sherman wrote, "The more we can kill this year, the less will have to be killed the next year, for the more I see of these Indians the more convinced I am that they all have to be killed or be maintained as a species of paupers."

Passengers and profits

Before the Transcontinental Railroad was built, it cost $1,000 to travel across the country, which would equate to around $30,000 today. So, basically, fewer than one percent of Americans could afford it. Not only was the price out of reach, but it took several months to venture from coast to coast.

After the railroad was built, the cost went down to $136 per ticket to take a seven-day journey from New York to San Francisco, which was still pricey but opened up the option to a slew of possible customers. And that was for a first-class ticket in a Pullman sleeping car. If you wanted to travel second-class, it would cost you $110, and third- (or emigrant-) class seats were only $65 a ticket.

Who profited from ticket sales? One of the most infamous financial scandals of the 19th century was born from the Transcontinental Railroad's construction. According to the History Channel, a scandal involving the Crédit Mobilier company (formed by Union Pacific stockholders) saw investors (some of whom were members of Congress) bestowing contracts upon themselves and each other. This almost succeeded in bankrupting the Union Pacific Railroad in the early 1870s. The scandal led to the censure of two House members, ruined many other participants' careers, and tarnished their reputations. Corruption regarding the railroad continued regardless.

How the Transcontinental Railroad changed America

The world grew a little smaller, and the economy expanded after the railroad business took off, allowing companies to more easily ship their products coast-to-coast. Once the famous spike was driven into the Utah point where the two parts of the Transcontinental Railroad met, history had been made. Interstate trade was the main perk, according to PBS. Many positive developments came from the railroad's conception, including an increase in intellectual and cosmopolitan thinking, now that people in the East and West could more easily exchange ideas and learn from one another.

However, its cultural impact was problematic. Not only did it continue to wreak havoc on Native American communities, who had already been subjected to displacement and genocide, but it unleashed what some may argue was an "immoral" side of America. Mormon leaders, who were supportive of the railroad's economic and expansive promise, were worried that it would have a negative effect on their community. Utah's Brigham Young, who was the president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and one of the founders of Mormonism in Salt Lake City, purchased shares of stock in the Union Pacific Railroad with hopes to exert some sway in the railroad's political decisions.

The Transcontinental Railroad may have been the first of its scale, but it wouldn't be the last. Many lines expanded and branched outward from its path. By 1900, many routes ran parallel to the Pacific, welcoming settlers looking for land of their own.