The Most Disastrous Clinical Trials In History

Clinical trials can be thought of in different ways. Some of us think about life-saving vaccines and disease-busting drugs that make our lives better, healthier, and safer. Some of us think of that time in college for a quick cash infusion and volunteered for a trial or study. And some of us think about the hope that clinical trials can offer loved ones suffering from some terrible disease.

What all those perspectives have in common is positivity — the assumption that clinical trials are always well-designed, well-run, and created with our best interests in mind. And trials are an essential part of progress — a new treatment needs to be tested to confirm its efficacy, and our knowledge of disease and the body can't be improved without taking some risks. That's why the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has a lot of rules and guidelines dictating how trials should be designed and run.

But when things go wrong in a clinical trial, they can go spectacularly wrong. Since these trials typically involve experimenting with our bodies, the potential negative impact of a trial gone off the rails is enormous. Here are some of the most disastrous clinical trials in history.

The CAFÉ Trial

It seems like common sense that the participants in a clinical trial kind of set the tone — the more careful you are selecting your volunteers, and the more care you take with them during the trial, the better the results.

Which makes it incredible that the University of Minnesota Medical Center didn't take more care with the participants in a trial for the anti-psychotic drug Seroquel, all of whom were suffering from schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. In fact, as Mother Jones reports, the doctor in charge of the trial, Dr. Stephen Olson, actually used the threat of involuntary commitment to force a man named Dan Markingson to "volunteer" for the trial.

MDLinx reports that Markingson, who suffered from psychosis and homicidal tendencies, wasn't capable of consenting to participating in the study. And MinnPost details how Markingson's mother, Mary Weiss, desperately tried to get her son out of the trial — efforts that were blatantly ignored by everyone involved.

The results were tragic. Several participants attempted suicide — and two succeeded, including Markingson, who attempted to decapitate himself with a box cutter. The university managed to keep the mess under wraps for more than a decade — but a 2015 report issued by the Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor was so damaging that the university announced it was suspending its clinical trials of psychiatric drugs indefinitely.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The thalidomide debacle

As Helix Magazine reports, thalidomide was an exciting new product in the late 1950s. When it was introduced in Germany, it was the only non-barbiturate sedative available — and it was considered completely safe. Clinical trials had been conducted on animals without any notable side effects, and it was believed that it was nearly impossible to overdose on the stuff. Within a few years it was on sale in 46 countries and nearly as popular as aspirin. When a doctor discovered it helped with morning sickness, thalidomide began to be recommended to pregnant women.

In the United States, clinical trials with about 20,000 volunteers were begun — but the drug was never approved by the FDA because a lone inspector named Frances Kelsey raised the alarm — Thalidomide caused severe, horrific birth defects. As The New York Times reports, the company trying to bring thalidomide to the U.S., Richardson-Merrell, knew that the drug was being pulled from shelves in Germany as evidence of the birth defects mounted — but continued to push for approval anyway, even sending letters to doctors denying the problem.

As the National Library of Medicine notes, the problem was with the clinical trials used to test thalidomide's safety — no testing was done on pregnant animals at all, and the overall safety testing was concluded to have been "superficial." This failure resulted in the strengthening of laws regarding drug testing and the widening of the authority of regulatory bodies like the FDA.

The ROCKET trial

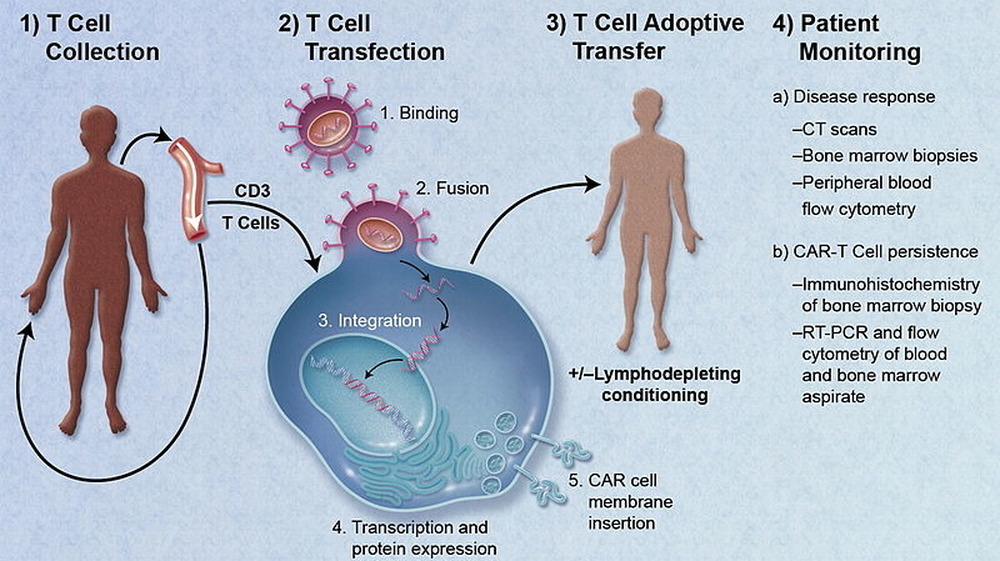

In the early 2000s, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy was expected to be the next big thing in cancer treatment. The technique alters immune cells in the body so they attack and destroy cancer cells and is still considered a promising line of research — no thanks to the disastrous ROCKET trial conducted by Juno Therapeutics in 2016.

As reported by Science, the trial was designed to test the CAR-T therapy on patients suffering from acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). But as Nature reports, within days of receiving the therapy, several patients developed cerebral edema — swelling of the brain — and five of them died.

The deaths threw the trial into chaos. Juno halted the trial immediately and conducted an extensive investigation into what went wrong. The safety risks involved with the treatment were well understood and could be dealt with easily, but this was something wholly new and unexpected. Forbes reports that Juno concluded that the problem lay in a specific "preconditioning" agent called fludarabine, administered to the patients to prepare them for the therapy — and that one patient given fludarabine had died from cerebral edema before the ROCKET trial began. Replacing the agent with an alternative appeared to solve the problem, and research into CAR-T therapy continues today.

The Johns Hopkins hexamethonium study

Medical research and drug testing involves a lot of risk, especially for the people who put their bodies on the front lines. But it's usually assumed that the medical experts conducting a trial — especially at a respected institution like Johns Hopkins University — are following all the rules and at the bare minimum not outright lying to their volunteers.

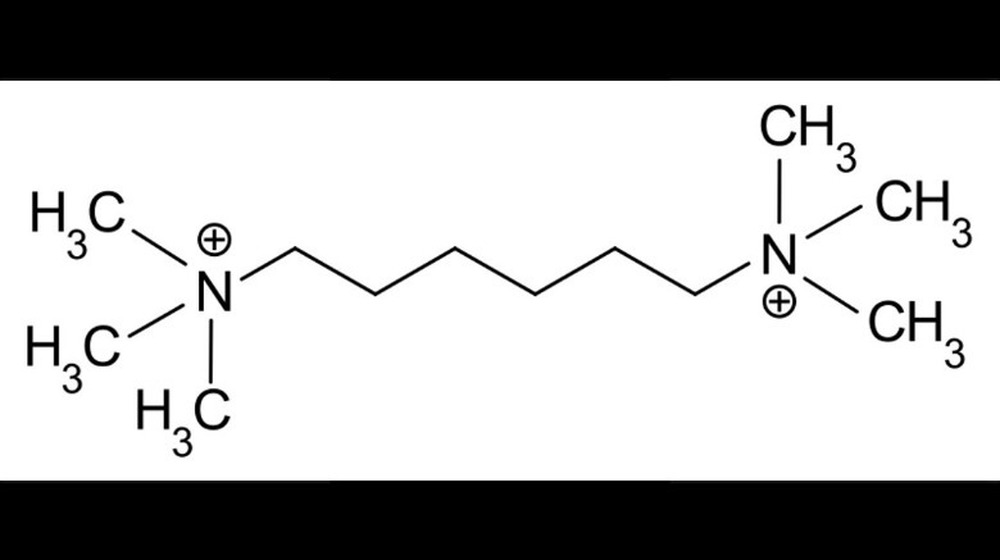

But as The New York Times reports, this wasn't the case when a young woman named Ellen Roche participated in a study on the causes of asthma. She signed a consent form, and two drugs were administered to her in order to simulate an asthma attack. One of the drugs, hexamethonium, had not been approved by the FDA and should never have been used in an experiment like this. Worse, Roche wasn't informed that hexamethonium wasn't approved — meaning her consent was meaningless.

According to the Journal of Medical Ethics, Roche quickly fell ill and experienced trouble breathing. She went to the hospital and was eventually put on a ventilator, but her lungs continued to deteriorate, and she died about a month after the experiment. The university suspended all of the trials being overseen by the principal investigator, Dr. Alkis Togias, as the FDA launched an investigation, and the family considered a lawsuit.

The "Elephant Man" trial

In March of 2006, six healthy men took part in a clinical trial for a drug called TGN1412 designed to treat the symptoms of leukemia and other disorders by manipulating their immune systems, as Lexology notes. TGN1412 had been through initial animal testing phases and had shown no problems. The trial was expected to be routine, though the dosing pace was increased alarmingly — the men received the drug ten times faster than in animal tests.

Just an hour into the trial, all six men began to experience some pretty horrific side effects. As reported by The Huffington Post, all six were rushed to intensive care as they experienced body swelling, organ failure, intense pain, vomiting, and fevers. The combination of symptoms was identified as a "cytokine storm," an extreme immune response. One of the men suffered terrible swelling in his head, gaining him the nickname "Elephant Man."

As New Scientist reports, an investigation concluded that the trial was faulty in many ways, including a failure to get a complete medical history of all the participants — but the adverse effects were the result of "unpredicted biological action of the drug in humans" and could not have been predicted.

All six men survived, though several had fingers and toes amputated, and it is speculated they may suffer long-term immune system damage.

The Ronald Maddison sarin gas study

When you agree to participate in a scientific study or a clinical trial, you usually assume the people running the program won't try to actively kill you. Sure, it's always possible they'll accidentally kill you, but it's usually safe to assume it won't be on purpose, at the very least.

But as The Guardian reports, that wasn't the case in 1953, when 20-year-old Ronald Maddison, an engineer with the Royal Air Force, volunteered to participate in some tests as part of a project to cure the common cold. Instead, the scientists running the program used Maddison to test the effects of sarin gas on human beings. Specifically, they wanted to know what the lethal dose of sarin was — so they put some on Maddison's skin.

Over the next 45 minutes, Maddison suffered horribly. He collapsed and began gasping for breath then went into convulsions. The ambulance driver who transported him described him turning blue, "like watching somebody pouring a blue liquid into a glass." BBC News reports that doctors administered several doses of antidote and then a shot of adrenaline to his heart — but Maddison died at the hospital despite their efforts. The government declared the experiment to be covered by the Government Secrets Act, and the facts surrounding Maddison's death were secret until a new inquest was ordered in 2004, nearly five decades later.

The Jesse Gelsinger gene therapy trial

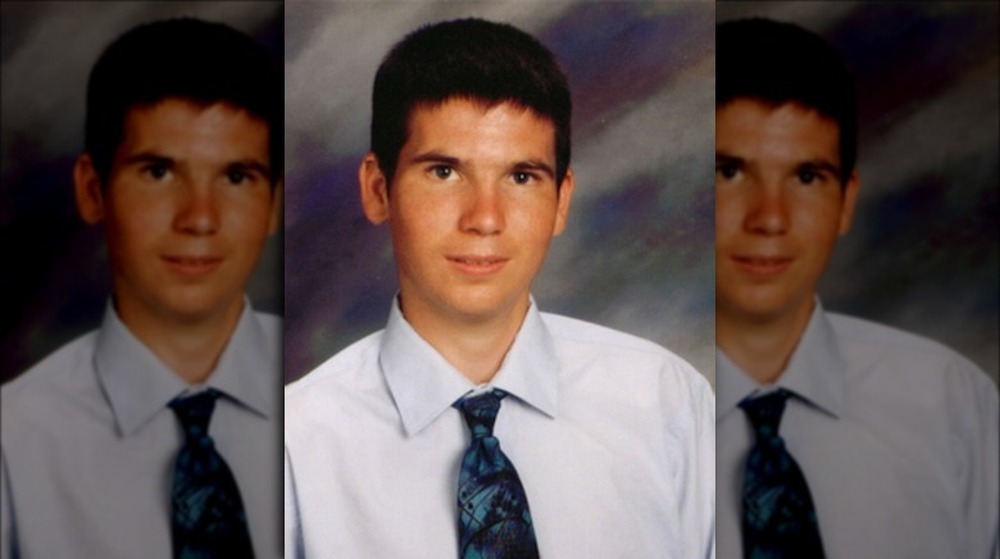

Jesse Gelsinger was born with ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency, a genetic defect affecting his liver that left him with dangerously high levels of ammonia. As The New York Times notes, he lived a relatively normal life, albeit one where his illness was controlled by an incredible strict diet and a large regimen of drugs — 32 pills a day. When Jesse was 18, he heard about a clinical trial for a new gene therapy that hoped to treat the condition in babies and very young children. Despite knowing the trial wouldn't help him directly, Gelsinger wanted to be part of the solution for future sufferers.

As The Science History Institute notes, the therapy had been tested on animals without problems and had even been tested on other human volunteers with only predictable side effects. There was every reason to believe that Gelsinger would have a similar experience. Instead, he experienced multi-organ failure and died.

The investigation into his death revealed many problems with the trial. For one, Gelsinger's liver function wasn't good enough — he should have been excluded from participating. They also failed to inform him about two monkeys that had died in earlier trails or about severe side effects some of the other human volunteers had experienced, which made his consent meaningless.

The Tuskegee trial

One of the most infamous experiments in modern history, the Tuskegee Trial began in 1932 with the aim of gathering data on syphilis. As History tells us, the project recruited 600 Black men from Macon County, Ala. — 399 of whom were infected with syphilis and a control group of 201 healthy men. The men were promised free healthcare in exchange for their participation, but what they got over the next 40 years was the exact opposite of that. As The Atlantic notes, the men were never told their diagnosis (most had no idea they had syphilis in the first place), and the men never received any treatment whatsoever — in fact, the project leaders sometimes worked to stop the subjects from receiving medical care.

This continued even after penicillin began to be used to treat syphilis in 1947 — the men in the Tsukegee Trial were only ever given aspirin and other placebos. The project's leaders wanted to see how the disease progressed — and they did. Many of the men recruited into the project went blind, went insane, or died as the disease ravaged their bodies.

By the time a reporter broke the story and had the project shut down in 1972, more than a hundred of the men had died from syphilis or complications of the disease. Even more horrifying, 40 of the men's wives were found to have been infected — and 19 of their children.

The BIA 10-2474 study

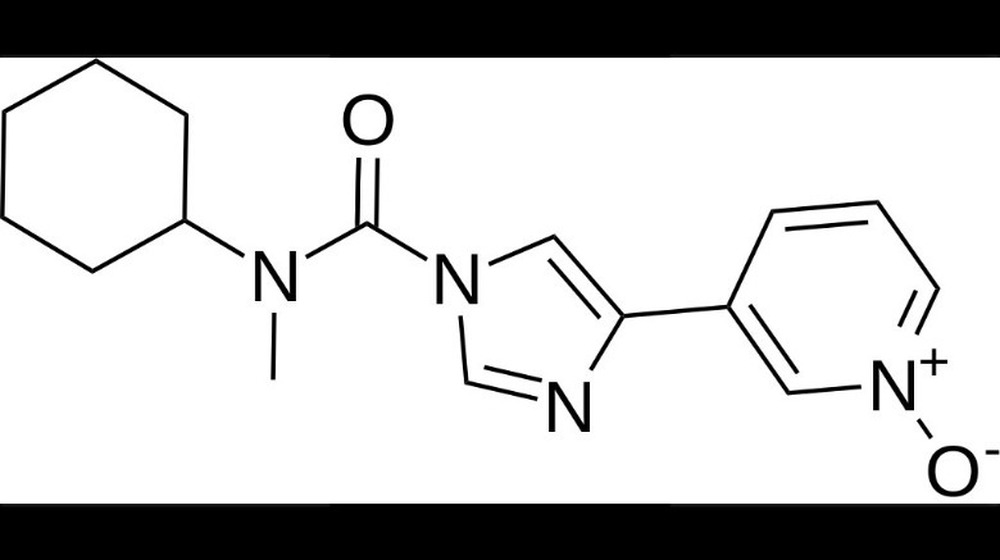

This French trial was launched in 2016 to test BIA 10-2474, a compound that affects the endocannabinoid system of the body. As Science reports, BIA 10-2474 was expected to be effective in reducing anxiety and in treating chronic pain and the symptoms of neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's Disease.

According to The Guardian, the trial recruited 108 people — 90 were given varying doses of the drug while the rest were given a placebo as a control group. Six of the volunteers, all men, received the highest dose of all — and all six became immediately ill. One was declared brain-dead shortly afterwards and died, and at least four others suffered brain damage — damage which may prove to be permanent.

Some scientists suspect that BIA 10-2474, which inhibits a specific enzyme, affects other enzymes unintentionally, causing "off-target" effects that resulted in the severe reactions. But as The Guardian reports, the earlier trial phases of the drug reportedly left several dogs dead and several others with brain damage — negative results which were ignored as the trial moved forward. François Peaucelle, director of Biotrial, the company that ran the trial, called the dogs' deaths "not significant."

The Trovan trial

The worst-case scenario for a clinical trial going wrong is when it involves children. Unfortunately, that's exactly what happened when a region of Nigeria was hit with a meningitis epidemic, and pharmaceutical company Pfizer distributed experimental drugs to sick children.

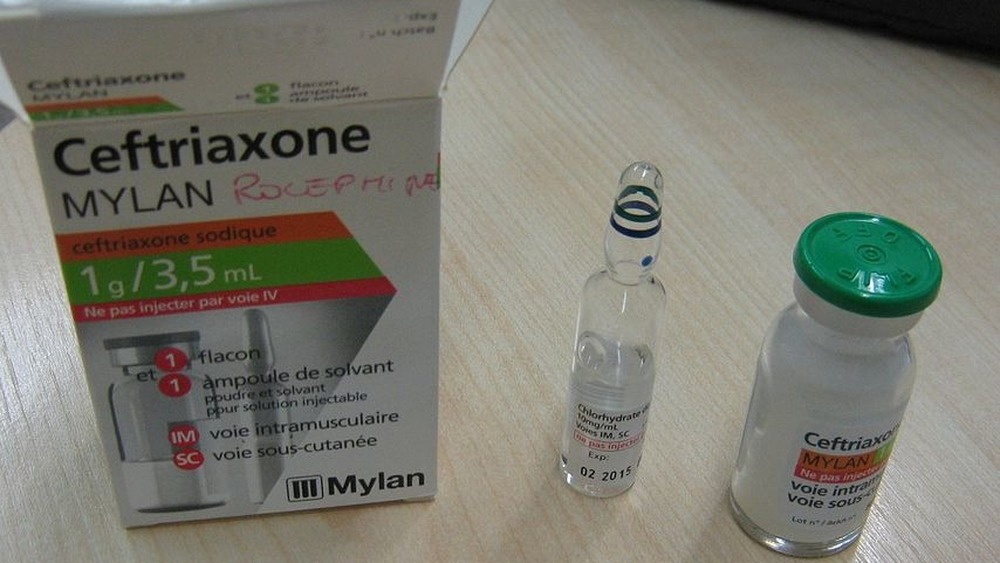

As The Guardian reports, Pfizer dosed one hundred children in the northern state of Kano in Nigeria with Trovan as part of a clinical trial testing its effectiveness against meningitis. One hundred other children were given ceftriaxone, the standard treatment. The results were not good but not clearly disastrous — of the 100 children who received Trovan, five died. But six children who received ceftriaxone died as well.

But when the parents of the dead children launched legal action against Pfizer, it was discovered that the company had not bothered to get permission to include all of the children in its trial. It was also alleged that some of the children who survived had been given incorrect dosages, resulting in brain damage and paralysis. Pfizer tried to argue that what had actually killed the children was the bacterial infection but eventually chose to settle the lawsuits to the tune of $75 million. Pfizer still intended to market Trovan but saw approval rescinded by the European Union due to concerns over its affect on the liver.

A so-called "trial" of a stem cell treatment

Macular degeneration is sadly common — according to WebMD, it's the leading cause of vision loss in people over the age of 60. Losing your vision is frightening, so it's no wonder that a group of elderly women living in Florida jumped at the chance to participate in a clinical trial testing a new stem cell treatment designed to cure the affliction.

Stem cells are "raw material" cells in the body that can be induced to become specialized cells, which can replace diseased or damaged cells. Which means in theory stem cells could someday cure a wide range of diseases and disorders. But as Gizmodo reports, instead of a cure, the women taking part in this trial lost their vision entirely about a week after the stem cells were injected directly into their eyes.

What's truly shocking about the incident is that this wasn't a real clinical trial — it was just a shady clinic seeking to make a quick buck. But the women who paid to participate in the "trial" were fooled because it was listed on the ClinicalTrials.gov site, making it look legit. But very little effort is made to police the listings on the site, making it easy for scammers to include their information, thus gaining instant credibility.

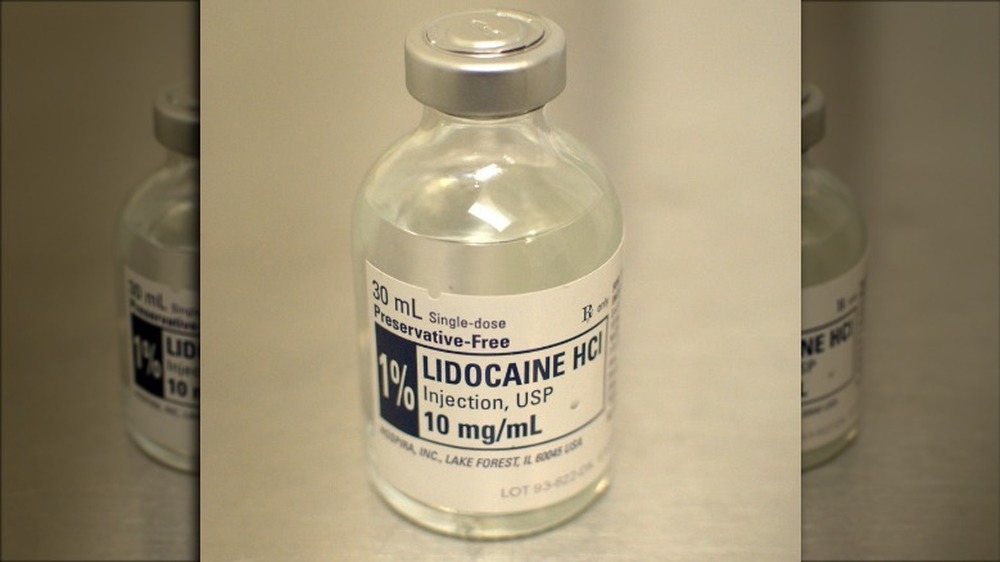

The Lidocaine lung study

Clinical trials are frequently used by broke people to make a little extra money. If you're lucky, you can make some easy bucks without suffering too many side effects.

As reported by The New York Times, that's what college student Nicole Wan hoped in 1996 when she agreed to be paid $150 to participate in a study seeking data on how the lungs fight pollution and infection. She would be given a local anesthetic, Lidocaine, and a bronchoscopy would be performed on her. This involved having a tube inserted down her throat into her lungs to collect cells.

Wan experienced discomfort during the procedure and kept coughing. So the researchers gave her more Lidocaine by spraying it directly into her throat — in fact, they exceeded the dosage limits they themselves had specified in their proposal. When the procedure was done, Wan felt weak and was in severe pain, but researchers sent her home. She died two days later when her heart stopped. An investigation revealed that the researchers had taken way too many cells from Wan's lungs, damaging them. And they'd given her way too much Lidocaine, poisoning her.

Wan was 19 at the time and signed on to the trial without her parents' knowledge, prompting questions surrounding her ability to consent. But in the end the only result was a modification of the guidelines used in trials.