Famous Artifacts Countries Want Back

All the big museums do it: They exhibit artifacts from other countries. But how many museums actually have a right to do so?

It's a difficult question to answer. In 2013, New York's Metropolitan Museum sent two statues back home after they were presented with evidence that they'd been stolen from a Cambodian temple. That's great, but according to The Verge, proving that something was definitely looted, stolen, or otherwise taken illegally is tough, even though the Archaeological Institute of America suggests that up to 90 percent of "classical and certain other types of artifacts" have ended up in museums under shady circumstances.

That's led to the establishment of a few organizations dedicated to proving that stolen artifacts were, indeed, stolen and trying to get them returned to their rightful countries. Sometimes, it works. In 2020, NPR reported that an 18th-century crown had been returned to Ethiopia 21 years after it went missing, and that's pretty cool.

But that's not always the case, and sometimes, nations holding these precious artifacts just sort of shrug and say, "Nah. It's pretty. We'll keep it." So, let's look at some of those cases where, really, countries just want what's rightfully theirs.

Greece wants their Elgin Marbles back

There's a huge part of the British Museum that's devoted to the frieze that once decorated the Parthenon in Athens, and Greece has — for a long time — been trying to get the pieces returned. Britain, however, keeps saying no.

According to National Geographic, the story is anything but straightforward. In 1803, Lord Elgin, also known as Thomas Bruce, Britain's one-time ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, arranged to remove a large portion of the Parthenon's frieze and other pieces of architectural elements. At the time, he had permission from Athens' Ottoman rulers, as well as from the Athens government itself. Just how much that "permission" was worth and how far Elgin bent the rules has been up for debate since, but there's more to the story.

By the time Elgin got there, the Parthenon had already been severely destroyed by war: An Italian admiral had tried to loot it (and destroyed entire statues in the process), part had been destroyed for building materials, and visitors had since adopted a "take a souvenir" attitude.

Elgin took the pieces to London at an insane expense, and they were installed in the British Museum in 1832 — the same year Greece got their independence and started trying to get the marbles back. They're still in London, and The Guardian says that after a renewed attempt by Greece in 2020, British prime minister Boris Johnson declared that they had been "rescued, quite rightly, by Elgin."

The DRC wants all their stuff back

In 2018, Marvel hit a home run with Black Panther, and it wasn't just superhero fun — it brought a longtime struggle of many African countries into sharp relief. The moment where Michael B. Jordan's Killmonger demands to know how a British museum got African artifacts is a scene that could play out across Europe — especially in Belgium.

In 2018, CNN reported that Belgium had reopened their Africa Museum. They'd spent years — and millions — renovating it, but there was still a massive problem: It was still home to scores of artifacts taken from Congo during one of the most brutal periods in the nation's history. According to The New York Times, the overwhelming majority of the 120,000+ items in the museum's collection were taken during the 80 years Belgium had Congo under the boot of colonialism, and it's dire stuff. Millions died as Belgian industrialists squeezed every bit of rubber they could out of the country, while touting their own superiority in the process. (They also "imported" Congolese people to exhibit in zoos, but that's a whole other story.)

Even though the Africa Museum's remodel is designed to be a little more honest with what happened, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is understandably unimpressed. The museum's reopening came alongside a statement from President Joseph Kabila that they were going to request the return of everything that had been stolen from them. The Africa Museum didn't answer.

Kenya wants their lions back

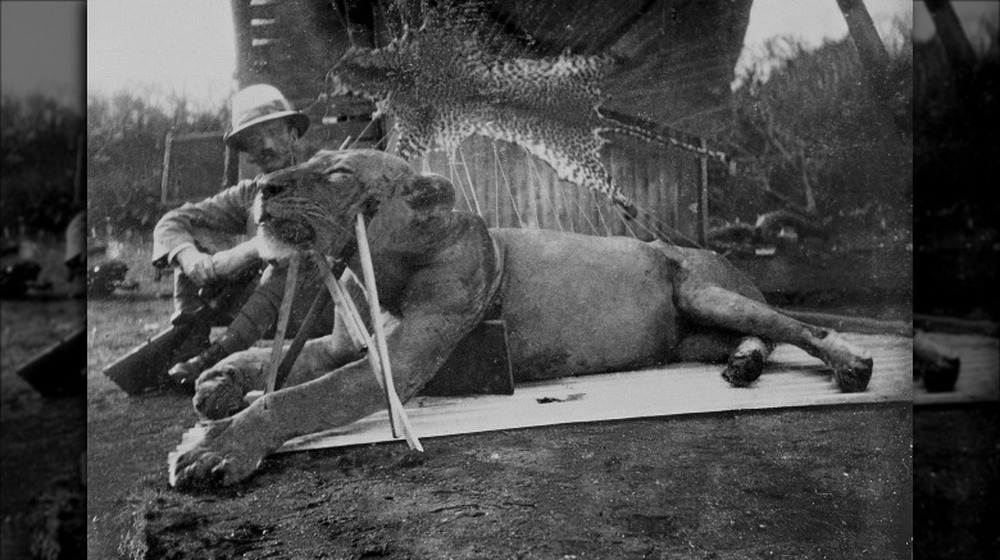

In 1996, Michael Douglas and Val Kilmer starred in The Ghost and the Darkness, a movie about two man-eating lions that stalked a crew trying to build a railroad in Africa. The movie was based on a true story, and "The Ghost" and "The Darkness" were the names given to the lions by the man who ultimately killed them, Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson (pictured with the first lion killed).

The lions were credited with (or blamed for) killing as many as 135 people in Kenya's Tsavo region in 1898. Recent chemical analysis confirmed that one lion was responsible for eating 10 people, while the other ate around 24, says Smithsonian Magazine. Isn't science neat? It's also known that the lions weren't natural man-eaters but opted for soft, squishy prey because of severe dental disease.

The remains of the lions were sold to the Chicago Field Museum, where they're still on display in spite of the fact that in 2007, the National Museum of Kenya issued a request to have the lions repatriated and ultimately included in the museum's sections on Kenyan history in a planned exhibition of their own (via the BBC).

Easter Island wants their monolith back

The world is full of mysteriously man-made creations, and for centuries, the moai of Easter Island and the Rapa Nui have captured the imaginations of everyone who sees them, and seeing them up close and personal is even more awe-inspiring.

Millions have had the chance to see one at the British Museum. The statue has been there since 1869, after Commodore Richard Powell of the HMS Topaz stopped at the island, dug up the four-ton statue, and sailed away with it. He gave it to Queen Victoria, who gave it to the museum, but the islanders of Rapa Nui want it back.

President of the Council of Elders Carlos Edmunds explained it like this (via The Guardian): "This is no rock. It embodies the spirit of an ancestor, almost like a grandfather. This is what we want returned to our island — not just a statue." The figure that stands in the British Museum isn't just any nameless ancestor, either — it's Hoa Hakananai'a, who was responsible for not only protecting the island's tribes but for encouraging them to work together.

While some cite the damage being done to Easter Island's in situ monuments (mostly from erosion) as a reason for the British Museum to keep theirs, Easter Island governor Tarita Alarcon Tapu issued this plea in 2019 (via The Guardian): "Give us a chance so he can come back. We are just a body. You, the British people, have our soul."

The Benin bronzes

The British Museum says that they have somewhere around 900 artifacts from the Kingdom of Benin, with around 100 on display at any given time. That includes the Benin Bronzes, which are a series of sculptures created for Benin City's royal court. Why are they in England? Between 1897 and 1960, Benin was under the umbrella of the British Empire, which happened in a way that Michigan State University Nigerian-American historian Nwando Achebe calls "very duplicitous," (via the Australian Broadcasting Corporation) and clarifies that at the time, what was talked about and what was included in the signed treaties were two entirely different things. So, many didn't know that they were essentially turning over the keys to the kingdom ... and much more.

What followed could fill books, but the bottom line is that when Benin's king pushed back, the Brits pushed harder. They killed thousands, destroyed huge areas of the city, and plundered all the treasure they could carry — including the bronzes now in the British Museum's collection.

Things seemed to be moving in 2018, when CNN announced that the bronzes were going back to Nigeria ... but they weren't being returned. They were being loaned. And that's called adding insult to injury. By 2020, permanent museums had been built to host the bronzes, but the BBC stressed that they were simply being lent in a program highly dependent on one man: Governor Godwin Obaseki, who negotiated the deal. Should he leave office, well, what happens to the deal is anyone's guess.

Egypt wants the Rosetta Stone back

"Rosetta Stone" might be more familiar as the name of some expensive language-learning software, so it's easy to overlook how valuable the original is. Carved into the stone are three different languages (Demotic, ancient Greek, and Egyptian hieroglyphs), which acted as a code-breaker that allowed for the translation of the hieroglyphs. It might seem logical that it's in Egypt, but it's not — it's been at the British Museum for more than two centuries.

It was originally discovered by the French, specifically, says History, by a soldier under Napoleon's command. It was July 19, 1799, when it was found, and under Napoleon's order to seize all culturally important artifacts, the Rosetta Stone was swept up, up, and away ... briefly. When Napoleon's rule came to an end at the hands of the British, they decided that they were going to take some goodies as spoils of war, including, of course, the stone.

The Egypt Independent says that by 1802, it was in the British Museum, where it stayed without incident until 2003. That's the first time Egypt asked for their artifact back, and since then, requests have been issued fairly regularly. Just as regularly, Britain has continued to say, "Nope."

Egypt also wants the bust of Nefertiti back

The thing about ambassadors is that when someone from one country sets up shop in another country to act as a go-between, it's usually a mutual sort of thing. That's what makes Professor Hermann Parzinger's response to Egypt's plea to return the 3,400-year-old bust of Nefertiti so weird.

Parzinger is the president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, which oversees the Berlin museum where the bust is kept. When he got the formal request from Egypt, he responded (via Reuters): "The foundation's position on the return of Nefertiti remains unchanged. She is and remains the ambassador of Egypt in Berlin."

That's not really how ambassadors work, but okay? Egypt has every right to be angry, as the bust was taken to Germany not long after its discovery in 1912, when documents seem to indicate the finders helped get the rights to keep it by playing it off as no big deal, instead of the whopping big deal it actually was. Al-Monitor says Egypt claims it was smuggled out of the country and Germany never had any permission to take it whatsoever, but that hasn't prevented them from both refusing to return it and being stingy with the research.

Smithsonian Magazine says that when the Neues Museum did a 3D scan of the bust, they even refused to share that — with anyone. It was years before the scans were released, and when they were, they included a copyright notice saying the museum had all rights to the image.

India wants the Koh-i-Noor diamond back

When it comes to flaunting something stolen, there's no artifact that's quite as high-profile as the Koh-i-Noor diamond. Even those who aren't familiar with it by that name have probably seen it — it's the biggest piece of bling in England's Crown Jewels. It's also cursed, if anyone believes that sort of thing, but let's talk about the part where India has been trying to get their massive stone back for years.

No one's really sure where history and myth overlap when it comes to stories about the diamond, but according to Koh-i-Noor researchers Anita Anand and William Dalrymple (via Smithsonian Magazine), the first time it appeared was in 1628, when it was a centerpiece of a massive, gem-encrusted throne. By the time it ended up with the Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh, it wasn't just pretty. It was a symbol of power.

And that's why the British included in it a deal that not only took the diamond but took all independence from India, too. It eventually got included in the Crown Jewels, and it's regularly been the subject of an exchange where India says they want it back, and Britain says no. According to India (via the BBC), returning the stone would be giving it back to a rightful owner, while David Cameron's 2013 statement kind of summed up Britain's whole position on it: He said it wasn't a "sensible" thing to do.

China wants their bronze zodiac back

The story starts with a little-known chapter in Chinese history: the 1860 destruction of the Old Summer Palace by British forces, who turned one of China's most revered sites into ruins in retribution for the killing of Times reporter Thomas Bowlby. It's more complicated than that, of course, but the end result was that the palace was destroyed — oddly, by Lord Elgin of Elgin Marbles fame. Before that happened, though, the BBC says that the site had already been looted in a joint effort between the French and the British. Treasures had been seized and auctioned, in part to raise money to pay the military.

Among the stolen treasures was a set of bronze animal heads, representing the animals of the Chinese zodiac. Some have been found and returned: The BBC reported that in December 2020, the horse (pictured) had been donated back to China by casino tycoon Stanley Ho after his death. In 2013, Reuters reported that the rat and the rabbit were purchased and returned by Kering exec Francois-Henri Pinault.

The horse was the seventh head to be returned, and that's encouraged a call for the five missing heads. According to the Global Times, the sheep, snake, rooster, dragon, and dog are still missing, and while photos of what may have been the dragon and the dog have surfaced, it's uncertain whether they were, in fact, the missing heads or what has become of them since.

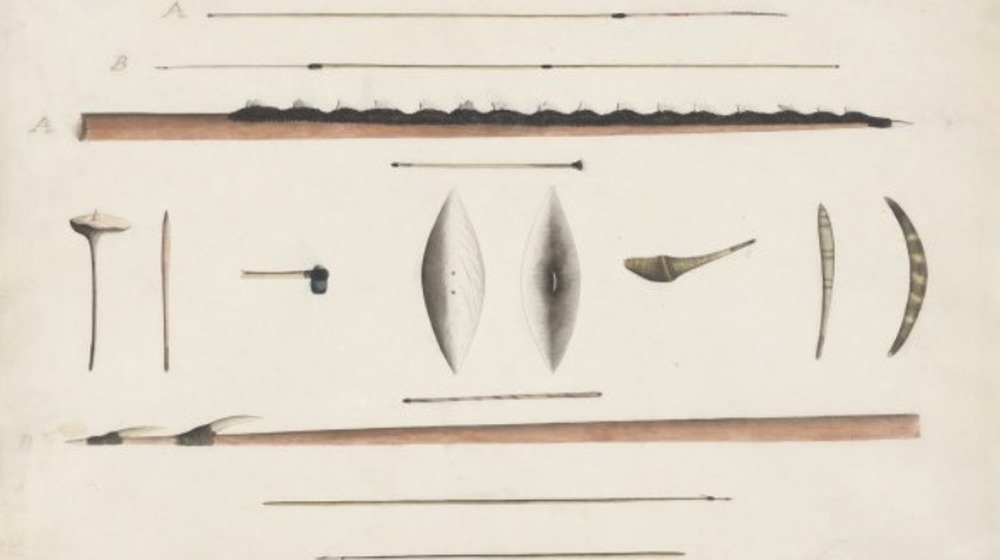

Australia wants the Gweagal shield back

Captain James Cook was the first to "discover" Botany Bay in 1770 ... except for, well, all the people who had been living there for a good long time. During those first encounters with the Aboriginal people, a Gweagal man named Cooman was shot and killed. Cook and his men took his shield and his weapons, added them to the treasure trove of loot they had on board the HMS Endeavor, and headed back to England.

According to The Guardian, it isn't just Australia's Aboriginal people who are trying to get the British to return the shield that's now in the British Museum. It's also Cooman's descendent, Rodney Kelly. In 2019, Kelly went to the British Museum, where he was allowed to pick up the shield that his ancestor died holding. He said (via the Australian Broadcasting Corporation): "... that proud moment and happy moment just turned to sadness and sorrow because I knew the shield was going back into its case."

While the British Museum has said they're open to loaning the shield to an installation in Australia, Kelly has said that's just not good enough: "The significance to our culture far outweighs any visitors who come here and just stroll past the shield without really knowing the history of it."

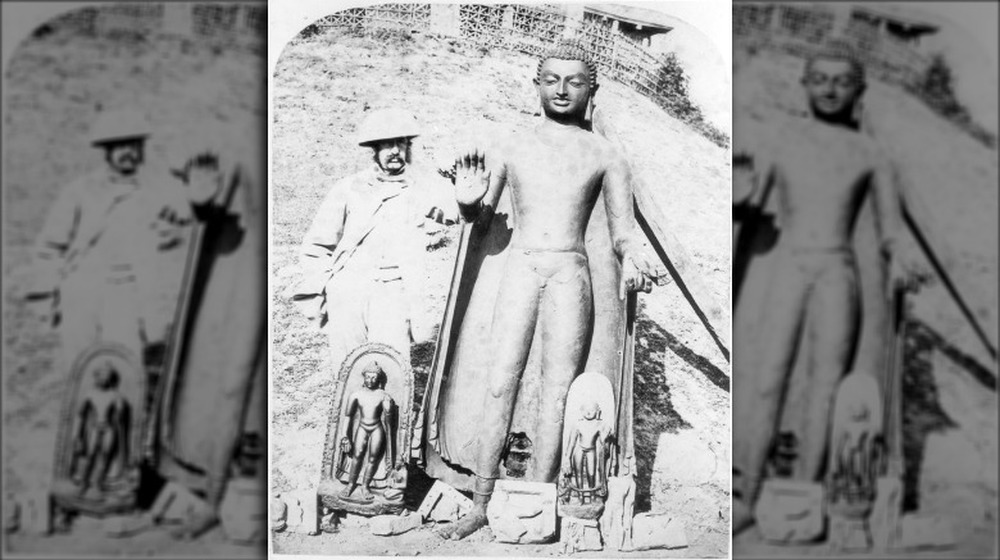

India wants the Sultanganj Buddha back

Listen to the BBC, and the Sultanganj Buddha plays an integral part in the lives of those belonging to Birmingham's Buddhist community. Listen to The Telegraph India, and they want their statue back.

The copper statue dates to sometime in the seventh century, and it's an impressive piece: Standing over six and a half feet tall and weighing around 1,000 pounds, it's the largest — and only — of its kind. That alone is enough to make it culturally significant, and how it ended up in an English city is more than a little shady.

The Sultanganj Buddha was discovered in the 1860s during a railway construction project, and when workers uncovered it in the ruins of a Buddhist monastery, word got back to Birmingham's then-mayor. He definitely wanted it for the city's museum, so he paid to have it shipped back and then donated it. It became the centerpiece of a Buddhist art gallery ... although lore says the statue almost didn't make it and was nearly snagged by the British Museum. India, meanwhile, believes it should be in Sultanganj, a pilgrimage site for the faithful.

A village wants the Monteleone chariot back

This particular tale starts when a property owner discovered an ancient, subterranean burial chamber on his land and took it upon himself to excavate the goods inside. (This was 1902, and things were different then.) The pre-Roman chariot ended up being purchased for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it's been ever since.

Here's where things get complicated. NPR says that story — the one told on the Met's history of the item — isn't the whole thing. They add that it was actually found by a shepherd who — in desperate need of a new roof and not knowing what he had — sold it for the value of the scrap metal. Someone did know what it was: J.P. Morgan, who was the ultimate buyer. He bought it and took it to the US before the Italian parliament could complete their inquiry into the provenance of the chariot, which is basically the international equivalent of raiding the grocery store and snagging the Oreos before anyone else in the house knows they're there.

Italy's official stance is, "Oops, finders, keepers, we guess," but Monteleone di Spoleto, the village of 600 that was the chariot's original resting place, wants their artifact back. Mayor Nando Durastanti puts it this way: "The chariot is in the DNA of the people [...] It is connected to the men and women who lived here in the past and who live here today."