What It Was Like Living In Berlin During The Cold War

"Berlin is the testicles of the West. When I want the West to scream, I squeeze on Berlin."

Thus spoke Nikita Khrushchev, first secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, at a gathering in Yugoslavia in 1963, according to Alpha History. Khrushchev's metaphor, coarse as it may be, provides a vivid and memorable starting point for thinking about the German capital, which, after being ravaged by aerial bombardments and brutal street battles in the final months of World War II, was destined to serve as the nexus of yet another conflict that would continue to dominate the lives of Berliners for a large part of the 20th century.

The Cold War escalated between the allied powers of Western Europe and the Soviet Union — a former ally against Nazi Germany — after 1945, a power struggle centered around the balance of powers in the conquered country of Germany and its surrounding territories, with Berlin as its "hotspot," according to Berlin.de.

Most people know something about the Cold War from history books, but amid the maneuvering of postwar superpowers, it's easy to forget the impact that the conflict had on the lives of those who had already lived through so much horror. Here is the story of normal, everyday Berliners who lived through the Cold War.

Postwar Berlin and the Soviet Blockade

Berlin was the city where World War II ended, with the Western Allies of Britain, France, and the United States having essentially met the forces of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in the streets of the city where they eliminated the opposition forces. As a result, Berlin was carved up, with each of the four powers laying claim to their own "sector," according to the Imperial War Museum. The city itself lay 200 miles inside Communist-controlled East Germany, and it wasn't long before former alliances were tested due to "growing conflicts of interest," as described by Berlin.de.

Within the Soviet sector, a forced merger of two political parties, the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD), occurred in 1946. They became the Communist-controlled Socialist Unity Party (SED), which essentially came to hold a political monopoly in East Berlin, laying the groundwork for the German Democratic Republic (GDR) — the official name of Soviet-controlled East Berlin — and becoming akin to a totalitarian state.

By 1948, and with tensions in Berlin increasing, the Soviets were incensed by the movement between the Western Allies toward unifying their sectors as a "single economic unit" with a shared currency, "which the Soviets regarded as a violation of agreements with the Allies," per Britannica. Thus, the Soviets ended the four-way power-sharing agreement and instead instituted a blockade in an attempt to force the Allies to abandon their sectors.

Berliners were dependent on the Berlin Airlift

The Berlin Blockade instigated by the Soviet Union began in June 1948 and saw them block "all rail, road and canal access to the western zones of Berlin. Suddenly, some 2.5 million civilians had no access to food, medicine, fuel, electricity and other basic goods," according to History.

Citizens who had lived though the war and had seen their city turn to rubble around them found once again that they were at the epicenter of global political turmoil. The move by the Soviets was intended to force the Allies to relinquish control of Berlin exclusively to the East, at the risk of seeing its people starve. Instead, the Allies undertook what History describes as "the first major conflict of the Cold War," the Berlin Airlift, during which more than two million tons of supplies were dropped into West Berlin by cargo plane before being carefully rationed.

A great humanitarian effort, the Berlin Airlift was a major PR coup for the Allies in the early years of this new conflict. In addition to providing necessities, pilots such as Colonel Gail "Hal" Halverson won the hearts of West Berliners with "Operation Little Vittles," in which he dropped parcels of candy to the city's children attached to little parachutes. Per Britannica, "As a result of the blockade and airlift, Berlin became a symbol of the Allies' willingness to oppose further Soviet expansion in Europe."

East German refugees streamed into the West

The Berlin Blockade ended in the spring of 1949, when it became clear to the Soviets that it hadn't convinced the people of West Berlin to forsake the Allies or stopped them from becoming a unified state, per History.

Meanwhile, as the years rolled on, conditions grew worse for the people of East Germany. Though officially known as the German Democratic Republic, "It was neither democratic, nor was it a republic. It was a dictatorship in which there were no free elections, no division of powers, and no freedom of movement," according to Berlin's Museum in the Kulturbrauerei.

As a result, West Berlin became the destination for disaffected East Germans looking to escape the totalitarian grip of the GDR. According to the John F. Kennedy Library: "By 1961, four million East Germans had moved west. This exodus illustrated East Germans' dissatisfaction with their way of life, and posed an economic threat as well, since East Germany was losing its workers."

The Berlin Wall splits the city into two

Knowing that such a colossal brain drain posed an existential threat to the GDR, the SED, backed by the USSR, hatched a plan to keep its citizens from fleeing to West Berlin. The policy became one of the most notorious and condemned in postwar European history, leaving a scar on the city of Berlin that would only come to be healed in the final years of the 20th century.

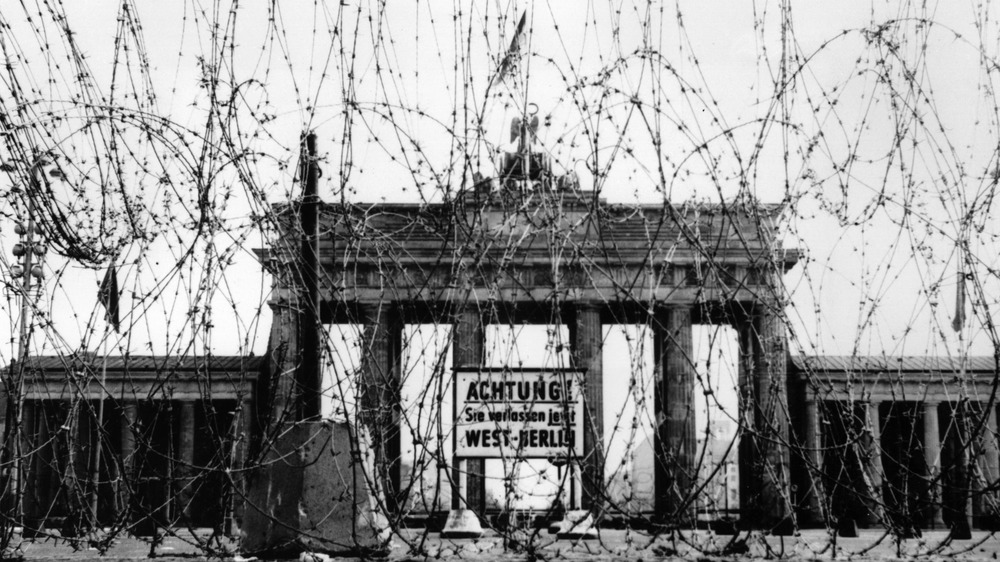

In the middle of the night on August 13, 1961 — when "a sixth of the East German population had already moved West," according to the Forces Network – the SED sanctioned the construction of barriers between East and West, while East German police began to halt traffic and border crossings. "Over the next few days and weeks, the coils of barbed wire strung along the border to West Berlin were replaced by a wall of concrete slabs and hollow blocks," per Berlin.de, which notes that, over the coming months, 111.9 kilometers of "fortifications" were built to prevent East Germans from freely entering West Berlin, with citizens instantly separated from their friends and family on the other side of the wall.

As an indicator of how truly divided the city had now become, Visit Berlin notes that "it took ten years after the Berlin Wall was put up, before a total of ten direct telephone lines connected East and West Berlin." The Berlin Wall was to divide the city for a total of 28 years.

Kennedy visits the people of West Berlin

Condemnation from the furious Allies was swift. Though built out of a sense of totalitarian pragmatism which dictated that East Germans must remain citizens of the GDR, the creation of the Berlin Wall by the SED seemed premeditated to raise the stakes in the escalating Cold War — at the expense of the German people. According to Berlin.de, the mayor of West Berlin, Willy Brandt, declared: "The Berlin Senate publicly condemns the illegal and inhuman measures being taken by those who are dividing Germany, oppressing East Berlin, and threatening West Berlin."

When US president John F. Kennedy attended a summit in Vienna with his Soviet counterpart, Nikita Khrushchev, in 1961, he was apparently "unsettled" by the threat that access to West Berlin may be cut off by the Soviets, according to the JFK Library, and alerted the US military to prepare for possible military intervention. Though the Cold War is often characterized today as a bitter political stalemate, for Berliners at the time, the threat of living in a battleground once again was a very real possibility.

In 1963, Kennedy became the first American president to visit Berlin since the end of WWII, and he was met by "ecstatic" crowds. Kennedy's famous "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech came to symbolize the West's struggle to liberate the city from the divisive tactics of the USSR.

The Stasi – East Germany's secret police

Despite the leverage of such a superpower as the USSR, East Germany was a highly paranoid state, grappling constantly with the specter of the West and the potential disloyalty of its citizens. The Ministerium für Staatsicherheit (Ministry for State Security), or Stasi for short, was the GDR's secret police force, established to keep the citizens of West Germany in check and to ensure the integrity of the prevailing political hegemony. According to Britannica, the Stasi soon became "one of the most hated and feared institutions of the East German communist government."

Per Britannica, the Stasi's "formal role was not defined in the legislation, [but] was responsible for both domestic political surveillance and foreign espionage." As such, the Stasi bugged suspected subversives' homes and telephones and compiled reports on those they deemed disloyal to the state, gathering bodies of evidence to justify arrest and imprisonment. According to The Guardian, the GDR "built one of the most tightly controlled surveillance regimes in history. The Stasi created a vast web of full-time agents and part-time spies, with some historians calculating that there was one informant for every 6.5 citizens."

But the Stasi also became known as an organ of retaliation, according to Britannica, which claims the institution kidnapped and brought back East German officials who'd managed to escape the country. Often, these unfortunate souls were executed.

East Berliners endured constant supply shortages

But even declaring loyalty to the GDR would fail to bring about the way of life that was being enjoyed by East Berliners' neighbors in the West.

The Forces Network spoke to Heidi Brauer, who grew up in East Berlin during the Cold War, in the shadow of the Berlin Wall that, for decades, separated her from her father in the West. "If you wanted to buy a car that was a small Trabby Trabant you had to wait for 10 to 12 years," Brauer remembers. "We could buy in the wintertime maybe 1kg bananas or oranges but that was it. And with clothes that was the same. You had to organise to look around."

And though the SED coordinated and conspired to present to the world the image of the GDR as a legitimate and functioning state, reports emerged of the dire straits in which the people of East Germany found themselves. "East Germany is facing a new year of persistent food shortages and price rises for basic consumer goods, according to knowledgeable sources in East Berlin," read an article published in The New York Times two days before Christmas 1970, which goes on to describe the country's severe lack in particular of butter, meat, and coffee and weighs the chances of civil unrest.

The Berlin Wall was heavily guarded – and deadly

The word "wall" perhaps gives a false impression of what was dividing East Germans from their loved ones in West Berlin. The original fences that went up on August 13, 1961, were indeed replaced with concrete walls, but accompanying this were a range of military measures to deter — or otherwise kill — would-be escapees attempting to flee to the West. "More than 7,000 East German soldiers manned 302 watchtowers and 20 bunkers. At night, with lamp posts every 30 metres, it was the best-lit part of Berlin," says The Local, adding: "There were also alarms, ditches, barbed wire, guard dogs and devices that automatically fired shots" at those attempting to cross.

The eastern side of the wall was also protected by an extended area of no-man's land, known colloquially as the "Death Strip," while GDR guards also patrolled Berlin's River Spree. Those living nearby were therefore living hand in hand with a constant, lethal military presence and would think twice before attempting to cross.

Daring escapes into West Berlin

Despite the many dangers with which the Berlin Wall was defended, a great number of gutsy East Berliners were willing to try their luck at escaping into the West — and some devised some ingenious ways of making their way to freedom.

CNET reports the famous story of the families of Günter Wetzel and Peter Strelzyk, who, after stockpiling nearly 14,000 square feet of taffeta, a fine women fabric, constructed a makeshift hot-air balloon to carry them to freedom in West Berlin one night in 1979.

Perhaps the most audacious of escapes from East Berlin is that of the three Bethke brothers, who, over the course of 14 years, worked together to make it to the West one by one. The first, Ingo, cut his way through a border fence in 1975, according to History, while his brother Holger, with Ingo's help, glided to freedom by zip wire in 1983. The two reunited brothers then schemed to rescue their youngest sibling, Egbert, whom they eventually liberated from the East in 1989 via a pair of lightweight aircraft, flying over the wall, picking him up, and bringing him back to the West.

In total, an estimated 5,075 people managed to escape while the Berlin Wall was up, according to The Local, out of more than 100,000 attempts. Around 140 people lost their lives.

The fall of the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall finally fell – metaphorically at least — on November 9, 1989. It was a sudden and unexpected change in fortunes for a city that had continued to bear the brunt of the political fallout in the years following World War II, and the date serves today as one of the most jubilant and celebrated moments of 20th-century European history.

Thanks to looser restrictions coming into place at border crossings all along the Iron Curtain, the SED had come under pressure to allow greater freedom of movement for the people of Berlin. Senior GDR official Günter Schabowski was giving what was expected to be a regular press conference on the day the Wall fell, but things quickly unraveled when he announced that, "Permanent relocation can be done through all border checkpoints between the GDR into the FRG or West Berlin" and that such changes were effective immediately, according to Time. The botched announcement saw thousands of East Berliners descending upon the city's checkpoints, demanding to be let through. When the confused guards finally acquiesced, the streets were filled with tearful scenes of families and friends being reunited, of Berliners crossing and re-crossing the Wall freely for the first time since 1961.

The hours following the first crossing have been described as "a street party with sledgehammers," as Berliners took to destroying the symbol of their three-decade-long oppression piece by piece.

A party city is born

More than two million East Berliners celebrated in West Berlin in the hours and days following the opening of the Berlin checkpoints, according to History, with a journalist describing it as the "greatest street party in the world."

The subversive nature of Berlin and its people, which can still be seen and felt today, was in many ways born in the months and years of the city's demilitarization, as the fortifications and military outposts stationed along the abandoned Berlin Wall began to be reclaimed by the citizens they once divided. Mitte, the central neighborhood of Berlin, became a hot spot for musicians, artists, and creatives from both sides of the wall to express their newfound freedom through the establishment of squats and communes in the abandoned buildings of the GDR. "People hoped that the collapse of the regime would not simply result in a takeover by the West. People wanted to create something better, because neither system was perfect," Digital Hardcore Recordings founder Alec Empire told Electronic Beats.

The groundwork had been lain not only for the vibrant alternative club and art scene for which the city is now famous but also for Berlin's reputation for political activism and unorthodoxy, which has remained ever since. "It was not only the physical Wall that fell on November 9. It was also the many invisible walls that closed off anyone who didn't conform," says Slow Travel Berlin.

The Iron Curtain opens and Berlin officially reunites

With free access to West Germany, citizens of the GDR — 2.5 million of whom are believed to have crossed the border in the weeks following the fall of the wall – became newly aware of the austere conditions they had been forced to exist under for so long. Per History Extra: "Once the initial excitement had subsided, East Germans faced a serious decision about their future."

US president George H.W. Bush met with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in Malta on December 2, 1989. Though historians are split on the real-world impact of the Malta Summit, according to the Wilson Center, it allowed for "the emergence of a clearer sense of how the rival Soviet and American positions would interact, most directly, over the possibility of German reunification."

With the Iron Curtain opening across Europe and the Cold War deescalating, the people of East Germany were given the chance to decide of their own future. "In the first free elections in the GDR for 40 years, they voted in favor of a speedy reunification with West Germany, which promised huge benefits: free elections, freedom of speech, freedom of travel," according to History Extra.

Berlin is now the capital of a thriving united Germany, a central partner in the European Union, but traces of its fractured past are visible everywhere still, noticeable in the differences between East Berlin and West Berlin accents, architecture, and even the traffic lights.