The True Story Of The Potato Famine

Famines have devastated countries with limited access to resources or in the aftermath of a natural disaster for centuries. However, few famines have wreaked havoc to a nation like the Irish Potato Famine in the middle of the 19th century. In a span of less than a decade, the population of Ireland decreased drastically, with the citizens either succumbing to starvation or disease as a result of diseased crops. For many desperate Irish citizens, the famine forced them to flee to different parts of the globe, hoping to find some salvation that was not present in their homeland.

Tragically, the devastation that Ireland went through could have all been avoided. The country did not suffer from an earthquake or volcanic eruption that made the land uninhabitable, and resources were available both in their colonial mother nation and from around the world. As stated in PubMed, famines in the modern day are typically man-made. This comes from the failure to distribute an already existing supply of food because of either political interference or wealth inequality that results in those suffering not having the money to pay for the necessary food.

Both issues existed that made the Irish Potato Famine as devastating as it was. The famine did not have to completely change the demographics of the nation. However, the true story of the Irish Potato Famine will illustrate how bureaucratic failures led to a permanent scar on the world.

Origins of the Irish Potato Famine

According to History, the Irish Potato Famine lasted from 1845-1852. While the famine lasted only seven years, over 1 million Irish men, women, and children died from starvation, diseases, and a variety of other issues that arose during the period, and another million fled the nation. The origins of the famine however can be found all the way back to the beginning of the 19th century.

In 1801, the ratification of the Acts of Union made Ireland a colony of Great Britain. Like many colonial states, Ireland was limited in its own governance, as well as society as a whole. Protestant England made it illegal for Catholics in Ireland to own land or lease land, vote, or hold any government position, leaving the vast majority of the populous powerless to the more favored, well-to-do Protestant Irish class. In 1829, many of the laws were repealed, though the society was already established, and most Irish citizens were forced to work and live on landowner's property.

Even farther back than that, anti-Irish sentiment existed in Great Britain. According to History, the Irish were stereotyped as sub-human in order to differentiate them from Anglo-Saxons. The Irish were also attacked for being Catholic. It became common once the Irish began to emigrate during the famine to be barred from employment and even attacked in the street. With the class and ethnic divisions set, as stated in Live Science, a South American pathogen made its way to an unprepared Ireland.

The potato importance in Ireland

As the class divisions in Ireland worsened, along with their subjugation by Britain and wealthy Irish landlords, the Irish working class found salvation in the potato. While that may sound silly, the potato held up the Irish population.

The potato itself was not Irish in origin, however. Wesley Johnston states that the potato is native to South America. In the 1500s, Spanish conquistadors discovered the crop during their invasions and shipped it back to Europe. It was not until the 1590s that the potato first appeared in Ireland, and it was not until the 1750s that the potato acclimated to the Irish climate for mass consumption.

According to Britannica, the potato was consumed throughout Ireland, especially by the working class. This was because of its nutritional value and the ease and cheapness that the crop could be grown. However, because the potato was so prevalent as a crop in the Irish lower and middle class, any failure of the crop meant famine. Like a high wire act, any mistake would have tragic results.

Over the next 50 years, as new potato crops developed in Ireland, the imported crop became a staple of the Irish diet and economy. The countryside boomed as excess potatoes could be sold to underdeveloped parts of the nation, and by the 1830s, 30% to 35% of Irish citizens depended on the potato as their main source of food. Farmers in the province of Connaught would eat up to three potatoes daily!

The first cases of blight

September 1845 in Ireland marked the beginning of a dark episode in the country's history. As told by History Place, the leaves on potato plants turned black and curled before soon rotting. An airborne fungus originally from North America had traveled to England, and winds from southern England had carried the fungus to Ireland. Blight had come to the country. They were the perfect conditions, as the cool breeze and the moist conditions of the Irish farmland meant that a single blight spore that landed on a potato leaf could infect fields of potatoes within days.

Irish citizens formed their own theories for the deadly pathogen. Some blamed static electricity in the air from locomotives, while others believed it was "mortiferous vapors" from volcanic eruptions from within the earth. A religious people, some viewed it as divine punishment.

That October, news reached London of the crop failure in Ireland. Initially, many in England viewed it as an act from God. It was seen as a blessing so that the citizens would stop being dependent on the potato and break the cycle of poverty. England did not take the early days of famine with much importance, as 16 famines had occurred in Ireland since 1800. However, the famines in those years were local emergencies. England did set up a Relief Commission in Dublin for job and food distribution projects in the country, though this had limited success because of an uneducated lower class and uninterested landowning class.

Initial response to the famine

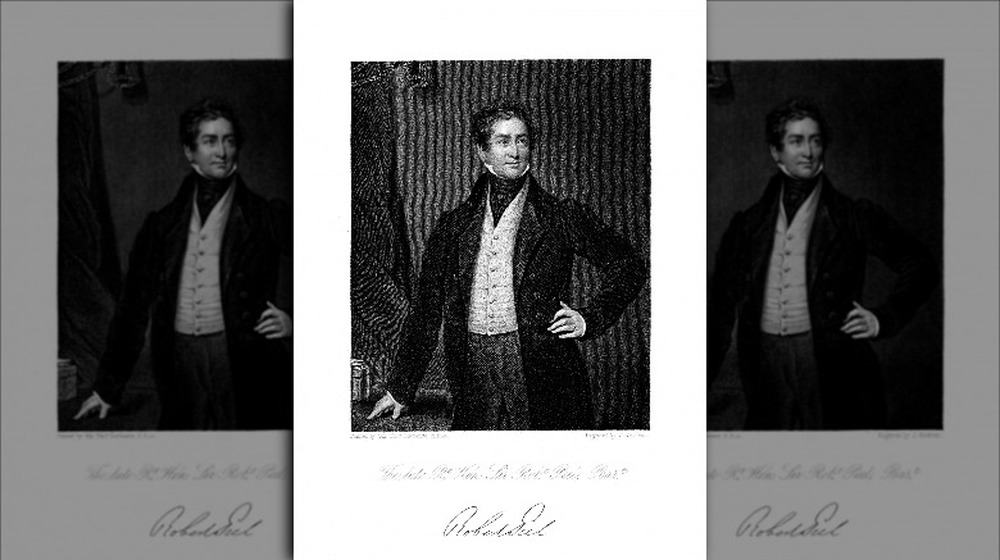

As Ireland struggled with their failing potato crop and the oncoming winter season, England, like a proper and caring mother nation, did what they could to help their subjects.... plunge deeper into despair and death. According to The Gazette, the initial reports out of Ireland were met by uncaring British Parliament and Prime Minister Robert Peel. They either did not believe the reports or thought the details were being exaggerated. By the time the nation understood the severity of the problem, their actions still failed to meet the moment.

Peel, once he understood the severity of the problem, did lower the price of bread and repealed taxes on grain imports, though, for the lower-income Irish citizen, this did little to help. Still, Peel was an outlier in the Parliament, as many British politicians took a lassiez-faire approach and did not want to become involved, saying the Irish landlords should handle famine relief. The landlords sought economic relief instead of famine relief, exporting food made in Ireland.

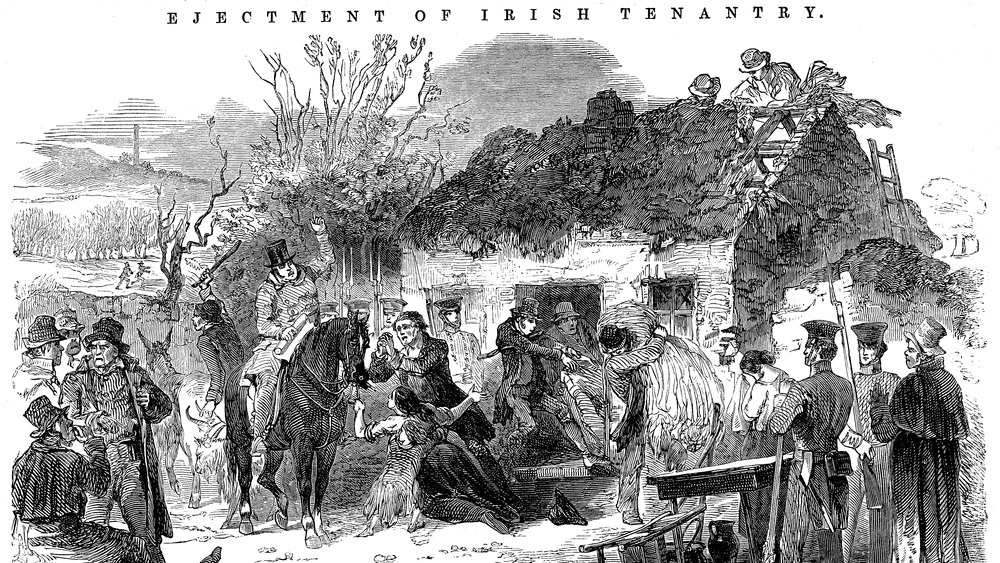

According to the BBC, landlords during the famine evicted around 500,000 people from their homes. Any relief programs created by Great Britain tended to be short-lived, such as the six-month soup kitchen program that fed nearly 3 million citizens a day or low pay public works programs. However, the famine in England became a partisan political topic instead of a humanitarian issue. Peel and others in Parliament decided to combine famine relief with another long-standing political issue.

The Corn Laws

Imagine walking outside and seeing someone had stolen the family's minivan in the middle of the night. Would a proper response be to redo the driveway and clean the oil stain left? Of course not, but do not tell England and Prime Minister Robert Peel, who saw the potato famine as an opportunity to repeal a law he hated, using the Irish as political leverage. According to Digital History, in 1846, England repealed the Corn Laws, which put regulations on foreign grain producers in order to protect English producers. The hope was the free-market trade in England and their colonies would give the Irish access to cheaper and more affordable grain.

However, just like with the lowering of bread prices, the repeal that bought cheaper grain to Ireland did little to help, as the citizens still could not afford the product. In England, the repeal marked the end of Peel's administration. According to Encyclopedia, despite being the head of the Conservative Party, Peel formed a collation that strongly included Whigs, leaving him without much hope to maintain power after the repeal. As reported by Britannica, Peel was forced to resign that June by his own Conservative Party. Despite his shortcomings and failure to understand a proper response to the famine, Peel still understood that the Irish needed direct assistance. While free-market advocates celebrated the decision, the new Prime Minister, Sir John Russell, proved to be as deadly to Ireland as the blight.

Lord John Russell and Sir Charles Trevelyan's policies

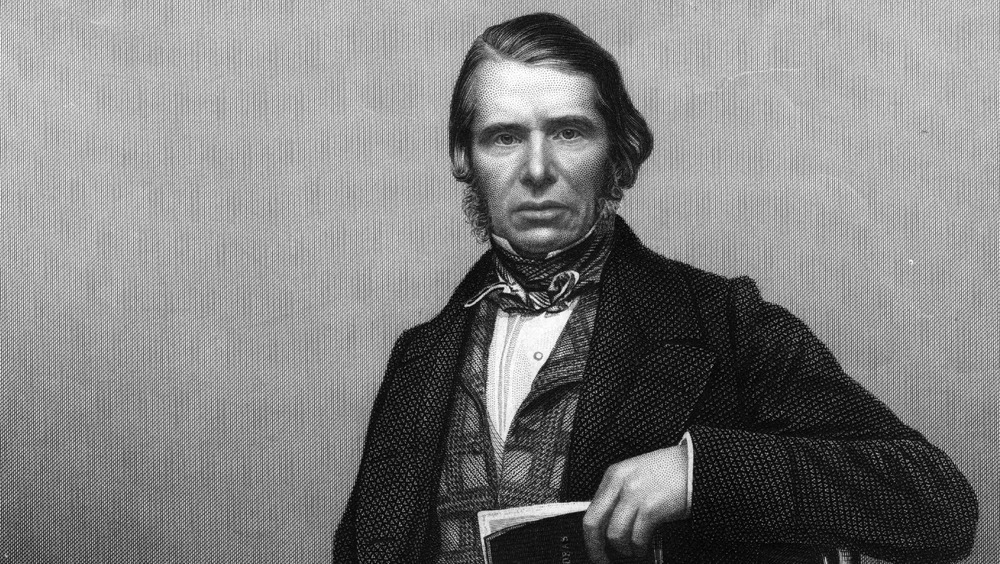

Despite his lack of understanding the depths of the issues in Ireland, Prime Minister Robert Peel was a saint compared to his successor. Once the Corn Laws were repealed, as stated by UK Parliament, the Conservative Party was split and soon, Peel was ousted from his position. Stepping up was Lord John Russell, who put famine relief in the hands of Sir Charles Trevelyan. It was an anti-Irish/Catholic tag team, which led to more suffering in Ireland.

According to the Independent, Trevelyan served in the Treasury under both Peel and Russell. Like many in England, Trevelyan saw the famine as an act of divine will, saying, "the judgment of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, that calamity must not be too much mitigated."

Trevelyan saw the famine as punishment for moral failings, so relief could not come from another nation, but internally. Soup kitchens that fed up to 3 million Irish citizens a day were closed, and cheap, menial labor was instituted. Men, women, and children could be found breaking rocks as if they were in a chain gang for around six pennies a day. These became known as "famine roads." In addition, the British placed famine relief on Irish landlords, who focused more on making profits than relief projects, and evictions skyrocketed. These actions did little for the Irish citizens, and come the next failed crop, Ireland reached its lowest point.

Black 47

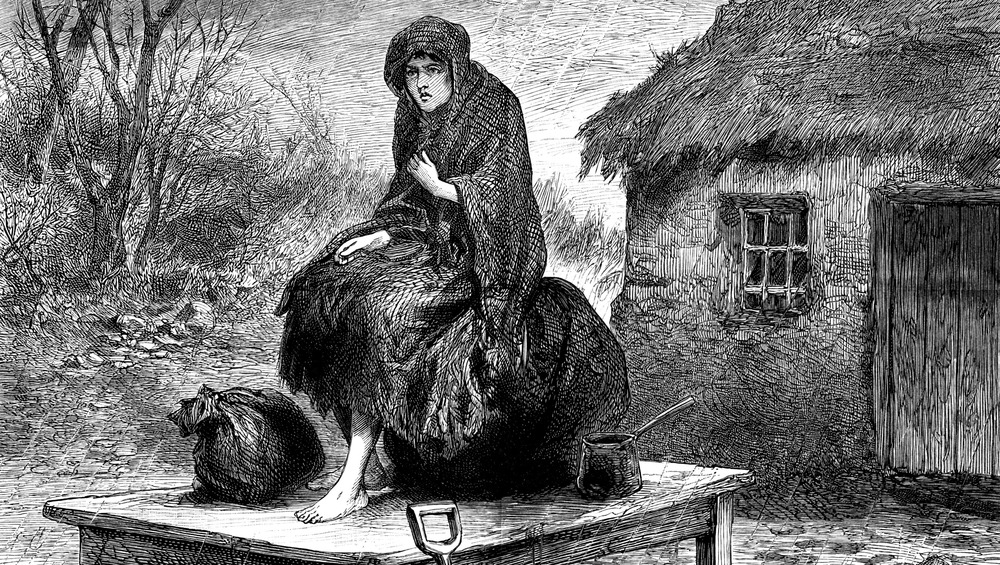

With the policies of Lord John Russell and Sir Charles Trevelyan doing more harm than good for Ireland, the blight disease returning and wreaking even greater havoc on the countryside, and poverty spreading throughout Ireland, 1847 was the worse year of the famine and became known as "Black '47" among the Irish. According to Boston Irish, images of area that were hit the hardest from the famine were reminiscent to ghost towns instead of a village.

Wesley Johnston reports that nearly 100% of the population in the southern and western parts of the country relied on rations. Relying on local businessmen in the country, some Irish citizens were turned away for looking healthy, and others were given fractions of their allotted rations. According to Boston Irish, Irish landlords, in order to turn a profit on their property, simply evicted their tenants and turned their land into a grazing ground for cattle.

The DFA reports that some counties in the western parts of the country lost more than half their population. In one unnerving scene described by Nicholas Cummins, a magistrate in Cork, to a London newspaper, the magistrate described the town of Skibbereen, which was hit hard from the famine.

"In the first, six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead, were huddled in a corner on some filthy straw... I approached with horror, and found by a low moaning they were alive – they were in fever, four children, a woman and what had once been a man."

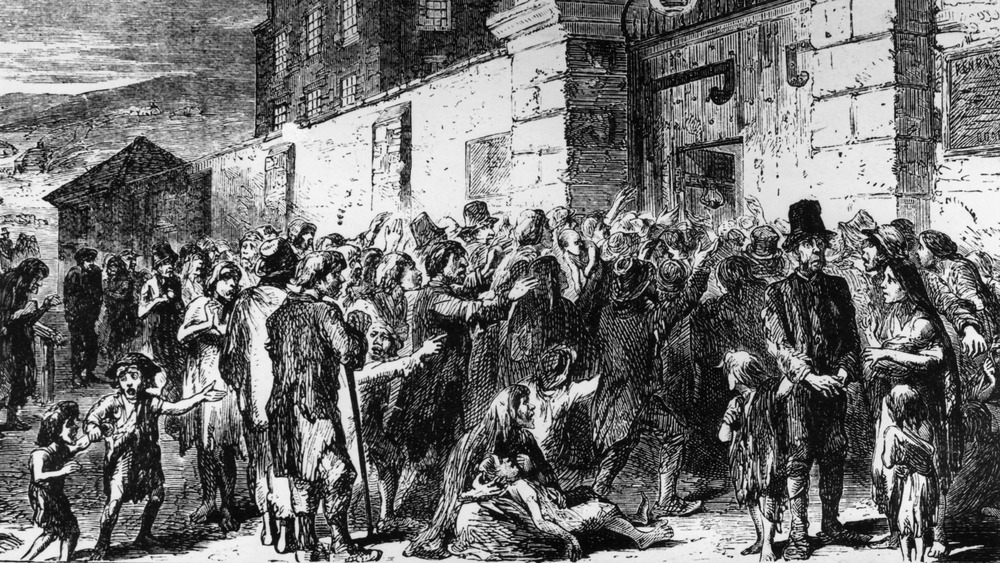

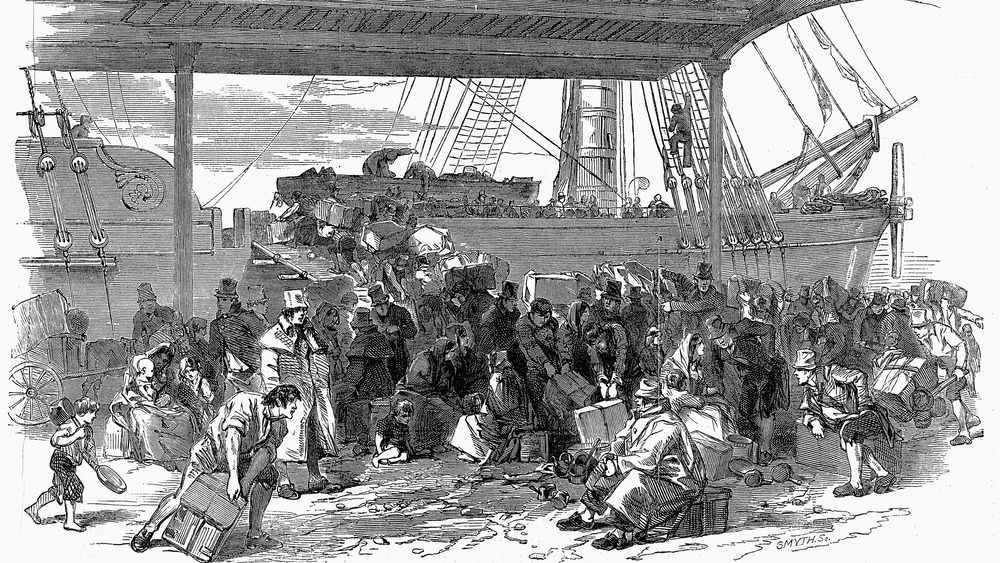

Mass flight

With seemingly no hope in sight, flight to the west and other parts of the world was the only hope for many Irish citizens. According to Extra History, "American wakes" became commonplace in the nation. These were goodbye parties where neighbors and family said their farewells to individuals, leaving for the hope of greener pastures in another country, understanding they were never to see their family and friends again. Still, desperation drove them away. It was even common for Irish citizens to commit a crime in close range of law enforcement to be sent out of Ireland to the penal colony of Australia.

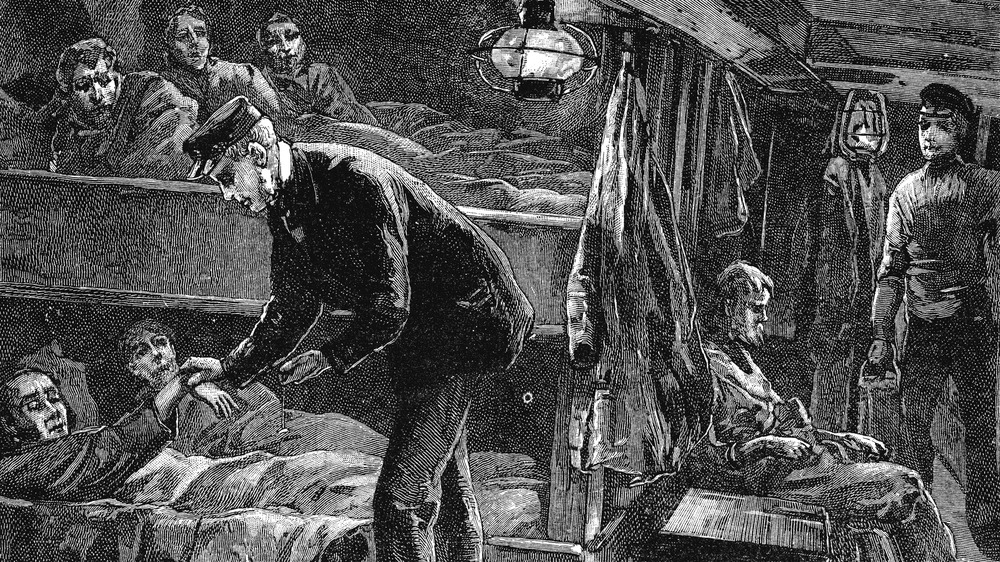

The Constitutional Rights Foundation found that between the years of 1845-1855, more than 1.5 million Irish citizens fled to the United States, and according to the Emerald Heritage, of the 1.2 million Irish immigrants that arrived in Canada between 1825-1970, almost half arrived during the famine years. Despite this, travel could be deadly. The ships that took the fleeing Irish to the west were not meant for passengers. They were timber ships because they carried lumber into the country, usually returning empty to the west prior to the mass emigration. Conditions were horrid to the point that Canadian bound ships were called "coffin ships," as around 30% of the 100,000 Irish immigrants died in 1847 on the ships or in quarantine once they arrived. The United States ships lost around 10,000 passengers. Still, in desperation, the Irish citizens had to take the gamble.

Bitterness towards Immigrants

Unfortunately (and still all too common), Canada and the United States did not welcome their new foreign neighbors with open arms. Instead, political movements sprung out of deep hatred and distrust of the Irish citizen who fled to the west. Still, the Irish came in droves. According to ThoughtCo, the Irish immigrant population prior to 1830 was about 5,000 yearly. By 1850, one-fourth of the population of New York City was Irish. A New York Times article from 1852 found that in a four-day span, 12,000 Irish immigrants arrived in the U.S.

Like Irish landlords, American landlords continued to act as absentee owners and gave their tenants unsanitary and small rooms, as stated in History Place. As the population increased, slums were created, and some immigrants were forced to live in hallways and the backyards of their Irish neighbors. The conditions gave way to crime, as well as diseases, which took the lives of 60% of Irish children before their sixth birthday in Boston alone.

As the population exploded in cities like New York and Boston, anti-Irish and Catholic sentiments exploded in the U.S. Cries of the Irish being dirty, criminals, sex workers, and drunks gained so much ground, a party political party that became known as "The Know-Nothings" gained influence in the country. Riots that burned Catholic churches and other Irish institutions took place in cities such like Baltimore, New Orleans, Philadelphia, and many more.

Old Irelanders vs. young Irelanders

As England continued to ignore the famine or push Irish landowners to solve the issues themselves, a new group of Irish nationalist politicians arose to prominence in the country. Shockingly, when a nation's majority has been beaten down for years, they tend not to think any current system in power can solve their problems. This ran into conflict with the older Irish politicians, and an internal war ensued.

The Old Irelanders was led by "The Liberator," Daniel O'Connell. O'Connell was seen in Ireland by, well, his nickname. He was a longtime politician who abhorred violence in order to gain Irish sovereignty. According to The Irish Story, his message and presence alone were able to combine the more traditional, pacifist Irish politicians and the younger and militant generation. However, in 1843, both Prime Minister Robert Peel and Queen Victoria declared opposition against Irish sovereignty and cracked down on O'Connell's movement. The fraction became clear as the Young Irelanders no longer believed pacifism would bring sovereignty.

The Young Irelanders grew far more militant, as O'Connell's failing health and loss of credibility did not allow him to reunite the two sides. History Ireland states that the February revolution in France in 1848 pushed talks of revolution into action. However, as Extra History explained, Ireland's population had been too depleted from the famine to mount any serious fight against the British, and the quick rebellion was soon quashed, leaving the Young Irelander leaders to flee or be arrested.

Aftermath and legacy

The scars of the Irish Potato Famine can be found throughout Europe and the Americas. As stated in a 2013 article for the Independent.ie, "The Famine was our Holocaust." As the population of the mother country fell, and the Irish population and culture ballooned throughout the west, independence from their English colonizers became a desired reality for the survivors of the famine. A leader in the Young Irelander movement said, "God sent the potato blight but the English created the Famine."

The resentment against the British has stayed in Ireland to this day. According to Extra History, because of their lack of action, a moderate pacifist like Daniel O'Connell would never gain traction in the country again, and future revolutionaries in the country harkened back to the famine when they spoke of independence and British tyranny.

According to Irish Central, contemporary writers and historians have viewed the famine as a genocide enacted by the British, and a large reason for their lack of support in their colonial nation was their anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment. Seeing that Sir Charles Trevelyan, who led famine relief under both Prime Minister Robert Peel and Lord John Russell, is quoted as saying, "the real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the Famine but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people" and rebuking those who tried to do more on the ground, it is hard to argue against the British not holding beliefs in Irish inferiority.