What It Was Really Like Sailing With Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan is a pretty well known name when it comes to the Age of Exploration. The namesake and discoverer of the Strait of Magellan, he's credited with the discovery of the Philippines and gets most of the credit for leading the first circumnavigation of the globe. It's a stacked resume, to say the least.

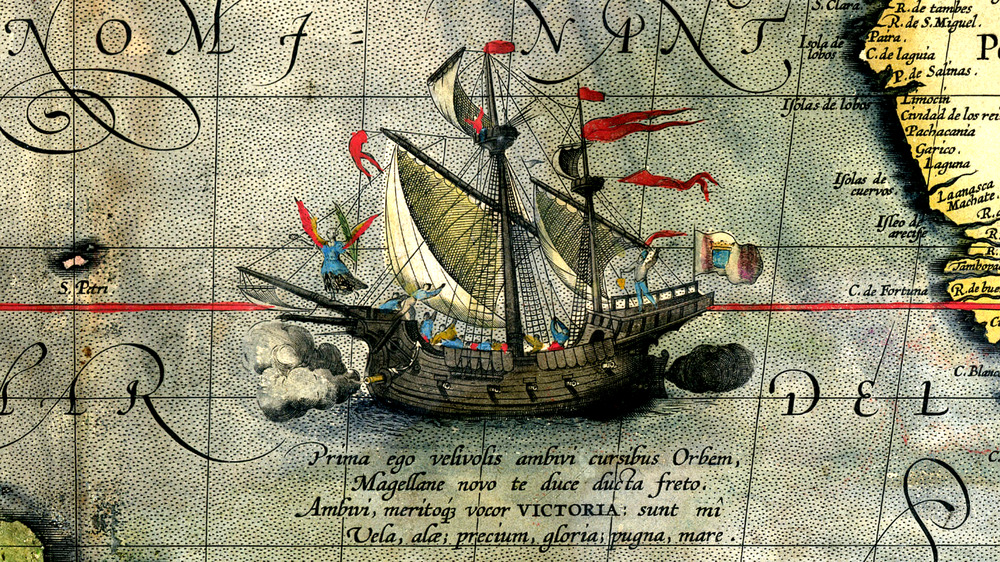

But that doesn't mean being a part of his expedition was smooth sailing, pun intended. His fleet set sail in August 1519 with five ships — the Trinidad, San Antonio, Concepción, Victoria, and Santiago — crewed by 237 men, with the intention of finding a path to the Spice Islands by sailing west. Over three years later, on Sept. 6, 1522, the fleet returned but hardly the same as it'd been when the whole thing started. Only one ship fully made it all the way around the world, carrying a skeleton crew of about 20 men, and Magellan wasn't even among them, dying in 1521. Juan Sebastián de Elcano had taken over as captain for the last part of the journey.

A lot happened over the course of this expedition, and most of it was pretty bad. But what exactly could cut down an entire fleet and crew so dramatically?

Sailing with Magellan meant dealing with bad weather

Maybe it's not that much of a surprise that especially long sea voyages in the early 16th century weren't exactly a piece of cake, but it's also just the general truth. And so, given that, it takes no stretch of the imagination to figure that Ferdinand Magellan's crew — who had to circumnavigate the globe, a long voyage that no one had ever undertaken before — encountered at least a little bad weather.

"Bad weather" is honestly an understatement. From the start, the crew had to deal with awful weather conditions. Near the start of the expedition, the fleet sailed near the coast of Ethiopia and hit a huge storm, documented by Antonio Pigafeta (via Magellan's Voyage Around the World: Three Contemporary Accounts, by Charles Edward Nowell). The tempest lasted for a full 60 days without end, with winds and rain thrashing the ship, and the men truly thought that they would die before the seas calmed. At one point, they even thought that they saw the spirit of St. Elmo appear before them, and they called out, begging for mercy. As if the storm wasn't enough, the waters were also infested with sharks, just to make things even better.

Their troubles with the weather didn't end there, either, because the going was just as rough once they reached the Strait of Magellan, which had its own brand of bad weather, complete with glacier-filled fjords, coarse shorelines, and rough winds.

Magellan's crew had varied interactions with the natives

The history of interactions between European explorers and native populations tends to be really far from positive, frequently leading to death and destruction of varied types, if not long term problems that have reared their heads in the centuries since. Unfortunately, Ferdinand Magellan's voyage wasn't immune to this by any means.

When the crew laid anchor in Guam, the natives saw the ships and immediately boarded them, stealing everything that wasn't tied down (via Princeton). Eventually, the two sides were able to see eye to eye for a while, even getting a little trading done, but that peace wasn't about to last. One of the smaller boats was stolen, and Magellan suspected the native people, sending a raiding party into the village to burn down buildings and kill some of the men — a violent vengeance that seemed like it would set the precedent for dealing with Indigenous people.

Things weren't any better in South America, either. According to Antonio Pigafeta's account, a couple of natives approached them peacefully. Then, Magellan tricked them, giving them some goods before fastening iron manacles on their wrists, threatening to put some on their ankles, too. A kidnapping, plain and simple. Other nearby natives were talked down from interfering and also had their wrists bound before being sent back.

Food was in short supply on Magellan's voyage

According to Princeton, there are over 25,000 islands dotting the Pacific Ocean. That's a pretty huge number, and there's a decent chance that any of them would've been a perfect place for Ferdinand Magellan and his expedition to stop and stock back up on supplies. After all, the voyage across an entire ocean in the 16th century is long, and things like food are kind of necessary to keep things going.

The problem was, the expedition didn't stop at any of those islands. They missed every single one (well, almost — they did come upon what Magellan called the "Islands of Disappointment," and the name sort of says it all). Without any of those stops, food was becoming more than a little scarce.

To put it really plainly, the sailors were starving for "three months and twenty days," according to a report from the time. The biscuits they had on board had turned to powder, filled with maggots that had eaten away the good part of the food, and smelled like rat urine. They were reduced to chewing on pieces of leather that had been left out or else eating literal sawdust. Dead rats actually became the most prized food source anyone on board could find. As the hottest commodity, they came with the price of half a ducat. As if none of that was already disgusting enough, their drinking water had turned a disturbing yellow color. Delicious.

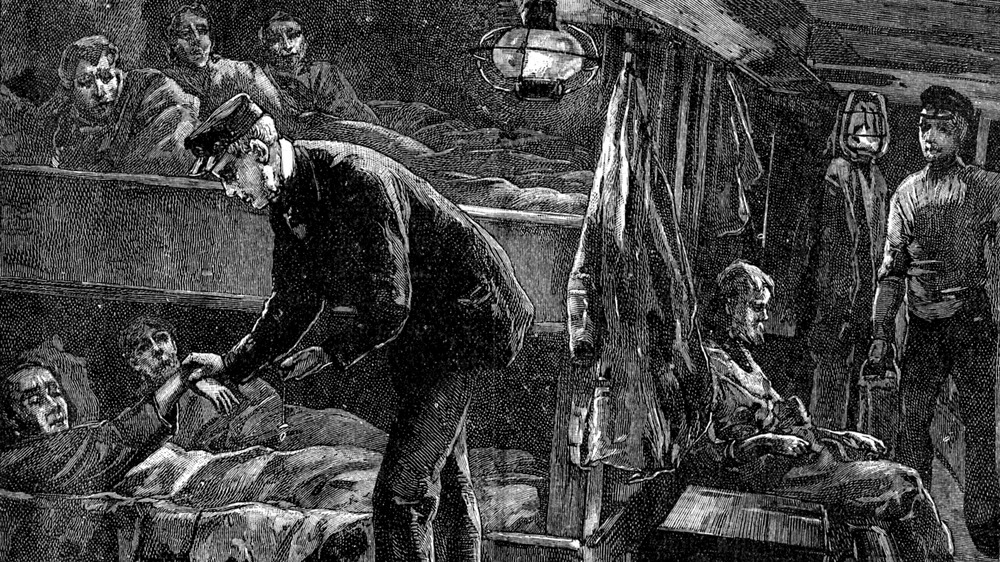

Sickness was an ever-present threat for sailors

Scurvy is one of those diseases that gets tossed around when it comes to pirates and old-timey sailors, but it was a really serious problem from the late 15th century to as recently as the mid-19th century, according to the Science History Institute. In that time, over 2 million people died of the disease, and anyone planning a voyage just assumed that half of the crew would succumb to scurvy. Bleak odds.

Modern science has discovered that vitamin C is the answer, but no one at the time had quite put it together. There were guesses, but no sure solution, and sailors paid for it harshly.

Scurvy was a horrifying disease. It started with just a bit of lethargy, but things would progress from there. Skin started bruising easily, and gums turned spongy as teeth started coming loose. Black spots would spread across flesh, and cutting into those areas just let equally black blood start gushing from the wound. Ultimately, the actual cause of death was usually internal bleeding near the heart or brain, but honestly, the descriptions of the symptoms might be the most horrific part.

Ferdinand Magellan's crew wasn't spared from this terror. Most of the men ended up falling victim to sickness, their gums growing over their teeth, stopping them from even being able to eat. For others, they could see the effects in other parts of their bodies — arms, legs, anything — but on the whole, very few were spared.

Sodomy was punished harshly on Magellan's voyage

In the 16th century, homosexuality wasn't looked upon kindly in much of Europe (to put it very, very mildly). As mentioned by Charles Edward Nowell, sodomy was considered a crime in Spain and was punishable by death. The same rule was meant to be extended to ships and their crew, but that wasn't exactly the reality of the situation. On ships, it was a somewhat common occurrence, and so the punishment was generally overlooked. If anything, the men would get a flogging but not much else.

Ferdinand Magellan wasn't about to let things go that way, though. Not even close. He had the impression that the crew wasn't disciplined enough and had it in his mind to change that, so when one of the officers of the Victoria — Antonio Salamon — was caught with another one of the sailors, Magellan had the chance to make an example of the men.

He decided to put on a full trial, attended by the other captains of the fleet, in which he sentenced both men to death. They were both executed when the ships docked in Brazil.

The crew didn't really like Magellan

During the Age of Exploration, Spain and Portugal weren't exactly on the best of terms, and Ferdinand Magellan put himself in a situation where he wasn't really on anyone's good side. His mostly Spanish crew didn't really trust him, while the Portuguese saw him as a traitor for arranging this voyage with the Spanish king (via National Geographic). In the eyes of the Spanish sailors, Magellan showed a lot of favor to the other Portuguese members of the fleet specifically, and even Antonio Pigafeta just assumed that animosity between the groups came from the fact that Magellan was Portuguese. Granted, that didn't really address the apparent feeling of the sailors that Magellan believed he was above all of them due to the fact he'd gotten the backing of a king.

Juan Sebastián de Elcano made it a point to write about just how badly Magellan had been to work with once he'd returned to Spain (via Princeton). Magellan had already been dead by that point, but some idea of the problems would've been made known before. One of the ships actually turned back to Spain without finishing the voyage, and those sailors had already been talking.

Even outside of just the crew, Magellan didn't have the best of reputations. While restocking in the Canary Islands, Magellan received word that some of the Spanish officers planned to have him killed. The plan didn't come to fruition, but it did put him on edge (via The Mariners' Museum and Park).

Magellan wouldn't listen to the other captains

Even though Ferdinand Magellan was the leader of the expedition, each of the ships in the fleet had their own captain. Juan de Cartagena, Gaspar de Quesada, Luis de Mendoza, and Juan Serrano captained the San Antonio, Concepción, Victoria, and Santiago, respectively, while Magellan captained the Trinidad (via The Mariners' Museum and Park). The problem was, he apparently didn't show them the respect that they wanted.

In general, Magellan kept the route secret from the other captains (via OSU). Understandably, at the start of their voyage, they wanted to get across the Atlantic as quickly as possible, according to Charles Edward Nowell, but for some reason, Magellan decided to sail along the coast of Africa. The other captains weren't informed of this, much less consulted, and when Cartagena went to Magellan with his complaints, he was only told to follow the flagship. Navigation would be left to Magellan alone.

Cartagena in particular was vocal about his frustrations, voicing his opposition to holding an entire trial for an instance of sodomy then also choosing to blatantly disrespect Magellan. A traditional salute was required from the other ships to the flagship — specifically to Magellan — but Cartagena adjusted the wording to offer it to the entire crew. Magellan disapproved, and so Cartagena just completely ignored the salute for the next few days — the only one to be so blunt about his low opinion of Magellan, though the other captains generally agreed with him.

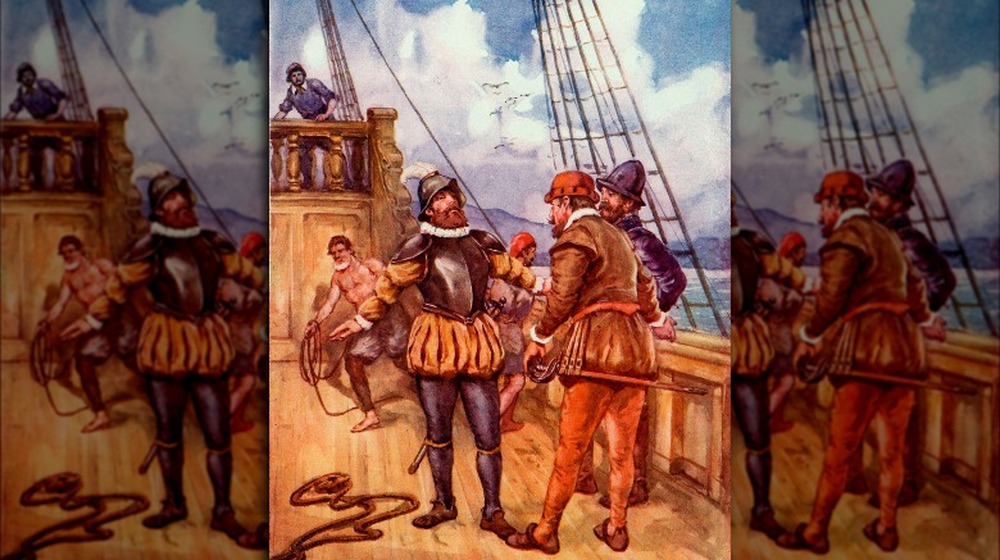

Tensions between Magellan and the crew led to mutiny

To say that relations between Ferdinand Magellan and his largely Spanish crew were going poorly is a massive understatement, so the fact that those tensions eventually turned into mutiny is really no surprise at all. Really, it kind of seems surprising that, given the overall air of distrust and near-hatred, mutiny didn't happen sooner or more often.

Things came to a head on April 1, 1520, at Port St. Julian (via History and The Mariners' Museum and Park). Magellan had invited the captains to breakfast on the Trinidad, only for none of them to show. Juan de Cartagena, Luis de Mendoza, and Gaspar de Quesada were busy getting their respective crews to mutiny (via Charles Edward Nowell). They took the San Antonio and Victoria, and word reached Magellan that they only asked that he change his behavior toward them. Magellan responded by sending a small group to talk to them.

But the group all carried concealed weapons, managing to stab Mendoza in the throat by distracting him with a letter. The mutiny didn't last long after that.

And Magellan had no problem administering harsh punishment. Mendoza had died in the mutiny, but Magellan also ordered Quesada to be beheaded, then both of their bodies quartered (via National Geographic). Cartagena was left stranded in South America when the fleet left to continue the trip.

The number of ships in Magellan's fleet dwindled

When the fleet first set out from Spain, it was made up of five ships, but most of those ships met unfortunate ends — or at the very least didn't make it around the globe. The first to fall was the Santiago, which wrecked during a scouting mission (via The Mariners' Museum and Park). The San Antonio tried and failed to make a stealthy escape while much of the crew mutinied at Port St. Julian, according to Charles Edward Nowell. Later, finding themselves separated from the rest of the fleet in the Strait of Magellan, the crew decided to take over the ship, turning around to head back to Spain.

The Concepción fell in the Philippines (via Princeton). Understandably upset by his situation, Ferdinand Magellan's slave Enrique conspired with some of the natives to orchestrate a massacre of the European crew at a feast. Some of the crew did escape, but the attack left them really short-staffed, and the Concepción was burned because there weren't enough people to man all the ships.

Only the Trinidad and Victoria actually made it to the Spice Islands, but by that point, the Trinidad badly needed repairs. The Victoria went on ahead (eventually making it back to Spain), but when the Trinidad set sail again, it was captured by Portuguese ships. All of its supplies were likely confiscated and the crew imprisoned on Ternate, where the Trinidad wrecked and found its final resting place.

Magellan forced the crew into an unwanted battle

Ferdinand Magellan didn't actually make it all the way around the world during the famous circumnavigation that's named after him. He only made it as far as the Philippines. But for all the things that could've killed him, his cause of death was far from natural and entirely brought upon himself.

While in the Philippines, Magellan hit it off pretty well with one of the native chiefs and was told to go visit an ally, Raja Humabon, on a neighboring island (via Princeton). Magellan and Humabon also became close — Humabon ended up convincing the entire village to convert to Christianity, and Magellan wanted the neighboring islands to pledge their allegiance to Humabon. That didn't go over well, and, wanting to impress his new friend, Magellan ordered his crew to fight one of those other tribes.

By no means did the crew want to do it, but they had no choice. The ship had to anchor far from the shore, and a group of 60 men had to wade through the water to even reach the 1,500 natives already shooting at them with arrows (via The Mariners' Museum and Park). It makes sense that they weren't a fan of the odds.

Magellan himself was hit during the battle, and the crew retreated, leaving his body behind (possibly intentionally), according to National Geographic.

But Magellan's voyage had some good come of it

Fortunately, for all the bad things that happened, there were some good ones to come of the voyage. At the most base level, the voyage did accomplish what it was meant to — finding a way to the Spice Islands by going west and returning with 381 sacks of cloves, making the trip profitable (via Princeton).

But it did more than that, too. Ferdinand Magellan and his crew became the first Europeans to ever see the Pacific Ocean from the Atlantic. Magellan is even attributed with coining the name (via History). After hard sailing through the rough Strait of Magellan, the Pacific was amazingly tranquil by comparison, hence the name sounding close to words like "pacify." And the name has stuck for centuries — that's a cool legacy.

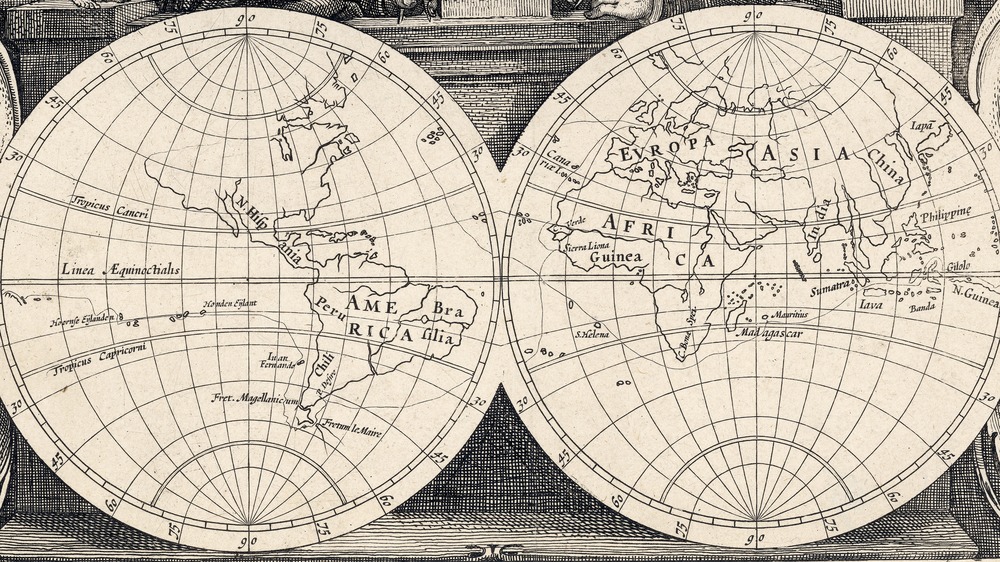

Plus, the journey had big scientific and intellectual impacts, too. No one at the time could've known the size of the globe. Everything was just speculation and guesswork. But the voyage started by Magellan changed that. Cartographers finally had a solid idea of just how large the world was, based on real data, and an entire new ocean could be charted. Whether Europeans having access to the Pacific was ultimately positive or negative — the chieftain who killed Magellan is hailed as a national hero in the Philippines, because the voyage ultimately brought European colonization on its heels (via National Geographic) — it did happen, and history was shaped as a result.