Great Smog Of London: The Tragedy That Killed Thousands

Let's say that you're strolling down the street, and a dense fog surrounds you. Not only can you no longer see to the street corner ... you can't see just a few feet past you. As you walk, you realize that you can no longer even see your feet. Above you, birds are slamming into windows — harsh and abrupt. You can hear the sounds of cars crashing at an intersection that is no longer visible. And suddenly, you plunge directly into the cold waters of an unseen river.

This isn't fiction, and it isn't fantasy. Rather, it's a description of a historical event. Almost 70 years ago, the "Great Smog of London" descended upon the city and its approximately eight million residents. And somehow, everyone was more or less okay with it.

To be clear, the Great Smog of London was a tragedy. By the time it was over, thousands of people were dead. While British resilience may be the stuff of tales, the smog was all-encompassing. Even more problematically, there was really nothing anyone could do but wait for it to be over.

The Great Smog of London happened on Friday, Dec. 5, 1952

It had been unusually cold in London, prompting many to burn additional coal. A combination of coal-burning and unique weather events led to smoke accumulating on top of the city — with nowhere to go. According to The Guardian, what followed was five days of near-complete darkness, with people barely able to see their own feet as they walked.

It was a perfect storm of events. If the wind had picked up even a little, the smog wouldn't have sat over the city. And if people (and power plants and industrial buildings) hadn't been using so much coal, the smog wouldn't have been so great. But the Great Smog of London, like many similar events, was caused chiefly by a temperature inversion. Cool night air remained cool due to the chilling effect of the dark smoke. As hot air rose, the cool air continued to linger close to the ground, without a breeze to move it.

Regardless of the reasons behind the smog, the city ground to a halt. Because of the low visibility, cars couldn't get to where they were going. Soon, even pedestrians weren't able to walk — at night, the incandescent bulbs that usually lit the way were useless. All they could do was wait for the smog to let up.

The term smog itself was invented in London in the early 20th century

Smog is not a natural occurrence. The word itself is a portmanteau of "smoke" and "fog," likely invented by a Londoner sometime in 1905. And while smog can seem very much like either fog or smoke, it can be more dangerous than either.

Smog occurs when water vapor connects with various pollutants and produces low-hanging clouds. Thus, it's a modern creation: It's something that has come about due to the proliferation of air pollution. And it creates a thick, hanging cloud that has the worst elements of both smoke and water.

Air pollution in London was already quite bad at the time of the Great Smog. According to Britannica, most were used to it. It was the "Great Smog of London" after all, not the "First Smog of London." And while the term "smog" might date back to 1905, complaints about air pollution in London date back to the 1280s.

What was so unusual about the Great Smog wasn't that it existed but rather that it continued for such a significant duration. Most smog would dissipate or just remain as a low-level, low-grade nuisance. But because of the lack of wind and the temperature differential, the Great Smog persisted for nearly a week.

The Great Smog lasted a total of five days and killed anywhere from 4,000 to 12,000 people

Accounts vary on how many people died from the smog. The BBC estimates that it would have been about 12,000 people – while at the time it was estimated to be closer to 4,000. It's difficult to say how many people ultimately died, as not everyone may have died immediately.

A later study noted that there was a 19.8% increase in the chance of developing childhood asthma among those who were exposed to the Great Smog during the first 12 months of their life. Further, a 7.9% increase was found in those who were in the womb during the event. Such damage could contribute to increased mortality rates even among those who survived.

In addition to those who died later, it's probably impossible to know how many people died from environmental complications. According to the BBC, 35 vehicles were involved in a single crash, and multiple people were injured in other collisions. It would be hard to list the deaths caused by smog-shrouded mishaps.

What is known is that it's not less than 4,000: The 4,000 number is based on those who died from the smog, likely those who died from immediate lung complications and other issues directly related to the pollution.

No one in London panicked during the Great Smog

Perhaps one of the most interesting things about the Great Smog of London is that no one panicked.

First, they were used to the smog. In fact, Londoners were so used to heavy fog that they had their own term for such events: "pea-soupers." This incident of smog clearly lasted longer than normal — but during that first day, it's possible that no one worried at all. During the second day, they may have thought it unusual, and by the third, they might have started to worry.

But The Verge raises an interesting point – even if they were concerned about the duration of the fog, the general public likely didn't realize how many people were dying. Because there was no central system of fast news (like social media), people weren't kept apprised of overall trends. Instead, while they might have individually seen a friend, family member, or neighbor dying, they weren't able to connect it to a larger, environmental issue.

Today, we are intensely aware of everything that happens. Because of that, it's easier for us to see trends. (Sometimes, we might even see trends where none are there.) We know, for instance, how many people have died from COVID-19 in our country, state, and county. But in the past, these numbers simply weren't as readily available, and it was difficult (if not impossible) to know exactly what the trends were.

The Great Smog of London was acidic, too

As if smog that blots out the sky wasn't enough, there may have been an acid component as well. Some scientists believe that acid could have contributed to the deaths during the Great Smog. While this wasn't something that was discussed at the time, it has been explored by scientists later.

According to a study by researchers at Texas A&M, it's possible that high levels of acidity essentially created something akin to clouds of sulfuric acid, further injuring those who were exposed to the pollution. This is something that has also been seen in air pollution in China. So, in addition to suffocating, people were inhaling acid as well.

Acid rain has always been connected to air pollution. When burning fossil fuels, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides are introduced into the atmosphere. These chemicals then mix with water, forming acids that fall to the ground as rain. In the case of the Great Smog, the acids would have been caught in the humidity of the smog itself. Thus, the Texas A&M study could answer a question — how the London smog was able to kill so many people. Theoretically, it wasn't just "smog" — it was a uniquely dangerous and suffocating cloud of acid.

Government initiatives were at least partly to blame for the Great Smog

Before the Great Smog, London had been industrializing rapidly, and the government was exporting much of its coal for money. The government chose to ship out much of its superior coal stock, leaving its own citizens with coal that contained greater amounts of sulfur.

History.com notes that the government didn't take action very quickly during the Great Smog because fog and smog were so frequent. Of course, it's possible that there would have been little the government could have done at the time. At minimum, they may have been able to discourage residents from continuing to burn coal on their wood-burning stoves.

Even if the coal hadn't been of reduced quality, it's possible, if not likely, that the Great Smog would still have occurred. Coal is known for being one of the dirtiest fuel sources by its very nature. While various clean coal initiatives have tried to reduce the amount of pollution that coal produces, few have been successful — trying to clean coal renders it far less efficient. For one, cleaning coal requires that a lot of additional energy be expended to wash the coal or clean the air.

Citizens, as well as the government, were to blame for London's air pollution

It wasn't all the government's fault. According to The Guardian, London's citizenry had pushed back against many initiatives for reform over the years. Some citizens believed that these initiatives would reduce jobs. Others were wary of getting rid of open fireplaces — they thought it could cause disease by creating "stagnant" air. And health officials didn't really take the issue seriously. After all, they had been living with it for some time.

It's long been believed that people would get sick because of stagnant air. And it's not incorrect. Today, we know that stagnant air without filtration can promote the transfer of bacteria and viruses and increase the potential for infection. It's not unlikely that individuals had noticed that people would get sicker during the stuffy winter months, though they might have attributed it to a "miasma" in times past.

So, citizens were between a rock and a hard place (or a humid and a smoggy place). They could close off their vents and reduce air circulation, but that would only make their families ill. Failing a more comfortable option, they continued to vent their plumes of smoke out into the surrounding environs.

Not everyone died because of the Great Smog itself

According to The Guardian, many of the people who died during London's Great Smog didn't die from the smog itself. Instead, they died because they had fallen into the River Thames and consequently drowned. Due to the low visibility, many pedestrians couldn't even see their feet. Before they knew it, the river (despite being stationary) was upon them.

This highlights another issue with the Great Smog: those who died from mishaps rather than the smog itself. While many people stayed home during the Great Smog (and traffic was largely at a standstill), there were still people who were out and about.

London, being such a large city, had its share of pollution-based mishaps before. During the Great Stink, the River Thames flooded with sewage and dead animals, causing all manner of distress and illness. In fact, it was partly the Great Stink that encouraged Londoners to keep their homes well-ventilated — they believed that the odor from the Great Stink could potentially kill them. But these were the growing pains of a country with a large and increasing population. Recently, London's population has actually started to decline, for the first time since 1988.

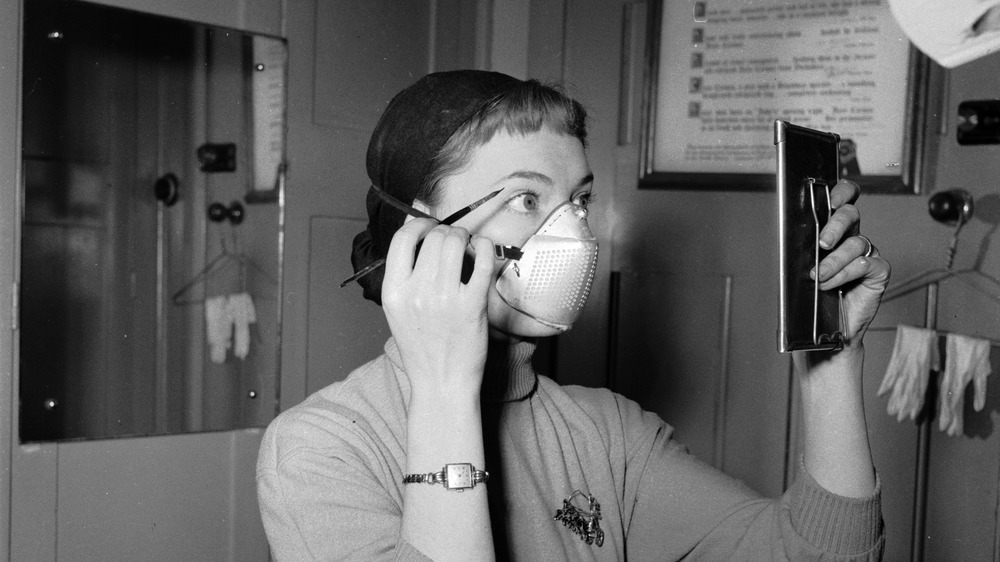

People wore masks during the Great Smog

While it may have seemed unusual when people started wearing masks during the COVID-19 pandemic, Londoners were once quite used to it. Many pictures of the London Smog, some featured in Forgotten History, show people wearing masks to protect against the pollution. And, of course, there are many in China today who wear masks for the same reason: Masks, particularly N95 and KN95, are known to protect against air pollution.

Both cloth masks and medical masks can be seen in photos of the Great Smog, and they may have both cut down on the amount of smog being taken into the lungs and improved the breathing comfort of those who were being subjected to it. Some people even experimented with bowls that went over their head!

While much of the city had shut down, there were still people who needed to go out. Even so, photos show people wearing masks indoors, as the smog could get almost anywhere.

People weren't the only ones who died during the Great Smog

In addition to people, cattle were lost to the Great Smog. History.com notes that 11 heifers asphyxiated in the smog, and some breeders took to improvising gas masks for their cattle. According to NPR, the dead cows' lungs turned out to be black.

The lungs of the cattle were undoubtedly also an indication of what happened to the lungs of the people who lived in London at the time — and those who continue to live in areas with high air pollution. Long-term air pollution can cause damage to lungs, both for people and for animals, and that's something to think about for those in high-pollution zones today.

During the Great Smog, birds also suffered from the low-lying smog, which caused them to crash into buildings. As for the cows, it's possible they would have been fine being eaten — but it's no wonder that people decided to pass.

The Great Smog is still considered the worst air pollution event in London — but it's not alone

There have been several other deadly, pollution-related fog events in London, but according to the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, the London Smog is considered to be the worst. Still, it's not alone. Globally, there have been numerous instances of dangerous smog, such as the St. Louis Smog, Meuse River Valley Smog, and the Donora Smog.

The Donora Smog occurred in 1948, killing 20 people and injuring another 6,000 — incredible numbers considering that the population of Donoro, Pennsylvania, was only 14,000 at the time. The Donora Smog occurred because of emissions from the local plant. Due to a temperature inversion, the smog was trapped over the city just as with London. The smog lasted for five days.

Similarly, in 1930, the Meuse River Valley Smog killed up to 60 people in Belgium. Again, it was a combination of industrial air pollution and climate issues: The air settled rather than moving. The St. Louis Smog of 1939 also occurred due to a temperature inversion. It didn't kill anyone, but it definitely lowered visibility.

The Clean Air Act was passed four years after the Great Smog of London

The Clean Air Act of 1956 was passed following the Great Smog of London, governing domestic and industrial emissions. The act included prohibitions of dark smoke coming from chimneys and requirements for new furnaces being manufactured. Despite this and other such measures, The Guardian reports that about 18,000 people every day still die from air pollution across the world.

The Great Smog of London was a perfect storm of events. It was cold, so they burned more coal. The government had been selling its best coal, so the coal that was being burned was even dirtier than normal. And a temperature inversion had occurred, so the air had settled. Nevertheless, it would never have happened if the sulfurous coal wasn't being burned and if there had been a way to control the smoke.

The 1956 Clean Air Act sought to make it much harder for these situations to align by reducing the amount of coal burned and ensuring that the newer furnaces were better-equipped to filter it. Today, coal accounts for very little of the energy produced in the United Kingdom, and Britain has gone entirely coal-free for chunks of time — a significant boon for the environment. Still, some believe that air pollution remains one of the UK's biggest health threats.