What It Was Like To Be A Worker On The Transcontinental Railroad

Once upon a time, railroads were a big deal. They still are in the world of manufacturing and industry, according to the Association of American Railroads, but this mode of transportation once dominated the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. Rail lines provided a vital network not just for moving goods but also people across a growing nation.

In the first half of the 1800s, however, people who wanted to travel cross-country had to do so by wagon or horseback. While that established the now legendary Oregon Trail and other routes, moving across the U.S. at what amounted to a snail's pace was, frankly, agonizing. Life in the American West was also pretty harsh and sometimes even downright dangerous, even if you were only passing through on your way to California.

According to History, things really got moving in 1862, when Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act that formed the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad Companies. Central Pacific would begin in Sacramento, California, while the Union Pacific company would start in Nebraska. Over the seven years it took for the two to meet at Promontory, Utah, the companies would compete head-to-head. But who built the railroads? While company heads and contractors were crowing about their progress, someone had to actually put down the railroad ties, blast their way through mountains, and brave the elements. The story of what it was like to be a worker on the Transcontinental Railroad is both dramatic and historic.

Transcontinental Railroad workers were always out in the elements

The Transcontinental Railroad was, in short, a big deal. It presented a huge economic and cultural opportunity for the 19th century United States with the possibility of connecting the eastern and western halves of the nation with a relatively fast-moving rail network. According to the Library of Congress, the first idea of a railroad connecting the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the U.S. was floated in the 1840s. Yet, construction on the lines didn't begin in earnest until the 1860s.

By the time workers actually began to lay track for the two branches of the line, termed the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads, investors wanted things done quickly. Because of this drive and of the harsh conditions of the region, workers were subject to pretty intense environments.

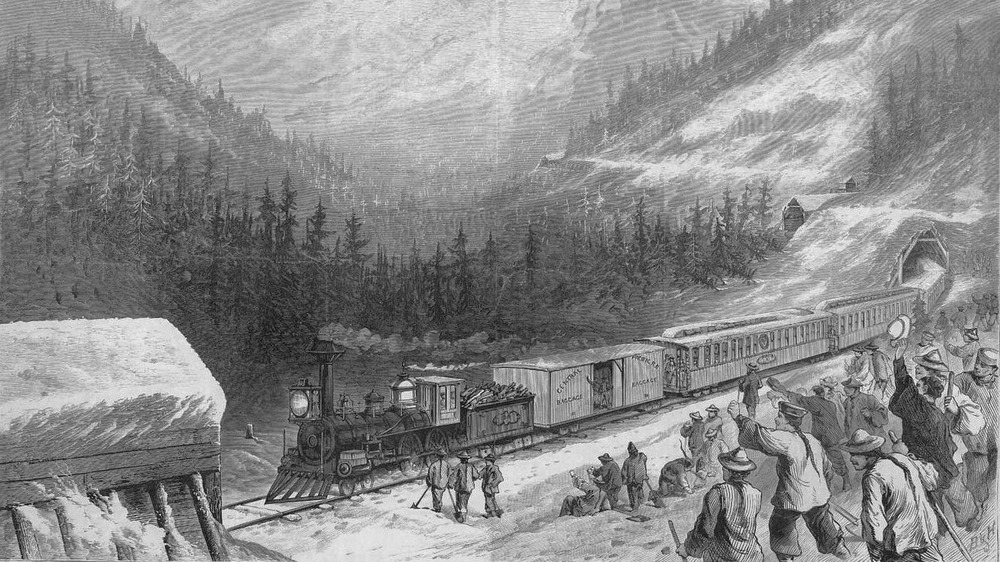

As the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project reports, laborers could expect a wide variety of elements, from the deep snows of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California to the incredible heat and dry climate of the southwestern deserts. This all took place in an era before heavy industrial equipment became common, meaning that someone might find themselves laying railroad tracks in a snowstorm with only a pick and shovel in their hands.

The earliest workers on the Transcontinental Railroad were Irish immigrants

At first, the tough, backbreaking work of establishing the Transcontinental Railroad went to Irish immigrants. As American Experience reports, by the year 1865, the Central Pacific railroad needed to hire thousands of men. Yet, despite the number of people living in the region at the time, contractor Charles Crocker — who would go on to feature in some of the biggest tales of the Transcontinental Railroad — could hardly keep more than 800 workers on the roster.

That may have been due in part to rampant racism, both against the Irish and the Chinese workers who would soon join them. According to History, 19th century America was not kind to immigrants fleeing the Irish potato famine of the 1840s. The Catholic Irish rankled Protestants already living in the United States, while "nativists" and other anti-Irish people pushed stereotypes of sub-human, lazy, and riotous Irish people. Like all stereotypes, the charges lobbied against the Irish were largely untrue or else due to systemic neglect.

Yet, the railroad managers of the Central Pacific fell back on assumptions that said the Irish would only spend their money on alcohol and become unruly and difficult to direct. These attitudes would only make it all the more difficult for workers and bosses alike.

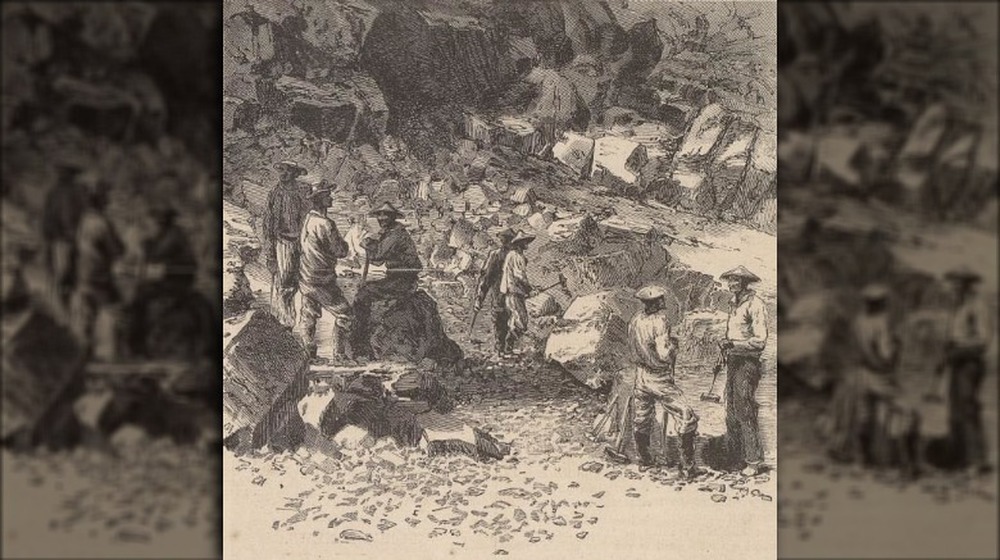

Chinese immigrants were hired to work on the Transcontinental Railroad despite racism

Officials with the Central Pacific railroad were initially reluctant to hire non-white laborers from China. As per PBS, people began to immigrate to the United States from China in the 1850s, avoiding economic troubles in their home country while perhaps hoping to benefit from the gold rush gripping the western U.S. Yet, once they arrived, they were subject to racism and nativist suspicion, though some took advantage of their typically low social status and hired them as cheap workers. Eventually, Congress would pass the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, banning immigration from China. The act would not be repealed until 1943.

However, in the 1860s, Chinese people were still traveling to the United States and the Central Pacific railroad was facing a severe labor shortage. The National Park Service reports that contractor Charles Crocker proposed hiring 50 Chinese workers as an experiment. Though racist assumptions led some to believe that the Chinese men hired would be too weak and feckless for the job, the laborers proved everyone wrong. In fact, they were as hard-working as anyone else and produced high-quality work at an exceptional pace.

Chinese workers even had a healthier diet and drank tea made with boiled water, which helped them avoid diseases that plagued other workers. They held one more benefit for the penny-pinching managers, too: Chinese workers were paid at significantly lower wages compared to their white counterparts.

Transcontinental Railroad workers were in constant danger from explosions

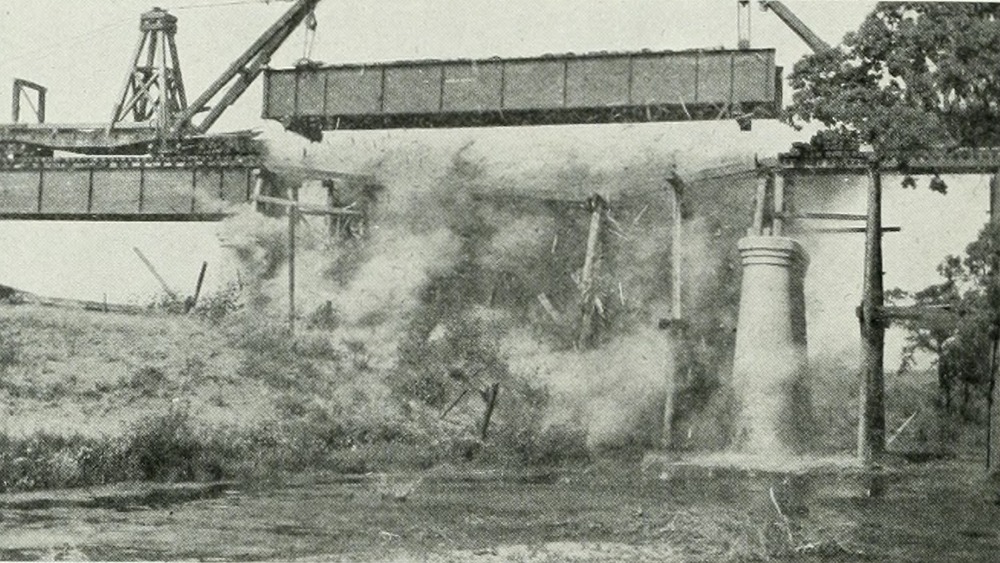

Though much of the work on the Transcontinental Railroad was completed with hand tools like pickaxes and shovels, some obstacles needed a stronger approach. Geographic features like mountains often required the workers to tunnel through the rock, meaning they needed to use explosives.

Of course, in a time before occupational safety standards, a workplace full of dynamite and nitroglycerin wasn't exactly a safe place to be. Between that and the often poor communication between foremen and their workers, which included potential language barriers, horrible accidents did happen.

One Chinese laborer, quoted in Chinese American Voices, recalled a particularly horrifying incident that occurred while he was working for the Union Pacific railroad line. A team set 20 explosive charges to break through some rock. Only 18 went off, but the unaware foreman sent his team into the space to continue working. As the laborers went in, the two remaining charges went off. "Chinese bodies flew from the cave as if shot from a cannon," the worker recalled. "Blood and flesh were mixed in a horrible mess. On this occasion about 10 or 20 workers were killed."

In 1869, Transcontinental Railroad workers laid 10 miles of track in one day

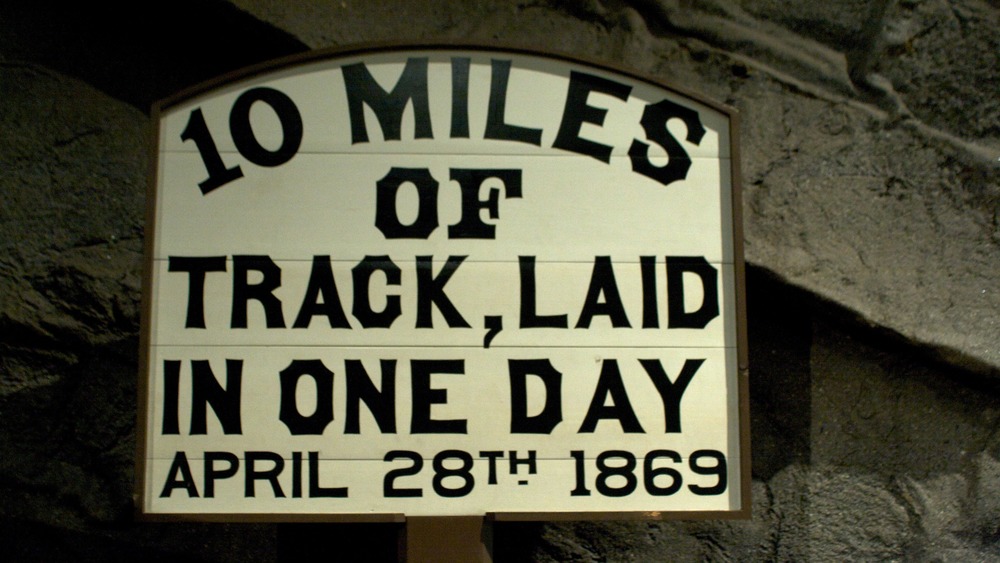

According to NBC News, the two tracks simultaneously being laid by the Central Pacific Railroad Company and the Union Pacific Railroad easily led to serious competition between the two companies. It was a useful tool for the managers, who surely liked to see the track grow to its completion. To that end, in 1869, a more formalized competition began.

As the Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum reports, the two companies entered into a contest to see who could lay 10 miles of track in a single day. It was an escalation from earlier contests, starting with six miles of track in a day, set by Union Pacific. As the situation developed, Central Pacific's chief contractor, Charles Crocker, declared that his teams could readily hit 10 miles in a day.

Easy for Crocker to say, but this proved to be incredibly hard work for the laborers. The process took considerable planning, not to mention the preparation of track materials that came out to an estimated 4.4 million pounds (via NBC). Yet, despite the huge amount of work and the rough conditions of Utah's high desert, the Central Pacific laborers laid 10 miles and 56 feet on track near Promontory, Utah on April 28, 1869.

Chinese workers led a strike to protest wage inequality

As the Transcontinental Railroad continued onward, it became plain to everyone that the Chinese workers were a vital part of the labor force building the tracks. According to PBS, executive E.B. Crocker complained that other companies, including mining operations, were siphoning away their hardworking immigrant workforce. His brother, Charles, who was also the project's chief contractor raised monthly wages from $30 to $35, but this move, instead of drawing in new workers, would have unintended and dramatic consequences.

On June 25, 1867, Chinese workers dropped their tools and began to strike. The men had noticed that white laborers were often given more skilled work, regardless of their background, and were paid more. As the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project reports, this would be the most sustained strike in the process of building the railroad. Some strikers reported that overseers had forced them to remain with the company, even when they attempted to find work elsewhere.

Though the strike was nonviolent, the lack of labor endangered government subsidies that funded the company. Charles Crocker blocked the delivery of food and supplies to the camp. After eight days, the Chinese workers faced starvation and violence from a group of white men deputized by the local Sheriff. Though they didn't receive the $45 per month pay raise they had wanted, History reports that working conditions did improve soon after, as the company had realized how vital the Chinese laborers were to the railroad.

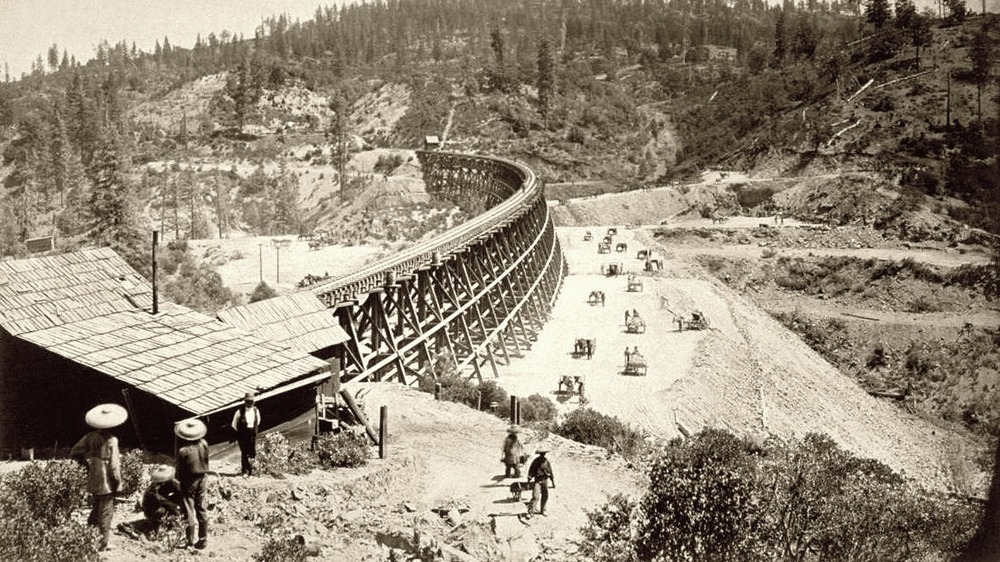

The Sierra Nevada mountains presented a huge obstacle to the Transcontinental Railroad

It's hard to understate just how much of a challenge the Sierra Nevada mountains of California presented to the workers of the Transcontinental Railroad. Running alongside the eastern border of California, as per Britannica, the Sierra Nevadas are largely made out of granite that can be tough to clear, even with modern equipment. During the 1860s, the engineering demands of creating tunnels and laying railroad track through the mountains was even more difficult.

PBS reports that the early snows of 1865 stymied the Central Pacific railroad's attempt to finish the "Summit Tunnel." Workers were generally blasting their way through at an agonizingly slow rate with the use of black powder. Laborers would detonate charges and then use a modified locomotive to haul debris out of the forming tunnel. Later, a British chemist named James Howden was brought to the site in February 1867, where he would mix nitroglycerin. The preparations made by Howden were more efficient and had greater force than the black powder, helping the work to move faster.

Workers also had to contend with harsh winters in the 1865-1866 and 1866-1867 seasons. At Summit Tunnel in the winter of 1866-1867, the snowpack accumulated to 18 feet in a season where teams had to contend with 44 individual storms.

Avalanches could take the lives of Transcontinental Railroad workers

The weather of the Sierra Nevada mountains was one of the greatest and most deadly obstacles to face workers as they slowly pushed their way through the granite rock into the interior of the United State. According to PBS, avalanches routinely cut down entire groups of workers The remains of some unfortunate workers wouldn't be found for months following the tragedy in question.

The Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project reports that the threat of avalanches was ever-present. Supervisor James Strobridge said that "camps were carried away by snowslides, and men were buried and many of them were not found until the snow melted the next summer." One particularly bad avalanche killed 20 men. Even those who didn't find themselves struck by a sudden snow slide could still be temporarily buried by the blizzards that regularly hit camps and work sites. During the worst of the weather, laborers were forced to dig passages into the tunnels simply to work, with the longest such passage reported to be 500 feet long.

All told, it's estimated that avalanches, along with the other hazards of the Transcontinental Railroad, took the lives of anywhere from 50 to 2,000 Chinese workers. As Central Pacific did not track the deaths of its workers, however, we'll likely never know the true mortality rate for railroad laborers.

Managers began competitions between laborers to get the work done faster

Central Pacific primary contractor Charles Crocker, like other managers of this era, set up competitions based on racial and ethnic differences. The idea, according to the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, was that laborers would be incentivized to work even harder in an effort to prove themselves and instill a sense of pride. However, it also produced situations that, at least to modern observers, created unnecessary tension.

One such competition took place in the Summit Tunnel deep in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Crocker recruited miners from Cornwall, England, then well-known for its mining industry, to come out to the site and move the work along. It was widely believed at the time that Cornish miners were amongst the best in the world, and so would have been believed to be uniquely qualified to tunnel through the California mountains. The Cornish men, who traveled from nearby silver mines in Nevada, were set going one direction in the tunnel. Chinese workers were placed going in the opposing direction.

Crocker later reported that the Chinese laborers "without fail always outmeasured the Cornish miners [...] there it was hard work, steady pounding on the rock, bone-labor."

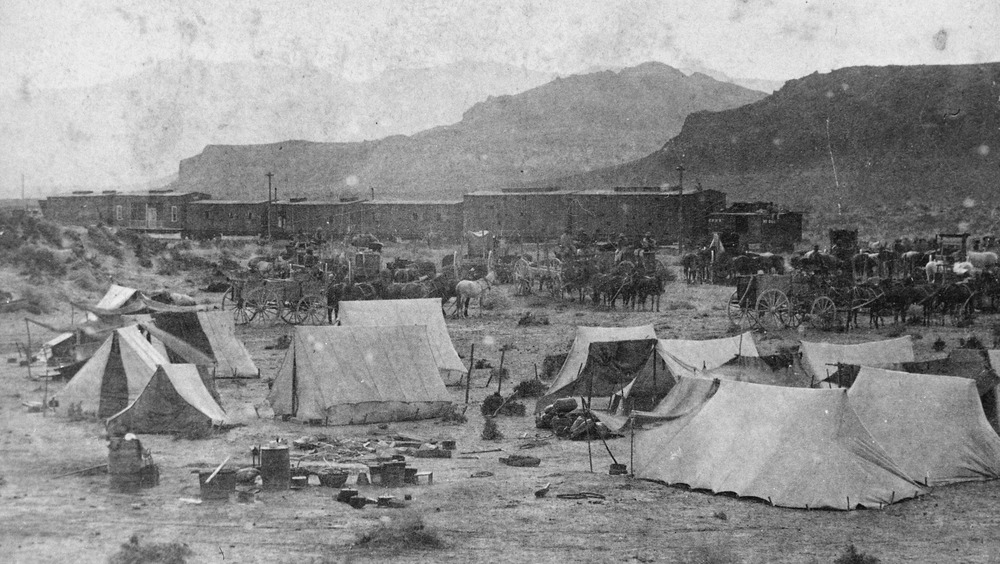

The Nevada desert presented a new challenge to workers on the Transcontinental Railroad

Many of the workers on the Transcontinental Railroad, and especially those working under Charles Crocker and the Central Pacific, must have breathed a sigh of relief as they made their way out of the harsh environment of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. Yet, as they descended the slopes towards the high altitude deserts of Nevada, laborers would face new and equally intense working conditions.

As Ghosts of Gold Mountain reports, the desert was a harsh taskmaster all of its own. Many Transcontinental Railroad workers were effectively stuck there from 1868 to 1869. Though the mountains were behind them, Central Pacific workers still had to navigate a land that required them to grade areas to keep track level, and sometimes figure out just how they were going to get a train to cross one of the canyons that dotted the landscape.

According to the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, workers at least gained a "hot-season" pay raise for working in Nevada during the summer. Yet, conditions were still intense. Many collapsed under the heat, which could reach a maximum of 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Meanwhile, water became a desperately needed resource. When natural sources like rivers became inaccessible, trains would bring water and other supplies to the end of the track. Engineers also ferreted out hidden freshwater springs in the area, employing a network of pipes and storage tanks to stave off dehydration for the laborers.

Native Americans both troubled and helped Transcontinental Railroad workers

Though no major clashes were recorded, workers routinely fretted about hostile Native Americans, as did many people living in the American West at the time. As PBS reports, native people themselves often felt that they had plenty to fear from the settlers appearing in their territories. The 1864 Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado had devastated a band of Cheyenne and increased tensions to a breaking point. A group of Sioux, Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne raided the town of Julesburg, Colorado just over a month after Sand Creek.

For Union Pacific workers, who came close to the region just a year later, the bloodshed was an ever-present worry. However, native leaders typically kept their people away from the railroad construction, though, later in the decade, some small groups attempted to derail and blockade trains, sometimes with bloody results.

Some Native people, according to the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, actually joined work crews or even provided security for the laborers. By the time the Central Pacific railroad had made it into Nevada, the company began hiring Native American workers. Charles Crocker also promised that Shoshone and Paiute tribal members would receive free passage on the completed railroad, as long as they left the workers alone.

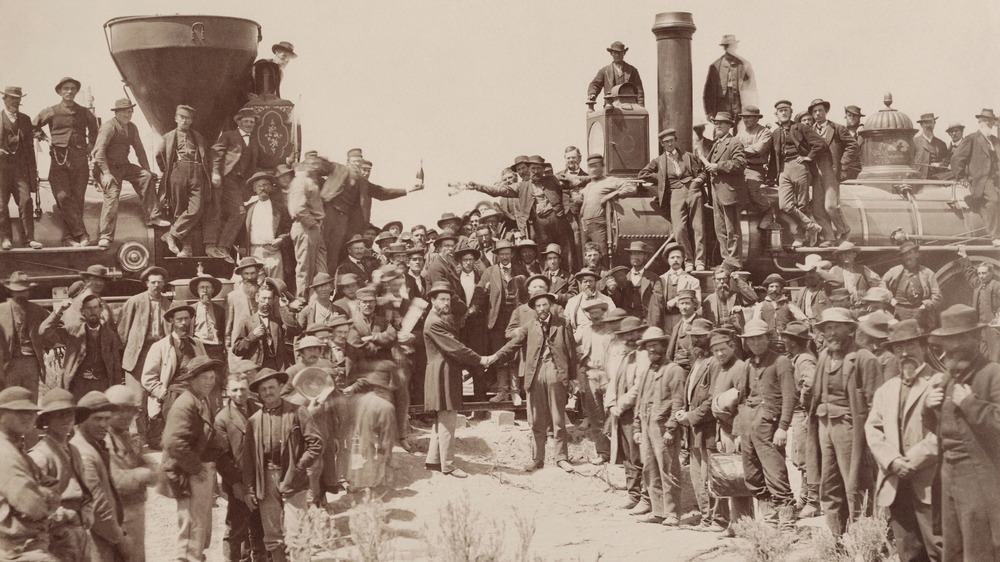

By the time the railroad was finished, many Chinese workers had been dismissed

The Central Pacific Railroad met the Union Pacific Railroad at Utah's Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869, as Ghosts of Gold Mountain reports. It was a momentous occasion, one marked by a now-iconic photograph of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific companies meeting, complete with two face-to-face locomotives and a performative handshake for the camera.

Yet, by the time dignitaries were laying the golden spike that marked the meeting of the two railroads, many Chinese workers had either been let go or were moved back west to improve the tracks. Because of the hurry to lay down the railroad in the first place, some of the line already needed repairs before it could be subjected to regular use. Because of this, as the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project points out, precious few Chinese people appear in the historic photograph.

As per the Chinese Railroad Workers project, it's possible that two people in the image — one of whom has his back turned, while another appears to be deliberately blocked by another man's hat — could be intentionally obscured Chinese workers. Other accounts, at least, make their impact clear. Chinese workers were recorded as having laid the very last rails needed to connect the two lines, thus completing the Transcontinental Railroad.