The Most Infamous Murders Of The Victorian Era

Murder is a strange thing. It's an act that to many is absolutely unthinkable, but at the same time fascinating. The idea that a human being — sometimes, a perfectly ordinary-seeming person — could take the life of another is so strange and yet so common.

And this is nothing new — people have, of course, been killing other people since they figured out how to swing a club. Fast forward to the Victorian era, and killers were still killing — they'd just gotten much more creative.

While Jack the Ripper might be the most infamous of the Victorian era's murderers, he definitely wasn't the only one. The era was downright full of dastardly men and women, and some of them committed crimes so heinous they sound like something right out of a crime novel, or Netflix special. But they're not — they're absolutely true, and even though they've been overshadowed by the infamous Whitechapel murders, they're every bit as bizarre.

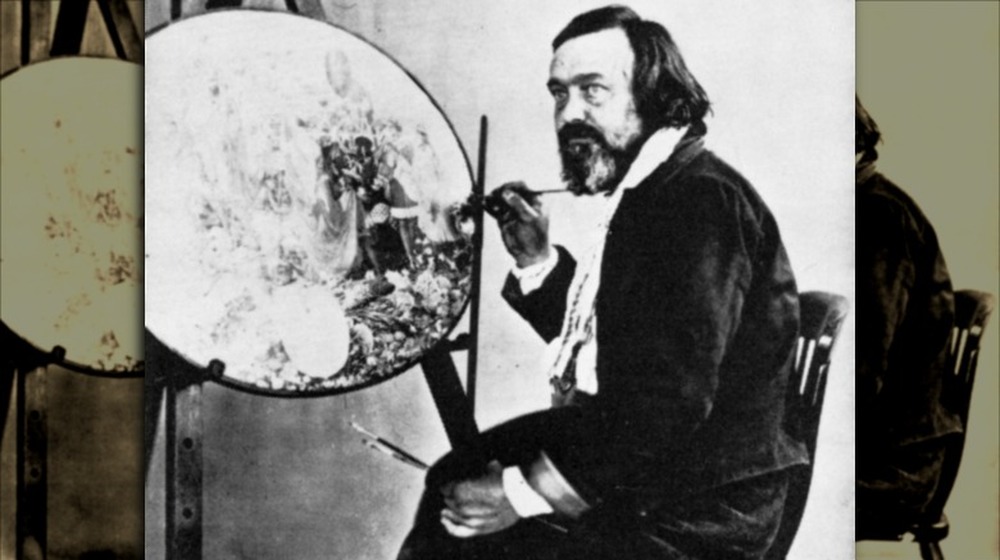

Richard Dadd: The painter who tried to kill the Devil

Richard Dadd was once known as one of the era's best artists, and he would continue to paint throughout his lifetime — eventually, from within the walls of Bedlam.

It was 1842 when he was asked to accompany a Sir Thomas Phillips on his trip around the world, and the details aren't important. What is important is that Dadd became entranced by Egypt and Cairo, and after that, things seem to change. Headstuff described him as being in a "disturbed state" by the time he headed to Italy, and there, he came to believe he was being stalked by the Devil. When in Rome, he stepped right into the figurative fire.

Backing out of his plan to kill the pope, he fled back to London, went into seclusion, and that's when his father contacted a doctor who recommended he be committed. Instead, Dadd invited his father on a trip back to their hometown, where he murdered him in what he later claimed was a sacrifice to the old gods.

Dadd was arrested on his way to Austria, when — convinced it was time for another sacrifice — he tried to kill a passenger on his train. Insisting that the spirit of Osiris was using him to kill demons, it's not entirely surprising that he was extradited to England and committed to Bethlem Royal Hospital — Bedlam. He continued to paint — his work is in museums across Europe — and died in Broadmoor.

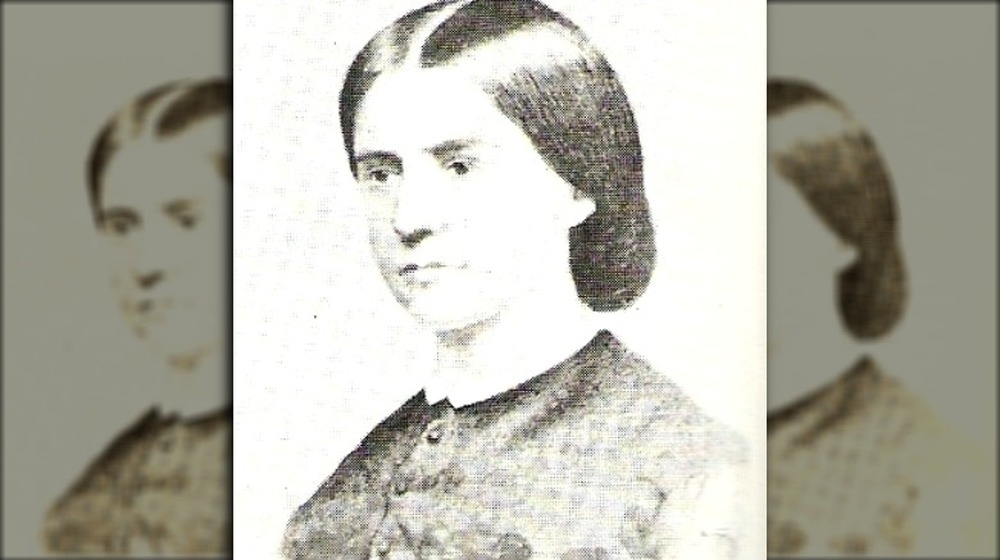

Constance Kent: The penitent killer

Francis Saville Kent was not quite four years old when his body was discovered in the outhouse of the Kent family's Road Hill House in Wiltshire. What followed was a completely botched investigation that led to the family's maid — who had been in charge of keeping an eye on little Francis — being arrested, then released.

The next person to be arrested was Constance Kent, Francis's half-sister. It was 1860, and she was ultimately released without a trial and sent first to France, then to the St. Mary's Home for Penitent Females.

And it was there, says the Wiltshire OPC Project, that she confessed to the Rev. Arthur Wagner. She had killed the boy, she said, but it had been a long time coming. Her stepmother, Mary — Francis's mother — had been her father Samuel's mistress, and Mary had made no secret of the fact that she thought Samuel's legitimate wife wasn't just unhappy, but mentally ill. Man and mistress married not long after the mysterious death of Constance's mother, and the murder of Francis was revenge for the whole sordid mess.

Constance told the reverend that she wanted to turn herself in, and he helped — while refusing to share her confession with authorities because of the privilege of the confessional. Still, she was sentenced to die and would have hanged had Queen Victoria not intervened. Instead, she served 20 years in prison before being released and moved to Australia, where she became a nurse.

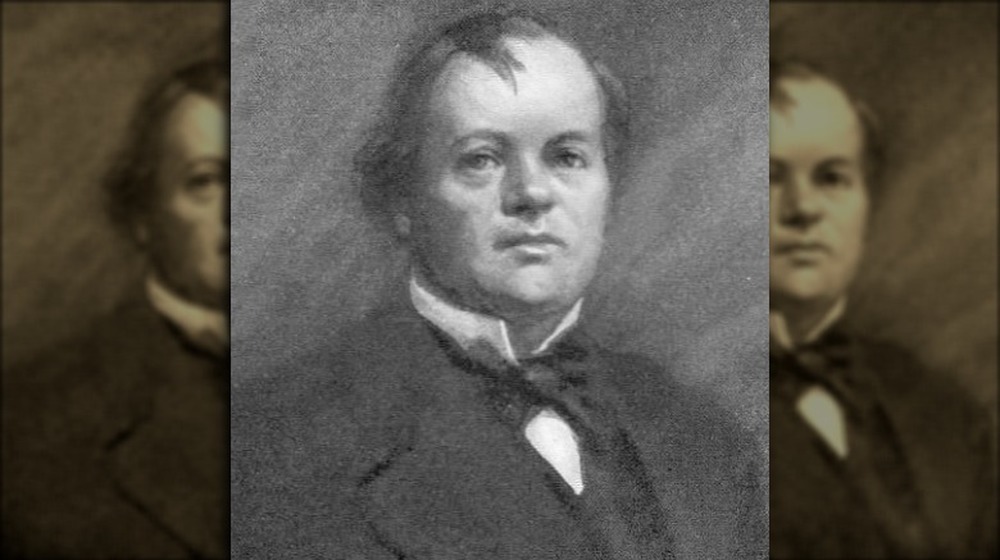

William Palmer: The Rugeley Poisoner

The British Newspaper Archive says that William Palmer was a wild child if there ever was one, and even though he had started out on a path to a successful career as a doctor, he was more interested in gambling.

It was 1855 when Palmer found himself seriously strapped for cash, and that was also when his brother — who he'd just taken an insurance policy out on — happened to die. His untimely death didn't solve any problems, though, as the insurance company was suspicious enough to withhold the payment.

Palmer had a back-up plan, which was to poison his friend and fellow ne'er do-well John Cook. The first dose didn't quite kill him and weirdly, Cook — at the same time making it clear to friends that he thought his mysterious illness was Palmer's doing — allowed Palmer to help him get back on his feet. Instead of helping, Palmer picked up some strychnine, and Cook died while screaming in agony.

Palmer attempted to bungle the autopsy by pushing the doctor and spilling his friend's stomach contents during the investigation, but The Guardian says everyone was already incredibly suspicious. That's when it was decided it was time to exhume Palmer's dead wife, and what followed was a trial that captured the interest of Victorian England. Palmer was found guilty of Cook's murder and was executed... before it could be confirmed whether or not suspicions were correct that he'd also killed his wife, mother-in-law, and four children.

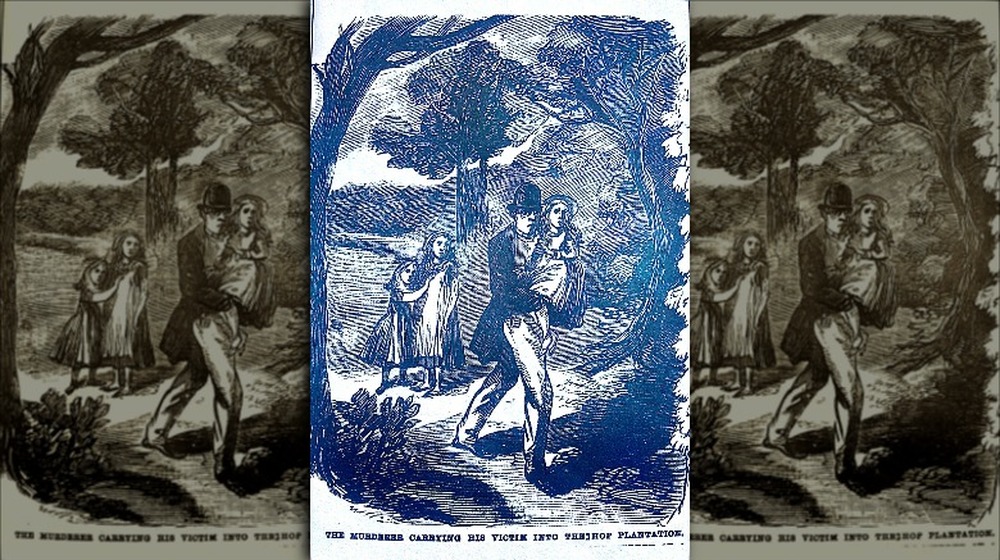

Frederick Baker: The immortal life of Sweet Fanny Adams

Little Fanny Adams was 8 years old when she, her sister, and her friend headed off to play on a terrible Saturday afternoon in 1867, getting her mother's permission then setting off for an area of Alton Hampshire called Flood Meadows.

Along the way, they ran into a local man named Frederick Baker. After offering Adams money to go with him to a nearby hop field — and giving the other girls a bribe to go away — he simply grabbed her. By the time the two other girls were able to convince some grown-ups that something was dreadfully wrong, several hours had passed.

Owlcation says that Baker was met along the road as the search for Adams began but denied any wrongdoing. The first of her body parts — her head — was found by a local hop farmer, and it wasn't long before Baker was on trial for murder. He was found guilty and hanged, but here's where poor little Adams' name gets dragged through the proverbial mud.

The story had dominated headlines for a good long while, and it was still fresh in everyone's minds at the time the British Navy introduced a new variety of rations. The running joke, says the BBC, became that the rations tasted so bad that they had to have been made from the pieces of sweet Fanny Adams that had never been recovered, and so "sweet FA" became slang for a massive disappointment.

Fred and Maria Manning: The killer couple

The murder trial of Fred and Maria Manning captured the Victorian imagination so completely that, according to Headstuff, it's tough to tell just what's true when it comes to Maria's past. Fiction writers leapt on the Swiss immigrant's largely unknown background and used some creative license to make their theories into best-selling fiction.

What is known is that when Fred and Maria met, she was already involved in an on-and-off relationship with an Irishman named Patrick O'Connor. She was a maid in the service of Lady Blantyre — and therefore sort of in the same orbit as the British royals — while she courted them both. After O'Connor made it clear that a marriage proposal wasn't coming, she accepted Fred's. Now, fast forward a bit though some shady dealing with the wrong side of the law, a few relocations, and an ongoing affair with the aforementioned Irishman.

When that Irishman didn't turn up for work one day in 1849, suspicions were raised. He was eventually found — buried under the kitchen floor of the Manning home. He'd been shot and covered in quicklime, and the Mannings had disappeared.

Maria was found in Edinburgh and Fred in Jersey, and the following trial where they pointed fingers at each other became known in the press as the Bermondsey Horror. They ended up on trial together, were both found guilty, and were executed in front of a crowd Charles Dickens described as "inexpressibly odious in their brutal mirth."

Kate Webster: A real-life Sweeney Todd?

At a glance, Kate Webster's tale is one that's as old as time — or, at least, as old as the class system. She was employed by Julia Martha Thomas in 1879, and in another old story, they clashed — a lot.

Thomas finally fired her, and HistoryAnswers says it was the last entry in her diary. Several days later Thomas had seemingly disappeared, but in her place was Webster, wearing her clothes and heading into town in a seemingly bizarre attempt to step into Thomas' life.

An investigation followed, and Webster was quickly arrested. It was finally determined that Webster had pushed her elderly employer down the stairs, then strangled her to finish the job. She then chopped the body into pieces, boiled away as much as she could, and dumped the rest in the Thames... and a foot in a garbage dump. That's true — more questionable are the claims she then sold the remaining fat to neighbors, as meat drippings.

Webster was found guilty at trial and hanged, but the story doesn't even end there. It was never clear what happened to Thomas's head, until it turned up. In 2010. In the back garden of David Attenborough. Attenborough — who lives on the same patch of land where Thomas was once murdered — was excavating the remains of an old pub when the skull was found. The Telegraph says that the age, date, and injuries are consistent with Thomas and her death.

Amelia Dyer: The baby farmer

The BBC says it's unknown just how many babies Amelia Dyer killed during her reign of terror, but historians are fairly certain that the number is in the hundreds.

Dyer was a baby farmer, and baby farmers filled a sadly crucial role in Victorian society. Unmarried women who found themselves needing to do something with an unwanted baby could pay a baby farmer to take the baby and — supposedly — find a family to adopt them. Dyer adjusted the scheme a bit. She would take the baby and the money, then simply kill the child.

And she did it for a shocking 30 years before anyone got suspicious. In 1879, she was sentenced to a few months of hard labor for neglect because of the huge numbers of death certificates she was applying for, so afterwards, she simply stopped getting them. She wasn't arrested until 1896 — when her Thames dump site was discovered, and bodies started being recovered. When she was questioned, Dyer admitted that the recovered babies were her victims — they were killed in the same way, strangled with the same white tape, and discarded. Authorities have suggested that most of her young charges were killed within hours (or at most, a few days) of coming into her care.

She was found guilty and hanged the same year, paving the way for the United Kingdom's new child welfare charities to become very influential very quickly.

Francois Benjamin Courvoisier: The celebrity murderer

Lord William Russell was a member of Parliament and was described as sort of a good-hearted but odd sort of character. It's entirely likely he may have faded into the seemingly never-ending parade of eccentric British aristocrats had his death not come in such a bloody and violent way. He had been asleep in his own bed when his throat was cut, and the trial that followed was as high-profile as high-profile gets.

His valet, Francois Benjamin Courvoisier, was put on trial with a not guilty plea, and he almost got away with it. It wasn't until well into the trial that authorities discovered Russell had caught the valet trying to steal some silver and had promised to fire him in the morning. When that motive became clear, the guilty verdict came back.

Courvoisier confessed to the murder after the verdict was handed down, and Executed Today says that's about the same time the public also found out that his attorney had known he was guilty all along. Proving these were different times, that attorney found himself publicly scorned, and it kicked off a debate as to the extent an attorney should protect a guilty client.

As for the murderer, he was hanged — after doing some autograph signing and a bit of relishing in his new-found celebrity. He was sort of immortalized after his death. Charles Dickens used his execution as some inspiration in writing Barnaby Rudge.

John Tawell: The Quaker Poisoner

It's tough to imagine a time before the world was connected in a way that made news — and arrest warrants — travel from one side of the world to another almost instantaneously. It was during the Victorian era that people were starting to get their first taste of this kind of connection. According to Headstuff, John Tawell was one of the first criminals to learn all about connections — the hard way.

Tawell was born and raised in the Society of Friends, and while Quakers have a traditionally peaceful reputation, Tawell was anything but. After getting a woman pregnant out of wedlock, it seemed like his reputation was about as bad as it could get. Still, he married her, picked himself up, and by all accounts, became a picture-perfect Quaker... until he was arrested for forgery and sentenced to 14 years transportation.

Years later, Tawell was back in England and once again, a perfect Quaker... until he hired a young woman named Sarah to care for his chronically ill wife, took her as a mistress, remarried another Sarah, had some kids with the latter, and decided to kill the former.

Tawell tried to flee, but authorities were alerted to his presence on a train to London by a telegraph sent ahead of him. He was arrested and executed.

James Blomfield Rush: The Murders at Stanfield Hall

It was a late November evening in 1848 when the remains of Isaac Jermy and his son were discovered. The murderer, it was said, had been a burly, masked man who killed both the landlord and his son before fleeing Stanfield Hall, but he didn't get far.

Police quickly arrested James Blomfield Rush, the man who had a loan coming due with the murder victims, and who the National Centre for Writing calls "the most infamous" of Norwich Castle's prisoners. He was held there while on trial, and it was a heck of a trial — starting with the fact that the sheriff sold tickets, continuing with Rush's decision to act as his own defense council, and finally, there was Rush himself. Part of the interest in the case was that he looked the part — picture not Dr. Jekyll, but Mr. Hyde.

The North Norfolk News says that it was the testimony of Rush's own mistress that secured his conviction, and predictably, that added to the drama. It got so crazy that not only did the press go nuts, but pottery figurines were even made of the couple — and the murder scene — for sale.

When he was executed, it was done in front of thousands of people who had gathered to see the end of the trial of the decade... that is, until the next grisly headline was splashed across papers nationwide.

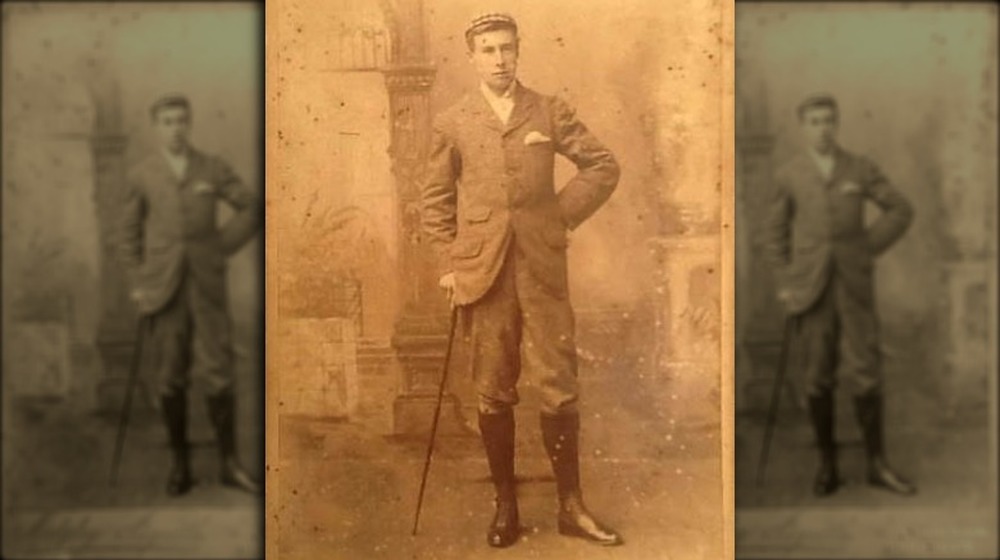

Alfred John Monson: The Ardlamont murderer?

Cecil Hambrough (pictured) was a wealthy Scottish aristocrat who headed off hunting on his 640-acre property with his tutor, Alfred John Monson, and Monson's friend, Edward Scott in 1893. Only Monson and Scott returned, and according to The Scotsman, they were busily cleaning their guns when estate staff asked what had happened to their lord. The answer was shocking — he'd accidentally shot himself in the head.

When Monson tried to cash in the insurance policies that had been conveniently taken out just six days before Hambrough's "accident," he became the prime suspect. Also, The Ardlamont Mystery (via Publishers Weekly) says Hambrough had survived a near drowning just the prior day while out boating with Monson. And finally? The gunshot wound was to the back of his head.

Experts suggest that today, it would be an open-and-shut case, especially with the sort of testimony the prosecution called to the stand. Both Dr. Joseph Bell and Dr. Henry Littlejohn, used as inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, testified to Monson's guilt.

Still, the jury came back with a verdict of "not proven," which basically means they all sort of shrugged and couldn't agree that he'd done it or didn't do it. Monson went on to set some legal precedents when he sued Madame Tussauds for putting up a waxwork figure of him armed with a gun. The case still forms the basis of defamation and libel laws, and as for Monson? Was he guilty? Sherlock Holmes thought so.

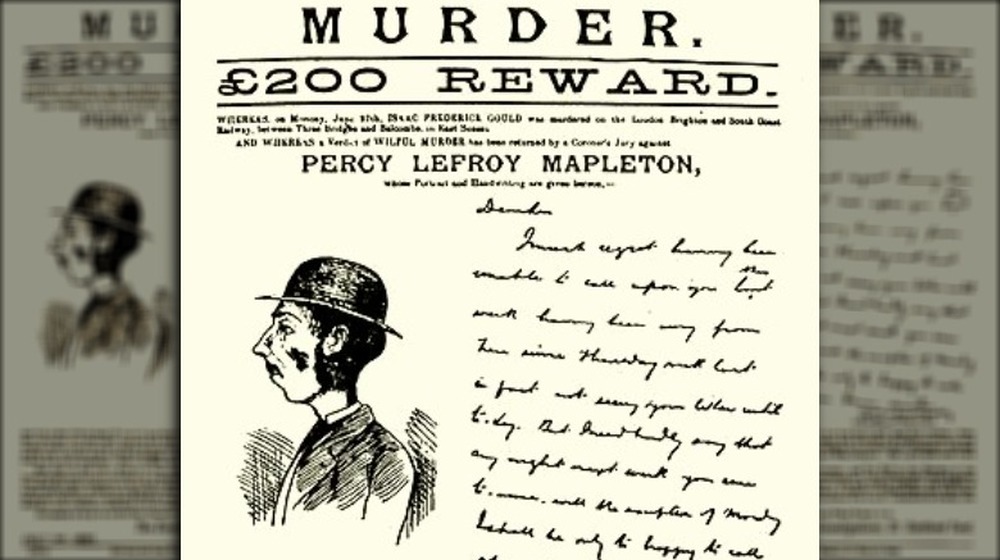

Percy Lefroy Mapleton: Have you seen this man?

Police sketches of wanted men and women are commonplace today, but surprisingly, they weren't used until the 1881 murder of a man in a train tunnel.

According to Executed Today, Percy Lefroy Mapleton had originally approached law enforcement at Brighton's Preston Park railway station with a claim that he'd been assaulted. That's why he was covered in blood, you see... and some time between Mapleton's questioning and the discovery of the body of the elderly Isaac Gold, Mapleton slipped out of the clink.

Law enforcement drew a sketch of their suspect, and for the first time, British media published a drawing of a wanted criminal. The publicity that followed was huge, and it worked. After a handful of sightings that amounted to a whole lot of nothing, a suspicious landlady and her daughter eventually led to someone raising the alarm at Scotland Yard. Mapleton was tried, convicted, and hanged.