The Crazy True Story Of The Burning Of Parliament

While it's a common cliche to imagine humankind's first major stride towards civilization being the discovery of fire (after all, there would be no hamburgers without it), fire has been as much of a danger as a boon to us. For every comfort fire brings us there's the accompanying danger of total destruction. There's no mystery why so many of history's greatest disasters involve fire — it's dangerous stuff. Once that trapped energy is unleashed in the chemical reaction that's fire, it's often difficult to contain and control it. And when fire springs up all on its own, it's even more dangerous because of lack of preparedness.

The city of London has probably suffered more from fire than most places on Earth. As The New World Encyclopedia points out, London suffered three incredibly destructive fires in 1133, 1212, and 1666, each one destroying huge portions of the city. Those fires transformed the city and had a lasting impact on the psyche of those who lived there. But a much more recent fire had just as much impact on London life — and beyond.

That fire is the 1834 fire that broke out in Westminster Palace, where the British Parliament has met for centuries. Once you dig into it, you find that everything about that epic fire is interesting. Here's the crazy true story of the Burning of Parliament.

The fire started because of changing times

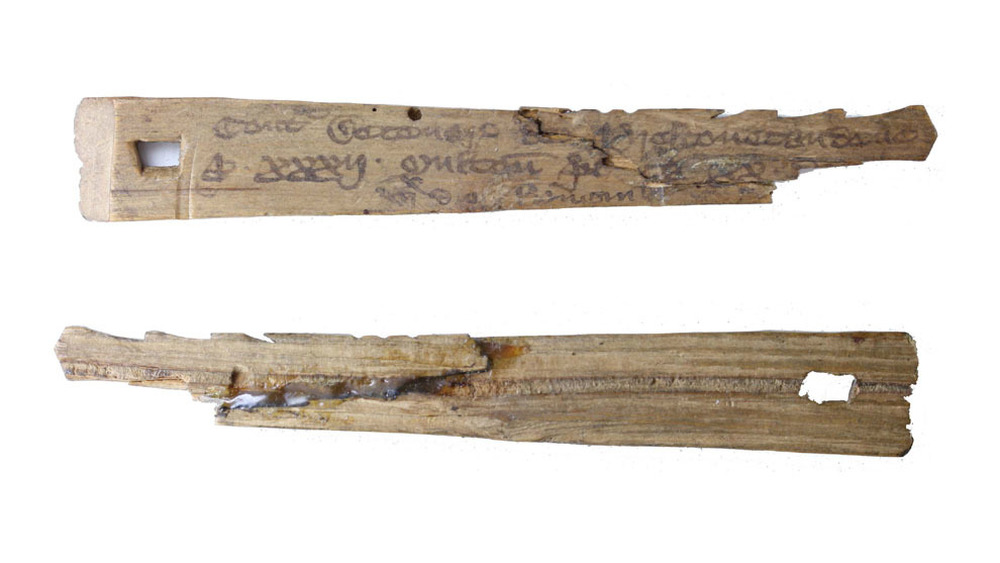

The Parliament of the United Kingdom has been meeting in Westminster Palace as far back as the late 13th century, and much of the business of running the kingdom happened there. And until the early 19th century, much of that business was conducted using what are known as tally sticks.

As The Coin Boys explains, the tally stick is a simple concept — in the days before paper was available (or at least cheap enough to be used for regular business) and when literacy wasn't universal, people still needed a way to keep records. A tally stick is simply a hunk of wood or bone that gets notched to represent a transaction. In the 12th century, King Henry I instituted a Split Tally System where thin strips of wood would be notched and marked, then split so both parties to an agreement would have a record.

As the official U.K. Parliament site notes, this system worked until 1826 when the decision was made to switch over to paper records. The tally sticks remained for another few years as they were phased out, and in 1834 an enormous number of old, obsolete tally sticks had to be disposed of. As BBC News reports, the sticks were taken into the basement of the palace and fed into the huge furnaces there — ultimately causing the fire that almost totally destroyed the palace.

Charles Dickens knew what was up

While the changeover from medieval wooden tally sticks to paper records might not seem controversial in the modern day, it caused quite a stir at the time. One of the loudest voices complaining about them was Charles Dickens.

As BBC News reports, Dickens spent some of his early career as a journalist covering Parliament and was usually on hand to observe the business being conducted. According to The Coin Boys, Dickens was a big supporter of getting rid of the old tally sticks, saying in a speech that "they never had been useful, and official routine required that they never should be."

The decision to get rid of the split tally system where pieces of wood would be notched and marked and then split into two so people could have records of a transaction was made in 1826, but the tally sticks were still used by some until 1834 when the decision was made to burn them. Too many sticks were pushed into the furnaces below the palace, stoking the fires to a dangerous point, and the palace caught fire and burned for a long time. Although there's no official record showing that Dickens was in the crowd, the official U.K. Parliament site notes it's very likely he was. And historian Caroline Shenton asserts that there's also no evidence that he wasn't there.

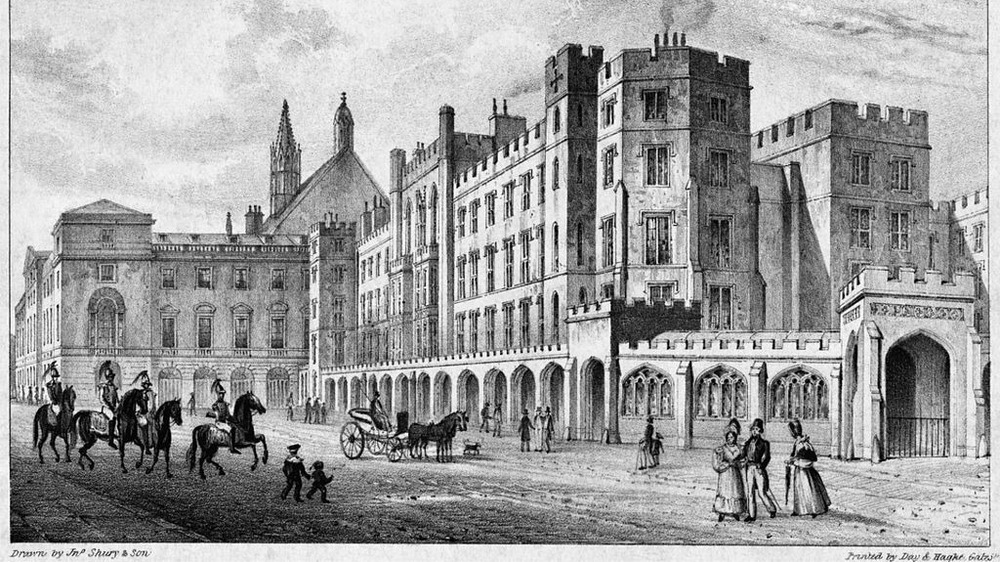

The fire destroyed the original palace

To Americans, modern-day Westminster Palace seems very old — but it's actually just about 150 years old. As the encyclopedia Britannica notes, the original palace of Westminster dated back to the reign of Edward the Confessor — the last Anglo Saxon king of England before William I the Conqueror led the Norman invasion in 1066. Described as an "incomparable structure," this palace was enlarged by William I and used as the official royal residence until the 16th century. That's when the Parliament began meeting there, using rooms that weren't really ideal to the purpose.

As reported by the official U.K. Parliament website, the fire of 1834 burned almost all of the original palace to the ground. The only part of the old palace that survived the flames was Westminster Hall, originally built in 1097 and for a time the largest hall in Europe. The rest of the ancient palace was completely destroyed after hosting the English government for centuries.

As the History of Parliament Online notes, not everyone was terribly sad about this. Members of Parliament had hoped to modernize the Palace of Westminster for years and leaped at the opportunity to actually have a space designed for the specific needs of Parliament and a world rapidly changing and only a few decades from the Industrial Revolution.

Westminster Hall was saved by the heroic efforts of citizens

The fire of 1834 that destroyed most of the old Palace of Westminster was a truly epic disaster — but it could have been much worse. Although most of the original palace was lost during a fire that burned long enough for old-timey artists to capture the event live in oil paintings and watercolors, the portion of the palace called Westminster Hall — once the largest hall in Europe and considered an incredibly important piece of British history — was saved by the efforts of the London fire brigade and ordinary citizens.

As The Telegraph reports, everyone pitched in, regardless of social status — members of Parliament (MP) and lords manned water pumps in an attempt to fight the blaze. The fire started around six in the evening, a little over an hour later local fire engines were on the scene, and at about 1:30 a.m. the London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE) managed to get a floating fire engine close to the flames. As the History of Parliament Online notes, the LFEE was a private fire fighting company led by Superintendent James Braidwood, considered to be a leader in the movement towards modern fire fighting strategies.

Once this disparate group realized most of the palace was a lost cause, they concentrated all of their efforts on saving Westminster Hall — and succeeded. The fire fighters were all paid in something better than money — beer.

The fire burned so long it was painted — live

As you may be aware, 1834 was long before cameras were a thing. As a result, our view of the past is often distorted. Portraits of historical figures were often tweaked to make them more attractive, and paintings of historical events were often composed and completed years, decades, or even centuries after they occurred.

But the 1834 fire was different. The fire was incredibly intense and burned all night long. According to the official U.K. Parliament website, several artists joined the crowds that thronged the streets to view the fire — and recorded the moment, live, in sketches, watercolors, and oil paintings in a remarkably rare example of history being captured in real time prior to the advent of electronic gadgets.

As The Independent reports, one of those artists was Joseph Mallord William Turner, who produced two paintings and a series of watercolors supposedly depicting the burning of Parliament from a view on the river. However, it's recently been determined that the watercolors actually depict a completely different fire in London that occurred seven years later. Turner's two paintings, however, definitely show Westminster Palace as it burned to the ground.

There's disagreement on who to blame for the Westminster fire

When the decision was made to dispose of the ancient tally sticks once used to keep track of accounts and other parliamentary business, two men were hired to handle burning the huge number of tallys that were now just so much kindling — Patrick Furlong and Joshua Cross. As noted by the BBC, no one disputes that Cross and Furlong overloaded the furnaces, shoving too many of the sticks into each, which overheated the fire and melted the copper lining of the chimney flues. But there is some disagreement as to who to blame the most.

As reported by The Independent, Cross had been placed in charge by Richard Woebly, clerk to John Phipps, assistant surveyor for London in the Office of Woods and Forests. Woebly took care to warn Cross not to overload the furnaces — instructions Cross clearly ignored, possibly in his desire to get the work over with quickly.

According to historian Caroline Shenton, Furlong was known as a good member of the community who had worked for Westminster for years and likely hadn't been told the warning about overloading the furnaces. Cross, on the other hand, was a convicted criminal with a sketchy reputation who probably shouldn't have been placed in a position of authority.

There were a lot of conspiracy theories

For something that happened nearly 200 years ago in a time before film and audio technologies, there's actually very little mystery about what caused the fire that destroyed Parliament in 1834 — obsolete wooden tally sticks were burned in the furnaces below the palace, lazy or incompetent laborers pushed too many of the sticks into the fire, and things got out of control. Case closed.

As historian Caroline Shenton writes, however, plenty of conspiracy theories sprang up almost immediately to ascribe the fire to nefarious forces. The prime minister at the time, Lord Melbourne, received an anonymous letter claiming that "an operative" had been paid to start the fire and to douse the walls of the palace with turpentine to ensure it burned out of control. Others blamed plumbers who had been working in The House of Lords or the coffee house located inside the building. In fact, there were so many conspiracy theories floating around, an official inquiry had to be set up to investigate them — though many people saw the inquiry as a superficial response to the public's frenzied interest.

In the end, the committee charged with the investigation concluded that the obvious solution was the correct one — the men assigned to burn the tally sticks had done a terrible job of it.

The Westminster fire was truly epic

You might read that the old Palace of Westminster was destroyed in a fire and not think much of it, but this was no ordinary fire. As noted by the official website of the U.K. Parliament, it caused the most damage to the city of London of any single event between the Great Fire of 1666 and the German Blitz in World War II. When it broke out, a "huge fireball" exploded into the night sky, attracting thousands of onlookers on land and on the river.

Once the fire got going, it burned exceedingly well — according to The Guardian, the fire could be seen by King William IV and Queen Adelaide at the palace of Windsor, 20 miles away. And in an age before modern fire fighting technology, it burned for a very long time. The fire started around 6 p.m. and wasn't extinguished until the next morning.

Aside from the damage the fire did, totally destroying the ancient building that had hosted Parliament since the 1500s, the fire attracted a record-setting crowd. Several dozen artists set up their easels in the streets and on boats to capture the scene, hundreds of people suffered crush-related injuries as people jostled for a better view, and it's said you could walk across the Thames River because so many boats had crowded onto its surface.

The fire destroyed irreplaceable government records

The Palace of Westminster is where the Parliament has assembled since the 1500s to do the business of government. Three hundred years of government business means a lot of records — laws, transcripts, votes, speeches, and the accumulated cruft of bureaucracy.

And as the Library of Congress notes, almost all of it was destroyed in the fire of 1834, making it known as "one of the greatest archival disasters the United Kingdom has ever known." What makes this loss ironic is the fact that the fire was started because many of those ancient records had been kept on what are known as "tally sticks," old pieces of wood dating to a time before paper was cheap and plentiful. When the decision was finally made to modernize and shift record-keeping to paper, those sticks were burned — sparking the fire that destroyed all the records.

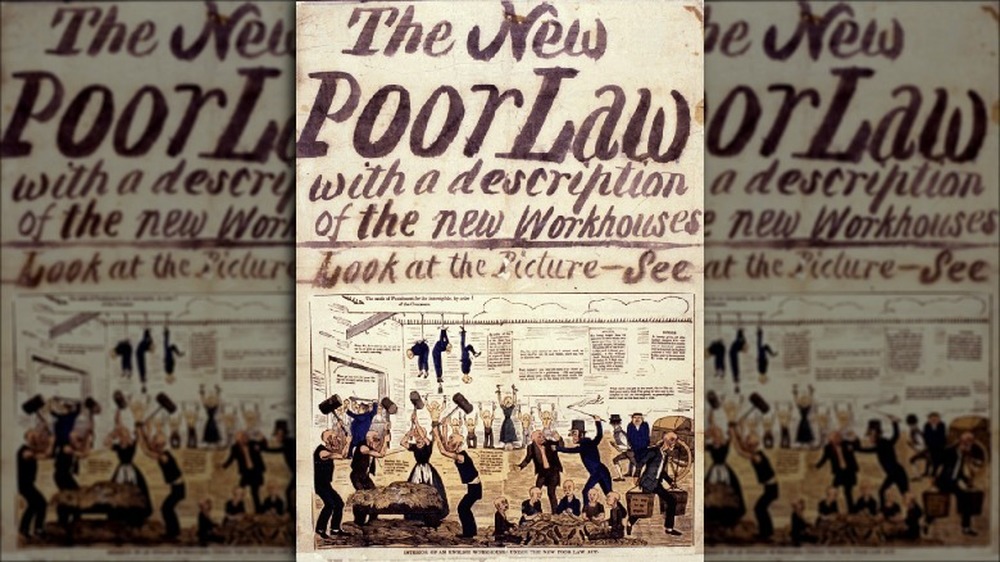

Not everyone was sad about this. As The Guardian notes, just a few months earlier Parliament had passed the notorious Poor Law, which guaranteed the poor support and limited education but required them to work several hours a day in exchange. Many people hated the law, fearing it amounted to perpetual indentured servitude — and when the written copy of it burned up with everything else, an ecstatic rumor circulated that this meant the law was no longer in force.

The Westminster fire prompted an architectural competition

The old Palace of Westminster that was destroyed in the fire of 1834 was an ancient, medieval structure dating back to the 11th century and was heavily altered over the years. New additions, extensive renovations, and other changes had created a massive and confusing complex that was, ironically, incredibly crowded. As The Guardian notes, despite the immense size of the palace, the rooms where the House of Commons and the House of Lords actually met were tiny, and yet nearly 700 people gathered in them for hours at a time — rumor has it some MPs voted against their own interests just to hang onto a good spot.

So there had been talk of moving Parliament or finding a new, more modern space for the government long before the fire — but after the fire, the government saw an opportunity. As ArchDaily reports, a competition was organized to choose an architect to design a new palace, one that was both better organized for Parliament's needs and which represented Great Britain as a world power. Nearly 100 world-class architects submitted designs, and Charles Barry was selected as the winner with a relatively economical design that favored utility over flourish.

Barry won the competition, but he lost the war. He faced delays, endless requests for redesigns (the House of Commons hated their new space when they began using it in 1850, and Barry had to rework it), and died in 1860 ten full years before the project was finished.

The new palace gave the world Big Ben

Big Ben is one of the most recognizable landmarks in the world. Despite its fame and prominence, most people get two vital facts about it absolutely wrong. First, as History tells us, "Big Ben" doesn't refer to the tower or the clock — it refers to the bell inside that chimes the hours. Over the years the name has come to unofficially apply to the whole tower, but the official name of the tower is the Elizabeth Tower. It was named after Queen Elizabeth II in 2012, says Britannica. Originally it was just called the Clock Tower.

Second, it's not as old as you might think. While many assume the tower has to be centuries old and date back to the Middle Ages, it was part of the new Westminster Palace complex built in the wake of the great fire of 1834. Part of the plan for the new palace came to include a clock tower that would be incredibly accurate, which most people thought impossible at the time. The royal astronomer, Sir George Airy, helped design the clock to prove them wrong.

As History Daily tells us, the foundation stone for the tower was laid in 1843, and construction lasted until 1858, when the enormous bell was hoisted to the top of the tower. Far from being an ancient relic, Big Ben and the tower it sits in are just over 230 years old.

People worry it could happen again

After the Palace of Westminster burned down in 1834, a whole new palace was built on the same site. But it's been a minute since then, and the buildings haven't had any serious renovation since. As BBC Travel notes, the whole complex is beset by problems. The roofs leak really badly, the whole place is infested with rats, the sewage system hasn't been upgraded since 1888, and the place is absolutely loaded with asbestos.

Worse, the place was never designed for modern technology, so gas and electrical systems have been installed wherever they might fit. This often means they sit right next to or on top of leaking water systems, and as everyone knows water and electricity don't mix well.

In fact, just a few years ago The Guardian revealed that the only reason the palace is considered legal to use in the modern day is because it employs 24-hour fire patrols. In other words, all day every day a team walks around the palace making sure it isn't about to burn down again. That's because not only is the aging palace at real risk of catching fire, the fire alarm system is woefully inadequate, so if a fire were to break out there wouldn't be sufficient warning for fire fighters.

As inews reports, repairs are planned — but will be costly, take years, and might require Parliament to vacate the building for five to six years.