The Untold Truth Of Hank Aaron

The baseball world had to say goodbye to many diamond heroes in 2020. Hall of Famers such as Joe Morgan, Tom Seaver, Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, and Whitey Ford all passed away just between the months of August and October, and 2021 hasn't fared better for the sport. In the first month of the year, Hall of Fame manager Tommy Lasorda and pitcher Don Sutton both passed away. On January 22, the country had to say farewell to an icon known both on and off the baseball field, Hank Aaron.

As a player, Aaron's career places him as one of the greatest in the century-plus history of the sport. Both Bleacher Report and ESPN ranked him the fifth-greatest player in the sport's history, which still might be too low for him. Fellow Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle (who was ranked No. 13 and No. 9 on the lists) said this about Aaron in Baseball Digest in 1970: "As far as I'm concerned, [Hank] Aaron is the best ball player of my era. He is to baseball of the last fifteen years what Joe DiMaggio was before him. He's never received the credit he's due."

By 1970, Aaron still had six more years left in his career and would change the game and nation forever in those years. Aaron, in the face of racism, challenged an American hero and emerged scarred, but victorious. Here is the untold truth of "Hammerin' Hank Aaron."

From Mobile to the Majors

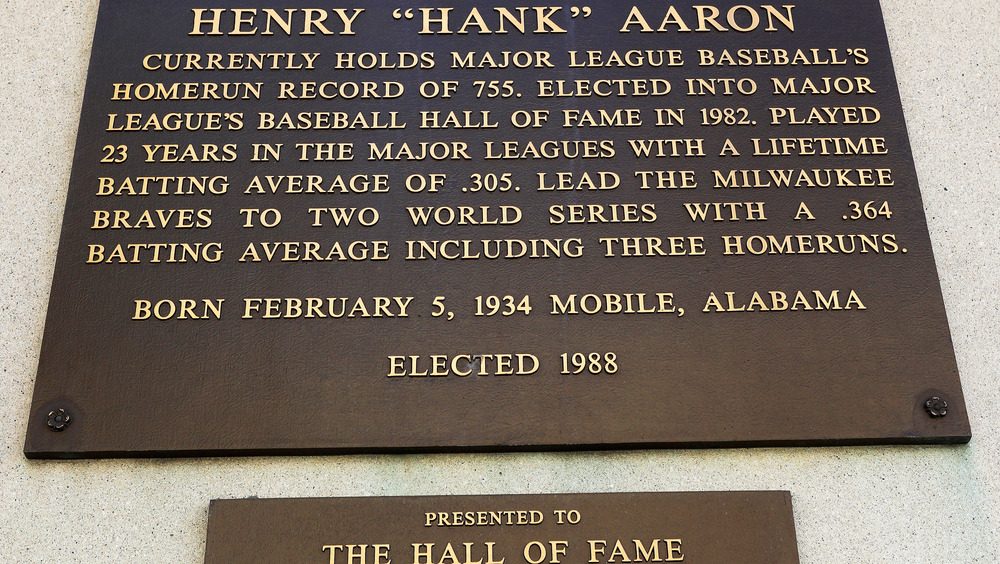

Henry Louis Aaron was born February 5, 1934, to Estella and Herbert Aaron in Mobile, Alabama. He was the third child of eight. According to Biography, Aaron developed a love of baseball and football as a young child, giving more attention to sports than school. The Toledo Blade interviewed his father in 1974, and the proud Herbert discussed his son's love of baseball. Like many Black children of the era, Henry idolized Brooklyn Dodgers star Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball's color barrier when Aaron was 13 years old. Aaron told his father he would make the pros before Robinson retired.

At 18 years old, Aaron dropped out of high school after being signed by the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro American League. According to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Aaron spent one season with the Clowns, making $200 a month and batting a league-best .467. Next, his contract was sold to the Boston Braves for $10,000, according to ESPN's SportsCentury. The Braves assigned Aaron to the Eau Claire Bears. In 1953, he became one of the first players to integrate the South Atlantic league. Playing in the South, Aaron faced a barrage of racist taunts from fans and players. In the first integrated game in Atlanta, Aaron hit a home run in the first inning, and fans attempted to hit Aaron with rocks, leading to the game being stopped. Still, Aaron won the Most Valuable Player award in his only year in the minors. By 1954, Aaron would be a Major League player.

Silent but deadly

Before making the majors in 1954, according to author Ralph Wiley, Aaron hit a ball so hard that Boston Red Sox star outfielder Ted Williams ran out to the opposing clubhouse to see who had hit the ball. Despite his immense talent, Aaron's bat was the only thing that talked.

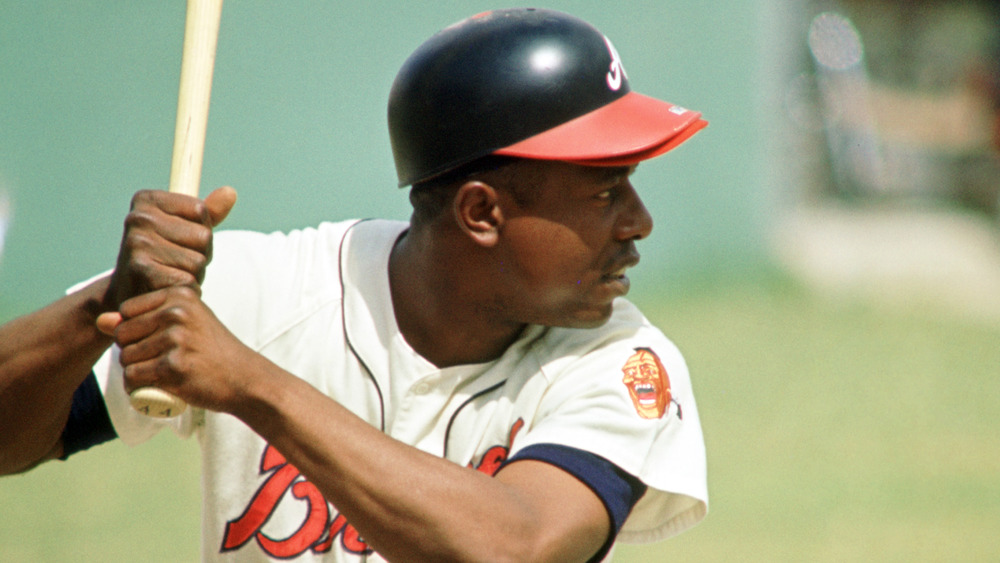

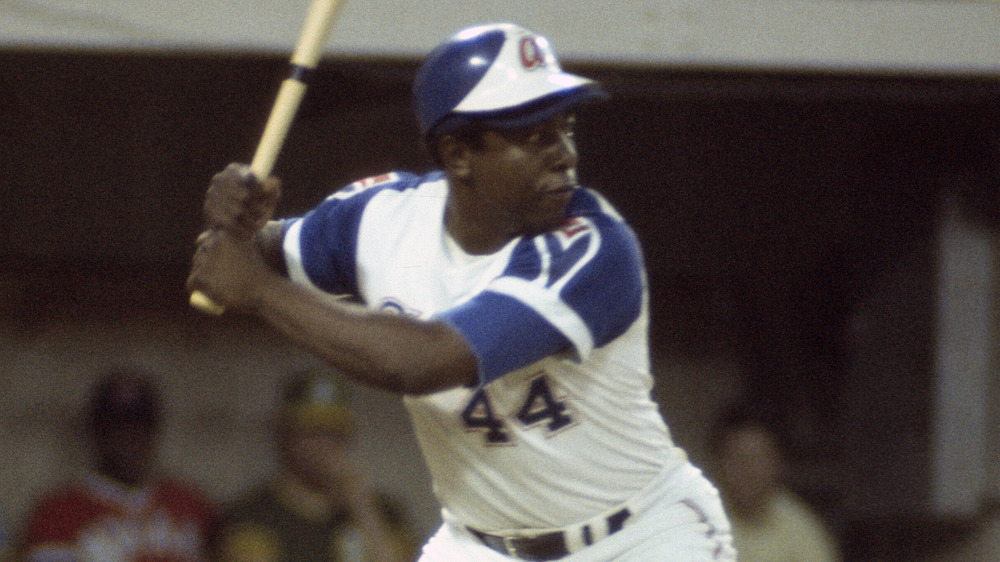

Throughout his career, Aaron did not play in a major media market like Mickey Mantle, and his playing style wasn't known for being "flashy" like Willie Mays. Aaron himself said, "I didn't do things with a flair by no stretch of the imagination." His quiet demeanor often led fans to overlook him throughout his career. According to the Encyclopedia of World Biography, despite being consistently at or near the top of the home run list year after year, it wasn't until 1970 that people began to notice how close he was to the all-time record. The few times he did appear on the biggest stages, Aaron proved he had no equal.

The Home Run Derby today is an annual event held during All-Star week. In 1960, it was a television program that pitted two hitters against each other. Against the best hitters of his era, Aaron won a record six times and took home the most cash, according to The Postgame. On the field, in his only World Series victory in 1957, Aaron led Milwaukee in every major offensive category against the dynastic New York Yankees. Aaron was overlooked for the series MVP honor, which went instead to pitcher Lew Burdette.

What Hank Aaron's contemporaries said about him

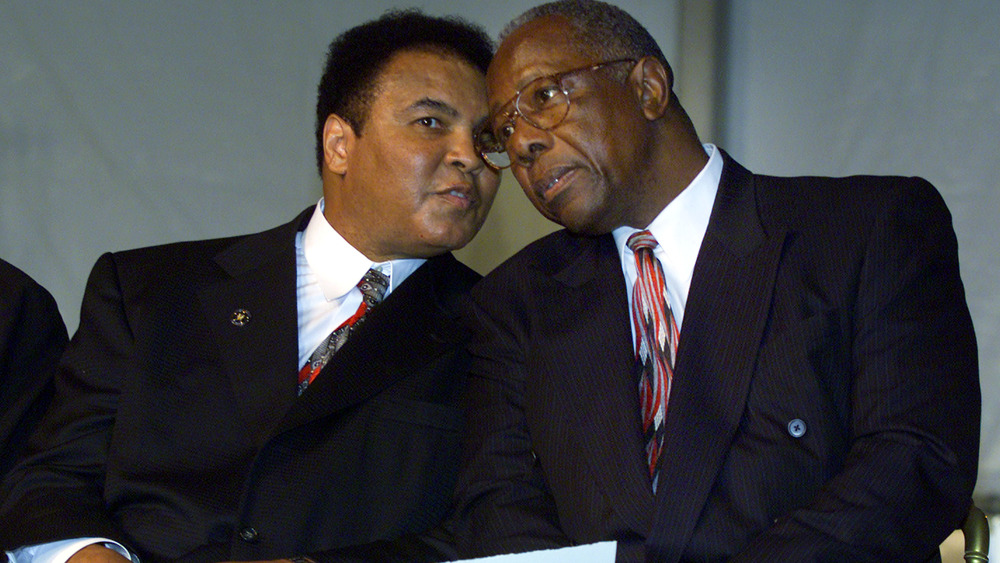

Yankees superstar Mickey Mantle looked at Hank Aaron as the greatest player of his generation. Mantle certainly isn't a minority in this assessment, either, as Aaron's contemporaries were left in awe from watching him. They had plenty of compliments for him as they were interviewed following Aaron's selection for Baseball's All-Century Team.

Aaron, known for his steady consistency throughout his 23-year career, left some painful memories for pitchers who had to face him. Jack Mann of Newsday remembered a nickname Dodgers Hall of Fame pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale gave to Aaron: "Bad Henry." Koufax had this to say: "For me, he was the toughest out. Everybody else, I had a plan. For Henry, I just never figured out what I was going to do."

Pitchers employed different strategies to deal with "Bad Henry." The "brushback pitch," or a pitch thrown intentionally inside to intimidate a batter, was used often against Aaron. Fellow Hall of Fame pitcher Gaylord Perry recalled about the strategy, "When you knocked Aaron down, you weren't doing yourself any good because he got tougher."

Aaron was as feared as he was respected. Aaron's father recalled a story of his son silencing the racist crowd with his bat: "I heard fans yell, 'Hit that ni**er. Hit that ni**er.' Henry hit the ball up against the clock. The next time he came up, they said 'Walk him, walk him."

Chasing the Babe came with a price

When one thinks of Hank Aaron, the first thing that comes to mind is breaking the all-time home run record held by Babe Ruth. Ruth's career record of 714 was so great that it was believed to be unbreakable. However, as the 1970s began and Aaron's consistent performance continued, many fans and outsiders in the sport made sure Aaron knew how they felt about a Black man overtaking Babe Ruth.

Aaron received thousands of pieces of hate mail, threatening him and his family if he kept on pace to break the home run record. On the 20th anniversary of breaking the record, Aaron spoke candidly about the experience to The New York Times. "My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp. [...] I was getting threatening letters every single day. All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won't go away. They carved a piece of my heart away," Aaron recalled.

Terence Moore, a longtime sports journalist based in Atlanta, had this to say to WXIA-TV about the hate Aaron faced during his pursuit of the all-time home run record: "It's a lot worse than we even know, trust me. Hank doesn't like to talk about it. [...] If people truly knew the story of what he endured and for him to go through it with dignity and still be productive [...] it's just astounding."

Hank Aaron vs. the commissioner

After a long winter concluded, the 1974 season was set to begin with Aaron sitting at 713 career home runs. One to tie, two to win. However, during this time, the commissioner of the MLB, Bowie Kuhn, and Aaron began to butt heads. According to the New York Post, Atlanta opened the season with a three-game road trip in Cincinnati, and Aaron and the Braves wanted the record to be broken at home in Atlanta. However, Commissioner Kuhn ordered Aaron to play in at least two of the road games, so Aaron played the first and third games.

Aaron began the season by tying the record with a home run on April 4, but he was fuming behind the scenes. ESPN's SportsCentury states that Aaron had asked that there be a moment of silence in honor of the six-year anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. His request was denied, with time constraints being blamed. Aaron did not homer again in the third road game, which meant he returned to Atlanta only one home run away from the record. In front of a celebrity-packed crowd and with millions watching on television, Aaron broke Babe's record. Missing from the celebration was Commissioner Kuhn, the commissioner citing scheduling conflicts for his absence.

This, coupled with what he felt was unfair treatment of Black players, led Aaron to resent Bowie Kuhn. According to This Day in Baseball, in 1980, Aaron refused an award from his old rival in celebration of his record-breaking home run, criticizing the MLB's treatment of retired Black players.

April 8, 1974

In 1961, Yankees slugger Roger Maris broke Babe Ruth's single-season home run record by hitting 61 in a season. During the season, according to Newsday, the pressure led Maris to suffer from anxiety and hair loss. So imagine years instead of months chasing Ruth? In an interview looking back on the home run chase, Aaron called 1972 and '73 as "two of the toughest years" he had as a baseball player, saying that the excessive media attention limited his mobility.

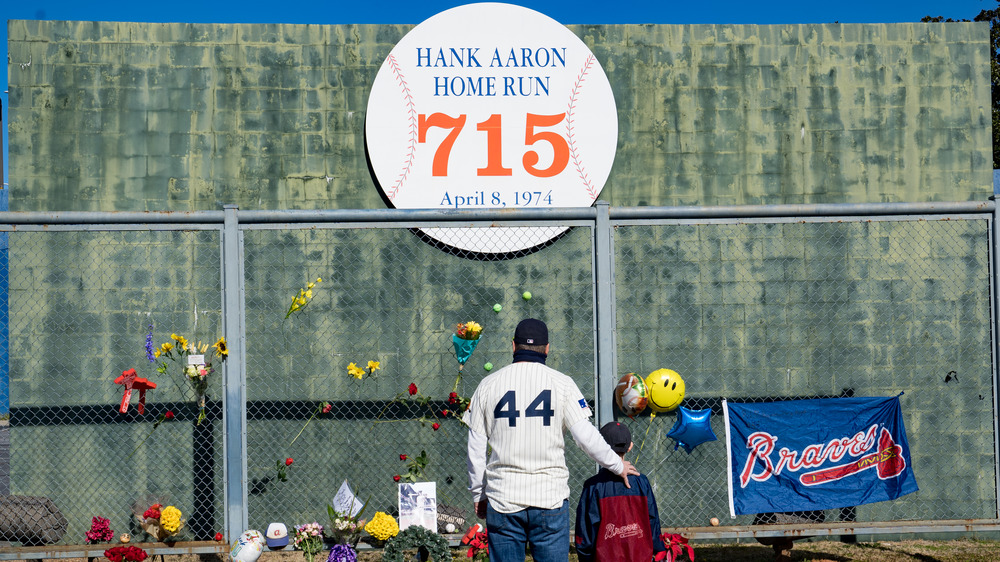

Then April 8, 1974 came. According to History, the attendance that night was 53,775 people, the highest in the park's history. Against the Los Angeles Dodgers, Aaron stepped to the plate in the fourth inning. His teammate, Dusty Baker, who was batting after Aaron, recalled Aaron saying, "I'm tired of this, I'm gonna get it over with."

Being the veteran, savvy player he was, the sequence went as predicted, and Aaron smacked the ball into the Atlanta Braves' bullpen for No. 715. As he was rounding second base and the crowd was exploding in a frenzy, two white fans ran onto the field. Aaron's wife, Billye, remembered being terrified for a moment at the sight of the two men following her husband. However, the fans simply patted Aaron on the back and congratulated him.

Hank Aaron wasn't just the home run king

Despite Hank Aaron's home run record being his legacy in baseball, only surpassed 33 years later by Barry Bonds (with great controversy, as Bonds admitted to using performance-enhancing drugs), other records remain untouched by other players. According to Baseball-Reference, Aaron still holds the record for career runs batted in, or RBIs, (2,297) and total bases (6,856).

Aside from that, Aaron was an elite defensive player. After spending his pre-professional career as an infielder, Aaron found a permanent spot in the outfield, which worked out, as Aaron's infield abilities were not at a professional level. After a preseason game prior to being promoted, Dodgers outfield Duke Snider recalled about the minor leaguer Aaron, "I don't think much of him as a second baseman, but the way he swings a bat, they're going to find a place to play him."

Aaron played 2,174 of his over 3,000 games as a right fielder, according to Baseball Almanac, and won three Gold Glove awards, given to the best defensive player at a specific position. Unlike many other power hitters, Aaron's strikeouts remained very low, averaging only 68 strikeouts per season. By comparison, Barry Bonds and Babe Ruth averaged 83 and 86 per season. The late Tom Seaver said it best when describing "Hammerin' Hank": "The thing that people should know about Henry is [...] how good an all-around player he was. That's one of the most overlooked aspects of his career."

Hank Aaron's family

With seven siblings and six children, Hank Aaron comes from a large family. Unsurprisingly, Aaron wasn't the only member of his family to don a major-league uniform. His younger brother, Tommie Aaron, played seven seasons in the MLB, all for teams with his older brother. According to the Baseball Wiki, Tommie was less known for his bat and more known as a defensive specialist at first base.

Before entering the pros, 19-year-old Hank Aaron married Barbara Lucas in 1953. The couple had five children: Gary, Lary, Dorinda, Gaile, and Hank Jr., as told by HITC. The couple divorced after 18 years of marriage in 1971. Three years later, Aaron married Billye Jewel Suber and adopted a daughter, Ceci, CNN reports.

According to Nicki Swift, Billye shared in her husband's crusade for racial equality. Born in 1936 in Arlington County, Texas, Billye valued education throughout her life. She earned a bachelor's degree at Texas College and her master's at Atlanta University. For 12 years, Billye worked as a high school and college teacher. At the same time, she became the first Black woman to host a regularly scheduled talk show in the Southeast when she was picked to co-host Today in Georgia. She interviewed celebrities, politicians, and activists on the program before earning her own talk show in 1975. She has also been on the boards of Texas College and Morehouse College and fundraised for the United Negro College Fund.

Hank Aaron's place in the Civil Rights Movement

Beyond the home run chase, Hank Aaron was on the front lines of civil rights during and after his career. According to SportsCentury, Aaron was one of the baseball players in the early 1960s who pushed to desegregate Spring Training facilities in Florida. In 1966, the Milwaukee Braves became the first professional league to move to the Southeast, becoming the Atlanta Braves, right in the heart of the Civil Rights Movement.

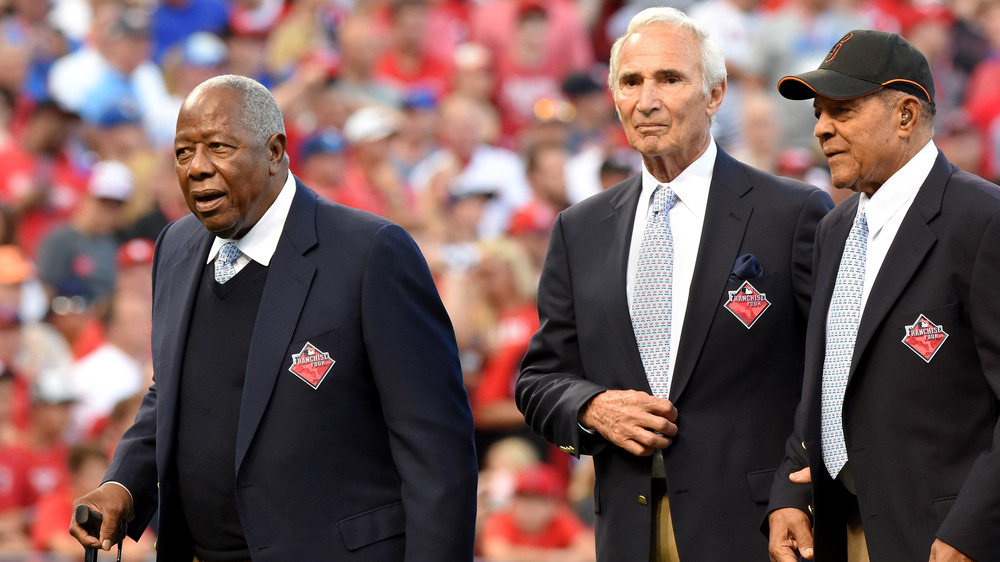

Aaron entered the league only two years before Jackie Robinson's retirement. After idolizing Robinson as a teen, Aaron told Dan Patrick in an interview that he would talk to Robinson during and after games, learning from his hero. According to The Undefeated, players like Aaron, Willie Mays, and Willie Stargell guided young African-American athletes on and off the field, like how Robinson did for him.

Still, the home run chase and the racism he endured during that time remains the greatest testament to Aaron's strength. My Black History reports that after the 1973 season ended with Aaron one home run shy of tying the record, he told reporters he feared he would not live to see the next season. Lewis Grizzard, the sports editor of the Atlanta Journal, had privately written an obituary for Aaron on the all-too-real chance he would be murdered before breaking Ruth's record. Aaron kept and occasionally read many racist letters he received, saying of them, "They remind me not to be surprised or hurt. They remind me what people are really like."

Hank Aaron's post-MLB career and honors

For a player and man as great as Hank Aaron, it would be an injustice if his retirement in 1976 was the end of his time in the spotlight. With very little debate, Aaron was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 1982. Upon retirement, according to Bleacher Report, Aaron was hired by the Atlanta Braves as the director of player development. He was the first African American to hold a senior-level management position in baseball, as reported by CBS Sports. Aaron remained connected with the Braves organization throughout the rest of his life.

According to ESPN, in 1999, the MLB announced that the best hitter in both the American and National League would receive the Hank Aaron Award. At the 2015 All-Star Game, Aaron, along with catcher Johnny Bench, outfielder Willie Mays, and pitcher Sandy Koufax (the man who referred to Aaron as "Bad Henry"), were honored as the four greatest living ball players. In 2002, President George W. Bush awarded Aaron with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor one can give a civilian. In 2015, the National Portrait Gallery honored Aaron by making him one of their first five individuals selected for their gala.

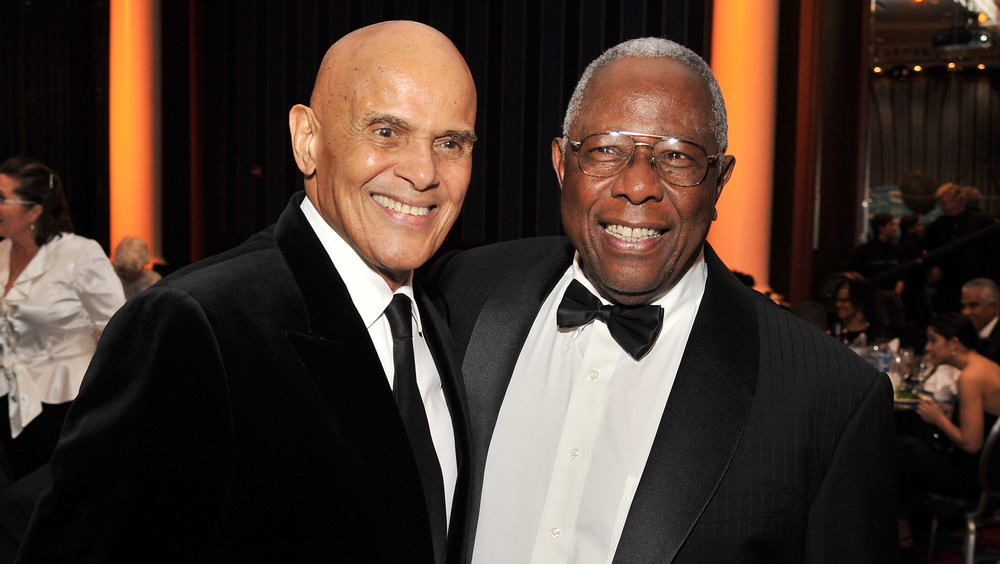

After years of being left out of honors and celebrations because of his quiet posture and the color of his skin, the twilight of Henry Aaron's life saw him properly celebrated for his accomplishment.

Hank Aaron's final year

Despite his advancing age, Aaron remained connected to both baseball and the African American community. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Aaron won the Musial Lifetime Achievement Award for Sportsmanship in 2020 and had meant to accept it and speak in St. Louis. The ceremony for the award, named after Aaron's late longtime friend and fellow Hall of Famer Stan Musial, ended up being held virtually, with Aaron accepting the honor.

In an interview with Today in February 2020, Aaron said it was "hard to digest" that his record was broken by Barry Bonds. Bonds' name had been connected to steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs, and he admitted to unknowingly using them for a period of time. Still, he acknowledged Bonds, recognizing him as the true all-time home run leader.

On Friday, January 22, 2021, Henry Aaron passed away at the age of 86. Less than three weeks before his death, Aaron was vaccinated for COVID-19 and pleaded for others in the Black community to get vaccinated as well. His death led many to speculate it was linked to the vaccine, though the Fulton County Medical Examiner's office said he passed away from natural causes.

Henry Aaron's childhood involved episodes of hiding under his bed as KKK members marched through his neighborhood. When he passed eight decades later, Georgia governor Brian Kemp ordered flags flown at half-staff, according to ESPN, and citizens and celebrities alike all honored the legend in their own way. Hank Aaron transcended his sport to become an American icon.