The Truth Behind The Great Stink Of London

When it comes to the most disgusting periods in history, the summer of 1858 is a serious contender. That's when London was enveloped by something called "the Great Stink," and that pretty much sums up what was going on in this seemingly metropolitan capital of the world.

Everyone loves a good, Victorian-era period drama, but here's some food for thought — one of the things that the big screen just can't capture is the smell — and it wasn't just bad, it was mind-numbingly bad. All those fancy people in their Victorian finery were walking through streets and homes that might as well have had some cartoon-style stink lines drawn all over them.

The Guardian says that it was a few extraordinarily hot summer months that finally made it unbearable and finally got people moving toward change. And oddly enough, London today wouldn't be the city it is had the smell not gotten so bad that they decided to change the landscape of much of the city in order to fix it. So let's talk about London's hygiene problem and the monumental project that needed to take effect to make it a bearable — and safer — place to live.

Victorian-era London had been smelling really bad for a long time

The people who flooded into 19th century London came with a lot of smells — and most of them weren't pleasant. Lee Jackson is the author of Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth and told NPR that keeping the city clean was "an immense and impossible challenge."

For starters, the city was filled with horses. How many? By the late 19th century, the 300,000-odd horses in London were producing around 1,000 tons of poop each and every day. And here's the thing — that wasn't even the worst stuff on London's streets.

Human excrement is approximately a million times worse than horse poop, and London — particularly, the Thames — was full of it. Jackson says (via Yale Books) that raw sewage was the city's biggest problem, but it wasn't the only one. In addition to that, there was the sulphuric-smelling fog and the soot and smoke that filled the air. Then, there were the consequences of human activity — streets were filled with rotten food, spilled beer, overflowing garbage cans, and something called dust, which was ash and soot from fires.

Charles Dickens wrote extensively on the sights and smells of Victorian London and noted that the streets were a press of unwashed bodies wearing dirty clothes. And, don't forget that herds of cattle were often driven through the streets on their way to the city's slaughterhouses and markets. The smell would have been unbearable.

How on earth did it get so bad?

To understand the root of the problem, it's necessary to take a look at London's growth. According to the Old Bailey, London was home to around half a million people in the late 17th century. During the Victorian era, things started getting out of control, and by 1860, there were 3.1 million people calling the city home. Simply put, the city wasn't built to hold that many people.

Lee Jackson, author of Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth, told NPR that one of the major problems was the city's cesspools. Homes that were built in the center of the city came with a cesspool — kind of like a Victorian-era septic tank — that was basically a pit about 6-feet deep. Waste went in, liquids seeped out through the porous sides, and the so-called night soil men cleared out the solids (then sold it as fertilizer).

It might not have been the most environmentally friendly solution, but it worked... until indoor plumbing came along. Once people started putting flushing toilets and water closets in their homes, the water being pushed through the system was too much for the old construction to handle. Everything — excrement included — started to overflow and run wherever it could.

In other words, imagine the port-o-potties at a summer festival. Now tip them over. And now? Imagine there's more than 3 million people who just keep using them.

The practical impacts of Victorian-era air pollution

It wasn't just excrement that contributed to the Great Stink, there was an almost insane amount of air pollution clogging up the skies, too.

For starters, University of Essex professor of economics Tim Hatton says (via The Conversation) that coal was the fuel of choice for the era, and in some areas of Britain, the pollution was so bad it impacted residents' likelihood of developing respiratory illnesses and was even reflected in a person's height — those who grew up in high coal districts were an average of an inch shorter than those with clean air to breathe.

Lee Jackson, author of Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth, told NPR that there were some very terrible, very visible signs of just how bad the air pollution was. When sheep were brought in to graze in Regent's Park, it was obvious how long they'd been there by how black their wool turned. Then, there was the ammonia that rose from the urine in the streets. City shopkeepers complained that the fumes were so strong, their buildings were getting discolored, and anyone walking outside needed to stop to wash their exposed skin at least a few times a day to remove the dirt and grime that settled on them just as they walked through the stinky city.

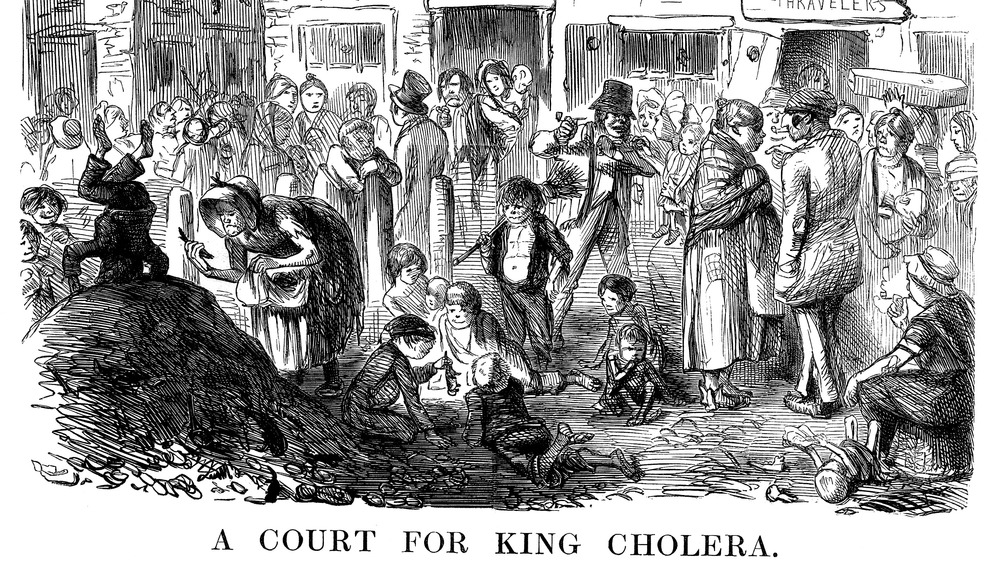

With the smell came cholera

At the time, it was widely believed that bad smells carried disease. It's called the miasma theory, and when 19th century health reformer Edwin Chadwick started trying to stop the cholera outbreaks that were plaguing the city, the measures he introduced were based on the idea that it was the air that was the problem.

And he was — in a way — sort of right. According to the United Kingdom's Science Museum, London saw major cholera outbreaks in 1831, 1837, and 1838. When reformers started trying to clean up what they thought was the problem — the bad smells — they started pushing more towards cleanliness. The state of housing areas were improved, and instances of disease started to drop a bit.

Not everyone was convinced that the bad air was to blame, and when more cholera outbreaks happened in 1848 and 1853, a London doctor named John Snow (pictured) put forward the idea that the source was actually the water. He noticed that most of the people who died in 1854 got their water from the same pump, and he was absolutely right. The raw sewage that was causing the worst of the smell that lingered over London was also contaminating the city's drinking water and spreading disease. Unfortunately for Snow, the data and evidence he presented to the General Board of Health's Committee for Scientific Enquiries failed to convince anyone of anything.

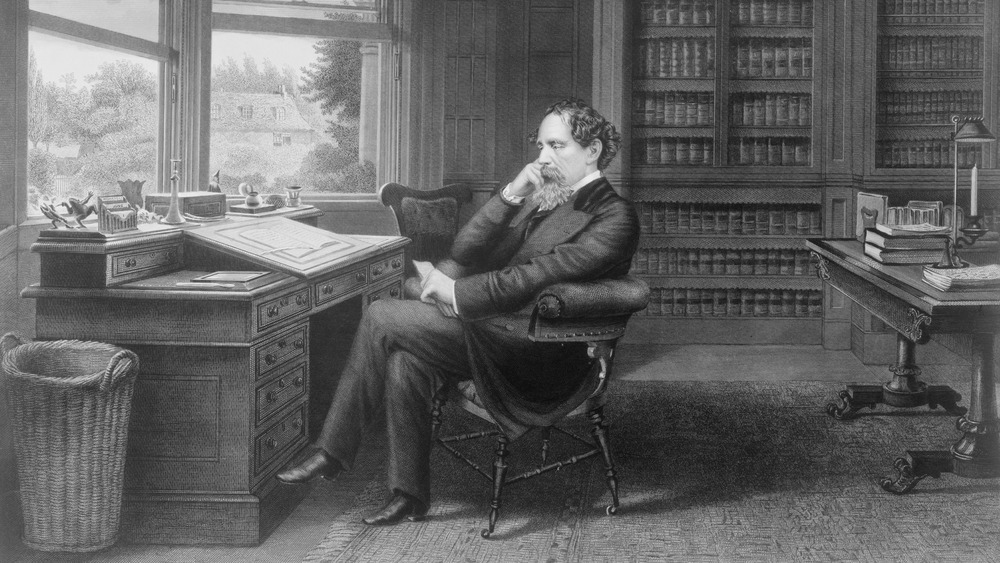

When Charles Dickens tried to fix the stink

When it comes to eye-witness accounts of just how bad it got, there are few better sources than the works of Charles Dickens (pictured). He didn't just describe the filth, according to Martin Daunton, University of Cambridge professor of economic history, he also tried to help kick-start reform programs to clean up the city.

In 1855, Dickens wrote a powerful piece of satire condemning the government's lack of action — and he set it in a town called Cess-cum-Poolton. His candidate lauded the idea of "Be filthy and be fat" and celebrated the idea that cleaning up the streets would be expensive, so might as well keep the money and enjoy it.

Dickens was well aware of the fact that authorities needed to be given a reason to increase spending on health and sanitation and that it was urgently needed. Fortunately, he wasn't alone. When reformer Edwin Chadwick put together his report on just how bad things had gotten, he had some help writing it — from Dickens and his brother-in-law, who submitted some horrific descriptions of the state of the nation's cemeteries.

By the time of the Great Stink, Dickens' editor was on board, too. Household Words ran a piece condemning the pollution of Britain's rivers, where (via Victorian Web) he wrote of the shame of "pollut[ing] them as never before have rivers been polluted since the world was made."

The source of the Great Stink: The Thames

If Charles Dickens was hoping for a way to motivate the powers-that-be to fix the stinking cesspool that London had become, his prayers were answered in the summer of 1858.

According to the BBC, the problems started with a massive heat wave. When June came, it brought with it several weeks of temperatures that reached up to 86 degrees Fahrenheit. Imagine that — and now, imagine the Thames.

At the time, it wasn't filled with just sewage. It was lined with factories — particularly slaughterhouses and leather tanneries — that dumped their waste products right into the river. In addition to the chemicals and the waste animal parts, the Thames contained an unthinkable soup of rotting food (as there was no refrigeration, remember), and worse? The bodies of people who drowned in the river usually stayed there, so there was that, too. (The Guardian says that three years prior, Michael Faraday conducted an experiment where he dropped white paper into the river. It sank less than an inch when it disappeared from view.)

The smell that summer got so bad that Parliament finally came to the conclusion that something needed to be done... those that remained, at least. Some members outright fled the city, while others tried to make their offices at least bearable by dousing their curtains in chloride of lime. It didn't work.

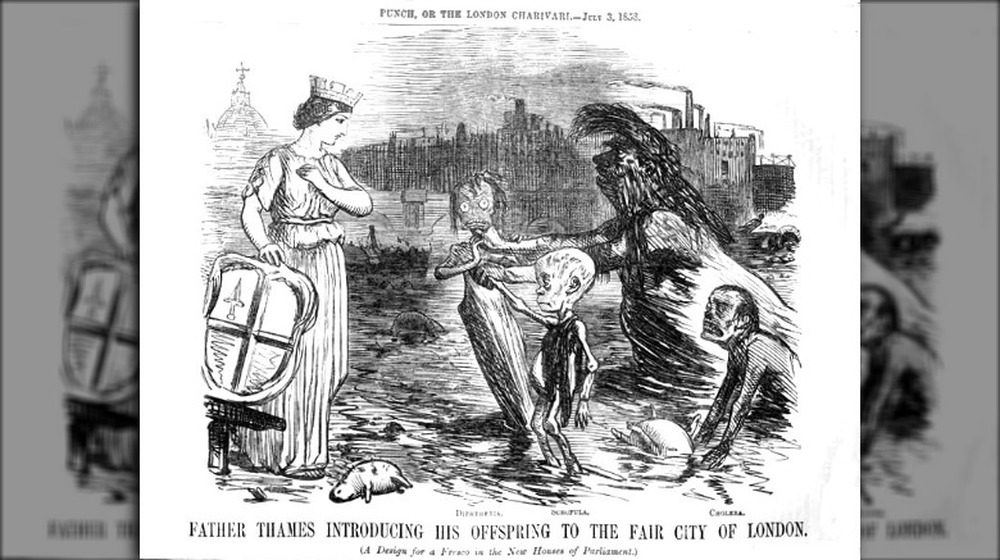

The sad state of Father Thames

Political cartoons of the era pulled no punches and reached back into some seriously old mythology to get their point across.

According to Londonist, the Thames was worshipped by locals long before it was even called the Thames. Archaeological finds thought to be offerings to the river have been dated back to the Iron Age, but it wasn't until around 1713 that the river's spirit was officially given the identity of Old Father Thames. He's mentioned in a poem by Alexander Pope and later depicted in countless statues and works of art that picture him as sort of a mighty, fatherly figure in the style of the ancient Greek or Roman gods.

Until, that is, the 19th century.

By the middle of the 1800s, illustrations of Old Father Thames looked much different. No longer was he a proud, trident-wielding warrior who lorded over his domain. Instead, he had become a filthy, scruffy old man dressed in rags, who was often seen wading through the garbage that his river had become. In one particularly powerful illustration (pictured), he's seen introducing his children — cholera, scrofula, and diphtheria — to the elegant lady representing the city. Clearly, no one was happy about the situation they found themselves in.

The Great Stink led to the most important, city-wide change in London's history

Once parliamentarians were pushed into action by the realization that the river outside their window was fermenting and yes, it did actually impact them, they formed the Metropolitan Board of Works and gave them an insane amount of money to fix London's sanitation problem. At the head of the board was an engineer named Joseph Bazalgette, and fortunately, he'd already drawn up a few versions of the plans for a sewer and was ready to get cracking.

According to The Guardian, this was no small construction project. It included miles of sewers and massive, underground roads that would all ultimately collect and divert not just sewage but rainwater as well. Pumping stations needed to be built to service some neighborhoods, land was reclaimed from the Thames for embankments that hid some of the tunnels, and contemporary media dubbed it "the most extensive and wonderful work of modern times."

Work went fairly quickly, and by 1866, there was only one area of London not connected to the new sewer system — the East End. By the time the project was complete, the Institution of Civil Engineers says it had grown to include 1,382 miles of sewers (which is about the distance between Denver, Colo., and Birmingham, Ala.) along with four pumping stations, an outfall, and three embankments. The last opened in 1879.

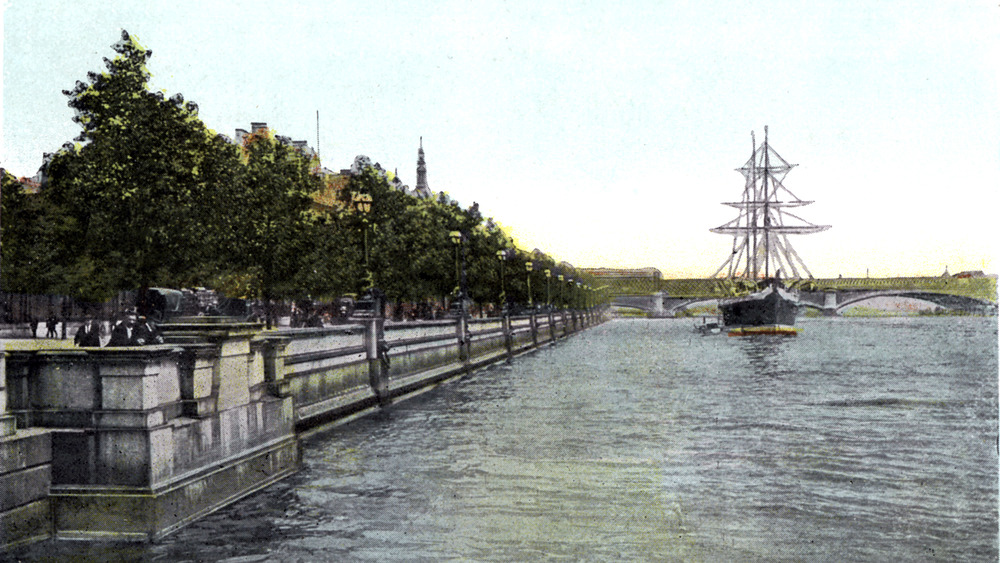

How the sewers changed the landscape of the city

If it wasn't for Joseph Bazalgette's massive sanitation project, London would look incredibly different today — starting with the Thames. According to the Institution of Civil Engineers, Bazalgette's embankments (like the Thames embankment, pictured) served a few purposes — they not only hid underground tunnels, but they also got rid of the river's muddy, mucky banks and opened up previously unusable land. Bazalgette estimated that the city got about 52 acres of land back from the now-narrower Thames (although some estimates suggest it's closer to 22). Historic England says there was another bonus — the embankments helped stop flooding along the riverfront.

It wasn't all good news, though, and not everyone was happy with what this new London meant. Businesses and homes that had once been riverfront property no longer were, and many people who had previously had easy boat access to the river lost that convenience.

And scores of people lost their entire homes and their livelihoods as riverside communities were completely destroyed to make way for progress. These were areas like Cannon Row Wharf, which had been crucial to the coal trade, and an entire swath of buildings near Lambeth Palace. Included in that were the homes on Lower Fore Street, which belonged mainly to poor immigrants who sourced their water from the Thames, and who were among the first victims of the 1848 cholera outbreak studied by Dr. John Snow.

The end(ish) of cholera

Tens of thousands of Londoners died in the cholera outbreaks of the 19th century, and Heritage Calling says that the outbreak of 1853 to 1854 alone had a death toll of 10,738. They also say that after London's new sewer system was finally finished — which happened in the mid-1870s — cholera pretty much vanished from the city.

This isn't all to say that the solution to the problem of what to do with London's poop was the best possible one, as all of these sewers and tunnels weren't taking the sewage to a water treatment plant — they were dumping it into the Thames, just downstream of the water supply. And at the time, they knew it — by the following decade, adjustments to the system were made so that only liquid waste went into the river, and solids were shipped out to the open ocean on barges.

Still, with less waste going right into London's drinking water, the results were clear. And what about Dr. John Snow, the man who said from early on in the tale that the water was to blame? Remember, the guy no one would listen to? He didn't live long enough to see his theory proven correct. After suffering a stroke, he died on June 16, 1858 — right in the middle of the Great Stink (via the BBC).

The tragedy of the Princess Alice

It's arguable that the Great Stink — and, in turn, London's new sewer system — led to what author and historian Angela Jean Young calls (via Londonist) "the worst maritime disaster in Thames history."

It happened on Sept. 3, 1878. The Princess Alice was heading back to London with 750 passengers — many who had just enjoyed a day at the beach — when she collided with another ship and was cut in half. Men, women, and children alike were thrown into the river, and here's where the truly horrible stuff starts. According to the BBC, the crash happened just downstream of the sewage outputs from London's brand new sewer system, and the water into which those 750 people were dumped was filled with excrement. The smell was so bad that the air over the river was toxic — and those who tried to stay afloat were suffocated by the fumes.

Only about 130 people survived the disaster, and one — G.W. Linnecar — later wrote, "Men, women, and children rolled over and clutched and tore at each other; and all through were the ceaseless screaming and appeals for help. How, in such a sudden and unexpected catastrophe, could help be given?"

Bodies washed up along the Thames for days, mostly unrecognizable by the time they were pulled ashore. The disaster prompted changes to the sewage output, as well as changes in navigation routes up and down the river.

Victorian-era sewers, modern problems

London has been using their Victorian-era infrastructure for a long, long time, but that whole saying about history repeating itself? That's kind of happening.

According to Wired, London's population only continued to grow. Their 2.5 to 3 million people of the mid-19th century has since turned into more than 9 million in 2018, and there's another problem — with more buildings having indoor plumbing, that's a huge amount of water for the old system to handle. Bottom line? As of 2018, about 39 million tons of raw sewage was still being dumped into the Thames on an annual basis — undoubtedly, a little not-so-fun fact that Old Father Thames highly disapproves of.

The solution was yet another overhaul of London's water infrastructure, in a project called the Thames Tideway. When it was announced in 2014, it was expected to open in 2023... but the project hasn't been without its detractors. According to The Guardian, debates got heated as officials argued over whether or not the project was worth the money it was going to cost and if the problem was really all that bad.

Go figure. History really does repeat itself.