What Life Was Really Like In An Early European Royal Court

Today, the historic royal palaces of old Europe are a marvel. The sheer size and opulence of these places are stunning sights to see. Most of us couldn't comprehend what it must have been like to live in such a massive splendor. However, there was a good reason why these palaces were so massive — they weren't just housing the royal family but also the entire court. And a royal court could be anywhere from 1,000 people to 10,000 people.

If you were a European aristocrat, the royal court was an exciting place — and often your future depended on it. It was pretty much the center of the country where everything would happen — from politics to romance to scandal to extravagant events. The royal palace was the place to be. But was royal court living really as glamorous and luxurious as it appears? This is what life was really like in an early European royal court.

The rich were expected at court

Nobles of high social standing were very much expected to actively participate in court life. According to Historic Royal Palaces, if you were a member of the elite, being a part of the royal court was mandatory in order to be successful — but it didn't come cheap. In fact, it was downright expensive to maintain the high-maintenance lifestyle of a courtier. But if you could get on the good side of the reigning monarch, the benefits could be endless. It could mean large gifts, titles, positions for family members, or political influence. Being a favorite of the monarch was always the best position a noble could find for themselves — it could mean immense power and influence.

However, it was crucial for a courtier to keep the monarch's favor — which could be a delicate business depending on who the ruler was at the time. A ruler like Henry VIII was a notoriously temperamental king and could be very easily provoked to rage. A monarch's favor could be a very fickle thing. A noble could be on top of the world one moment, but the moment a monarch found something to be offended by, that patronage could be easily and taken away. And having the ruler's ire directed at you could be absolutely devastating.

There was a hierarchy for royal access

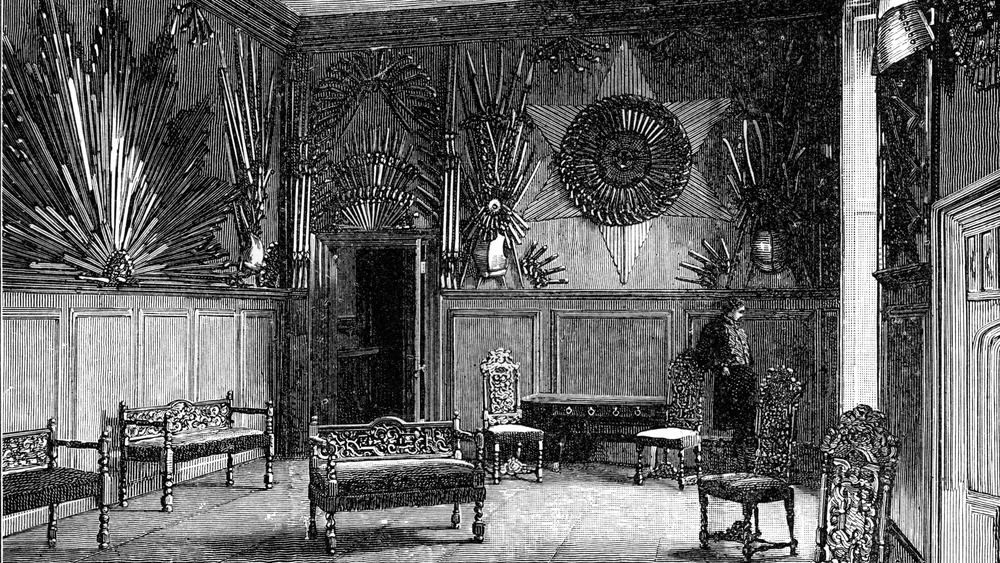

According to Historic Royal Palaces, palaces were massive places that needed to hold the royal family and their servants and the numerous courtiers and their servants. Not only that, but back in the days of old, the ruler's palace was the center of the country. Everything would happen in the royal court — Privy Chamber meetings, the national treasury, national administration, balls, and entertainment all took place under one enormous roof.

And while there might have been crowds of courtiers all living in one huge palace, not everyone had the same privileges. And many palaces were specifically designed to restrict access to the monarch except for the most important of nobles. Henry VIII's Hampton Court was a good example of this. The palace had long rows of rooms with a guard posted at each one — only allowing nobles of the highest rank to speak with the king. Some could make strides to get the king's attention, and usually, the best way to gain an audience with the ruler was a fashionable appearance. The better you looked, the better the chance you had to meet with the king. It certainly brought new meaning to "dress for the job you want."

A place at court was desirable for unmarried daughters

A royal court could also be a hotbed for romance. And it was the ideal place for a single woman to secure an advantageous marriage. Historic Royal Palaces notes that a royal court was practically a modern-day equivalent of a singles' mixer for the nobility. For high-ranking noblemen, obtaining a spot at the royal court for their young daughters could be especially beneficial. If their daughters could make good matches, alliances with other powerful families would mean more wealth, land, and influence. The best place a woman could get in at royal court would be in the queen's household as ladies-in-waiting or women of the bedchamber.

Women who earned places at court were often formally educated, but they also usually had excellent social skills in areas that would bring them attention at court functions. Skills like dancing, singing, and musical fluency were highly prized for a noblewoman as they could bring her prestige and recognition from the courtiers and even from the rulers themselves.

But being a royal mistress could also be advantageous

It was generally expected that the king would have a mistress — or several — but all the while, they would almost always have a wife and queen. Marriages were for politics, but mistresses were for personal pleasure. Many kings kept their affairs semi-private, preferring to keep their mistresses as an open rather than too out in the open. The fact that the king had a mistress was often quietly acknowledged but not vaunted. This is how Henry VIII usually conducted his affairs with his mistresses, at least until Anne Boleyn appeared on the scene. But even a secret mistress could expect to benefit from a relationship with the king and receive expensive gifts or royal favors for her family. And if she was really lucky, when the relationship was over, the king might arrange an advantageous marriage for a former mistress.

However, there was a significant contrast to how mistress relationships were conducted in a court such as Versailles. According to History, a royal mistress could be an official, recognized position in the court of France. And some of those mistresses could obtain political power. One of the most famous was Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV. Even when the two were no longer romantically involved, Madame de Pompadour still remained the king's political advisor and confident. Their relationship lasted 20 years until Pompadour's death.

There were high standards for men, too

A man who was a member of the royal court of a queen like Elizabeth I or Catherine the Great was also held to high standards. They were expected to be intelligent, courteous, graceful, and well-dressed. A queen like Elizabeth I, who had been well-educated throughout her life, would expect her male courtiers to likewise be learned in areas such as literature, history, geography, mathematics, and languages. Male courtiers were also expected to pay tribute to the queen in the form of flattery, courtship, and gifts.

Someone like Elizabeth I never expected any courtship from her courtiers to develop on a truly personal or romantic level — it was really all for show. Elizabeth didn't have any interest in actually marrying and being forced to share her power, but she enjoyed the fun of flirtation and courtship, and she certainly had her favorites at court. However, Elizabeth's enemy outsiders would sometimes get the wrong idea and assume an actual affair was going on rather than an innocent flirtation.

Now, in Catherine the Great's Russian court, the empress didn't exactly hide her romances, not even when she was married. According to Biography, once Catherine was widowed, she never married again but still enjoyed male attention. She enjoyed the company of interesting and good-looking men (though she was a "serial monogamist" and never had relationships with more than one man at a time), whom she was happy to reward with gifts, money, and property when they pleased her.

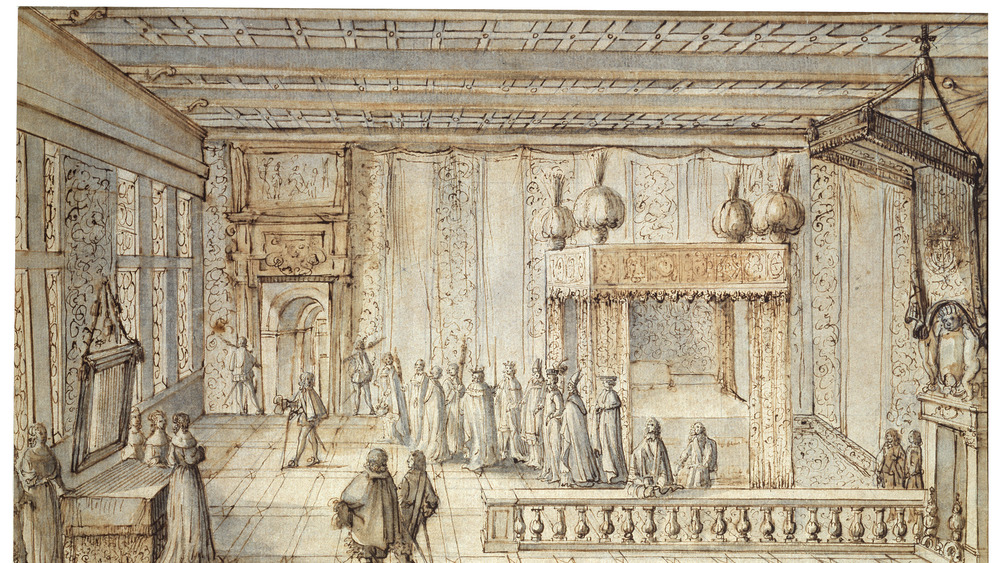

There was always courtly entertainments

Depending on who happened to be the ruler at that time, the monarch often hosted entertainments for the royal court. Rulers like Elizabeth I and her father, Henry VIII, were known for their enthusiasm and support for the arts — naturally, they welcomed musical concerts and performances. Both monarchs were also talented and avid dancers, as well, so balls and masques were typical events for their courtiers. In particular, Elizabeth became a huge fan of the theater during her reign, according to Biography, and often arranged for private theatrical performances.

A royal court could have more outdoor and athletic entertainment like tennis, a historically popular courtly sport, and there would often be a hunting park for deer hunts and hawking. Jousting was also popular — both for spectators and participants. It was known to be highly dangerous and could result in death (Henry II of France died in a jousting tournament), but the significant risks never put a damper on jousting's popularity.

Royal courts often moved around

Many monarchs were known to have several royal palaces — Henry VIII had over 60 homes. So, according to Historic Royal Palaces, it was expected that the royal family and the court would move several times a year to stay at these numerous estates and palaces scattered across the country. Visits to the monarch's many homes could vary in the length of the royal court's stays. Sometimes they would stay at a palace for several months. Other times, they might only be there for a few hours. It all depended on the monarch's wishes.

The courtiers would have to pack up all their belongings and gather their servants from one palace and follow the monarch via horseback. A constantly moving court meant visits to different palaces, but there were other, more disgusting reasons for the location shifts. Palaces that housed so many people became rancid over time and needed to be thoroughly cleaned out. Plus the land and livestock would need time to be replenished.

Bathing didn't happen much

As previously noted, although palaces were enormous, and they housed hundreds of people, things could get tight. And quarters felt even closer, taking into account how people seldomly bathed. At this point in time, bathing was considered unsanitary, so people generally avoided it. Whenever a royal court arrived at a new local residence, it usually wouldn't take long for the smell of unwashed humans to start dominating the palace. This was the reason why many royal courts would move to different royal estates — the royal palaces would become so revolting to the point where they were practically uninhabitable. Versailles was one exception where the royal court stayed in one place — Louis XIV decided he didn't want to travel anymore. But Versailles, for all its gilded glory, became so terribly disgusting over time as it held over 10,000 people.

Henry VIII was one of the few notable European monarchs who took time to regularly bathe and change his undershirt daily. He was a known germaphobe and was constantly waging a neverending war against dirt and bacteria. But Henry was a very rare exception. According to History, Queen Isabella of Castile and Louis XIV only took two baths in their entire lives. Marie Antoinette of France was downright immaculate in comparison, bathing once a month. King James I apparently never bathed at all and was said to be lice-ridden –both his person and his frequented rooms.

Clothes at court were filthy

Much like bathing, laundry was also seldomly done. According to History, the paintings seen today, where nobles are attired in sumptuous clothes, don't show just how disgusting their attire actually was. Many of those clothes were dirty, foul, and possibly crawling with lice. And the odors of that many people with unwashed clothes in an airless room could easily overtake a palace. Historic Royal Palaces notes that a courtier's expensive outer attire often wasn't washed. In the English court of Henry VIII, many wore a linen smock or undershirt to absorb the sweat from their skin (and they needed to bring several smock changes) in order to better protect their fancier clothes. It wasn't terribly effective.

In the times that laundry would be done, the loads were always enormous. There could be over 1,000 people residing at court who all needed their linen smocks and undershirts washed, as well as their disgusting bed linens. To keep up with the demand of so much laundry for a huge number of courtiers, a large group of women was employed to wash everything in the river and let the washing lay out in the sun to dry.

Plumbing at court was abysmal

Reliable plumbing was almost non-existent in a palace at this time. In Versailles, the latrines would become so overwhelmed with blockage and corrosion due to overuse and a lack of cleaning that the pipes would start leaking. And according to History, no room in the palace was safe from the unstable pipes. Leakage could be found in the kitchens and even in the royal bed chambers. Despite being a grand palace, Versailles was actually dirtier than the average slum.

Not only were the latrines overused, but it was even a struggle to get people to actually use the facilities. Not everyone would bother finding the designated area — instead, people (courtiers and servants alike) would simply relieve themselves right where they stood, no matter where they happened to be. Apparently, not even Queen Marie Antoinette could avoid getting hit by human waste when it was being emptied out the window. Even a relatively cleaner by comparison monarch like Henry VIII couldn't fully control everyone else's hygiene habits, much as he tried — with so many courtiers living in the palace, it was impossible to police them all.

Historians are confident that these early royal palaces' horrendous living conditions contributed to a high number of deaths in Europe. Thanks to technological advancement and a shift in hygiene standards, conditions in palaces wouldn't become more sanitary until the 19th century.

Religion could be a major part of court life

It was always the monarch's call, but religion could end up being a critical part of everyday court life. There was usually an expectation in most royal courts that people would attend religious services, but some monarchs were stricter than others when it came to religious adherence. Despite being a notorious womanizer, King Louis XIV of France was also deeply religious and a devout Catholic. And he was most insistent that all of France be a unified Catholic country as well — no exceptions.

One of Versailles's number one rules was that the entire court needed to attend a half-hour daily mass at 10 a.m. As noted on the Versailles official website, the "Chapel Music" choir would play a new piece of music every day at the mass. Sometimes official prayers could happen more than once a day. And courtiers needed to make sure they were present and seen by all.

The Versailles court may have been pretty lax about matters of drinking, gambling, extramarital affairs, and other vices, but skipping prayers or mass was non-negotiable.

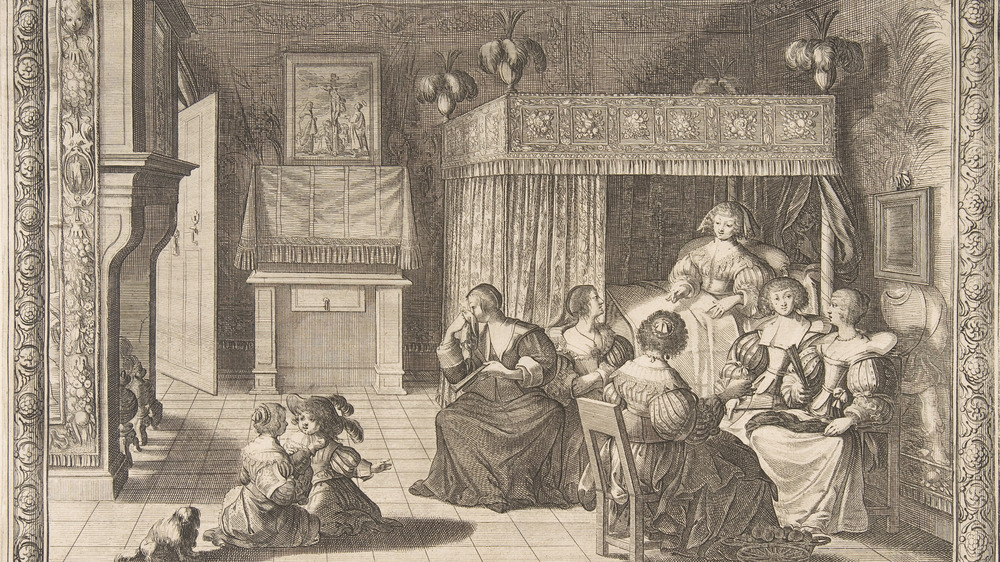

Royal childbirth was almost a spectacle

In a court like Versailles, a royal birth was a huge deal. And the queen or princess could often expect that there would be a crowd of witnesses for the child birthing process. According to the Versailles official website, technically, only doctors, ladies in waiting, the governess of the princes and princesses of the realm, the princesses of the royal family, and a few members of the church were allowed into the royal bed chamber for the viewing. This already seems like too many people by modern standards. But there would be a large crowd of people just outside.

While the birth was actually happening, the rest of the court would be waiting in the other royal apartment rooms, and the doors would be kept wide open. The queen would actually give birth on a special labor bed, which was obscured from view behind a screen. Once the birthing was over, she would be moved back to her own bed. Then, the crowd outside was permitted to enter and bestow their congratulations to the royal family. As if childbirth wasn't enough of an ordeal, the queen had to further endure the presence of the entire court marching through her bedchamber.