What It Was Really Like As A Medic In World War II

Looking at the statistics for World War II reveals some numbers that it's almost impossible to wrap your head around. According to The National WWII Museum in New Orleans, 407,316 Americans died in combat. Even more — 671,278 — were wounded, and it's possible that number should be higher. Let's put that in perspective. The number of dead is the equivalent of the entire population of Minneapolis, Minnesota (via World Population Review). And as for the wounded? That's about how many people live in Nashville, Tennessee.

Still, those are just numbers. They're huge numbers, but they only tell a very small part of the story. Alongside each of those wounded soldiers — and many of the dead ones — were the medics. It was a horrible, grisly job that many were ill-equipped to do... but they did it anyway.

And many brought back lessons with them. When Anthony Acevedo died in 2018, CNN shared the news of his death. Acevedo — a medic and the first recognized Mexican-American survivor of the Holocaust — passed along these words of wisdom based on what he'd seen: "Never repay evil with evil. Remember what my buddies and I went through. Never treat anybody like they're below you. We can't turn a blind eye."

World War II medics shipped out with combat troops

We Are The Mighty says that while World War I was raging, it was called either the Great War, or The War to End All Wars. Some believed it was so terrible that mankind would finally see that they really needed to get their act together and prevent something like this from happening again, but (spoiler alert) that didn't happen.

According to Chapman University, the end of the first war also brought about some hard realizations. The US Army Medical Department decided that thanks to advancements in warfare, the old way of doing things was no longer good enough. To have any hope of saving more lives than were lost, wounded soldiers needed to be treated right where they fell.

That meant changing the way the military's medical personnel was deployed and trained. An overhaul of procedure between the wars meant that military units were now assigned medics that weren't just trained to be medics, but that were trained to work right in the middle of combat. They went through military training just like other soldiers and they were soldiers themselves. Medics that enlisted pre-WWII were sometimes given their medical training in non-combat situations, but eventually, others were just thrown into the fire.

Sometimes medics were left alone... and sometimes, they were a target

The medic's helmet that's in the collection of the National D-Day Memorial is a rarity: Google Arts & Culture says not many are still around, partially because the symbol of the red cross on the white background didn't always have the intended effect. A typical battalion would be made up of between 400 and 500 men, and along with them would be somewhere around 30 medics. The idea of labeling them so clearly was that their own men would be able to easily find them in the chaos of battle, and honorable enemy soldiers wouldn't target them.

War History Online says medics in different theaters faced different attitudes. Those fighting in North Africa generally avoided attacking medical teams, and in conflicts across Western Europe, the same courtesies were often (but not always) given. They give the example of one incident in 1945, when American troops came across a German medical team that had gotten stranded. Not only did they not engage, but they filled up the German team's vehicles with gas and sent them on their way. Canadian troops, on the other hand, were notorious for shooting at medics: in part because they knew most German medics were armed.

But in the Pacific, things were much different. Both sides considered any member of the opposing forces as fair game.

The most powerful new weapon in the WWII medic's arsenal

It might seem like a given that most people who die in war die of things like bullets and combat wounds, but according to Peter C. Doherty, Laureate Professor at the University of Melbourne (via The Conversation), pre-WWII soldiers were more likely to die of disease or infection than of injuries sustained in combat. By the end of WWII, that had shifted — only one of every nine casualties was due to infection.

That was largely due to the presence of one very powerful tool in the medic's arsenal: penicillin. According to National Geographic, the first person to be successfully treated with penicillin was in 1941, when it was still hard to produce. When the drug ran out, the patient died — but with war looming, experts knew they needed to find a way to mass-produce it. And they needed to find it fast. Fortunately, a series of fortuitous breakthroughs meant that by 1944, huge amounts of penicillin were being shipped off to the war. But what was used before that?

According to HistoryNet, medics first relied on something called sulfa. That's the yellow powder eagle-eyed movie buffs will see silver-screen medics using to treat wounds, and it worked... for a while. Sulfa drugs — which were invented by a German pathologist — were so overused that diseases became resistant, which is when penicillin sort of stepped in.

WWII medics were often caring for the wounded... while wounded themselves

Edwin "Doc" Pepping was part of Easy Company, 2nd Battalion — the group that was later immortalized as the Band of Brothers. The US Dept. of Defense says that on D-Day, he jumped from his transport plane just 300 feet off the ground and suffered three cracked vertebrae and a concussion. He moved on to an aid station near Utah Beach, spent hours tending the wounded, and saved the lives of an estimated 80 soldiers.

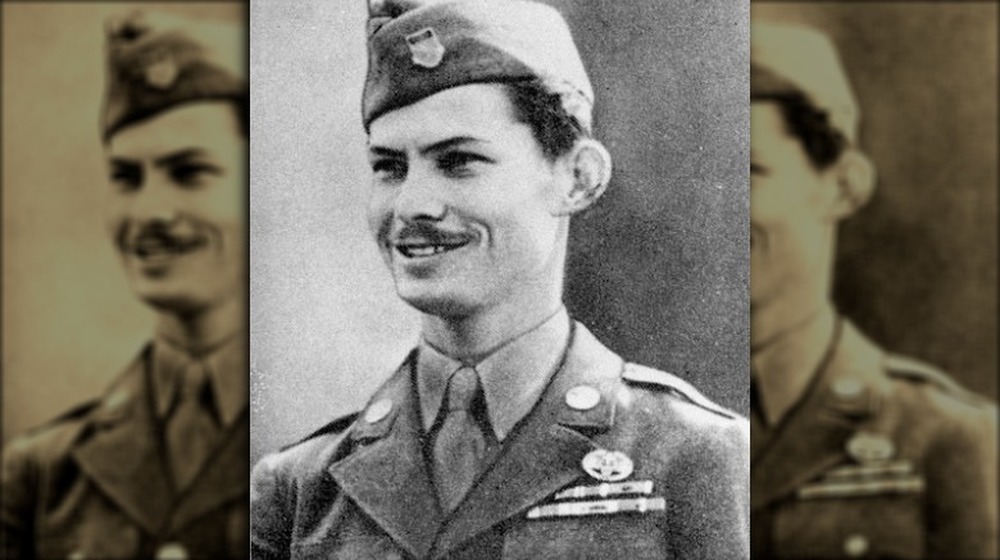

His isn't the only story of incredible perseverance through what must have been incredible agony. When 24-year-old Ray Lambert (pictured, right) and his team of medics headed onto Normandy Beach with the first wave of troops, he was immediately shot. The bullet shattered his right arm, and NPR says that's when he started trying to save the soldiers that were falling quickly. It was also when he was shot again. This time, it was his leg. He cinched himself up with a tourniquet and kept going, wading into the water to rescue drowning soldiers. That's when the ramp of another landing craft caught him and crushed part of his spine... and still, he kept going.

Lambert survived the war, and in 2019, the 98-year-old veteran returned to the beach. The rock that he, his men, and the wounded soldiers they saved took cover behind has a plaque on it now, and it's known as "Ray's Rock."

WWII medics were often fighting at the same time they were trying to save lives

Saying that a WWII medic had to be good under pressure is an understatement: since they were deployed alongside their units, it was often up to them to head out into the line of fire and try to save their fallen friends. Ben L. Salomon was a dentist when, according to the Jewish Virtual Library, he was drafted in 1940. He was put in charge of a machine gun unit in the 102nd Infantry, and was eventually moved to the Dental Corps.

Fast forward to 1944 and Saipan, when Salomon volunteered to step in as the 2nd Battalion's surgeon. After the Japanese commander ordered all his soldiers — estimated to be somewhere around 6,000 men — to take out the 2nd, Salomon found his aid station besieged. At the same time he struggled to save the lives of the 30 men who had been brought to him, he shot and killed the Japanese soldiers who had found his medic's tent.

Originally trying to find able-bodied men to help him defend the position, he eventually ordered a withdrawal — while he grabbed a machine gun and covered their escape. When the fighting was over, the National Museum of American Jewish Military History says that his body was recovered from where it had fallen alongside the 98 enemy soldiers he'd killed in an attempt to protect his patients.

Samuel Beckett's recollections of WWII medics

In 1945, the Irish Red Cross dispatched an entire military hospital to St-Lo, France (pictured, after the bombings). The 60 workers found little more than ruins, and according to RTE, the arrival of the Irish hospital workers was taken by locals as a sign that their town hadn't been forgotten after all.

And that's the important thing here: according to The Irish Times, future novelist Samuel Beckett was recruited to work mainly as an interpreter, and ended up writing extensively on the impact the medics and hospital staff not only had on the sick and the injured, but on the town as a whole.

They represented life, especially for one mother who named her son Patrick in tribute to the workers who had come — even though 90 percent of the town was gone — and delivered around 200 babies in the year they were there. Beckett described (via BMJ) those the hospital cared for, and they weren't just war wounded, they were civilians injured in air raids, they were people trapped in collapsed buildings, and townsfolk now susceptible to illnesses like tuberculosis. Most heartbreaking of all, he talked about the children who played with unexploded bombs and munitions, telling the tale of how medics' jobs continued long after the fighting stopped. They didn't just bring bandages, they brought hope.

The unlikely friendship between a German doctor and a boy from Iowa

When it came to what soldiers got treated by what medics, there were plenty who looked past the uniform and just saw a wounded man in need of help. Take the story of Elmer Richardson. Originally deemed an essential stateside worker, he wasn't drafted until 1944. He was sent to the 12th Infantry, and found himself on the front lines of what would later become known as the Battle of the Bulge.

That, says the Des Moines Register, is when he found himself in the middle of a German ambush, and was gut-shot — a wound that's usually a death sentence. He was taken into German custody, ended up in Helenenburg, and was sent to a hospital run by — of course — German medical staff. Fortunately for him, Ludwig Gruber only saw a man suffering from severe internal injuries, and spent hours repairing the damage and rebuilding his bowel.

Richardson recovered, and gave the doctor his address. He asked Gruber to write to him and let him know if he made it through the war. They both survived, and — as promised — wrote each other. Richardson ultimately died in 1996 and Gruber in 1998, but when Richardson's son retraced his father's wartime route through Europe in 2015, he found — and met with — two of Gruber's sons. Steve Richardson later said, "I felt like I gained three brothers."

Some WWII medics died before they got the 'thank-you' they deserved

The moment Waverly B. Woodson disembarked from his landing craft on D-Day, he had been fairly certain he'd been killed. The soldier next to him was killed, and the shell that destroyed their boat even as they waded into the water sent so much shrapnel into him that for a moment, that's all there was.

Then, he hauled himself up onto Omaha Beach, and spent the following 30 hours tending to the other wounded soldiers who had injuries that he constantly put before his own, even returning to the water to save several men from drowning. In those 30 hours, he saved around 200 lives before finally collapsing from exhaustion. That, says History, wasn't the end: once he recovered his strength, he returned to the beach to help more.

Woodson was hailed as a hero in American newspapers, but there was no Medal of Honor waiting for him — and in fact, there was no Medal of Honor given to any one of WWII's more than one million black soldiers. In 2020, Maryland Senator Chris Van Hollen has said. "His valor was never fully recognized due to the color of his skin. That's unacceptable." Van Hollen has introduced legislation that would allow for a posthumous Medal of Honor. Woodson died in 2005, but his widow continues to fight on his behalf, and has said she will donate his medal to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Desmond Doss: from conscientious objector to Medal of Honor recipient

The National WWII Museum says there were around 25,000 conscientious objectors who were drafted into non-combat positions, and that included becoming medics.

That group of people included Desmond Doss, a Seventh-day Adventist who went through basic training, skipped weapons courses, and was relentlessly abused for his faith. His fellow soldiers and commanding officers alike threatened him with everything from "... when we get into combat, I'll make sure you don't come back alive," to dishonorable discharges, but he stuck it out and in 1944, was sent to the Pacific alongside the 307th Infantry — some of the same men who had threatened him. In his first two battles — Guam and Leyte — he earned two Bronze Stars for valor, and then, it was on to Okinawa.

There, he participated in what NPR calls "one of the bloodiest battles of World War II in the Pacific,": Hacksaw Ridge. Even as he dragged wounded soldier after soldier to safety, he prayed — "Lord, please help me get one more." — and was ultimately credited with saving 75 men who were too severely injured to obey orders to retreat. Doss was wounded by a sniper, contracted tuberculosis, and was sent home to receive the Medal of Honor.

Gisella Perl: the medic of Auschwitz

Before the war, Gisella Perl was a gynecologist. She had spent her whole career helping women, but when she was sent to the Hungarian Women's Camp in Auschwitz, her medical background brought her to the attention of Dr. Josef Mengele (pictured).

Mengele put her in charge of discovering and reporting all pregnant women in the camp, and it wasn't long before Perl realized why he wanted them. She wrote (via the BBC): "[Mengele] was free to do whatever he pleased with us," and that included forcing her to remove and preserve a woman's eight-week-old fetus. When she saw a group of these women being beaten by soldiers before being pushed — alive — into the camp's crematoriums, she knew she needed to protect as many of them as possible.

Perl wrote about her realization: "It was up to me to save the life of the mothers, if there was no other way, than by destroying the life of their unborn children." And that's exactly what she did, while performing the duties of camp doctor and assistant to Mengele. She was ultimately transferred to Bergen-Belsen, and after it was liberated, she stayed to help. She later returned to medical practice, specializing in helping Holocaust survivors who were suffering from infertility issues.

The Jewish medic who treated Nazi soldiers

Pfc. Louis Cooperberg was just an ordinary guy who found himself in extraordinary circumstances, and in August of 1944, he wrote a letter to his little sister. Eleanor was back home in Brooklyn, and after reassuring her that they'd see the end of the war soon, he talked about operating on the Nazi soldiers brought into his unit.

It was after he cleaned out a damaged piece of an SS trooper's brain that he wrote (via HistoryNet), "What glory for Hitler! I've seen chunks of shoulder missing; guts hang out of open stomachs; missing feet, legs, arms, what glory in war? Yet they fight..." He could speak German fluently enough that he could talk to them, but was at a loss of what to say. He'd seen the worst of the worst: farmers gave their daughters to German soldiers in exchange for their lives, the devastation of entire cities, children caught in the crossfire.

But then, wounded German soldiers were sent to them. Cooperberg wrote: "They have robbed and murdered and raped, and they lie on my slab, innocent like and in pain ... and despise me because I am a Jew. But I treat them. ... An SS trooper arrogantly refused a blood transfusion because it was American blood, we forced it into him, we should have let him die. ... But I can't explain that. How can you hate one defenseless man?"

From college to concentration camp

The end of the war brought a whole new horror: the liberation of the concentration camps, and the full realization of what had been going on there for years. Bergen-Belsen was liberated in April of 1945, and in addition to the more than 10,000 bodies that needed to be buried, there were 43,000 survivors.

In May, 95 medical students from London were recruited, and according to the BBC, they were originally told that they were going to be caring for Dutch children, and it wasn't until they got there that they realized they were going to be faced with huts, filled with the sick, the malnourished, and the dying. It was 23-year-old John Reynolds who wrote, "People in all stages of disease. Many were dead. Practically all were emaciated. [They were] treating the dead as furniture and their beds as latrines."

Part of their morning duties were to go into their assigned huts and remove those who had died during the night. They were there until the end of the month, and then, they were sent back to London and civilian life. They were never the same, and neither were their patients: according to King's College London, the daily death toll dropped from 500 to 50. Reynolds later wrote of the successes in his journal: "The morale of the internees became very high and more and more became able to fend for themselves, became stronger in mind and body and regained some sort of decency."