The True Story Behind Tokyo Rose

During World War II, Tokyo Rose was infamous among American GIs for seductively predicting their downfall, whether it was due to infidelity, sterility, or in battle. But for all the stories told about Tokyo Rose, there's little evidence that she actually existed. Despite this fact, the United States government insisted on turning Iva Toguri d'Aquino, a U.S. citizen who refused to renounce her citizenship during the war, into Tokyo Rose during the 1940s and 50s when they prosecuted and convicted her for treason, per Courthouse News. Toguri ended up serving a little over six years in prison and was repeatedly threatened with deportation after her release.

Toguri later said that while the trial was going on, she "wasn't all that worried [about being found guilty of treason]. I did not feel the least bit as though I had betrayed America." Many at her trial also believed that she would be acquitted, but the U.S. government, from the FBI to the judge presiding over her case, wanted her labeled a traitor.

Toguri was eventually pardoned when it was revealed that the trial had been laden with perjury and that the federal government had actively covered up evidence of Toguri's innocence. As a result, Toguri became the first person to ever be pardoned for treason. This is the true story behind Tokyo Rose.

So who was Tokyo Rose?

Although Iva Toguri became famous as "Tokyo Rose," there wasn't a single person who was actually Tokyo Rose. Instead, the name referred to about 20 separate women who were making English-language radio broadcasts during World War II "aimed at demoralizing American soldiers serving in the Pacific."

According to GIs, Gender, and Domesticity during World War II, by Ann Elizabeth Pfau, most of the servicemen's memories of Tokyo Rose's broadcasts were often based more on "the collective experience and shared culture of American military personnel" than the actual broadcasts themselves. As a result, "Tokyo Rose" became an American fabrication, "a female villain who articulated emotions the servicemen were unable or unwilling to acknowledge."

In Tokyo Rose/An American Patriot: A Dual Biography, author Frederick P. Close notes that not a single Japanese broadcaster called themselves "Tokyo Rose." Instead, any woman heard on Radio Tokyo, and later in Shanghai, Manila, and Java, was called Tokyo Rose by American GIs. Close even describes Tokyo Rose as a "radio version of the sirens that tormented Odysseus and other ancient mariners." Although there were women broadcasters occasionally across the Pacific, the accounts from GIs about the contents of Tokyo Rose's broadcasts didn't line up with the existing recording and transcripts.

Variations on Tokyo Rose

Japanese women weren't the only ones given a nickname by American servicemen during the World War II. Women who put out English-language radio broadcasts to demoralize European troops were known as Axis Sallys. There were at least two known Axis Sallys, Rita Zucca and Mildred Gillars.

According to HistoryNet, Gillars was from Ohio and was broadcasting from Berlin, Germany, while Zucca was a New Yorker who was broadcasting from Rome, Italy. Although the GIs had various names for the women on the radio, including "Berlin B*tch" and "Berlin Babe," Axis Sally was the one that stuck in the media. While Gillars ended up convicted for treason and sentenced to 10 to 30 years, Zucca had renounced her American citizenship, so the attempts to build a treason case against her were dropped by the FBI. Gillars, meanwhile, served 12 years in prison until she was paroled in 1961. Upon her release, she became a teacher at a convent in Ohio.

Even after World War II, Americans persisted in giving people these kinds of epithets. During the Korean War, Anna Wallis-Suh from Arkansas who put out English-language propaganda from North Korea was known as Seoul City Sue. During the Vietnam War as well, Trịnh Thị Ngọ, who put out English-language broadcasts for North Vietnam, was known as Hanoi Hannah.

The broadcasts of Tokyo Rose

The broadcasts of Tokyo Rose ranged in content from things like stroking the GI's fears about their wives infidelity to warnings of gas attacks. The Washington Post reports that millions of servicemen heard broadcasts about false battle outcomes, cheating spouses, plus versions of pop songs to keep the GIs listening.

According to GIs, Gender, and Domesticity during World War II, the broadcasts from Tokyo Rose seemed to materialize the worst fears of the GIs. But according to James G, a former lieutenant, although the servicemen initially laughed at Tokyo Rose's broadcasts, after her predictions of Japanese air raids proved to be accurate, the Americans started to treat her broadcasts as truthful premonitions.

In August 1944, Tokyo Rose reportedly started a rumor that a gas attack was coming, which "triggered a run on gas masks among the anxious servicemen who prepared themselves for the attack and by their actions gave further credence to the warning." However, FBI case files reveal that none of these rumors were started by Tokyo Rose, and instead they were merely "speculation on the part of [American] troops."

Although rumors of upcoming gas attacks continued to spread around the Pacific, "there is no evidence that Radio Tokyo broadcasts ever warned American soldiers to prepare for such an attack, and the Japanese military never used chemical weapons against American troops." Other rumors that GIs claimed originated from Tokyo Rose was the idea that the antimalarial drug Atabrine made men sterile or impotent.

Who was Iva Toguri?

Iva Ikuko Toguri D'Aquino was born in Los Angeles, Calif., on July 4, 1916. Her parents, Jun and Fumi Toguri, were both Japanese immigrants, but her father wanted their family to assimilate into American culture, so growing up Toguri was discouraged from learning Japanese. Her father also insisted that she use a fork rather than chopsticks, and meals were often a fusion of Western and East Asian dishes, says HistoryNet.

According to Justice Denied, Toguri planned on becoming a doctor, and in 1940 she graduated from UCLA with a bachelor's degree in zoology. Even the FBI website reports that Toguri "was a popular student and was considered a loyal American."

In the middle of 1941, Toguri was sent by her parents to be "the family's representative" for the upcoming death of her maternal aunt. Although she was too pressed for time to apply for a passport or a visa, she was given a certificate by the U.S. State Department, which gave her permission to travel and return, and was told that it would be good enough. On July 5, a 25-year-old Toguri left for Japan.

Wrong place at the wrong time

Iva Toguri planned to stay in Japan for just one year, and in September 1941 she applied for a U.S. passport from the U.S. Vice Counsel in Japan. Despite the fact that she couldn't read the local newspapers and didn't know the extent to which tensions were rising between the U.S. and Japan, Toguri soon realized that the situation was precarious and made arrangements to return to America, writes Hans Sherrer.

However, when she tried to board a ship on December 2, 1941, she was told that "the Certificate of Identification provided by the State Department wasn't considered proof of her U.S. citizenship." Five days later, the Imperial Japanese Army bombed Pearl Harbor.

Toguri was already having a difficult time in Japan since she didn't speak the language, and now she was stuck there during a war. Japanese government agents were suspicious of her and told her to renounce her U.S. citizenship. However, although Toguri refused and asked to be put in the internment camps with other "enemy aliens," Japanese officials denied her request "due to her ancestry and gender," History Net reports. According to The Washington Post, they also denied her a food-ration card.

Soon after, she had to move out of her aunt's house because neighbors believed her to be a spy for the Americans. And in the summer of 1943, Toguri ended up in the hospital due to malnutrition, scurvy, and beriberi.

Iva Toguri's 340 broadcasts

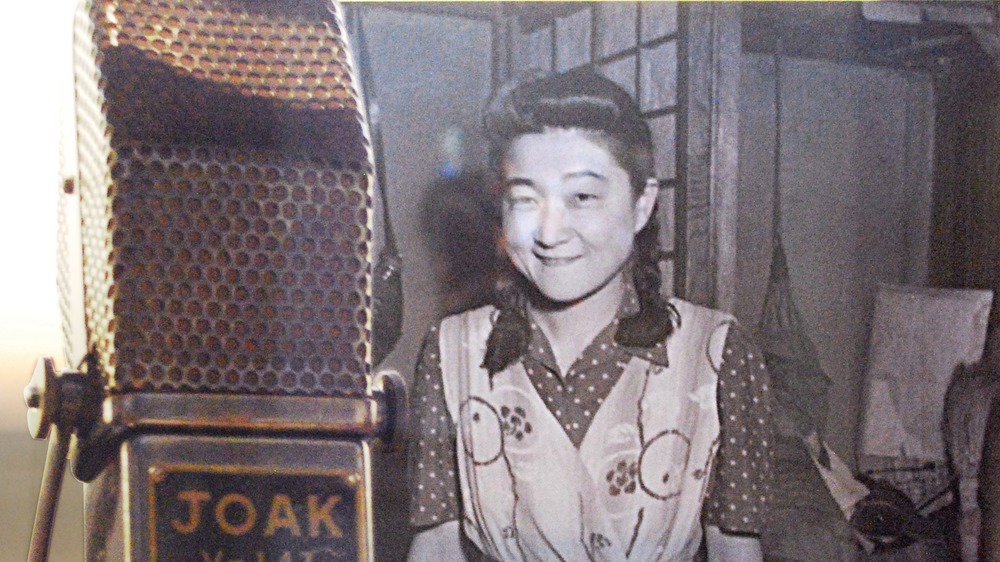

After her hospitalization, Iva Toguri tried once more to find a job in order to pay off her debts and answered an advertisement for English-language typists at Radio Tokyo. It was there that she met Maj. Charles Hughes Cousens, a British POW who was being forced by the Japanese to put out English-language propaganda broadcasts for Radio Tokyo on a program called Zero Hour.

Justice Denied writes that Toguri ended up gaining Cousens' trust because she was smuggling medicine and food to the Zero Hour crew, as well as other POWs. She was also the only one at Radio Tokyo who had refused to renounce their American citizenship, so when Cousens was ordered to include a woman broadcaster, he suggested Toguri.

But Cousens had a subversive plan, intending to "undermine the Japanese effort by nuance and sarcasm." And even though Toguri didn't have a choice once she was ordered to be a broadcaster, she understood Cousens' plan and was eager to play along. According to a broadcast from Aug. 14, 1944, she even referred to her own program as a "chapter of sweet propaganda." According to the FBI, her program may have even raised Army morale.

Referring to herself as "Orphan Ann," Toguri's broadcasts lasted no more than 20 minutes and most of it was music, in-between which she read from a script prepared by Cousens and later herself. The worst thing Toguri actually ever said was when she playfully referred to U.S. soldiers as "boneheads."

Tokyo Rose discovered

After World War II ended, reporters set off looking for Tokyo Rose, though they soon realized she didn't exist. However, a few did learn about Iva Toguri's broadcasts. According to "American Hero & Stoic: Tokyo Rose?" by Erik Brown, Harry Brundidge of Cosmopolitan Magazine and Clark Lee from the International News Service interviewed her for four hours. Toguri was offered $2,000 for her 1945 interview (almost $30,000 in 2020), which was likely her biggest incentive to go along with their framing of "Tokyo Rose," but she never ended up being paid.

Because of the interview, Toguri spent over a year at Sugamo Prison in Tokyo, during which time she was only allowed a 20-minute visit with her husband Felipe d'Aquino once a month. Upon her sudden release, Toguri applied for an American passport again. Although the State Department said that it had "no objection at all" to issuing Toguri a passport, Americans such as Walter Winchell and Harry Brundidge started plotting with J. Edgar Hoover to prove that Toguri was in fact Tokyo Rose and to prosecute her for treason.

During this time, Toguri became pregnant, but because she was "in such a weak condition after her prison sentence," she lost the baby, as per Medium. Soon afterwards, Brundidge arrived in Tokyo and convinced Toguri to sign Lee's notes from the interview "as authentic," claiming it would help speed up her return. But after Brundidge returned to America and published a series accusing Toguri of being Tokyo Rose, the Justice Department issued an indictment.

The seventh person convicted of treason

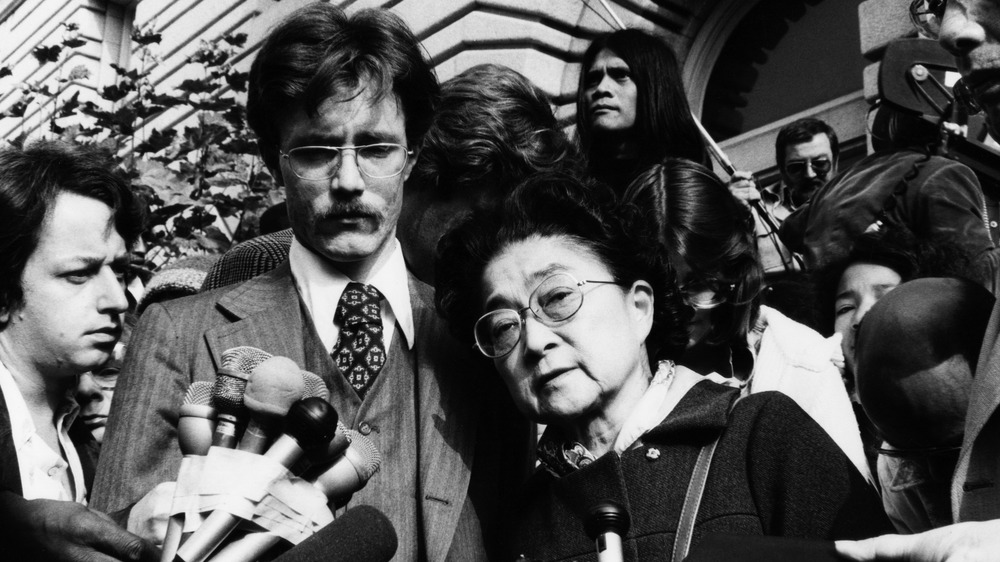

Iva Toguri was arrested by military police in Tokyo, and on Sept. 25, 1948, she finally managed to make it back to the U.S. Unfortunately, it was "as an accused enemy of the United States." Courthouse News Service writes that Toguri's trial ended up being the most expensive trial of its time, costing $750,000 over the course of 13 weeks.

According to The National Registry of Exonerations, on Sept. 29, 1949, the Federal District Court in San Francisco found Toguri guilty of one count of treason out of eight, making her the seventh person in the history of the U.S. to be convicted of treason. In the verdict of D'Aquino v. United States, the "overt act" that Toguri was found guilty was that "on a day during October, 1944, the exact date being to the Grand Jurors unknown, said defendant, at Tokyo, Japan, in a broadcasting studio of the Broadcasting Corporation of Japan, did speak into a microphone concerning the loss of ships."

Notably, none of the other POWs who'd been a part of Radio Tokyo were charged with treason, even those who had renounced their American citizenship.

A fiasco of a trial

Iva Toguri's trial was a fiasco from start to finish. According to Justice Denied, when she arrived in San Francisco, the FBI removed her from jail and tried to interrogate Toguri without her lawyer present. Prosecutors also intimidated and pressured countless witnesses. "Nobody went into that courtroom as a witness for the prosecution that wasn't under terrible pressure to perjure themselves," writes Courthouse News Service.

Even the indictment was based on perjury. But when the defense uncovered evidence of this, "U.S. District Court Judge Michael Roche ruled it was harmless error because the witness wasn't a trial witness." In addition, the defense wasn't allowed to present any evidence to the jury that had to do with how Toguri helped POWs by giving them medicine and food during her time in Japan, since Roche ruled "it was irrelevant to the treason charges."

The most unconstitutional part, other than everything about the trial, was the fact that even though the trial ended in a hung jury, Roche demanded that the jury come up with a verdict. He ordered the jury to continue their deliberations until they came up with a verdict, because they weren't spending over half a million on a mistrial. Roche even admitted later that "he'd been prejudiced against her from the trial's inception."

Tokyo Rose receives a presidential pardon

Iva Toguri was sentenced to ten years in prison, fined $10,000, and had her U.S. citizenship revoked. Since her husband had testified at her trial, he was barred from entering the U.S. again, and as a result they never saw each other again after her conviction.

Toguri spent seven years in prison before she was granted parole on Jan. 28, 1956. And as soon as she was released, Justice Denied writes that she was served a deportation warrant. Although many advocated on her behalf and opposed her deportation, it took two years for the immigration service to say that they were "ceasing efforts to deport Iva."

Although Toguri had submitted two applications for presidential pardons, once during her imprisonment and once after her release, they had both been denied. But in 1976, filmmaker Antonio Montanari, Jr., reporter Ron Yates, and other independent investigators were able to uncover evidence proving federal prosecutor's egregious mishandling of the case. As a result, acting on the recommendation of U.S. Attorney General Edward Levi, President Gerald Ford pardoned Toguri on Jan. 19, 1977, over 20 years after her release from prison, making her "the only person convicted of treason in this country that has been pardoned."

With the pardon, Toguri's citizenship was restored, and the deportation threats finally ceased. Toguri had moved to Chicago after her release from prison, and she lived there until dying of natural causes at the age of 90 on Sept 26, 2006.

America's own Rose

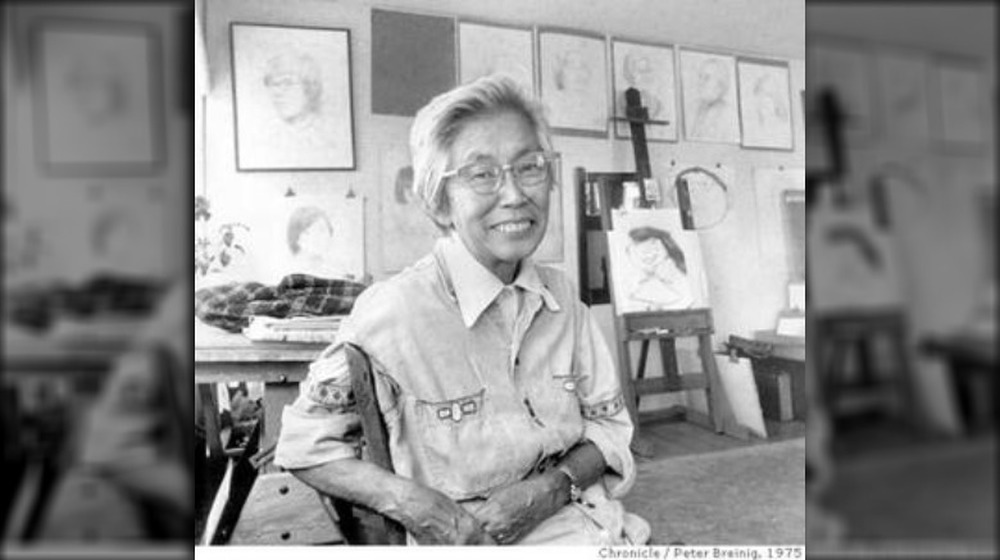

Broadcast propaganda wasn't unique to the Axis powers during World War II. The United States actually had their own woman broadcaster who was later called "America's Tokyo Rose." Born in Innoshima, Japan, in 1908, Mitsu Yashima and her husband came to the U.S. on tourist visas right before the beginning of World War II.

Since Yashima and her husband Taro were living in New York, they weren't subject to mass incarceration like people of Japanese descent on the West Coast. Instead, they were recruited by the United States government. According to The Unsung Great: Stories of Extraordinary Japanese Americans, by Greg Robinson, Yashima created Japanese-language radio broadcasts for Japanese women, "urging them to commit sabotage and do what they could to stop Japan's military machine."

After the war ended, Congress passed a special bill in 1948 that allowed the Yashimas to stay in the U.S., "as a reward for their wartime work." Their son, Mako, was also given permission to join them, since he had been left in Japan when they came to America. During the second half of the 20th century, the Yashimas illustrated and wrote several children's books together.