How A Death Ray Turned Into Radar

Sometimes scientific inquiry doesn't lead where you expect it. That's what happened when, in the 1930s, Great Britain found itself in a desperate predicament. Military experts were warning that the next war would be dominated by air power. And the unique strategic advantage that the British enjoyed as an island nation was quickly dissipating, as it became a target for aerial bombardment under the new conditions. Great Britain was accustomed to defending its borders from external attacks, but for centuries those attacks came by sea, and England maintained a powerful navy. With advances in aircraft technology and the rise of Nazi Germany, the British all of the sudden felt exposed and at risk of attack.

Faced with a growing threat from Germany and the reality of enemy airfields just 20 minutes away, Britain's Air Ministry set up the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence (CSSAD) in 1934. The new committee was tasked with launching several projects with an eye toward diminishing the air threat. Among them was a race to develop a high-tech "death ray" that would be powerful enough to knock enemy planes out of the sky, according to the Royal Society. It was a race that was fueled, in part, by reports that the Nazis had already developed a death ray that was capable of destroying entire towns and killing hordes of people — all with the push of a button, according to Futurism.

The end of death ray hopes

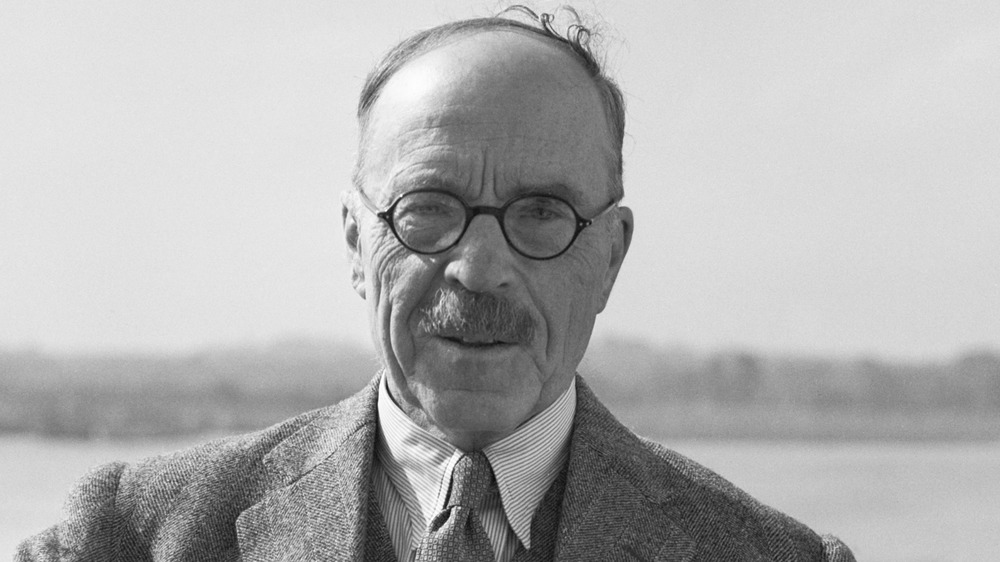

The CSSAD appointed Sir Henry Tizard (pictured above), the distinguished Oxford-trained chemist, to chair of the program. He was asked to determine whether or not it was possible to create a particle beam or electromagnetic weapon that could blow up a plane's bombs, jolt a pilot to death, or altogether burn up an aircraft while in midair. The team came up empty handed. So desperate was the Air Ministry, they eventually turned to the public and, according to the American Physics Society, offered £1,000 to anyone who could kill sheep from 100 yards away. Again, nothing.

In 1935, two scientists at the Radio Research Station, Robert Watson-Watt and Arnold "Skip" Wilkins, quickly determined that it was theoretically possible to create a so-called death ray. They also determined the power requirements were beyond what modern technology would allow. That recognition meant the British would never get their death ray, but it also meant the Nazis didn't have one, either.

How radar saved Great Britain from the Nazis

Watson-Watt and Wilkins may have failed to develop a weapon, but their efforts did result in a new research direction. It was, as Watson-Watt wrote in a memo, "the difficult, but less unpromising, problem of radio-detection as opposed to radio-destruction," according to the American Physics Society. The two had a theory that it might be possible to develop an aircraft detection system by transmitting and receiving a signal back from an incoming plane. It was no death ray, but the ability to detect incoming planes without having to see them with the naked eye would change the nature of air warfare.

Watson-Watt and Wilkins called their invention RDF (Radio Detection Finding), or what the Americans later called radar (RAdio Detection And Ranging). It turned out that radar would save Great Britain from Nazi bombers in the summer and autumn of 1940 during the Battle of Britain. Germany's campaign failed and they had lost nearly 2,000 planes, which accounted for nearly half of their fleet, according to Air Force Magazine. As a result, Hitler was unable to establish the country's air dominance and refocused his attention on ground war by invading Russia.