What It Was Really Like Working On A Whaling Ship

Certain aspects of our daily lives seem permanent. Even as the future arrives in slow motion, we assume the fundamental shape of our lives will remain the same. The cars might become electric and self-driving, for example, but we assume we will always be using cars of some sort. This applies to the industries that sustain modern life. It's hard to imagine a world where the oil and gas industry isn't a thing—how can something so vast, valuable, and necessary ever go away?

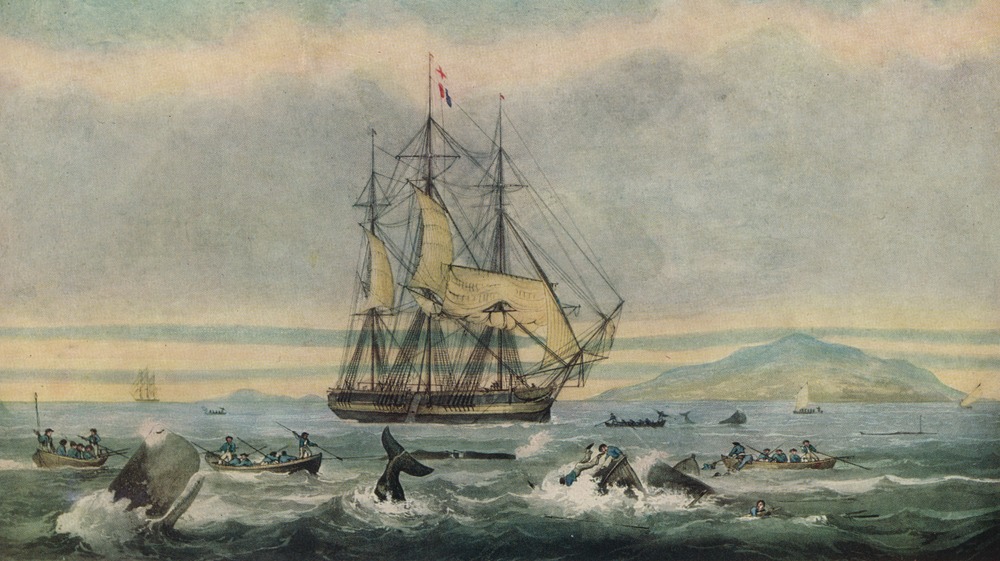

Except we know it can and probably will, because we've seen it happen before with the whaling industry. You might think of whaling as a quaint subject of 19th century novels like Moby Dick, but in reality whaling was a massive industry. It employed tens of thousands, made a lot of people into millionaires, and was one of the most necessary industries in the country's economy.

Times changed. As electricity and cheaper fuel became standard, the difficult work of hunting whales became unprofitable. But for decades whaling ships sailed the seas in search of these immense creatures—and life on board was far from pleasant. If you've ever wondered what it was really like working on a whaling ship, wonder no more.

It was a long and lonely trip

Most people find employment near their home and have a stable routine of commuting or remote work. Even for those of us whose work requires us to spend time in remote locations, we're usually put up in reasonably comfortable accommodations. But if you signed on to work on a whaling ship in the 19th century, you had to be prepared to be away from home for a very, very long time.

As the New Bedford Whaling Museum makes clear, whaling ships had one enormous challenge: Actually locating whales. This took time, and making a trip profitable meant you had to stay out there on the ocean until you found some. Depending on the size of the vessel you signed onto, you could expect to be out for months or even years. In fact, the record for longest single whaling voyage was 11 years. The ship Nile set out in 1858 in search of whales and didn't return until 1869.

It was a lonely existence. Crew sizes varied, but there generally weren't more than 30 or 40 men on board, and sometimes as few as 16. That meant your social options were extremely limited, without much hope of ever meeting any new people. And you could expect to be on the open ocean for months at a time without any contact with other people.

The food on a whaling ship was disgusting

One constant in sea voyages before the modern age is terrible, horrifying food. Before modern preservation techniques, food simply didn't stay fresh for very long. This was a problem for whaling ships that would often be out to sea for weeks or months without access to a port. As History Engine points out, the ships had limited space and limited budgets, with no guarantee of a profit when the trip was finished. That meant having provisions that would last a long time—mainly salted meat, hard biscuits, and lots and lots of beans.

The food was generally tolerable at first, but over time most of it spoiled. Worse, as the New Bedford Whaling Museum points out, it was almost immediately invaded by a wide array of insects and other vermin. Some of the infestations stemmed from the blood and grease embedded in a whaling ship's timbers. No amount of scrubbing could get rid of every trace of a slaughtered whale, and that doomed any effort to keep the ship free of bugs. Simply put, sailors on a whaling ship got very used to eating more than the daily recommended allowance of insects. Considering that some whaling ships stayed out hunting for years at a time, the food was a constant problem for their crews.

There was a rigid hierarchy on a whaling ship

Prior to modern navigational technology and ship building, sailing on the open water was incredibly dangerous. Keeping a 19th-century whaling ship from becoming a floating tomb took a lot of work, and making sure that work was done properly required harsh discipline and a rigid hierarchy.

As the National Park Service notes, that hierarchy divided the ship's crew into specific categories, starting with the captain (sometimes called the master) of the ship. On a well-run whaling ship, the master was an autocrat in total control. Under him were the officers, called mates. The captain and the mates lived better than everyone else, with private or semi-private living spaces and better food.

After that came the boatsteerers and harpooneers, who did the hard work of rowing out and trying to capture whales. Because they were skilled (and crucial to the ship's success) they had more privileges than other crew members. Similarly, professional craftsmen referred to as mechanics (blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, etc.) had it a bit easier.

At the bottom of the ladder were the foremast hands and common crewmen—but at the absolute bottom were the "greenhands," or newbies. Not only did they get the worst treatment and the worst conditions, as the New Bedford Whaling Museum notes they often experienced terrible seasickness, which the veterans openly mocked. In fact, things were so bad for greenhands most of them deserted long before the voyage was over.

The work was brutally hard—when you had work

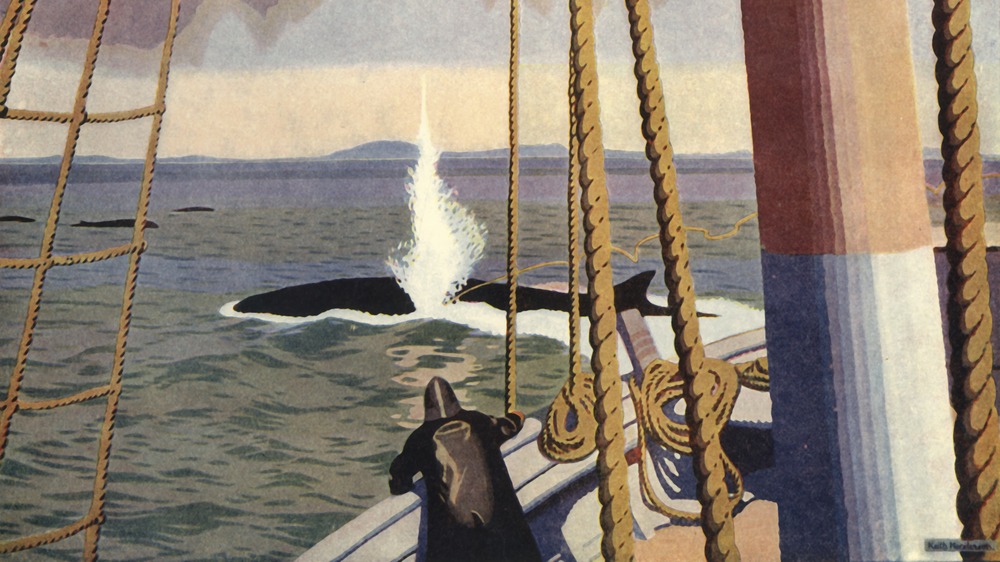

Life as a member of a whaling crew could be really boring because weeks could go by without spotting a whale. But once the hunt was on, the work could be backbreaking.

You might imagine that piling into a boat and chasing after a whale so you could harpoon it might be exciting, and you would be right. But that (often brief) excitement was just a tiny bit of the effort required to transform a living whale into a pile of money. As The National Endowment for the Humanities reports, once the whale was dead, it had to be towed back to the main ship—which by that point might be several miles away. The only way to do it was to lash the whale to your boat and tow it. Since whales can weigh several tons, six men rowing with all their strength might manage one mile an hour.

As Eyewitness to History explains, once the whale had been towed alongside the ship, it had to be "cut in." This involved tying the whale to the side of the ship and butchering the whale on the spot, with just about every hand on board working to reduce the whale to the valuable blubber, oil, and other parts that could be sold for profit. It was hours of hard work that left many blistered and exhausted before it was done.

The pay was abysmal

If people were willing to live under awful conditions and work themselves raw, there must have been a lot of money in whaling. And there was! According to Forbes, New Bedford, Massachusetts (the center of the 19th century whaling industry) had the greatest concentration of wealth in America at the time, all of it stemming from whale oil.

The folks on board the ship doing the work weren't exactly rich, however—and were unlikely to get rich through whaling. As The New Bedford Whaling Museum explains, whaling ships paid the crew through a system of "lays," which were essentially a percentage of the profits. The master of the ship typically got the largest share, about one-eighth of the profits. A "greenhand" or new crew member, however, probably got about 1/350th of the profits—which was sometimes just $25 for several years of work. And of course if they found no whales or couldn't extract enough oil to make the trip profitable, it's entirely possible the crew would get nothing.

Worse, as The National Park Service explains, crew members had to pay for extra provisions from what was essentially a company store on board the ship. An unlucky crew member who had to purchase replacement clothes or other supplies might end up actually owing money to the ship when the trip was done.

Whaling ships were surprisingly diverse

The 19th century (and every century before) wasn't exactly known as a paradise of race relations. It was the century that gave us a literal war over whether or not to get rid of slavery, after all. But whaling ships were floating monuments to diversity and even some equality.

As noted by JSTOR Daily, the multicultural crew described by Herman Melville in his classic novel Moby Dick was a pretty accurate representation of reality. For one thing, Native Americans had been whaling off the coast of America for centuries before Europeans arrived. They made ideal crew members and could be found on most ships of the time. Black Americans and other ethnicities were welcomed on board as well, and many used a whaling trip to earn money to buy their freedom when they returned.

And as The New Bedford Whaling Museum notes, life on board a whaling ship was not only remarkably diverse, it was also much more equitable than on dry land. While racism didn't exactly disappear, crew members enjoyed the same privileges and did the same work no matter their race. Although Blacks often received the lowest pay, in their daily life on board they were largely treated fairly.

There were a surprising number of wives and children on whaling ships

The whaling industry was male-dominated. The crew of a whaling ship was exclusively male throughout most of the industry's history, meaning that anyone who signed on with a whaler might go months or even years without seeing their wife and children, or any other women.

Unless you were the captain or master of the ship, in which case it wasn't all that unusual to bring your family along with you. In fact, it was so common that historian Joan Druett notes the whalers had terms for a ship with a woman on board: "Petticoat Whaler" or "Hen Frigate."

As The Long Island Boating World explains, it was precisely because whaling ships could be out to sea for months or years at a time that many captain's wives chose to travel with their husbands. The alternative was to live alone, sometimes in poverty. According to the National Parks Service, captains who brought their families on board with them had to pay for extra provisions, often to the tune of $1,000 or more, and their wives were expected to work as cooks, nurses, seamstresses, and launderers. For many of the crew, the captain's wife might be the only woman they interacted with for years at a time.

It was incredibly boring

Movies and novels try hard to make the whaling life seem like a great adventure. In many ways it was, of course—you traveled the world, saw incredible things, and learned more about the varying levels of personal hygiene people consider appropriate than you probably ever wanted to. But in most ways, whaling could be incredibly boring.

That's because, as The New Bedford Whaling Museum explains, life on board a whaling ship was actually extremely dull and boring. It wasn't uncommon for whaling ships to go months without seeing a whale—months during which the crew had little beyond routine duties to keep them occupied. While the work of hunting and slaughtering a whale was extremely hard, there was always plenty of downtime in the age before radio, smartphones, and video games.

As the National Parks Service notes, whalers passed this time by playing games and singing, as well as carving scrimshaw from whale bones. There was also plenty of fighting among the crew—exacerbated by alcohol. Historian Joan Druett notes that although liquor was often prohibited, many crews managed to smuggle it on board, leading to plenty of drunken brawls when the boredom and isolation got to be too much.

Whaling was exceptionally disgusting work

If you've read a bit about the whaling life of the past and thought that despite the boredom, low pay, and extreme isolation it still sounds kind of romantic, you might reconsider when you learn just how absolutely gross the work of slaughtering a whale actually is.

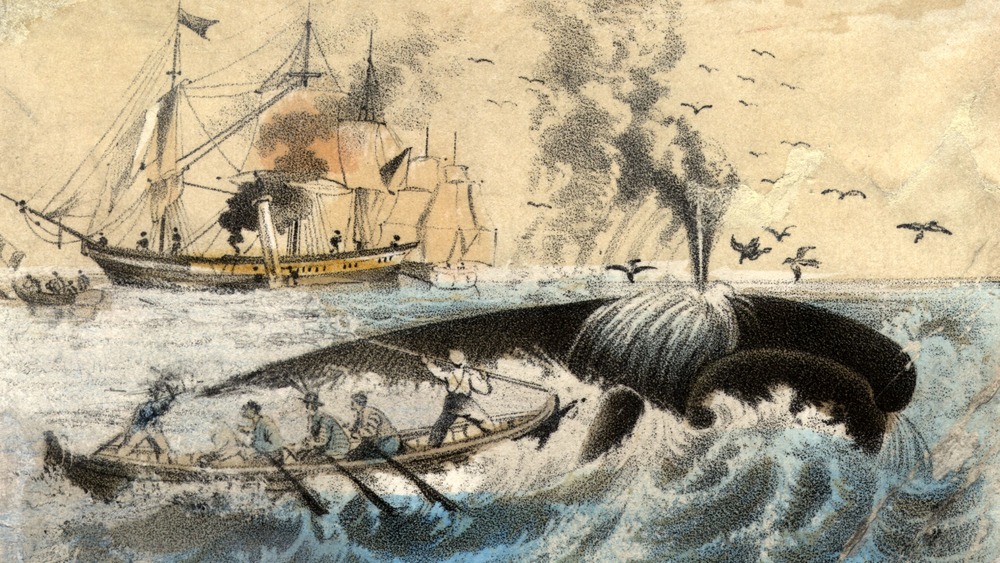

As The National Endowment for the Humanities explains, once the whale had been killed via harpoon and towed laboriously back to the ship, it was lashed to the side and the butchering process began. First, the skin was peeled off in a process called "cutting in"—often in a spiral pattern like peeling an orange. An incision was made, and someone would literally climb onto the whale with a hook and peel the skin away. Meanwhile, it wasn't uncommon for sharks to smell the blood in the water and begin to circle around.

These sections of skin would be cut down and boiled, a process called "trying out." Working in six-hour shifts, the crew would boil the blubber to extract the valuable oil. The process was disgusting. The oil soaked into everything—crewmen tasted it when they ate, and got it on all of their possessions. Blood and grease ran everywhere, and the fires keeping everything on boil billowed black smoke. After all that effort, the ship had to be scoured clean from top to bottom, a process that took several days and never quite stopped insects from swarming.

It was truly dangerous on a whaling ship

Aside from being boring, physically taxing work, the whaling life was also extremely dangerous. In part that's because sailing on the ocean before the modern day was generally dangerous, but whaling brought on extra danger. For one thing, as the National Endowment for the Humanities notes, having a whale carcass in the water often attracted sharks and other predators—and as The New Bedford Whaling Museum makes clear, the process of butchering and rendering the whale left the ship's decks slick with oil and blood—and many men slipped and plunged into the water where they either drowned or were attacked by the prowling sharks.

There are also reports of men being smothered and crushed under huge swaths of whale skin during the butchering process, and of ships catching fire from the boiling process and burning down to the water.

There was also the fact that whales are enormous. They're powerful, dangerous creatures. According to Quartz, it was totally common for whales to destroy whaling ships, with dozens lost over the years to a ramming whale. While scientists don't believe sperm whales to be particularly aggressive, a panicked whale crashing into your ship accidentally will kill you just as well. There just was no shortage of ways to die when whaling.

It was ecologically devastating

If you worked on a whaling ship back in the day, you were basically part of what can only be termed ecological devastation. As The Atlantic reports, whalers in the 19th century killed an incredible number of living things as they rampaged around the Atlantic Ocean. In fact, they killed so many animals scientists think some of our assumptions about extinction and climate change are distorted because we haven't considered just how much killing whaling ships unleashed on the world.

The core reason is food: Whaling ships could only carry so many provisions for their crew, but had to stay out on the water for months, sometimes years. That meant the food stored on board went bad, and ports offering fresh supplies weren't always easy to get to. So the whalers quickly learned that their survival depended on hunting whenever they could—and being willing to eat some surprising things, including barnacles off the bottom of their boats.

Whalers are known to have slaughtered and eaten walruses, kangaroos, reindeer, and even polar bears. Without any way to preserve the meat, that also meant that you lived on a floating slaughterhouse. Everything caught and brought back to the ship had to be butchered, dressed, and consumed very quickly, or it would go to waste.

There were parties on whaling ships

Whaling was a lonely business. Once you signed on you could be sure of spending months or years trapped with a small group of people all day and night. It's easy to imagine how quickly the conversation would run out.

Whaling ships were, however, surprisingly social when the time came—and the time came whenever they encountered each other. As The New Yorker reports, the practice of "gamming" was very common. Unlike commercial ships that were racing to pick up or deliver cargo, whaling ships had nothing to do until they sighted a whale. When they encountered each other, they would often spend days or even a week exchanging gifts, supplies, and crew. Captains' wives would visit each other and host dinners (The New Bedford Whaling Museum notes that a special chair called "gamming chair" was used to lower wives to and from boats), and the crew would cross from ship to ship to find out the news or give each other letters to mail to loved ones and relatives.

In fact, according to the Cold Spring Harbor Whaling Museum, captains would often hold back special food so they could throw fancy dinners when their ship was "gamming."