Creepy Things That Were Considered Normal In Medieval England

The Middle Ages have a reputation as the time in history where nothing much interesting happened. There were some plagues and some Crusades, but beyond that? A lot of mud, some starvation, and... well, these centuries are kind of the historical equivalent of January. The fun's over, the doldrums have set in, and everyone's just kind of waiting for something interesting to happen.

But that's not entirely true. The Middle Ages saw a ton of advancements. Interesting Engineering says that without medieval inventions like the printing press, mechanical clocks, and even eyeglasses, the world today might be a much different place. Even computers have their roots in the Middle Ages, in a super cool gadget called the astrolabe.

Look to medieval England, and you won't just see blokes banging some coconuts together and strange women lying in ponds distributing swords. There was a lot going on, and some of it was super weird. Just like people hundreds of years from now are going to look back at today and wonder what the heck those 21st-century weirdos were thinking, there's a ton of stuff that they thought was perfectly ordinary that looks very strange to us now.

Each bite of bread could have been the end

Bread might seem like the most boring, inoffensive thing on the planet, but throughout the Middle Ages — and across Europe — each bite brought with it the potential for serious illness. The culprit was a fungus called ergot — grains infected with it were unknowingly made into bread, and anyone unfortunate enough to get a loaf would soon descend into what Laphams Quarterly simply explains as madness.

The physical symptoms were easy to see, and the most drastic were arms and legs that would go gangrenous. (National Geographic says the fungus interferes with the body's circulatory system.) But then, there were also hallucinations. A burning sensation led to the disease being called St. Anthony's Fire, and there are stories of entire communities affected by the fungus, with scores of them cutting off their own limbs to try to stop the burning.

And it was very widely known, particularly in damp, cool areas of Europe. Many believed the illness was a sign from the divine — especially because of the whole burning and hellfire thing — and religious orders devoted to St. Anthony set up hospitals to care for the afflicted. A 15th century amulet found in North Lincolnshire suggests (via The Met) that St. Anthony was regularly invoked by people hopeful for his protection... because no one wants to be in so much pain that cutting off their own arms and legs seems like the only solution.

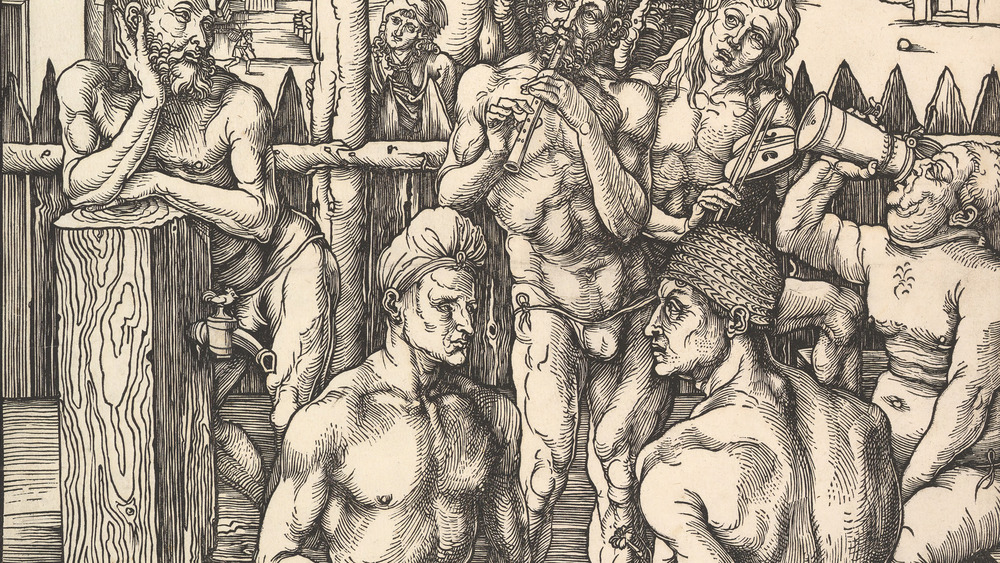

Public hygiene and prostitution went hand-in-hand

There's an oft-repeated rumor that people in the Middle Ages didn't bathe, but that's not true. Historians have found (via Medievalists) scores of medieval texts that refer to the importance of cleanliness — it's next to Godliness, after all, and the people of medieval England were a religious sort. It was widely known how important it was to be clean, but actually taking a bath was complicated.

There weren't many people who had a bath in their own home, so communal baths were a huge deal. In the town of Southwark (on the Thames), there were 18 bathing houses.

And here's where it gets weird. Since bathhouses were co-ed, it wasn't long before they got a reputation as places someone could get a little more than just a bath. Those Southwark bathhouses, for example, became known as the Stews — and they were brothels. It was widely accepted that if you were heading to the bathhouse to get cleaned up after a long day in the fields, you were highly likely to see more than you bargained for.

The Wellcome Collection says the medieval church took a "if you can't beat 'em, join 'em," sort of stance, and by the 15th century the bishop of Winchester was profiting nicely from a series of statutes he had drawn up to oversee the sex workers that were plying their trade at the Southwark stews.

Kicking kids out of the house at what age?

In the 21st century, kids are staying with their parents for much longer than had previously been the norm. On the other hand, let's look at medieval England, through a letter sent from a Venetian who was shocked at what he found in England.

He wrote (via the BBC) that kids were kept in their parents' home "till the age of seven or nine at the utmost," before they were sent "to hard service in the houses of other people, binding them generally for another seven or nine years."

That was across the board, he wrote — rich and poor, boys and girls. Now just imagine waving goodbye to your first-grader and wishing them all the best of luck in life.

Historians suggest that the ages of 7 and 9 weren't absolutes, and many kids ended up staying with their parents until they were somewhere between 10 and 14. That aforementioned Venetian suggested it was because families didn't feel they needed to feed someone else's kid as well as they might want to feed their own. It was also done to give kids the chance to learn a trade beyond what their parents could teach them. Still, given that most kids were illiterate at that age and time, even if they just went to the next town over, it was almost a guarantee they'd have next to no contact with their parents. It was the original distance learning.

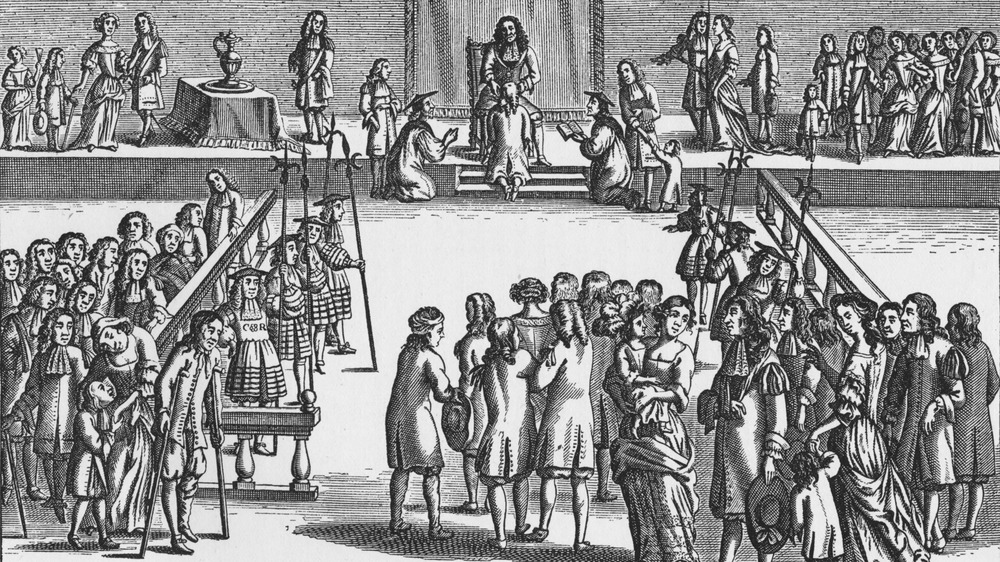

Shaming parades were a thing in medieval England

People always love pointing out the flaws and mistakes of others, and in medieval England, they didn't have social media as a platform for that. Instead, they held shaming parades.

According to Londonist, the idea of public shaming wasn't just popular for hundreds of years, it was pretty creative, too. The specific punishments were often based on the crime — a tavern owner who was found selling bad booze might be forced to drink it before he was paraded through the streets. And then there's the examples that were made of pig thieves. They were escorted through the city with a dead pig hanging from their necks and a crown of pigs' feet on their heads.

The idea of this kind of public shaming went on for centuries and included devices like the pillory (like the one pictured). Use of that particular method of shaming dates back to at least 1318, and it wasn't just a matter of sticking your head and hands through a board and being held there — sometimes, you were nailed there. People absolutely died there — some were pelted with stones, broken glass, and even dead cats, while there's record of others falling through the platform they were standing on and slowly being strangled.

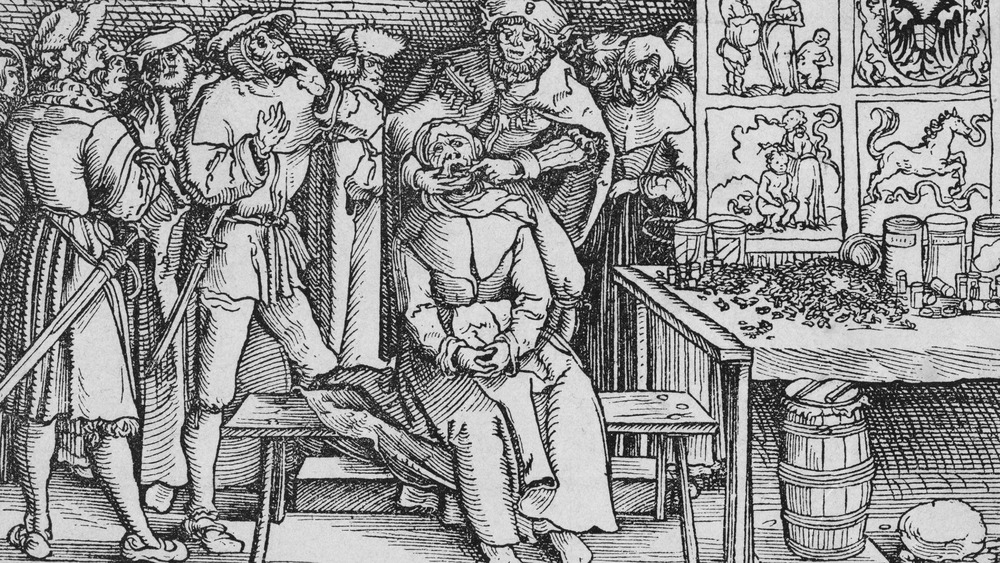

Killing the "tooth worm"

No one likes to go to the dentist, but here's a positive thought — it was even worse in medieval England. Then, anyone going to the dentist risked hearing that they suffered from an infection of tooth worms.

Yes, that's the belief that there were literal worms living inside a tooth and causing it to decay. According to the National Library of Medicine, holes and pits in teeth were thought to be caused by a worm that looked something like a miniature eel. (Different cultures had different tooth worms — others believed it was more like a maggot, and somehow, that's even worse.)

And getting rid of it? Instead of just pulling the tooth, a piece in the British Dental Journal suggests that more holistic remedies were favored, and no, that's not better. One way of getting rid of the worm was to take a candle made from sheep's fat and a mix of seeds and "burn it as near the tooth as possible." The idea was that the worms would run from the heat and fall into a dish of water that was being held beneath the person's mouth. There's no mention of how often that water was used to extinguish the unlucky patient.

An eye for an eye

It might seem like a given that justice in medieval England would have been swift and bloody, but according to research from historians at the University of Leicester and the University of Hertfordshire, that actually wasn't the case... or, at least, that wasn't the intent.

They found that there were things that were greater punishments than, say, losing a hand — things like public humiliation, fines, and being kicked out of a community. When violent punishments happened, the point wasn't to cause the person so much pain that they'd be reformed, it was to mark them in such a way that everyone they met for the rest of their lives would know exactly what they'd done.

In the early medieval period, the payment for many crimes was religious. A person might fast, for example, and it would be up to God to decide if more punishment needed to be delivered via the divine hand of justice. But later on, it became more common to chop off that hand or foot, or just brand a person.

Londonist says the practice of branding — usually on the face — was done into the 1800s, and most of the time, you were branded with a letter that put your crime on full display. If you were convicted of blasphemy, for example, you might be branded with a B. Once that happened, it didn't matter where you went — everyone would know what you'd done.

Come here, my child, and let me poke that

Being a medieval king might seem like it was the best option for making it through the Middle Ages with the minimal amount of muck, but it turns out that it wasn't all fun and games. According to the Royal College of Physicians, some kings were expected to cure an illness called "The King's Evil," and it gets pretty gross.

The whole thing started with England's Edward the Confessor, who was king in the mid-11th century. He became known for touching a person suffering from scrofula — the aforementioned "King's Evil" — and curing them. That wasn't the sort of miracle that anyone was going to let go, so for hundreds of years after, English (and French) monarchs were responsible for touching sick patients and healing them through what was believed to be an incarnation of the divine. Healing events were seriously large-scale, with one court held by Louis XIV reportedly welcoming around 1,600 people to be touched by the king.

Now, it's also worth mentioning exactly what scrofula is... and what the fearless monarchs were touching. Healthline says that scrofula is basically tuberculosis but outside of the lungs. It manifests with lesions and swelling lymph nodes that can grow to a massive size and begin to leak pus, a little tidbit that's necessary to complete the mental picture.

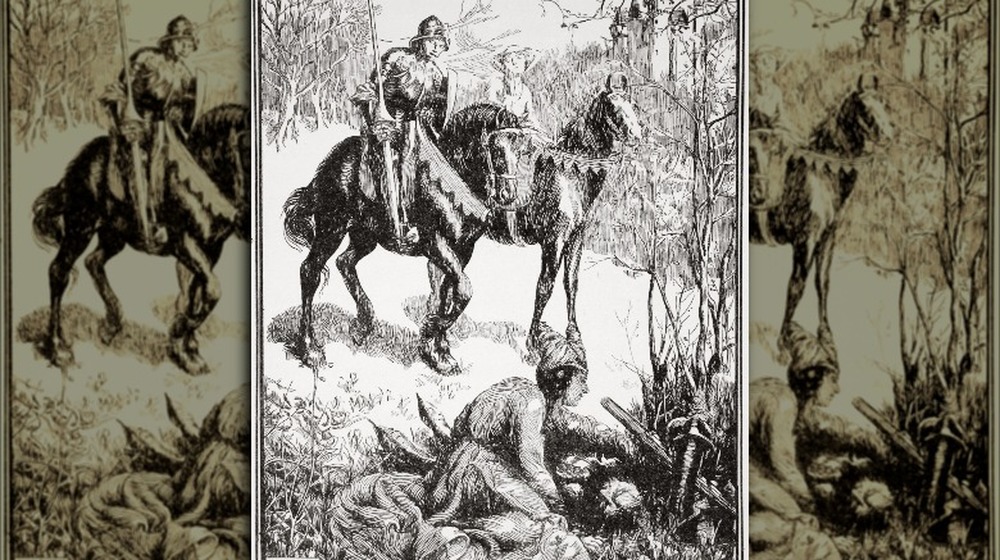

The walking dead of medieval England

The popularity of The Walking Dead helped make zombies mainstream again, and while it seems like it might be something new, it's not — medieval England was believed to be filled with them.

University of Alabama professor of English, Jill Clements, says that it's important to note that in the Middle Ages, people got more up-close-and-personal with the dead and the dying than their 21st-century counterparts ever do. Most people died at home, after all, and it was left up to the family to deal with the remains. It's not entirely surprising, then, to learn that there were a ton of stories about people who believed their loved ones had come back from the dead. While some of the tales are religious or clearly fiction in nature, others aren't.

Belief in the revenant — a reanimated corpse — goes back to the early Middle Ages. One tale comes from the hamlet of Drakelow and was recorded by Geoffrey of Burton (via the University of Manchester). Villagers who were convinced they were being visited by revenants dug up recently buried men and found them suspiciously intact — so, they cut off their heads and put them at their feet, removed their hearts, and reburied them.

How common was that? It's hard to tell, but LiveScience did report that when archaeologists excavated a fourth-century burial ground in Suffolk, 17 of the 52 bodies had been buried after their heads were removed and placed at their feet.

Pee in this cup, I'll tell your fortune

Some things are best left behind closed doors, in the privacy of the bathroom, or at best, just discussed between a person and his physician. In medieval England, that idea definitely didn't extend to urine, and that was because of a widespread, long-held belief that the color, consistency, and taste of a person's urine could be examined to diagnose almost anything that ailed them.

According to Atlas Obscura, the practice of diagnosis-by-urine dates back to at least 100 B.C. That's when it was featured in ancient Sanskrit texts, and it hung around for a shocking amount of time. Fast forward to the late Middle Ages, and it was so common that people were giving the professionals a miss and just self-diagnosing.

According to Medievalists, the very wealthy could even do it with the help of books that printed color illustrations of urine bottles and their corresponding diagnosis. (Which, Atlas Obscura notes, wasn't super accurate anyway, as they hadn't really gotten the whole color printing thing down yet.) Giles Corbeil's 13th century treatise, On Urines, was exactly what the title suggests. What did he teach? The ideal color was white, as it meant all systems were working properly. Wine-colored urine (or blue or black) was definitely really bad... unless a person had been dancing too much, then it was to be expected. And if it's green? Death was knocking on your door.

Are they married?

Every town has that person, the one that has nothing better to do than gossip about what everyone else is doing. Medieval England took that to an entire different level. HistoryExtra says that one of the biggest worries a medieval Londoner might have is whether they're going to heaven or hell (among other things, of course). Rolled into that was the idea that sex was reserved for the institution of marriage, but marriage was a little complicated.

Many times, there was no big ceremony, and there certainly wasn't paperwork and filing with various governments. A couple could be considered married if they — in the privacy of their own home, with no witnesses present — said, "Wanna get married?" and the answer was "Sure!" That's literally all that was required for a marriage to be valid... but proving it valid or invalid in the court of public opinion was something else entirely.

The act of having sex was also considered to make a marriage legal, because marriage and having a wedding were considered two separate things. Marriage was the institution, while the wedding was the big show put on for the benefit of guests. It was also believed that God was the only witness necessary, and considering God is always watching, consent could be made in private. Creepy? Yes, and people absolutely made everyone else's business their own.

You were being judged on your tears

Today, confirms Aeon, crying is strictly something that's reserved for girls. It wasn't always that way, and in medieval England, men and women were both allowed — and expected — to cry freely. The creepy part comes when people judged others on their tears, including the quantity, duration of crying, and frequency.

At the same time tears are recorded as perfectly normal responses to terrible situations, there's another kind of tears — the Gift of Tears. HistoryExtra says this was essentially a sign that someone was thinking of Christ's suffering and became so overcome with emotion that they were moved to tears. These tears were considered a gift from God and set people apart as being particularly devout.

As long as they were correct tears, that is. Cry too often, too loudly, or too much, and people would start to get suspicious that they weren't real, Godly tears after all. Take Margery Kempe, who cried so much that priests would have to shush her during religious services because she'd disrupt them. While some thought she was super holy, others suspected she was actually drunk, ill, or that she was possessed by a demon who was making her appear holy but getting it just a little bit wrong.

The 11th-century St. Peter Damian explained that this fake crying "did not come from heavenly dew, but had gushed forth from the bilge-water of hell." The moral of the story? Be careful how you cry.

Bloodletting and barbers

It's one of those facts that's repeated a lot — barber poles are striped red and white because they used to be doctors. The red is for the blood, the white is for the bandages, and pretty much everyone has heard this by now. There's a little bit more to it.

Hektoen International (A Journal of Medical Humanities) says that for a long time, barbers and surgeons weren't the same thing. In the early Middle Ages, master and apprentice surgeons were even classed and identified separately, which sounds like a very good thing. In the 14th century, barbers were allowed to do things like set broken bones and bandage surface wounds, in addition to cutting hair. The surgeons — the people responsible for operations and amputations — were an entirely different guild. That was true until Henry VIII combined the two in 1540, well after the official end of the Middle Ages.

In the same vein, let's briefly mention one of medieval England's most popular medical treatments — bloodletting. The image of the leech is a famous one, but the creep factor alone makes it worth mentioning that the BC Medical Journal says there were other methods, too. Some tools used scarification, which scraped away patches of the skin, while other lancets were used to slice open veins — including, sometimes, the jugular.