Why No One Lives In These Uninhabited Places

Sometimes, it seems as if our species has fully colonized all of planet Earth, from one pole to another. Sure, a few spots are a little tough to live in fulltime, like Antarctica's McMurdo station or remote islands like Tristan da Cunha, but there are a brave few that live in these places anyway. What can defeat us, after all?

Turns out, quite a lot. Though the worldwide human population now stands at over 7.5 billion (as of 2019), according to the Population Reference Bureau, many of us are packed into urban and suburbans settlements. The United Nations expects that more and more humans will move into cities and towns in the future, leaving rural areas increasingly uninhabited.

Perhaps this helps explain why, despite our ballooning population, there are still quite a few spots on Earth that are practically uninhabited. For one, humans generally appear to enjoy living in groups and in relatively comfortable conditions. Additionally, some regions are simply unacceptable because they're too remote or so inhospitable that only the most extreme organisms can survive for long. Even the most dedicated hermit can't live at the edge of a sulfurous hydrothermal spring.

So, what kind of locations can defeat even our tenacious species? Read on to learn why no one lives in these uninhabited places.

Antarctica's Dry Valleys haven't seen rain for millions of years

Antarctica is so dry that much of the continent is considered a desert, though you'll see neither a cactus nor scorpion there. According to Atlas Obscura, one area, called the McMurdo Dry Valleys, is so named because scientists estimate that it hasn't seen rain or snow in over 2 million years. Not only is it one of the coldest and driest environments on the planet, but it's one of the windiest, too. "Katabatic" winds are sucked down between the mountains, gaining up to 200 miles per hour in speed as they barrel down to the valley floor. Humans do live nearby at McMurdo Station, a research outpost that's home to 1,000 to 5,000 people, yet none will camp long-term in the ultra-intense environment of the Dry Valleys.

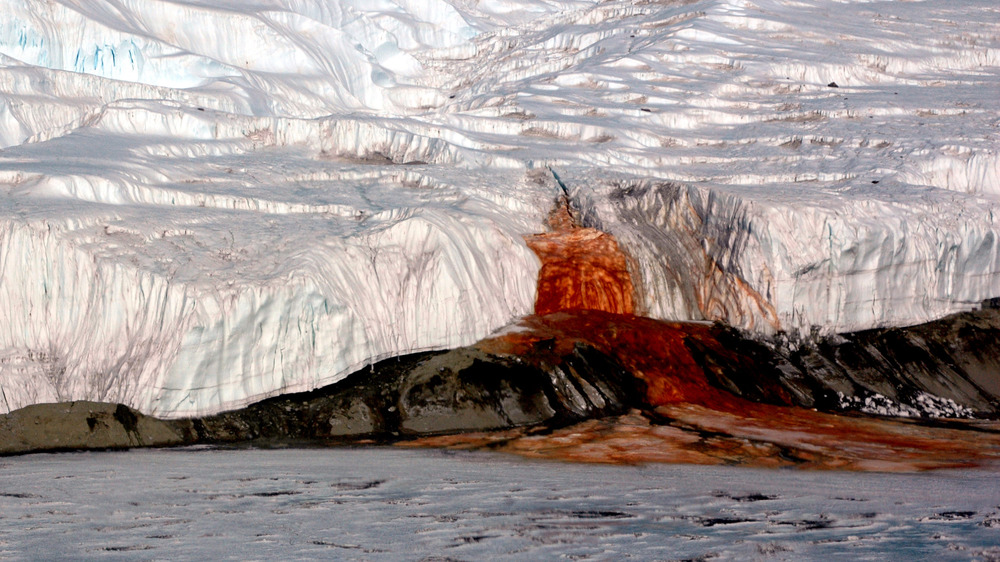

Barren as the valleys may seem, however, life still persists even there. As Atlas Obscura reports, the Dry Valleys are home to the Blood Falls. This feature looks about as ominous as it sounds, for it really does look like bright red blood is slowly leaking out of a feature called Taylor Glacier. Scientists who sampled the ooze reported that it's actually part of an ancient lake sealed beneath the glacier. The slow leak is full of microbes, along with plenty of salt and iron, the last of which lends it that eye-catching color.

The Antipodes Islands prove that not all of New Zealand is good for living

Many people in your life probably want to visit New Zealand, assuming you're not already lucky enough to live there. It's easy to understand why, looking at the gorgeous vistas there. Yet, as beautiful as it may look, not all of this country is picture perfect. In fact, some of it is downright uninhabitable.

As Britannica reports, the Antipodes Islands are about 350 miles south of the country's South Island, making them remote indeed. The islands, which comprise about 24 square miles of land in total, were first recorded in 1800 by British sailors. The islands were once home to fur seals, which have since been hunted almost to oblivion.

Sure, it's remote, but how come no one's trying to live there? These islands are "subantarctic," as New Zealand's Department of Conservation reminds everyone, so the environment isn't exactly easy going. There's also little cover on the land, though the low-lying shrubs and greenery are pretty lush, considering the lack of grazing mammals. The islands have also seen three recorded shipwrecks over the years, with the most recent occurring in 1999 and leading to two deaths. Scientists do occasionally visit for brief periods to study the seabird population and other environmental concerns, but they don't stick around for long and for good reason.

The Danakil Depression in Ethiopia is extraordinarily dangerous

Looking at the Danakil Depression in Ethiopia, you may be briefly tricked into thinking it has a certain kind of harsh, inhospitable beauty. Located largely in the Afar region of northeastern Ethiopia, according to the BBC, the Danakil Depression is full of features like salt pans, hydrothermal features full of colorful bacteria and mineral deposits, and even a rare lava lake. Yet, those features make much of the area intensely uninhabitable, given that it has some of the highest year-round temperatures recorded worldwide and very little rainfall. The highest summer temperatures reach above 130 degrees Fahrenheit.

What's making this region intense and unfriendly to human life? ThoughtCo points to the location of the Danakil Depression, which happens to be situated in a very geologically active area. The depression was formed when three large tectonic plates, or pieces of the Earth's crust, began to pull apart. It's inside a larger rift valley also formed by this massive geologic movement.

People do often visit the area, both to tour the dramatic environment and to farm the rich salt deposits. The hydrothermal hot springs dotting the Danakil Depression are also home to ultra-tough microbes called "extremophiles." This region is also where paleoanthropologists found the remains of a human ancestor known as Australopithecus afarensis, with the individual gaining the popular nickname of "Lucy." Perhaps the Danakil Depression was quite a bit more hospitable millions of years ago, when our early predecessors moved across the land.

Japan's Okunoshima Island is full of rabbits

While some uninhabited places are free of humans because of intense natural environments throwing all sorts of obstacles in the way, other spots are unlivable through our own fault. Such is the case for Okunoshima Island, a small Japanese landmass in an inland sea not far from the city of Hiroshima. Plenty of people visit the place to get closer to the feral rabbits that now populate the island, but these cuddly little mammals are here because of some seriously dark history.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Okunoshima Island was once the site of a World War II-era poison gas factory. It's estimated that the products of these factories killed around 80,000 people during the 1930s and 1940s. The operation was so secret that the Japanese Imperial Army had it removed from all maps.

As The Guardian reports, the rabbits were brought to the island in order to test the efficacy of the poisonous gases. While some sources claim that all the original rabbits were euthanized when the factory ceased production in 1945, others say that the feral rabbits that currently have the run of Okunoshima are the descendants of escapee test subjects. Then again, they might also be the progeny of rabbits who were reportedly released on the island in 1971 by local school children. Either way, with no real predators on the island, the rabbits have been free to multiply as much as the local resources can support them.

Ilha da Queimada Grande is reserved for endangered snakes

Anyone who fears snakes or deadly venom should steer clear of this Brazilian island, though a few lucky herpetologists do get to visit on occasion. According to Atlas Obscura, Ilha da Queimada Grande, also known as "Snake Island," is home to an estimated one to five snakes per square meter. Those snakes are a critically endangered species of pit viper called the golden lancehead, which survives by consuming seabirds that visit the island.

The venom of these vipers is so toxic that very few scientists get the chance to land on the island and study the snakes. Otherwise, all other people are strictly forbidden from setting foot on Ilha da Queimada Grande by the Brazilian Navy. Not that they'd want to be there anyway, given the tales of fishermen and lighthouse keepers who have been killed by the viper's fast-acting venom. Now, reports Smithsonian Magazine, the lighthouse is automated. Any groups that visit the island, whether they are herpetologists or Navy technicians there to check on the lighthouse, are required to have a doctor along with them, just in case.

North Brother Island leaves New York City to the birds

At various points throughout its history, North Brother Island was practically stuffed full of people. Now, though, this small island in New York City's East River is a bird sanctuary that's home only to animals and decrepit ruins. The closest you can officially get to this uninhabited place is via kayak.

Initially, as Atlas Obscura reports, the island was also uninhabited until it was purchased by the city in 1885. That's where officials placed Riverside Hospital, a medical facility meant to keep some of New York's most contagious patients away from the rest of the population. Those ill with diseases like tuberculosis, smallpox, and typhoid were shuttled away from the surrounding boroughs and sequestered on North Brother Island. One of the hospital's most infamous patients was Mary Mallon, better known to history as "Typhoid Mary." As an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid, Mallon was inadvertently making others ill, though she felt fine and vehemently denied that she was a disease vector. Eventually, she was quarantined on North Brother Island from 1915 until her death in 1938.

Riverside Hospital remained open until 1963, when it officially closed and all humans left the island. As per WNYC, all of the buildings are now decrepit shells of their former selves, left rotting in the elements. As the New York City Parks Department urges people to remember, North Brother Island is now best left to the birds.

Mount Everest is way too high

Of course, no one lives on top of Mount Everest. The thought is likely so ridiculous that few amongst us have really considered it, and for good reason. Anyone who sees even a picture from the summit of massive, soaring Himalayan mountains like Everest, K2, or Nanga Parbat can tell that, above a certain elevation, the surroundings become a starkly beautiful but ultimately barren wasteland.

But why, exactly, can no one simply set up a little homestead up there? As the BBC notes, Indigenous people like Nepal's Sherpa have a special genetic adaptation that allows them to thrive in high altitudes, while there are also plenty of animals living in the Himalaya mountains. Yet, even they can only go so far.

LiveScience reports that Everest and other ultra-high mountain environments can induce dangerous altitude sickness. Altitude sickness can begin as low as 8,000 feet but starts to get potentially deadly after 12,000, when the lack of oxygen can cause breathing problems, confusion, loss of consciousness and, in the worst-case scenarios, death. Climbers can acclimate to some high altitudes, but Everest's 29,029 height is nothing to sneeze at.

Then, there are also the dangers of rough, craggy terrain, which can be full of slippery rock and deadly crevasses. Weather in some high-altitude mountains can become deadly in a matter of minutes, with snow obscuring a climber's view while plummeting temperatures put them at risk of hypothermia.

Nunavut's Barren Grounds are all tundra and practically no people

While it's true that very few settlements dot this Canadian territory's land, mostly near waterways, much of it is a wide, uninhabited expanse of tundra.

According to Britannica, most of the Barren Grounds are in Nunavut, though parts of the tundra extend into the nearby Northwest Territories. Most of the land is below 1,000 feet in elevation, but, because of the arctic climate, there are practically no trees in this region. Instead, it's carpeted by low-lying plants such as grasses and lichens, which in turn feed the animals of the region. These include caribou and musk oxen, along with arctic foxes, bears, and the many mosquitoes that swarm in certain areas during the summer thaw.

The region is also packed full of rivers, creeks, and lakes. As NASA reports, these and other wetland areas help to make the so-called "Barren Lands" a unique and, for some species, rich environment in which to live. The humans who do live in the region are few and far between, with most being Inuit settlers along the coast. For the wildlife that ventures into the interior, that scattered human population probably suits them just fine.

Palmyra Atoll is a nature reserve and a crime scene

Palmyra Atoll was once inhabited, though the human presence proved to be nearly disastrous for the island's small ecosystem. According to The Nature Conservancy, a lush rainforest once covered the atoll, but a combination of United States military presence, coconut farming, and a rat infestation have reduced the forest's footprint. However, the conservancy is working to restore the rainforest, helped along by the atoll's location in a protected wildlife reserve.

Admittedly, some people do stay on Palmyra Atoll for short periods of time. As NPR reports, the Nature Conservancy bought the atoll in 2000, turning it into a nature sanctuary and research station. Scientists and staff use basic cabins, shared toilets, and a lab. However, no one's allowed to live there full-time or build much beyond what's already there.

The atoll was also the site of a notorious murder in 1974, after the military presence had left the island but before it became a research station. As per The San Diego Union-Tribune, the two victims were Eleanor "Muff" Graham and her husband, Malcolm Graham. The couple disappeared in August 1974. An ex-con and his girlfriend were accused of stealing the Grahams' sailboat, the Sea Wind. When a different sailor stumbled across Muff's bones on the beach at Palmyra Atoll in 1981, the thieves were saddled with murder charges. They had apparently come across the Grahams at the atoll and, seeing an opportunity, killed the two and took their boat.

Hashima Island is a haunting ghost city

Once a bustling offshore mining facility near Nagasaki, Japan, Hashima Island is now home only to a deteriorating abandoned city. Many may have already seen it in the 2012 Bond film Skyfall, according to Wired, but the true story of the place is far more complicated than the island being only an atmospheric villain's lair.

The 16-acre island was once a major coal mining facility for Japan and was inhabited from the late 19th century until 1974, when everyone abruptly left the place, also known as "Battleship Island" for its shiplike shape. Because it was such an important resource, the Mitsubishi corporation built a densely packed settlement on the island, including tall apartment buildings, schools, and a hospital. When the coal ran out, however, there was no reason for anyone to stay. The departing masses, which once reached around 5,000 people in the 1950s, left their city behind to rot.

Since then, the structures on Hashima Island have been battered by the combined forces of the saltwater-laden air, the waves, and occasional typhoons. National Geographic reports that scientists are now attempting to save the steel-reinforced concrete buildings for their historic value. Until then, however, no one lives there, and few dare or get permission to land on the island and walk amongst the dangerously crumbling ruins.

Iceland's highlands are more intense than you think

Though Iceland is a popular tourist destination, most visitors and locals stick to cities and towns along the coastline of this Atlantic island. Some may venture into the interior of Iceland for day trips to view some of the nation's stunning vistas or natural wonders like waterfalls and geothermal pools, but not all of the region is quite so hospitable. The highlands of Iceland are so intense that it's practically uninhabitable.

According to Guide to Iceland, the highlands take up the majority of the country. They're full of snow and glaciers, as well as volcanos like the infamous Eyjafjallajökull, whose 2010 eruption choked the skies over Europe with volcanic ash and grounded many flights. In the east, wild reindeer are sometimes spotted, along with the occasional vehicle of tourists, so long as the intense snows haven't closed the paths crossing the highlands.

Beautiful as the place may be, Iceland: The Bradt Travel Guide stresses that pretty much no one wants to live there. In some places, snow can fall quickly and heavily, so much so that intrepid early settlers were turned back to safer homes along the coast. In other places, it's so dry that there simply isn't enough water to sustain people. Between the weather, the intense cold, the fast-moving winds, and the volcanoes spewing potentially deadly gas and lava, it's no wonder that most people would rather live more comfortably in a modern settlement down near the ocean.

No one can visit Nomans Land because of all the bombs

Upon first glance, Nomans Land seems to be a perfectly nice little island some three miles from Martha's Vineyard in Massachusetts. Anyone trying to get to this admittedly ominous-sounding place will either be turned back pretty harshly by the military or else face a far worse surprise.

That's because, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Nomans Land Island is full of bombs. Specifically, the 628-acre island is littered with unexploded ordnance, left over from the days when the U.S. Navy used the area as a training ground for service members in 1970. The Navy handed it over to the FWS in 1998, where it's since been designated as a National Wildlife Refuge.

Nomans Land remains pretty tempting for some, thanks to a colorful legend involving Vikings and a mysterious rock. Said rock is known as a runestone and, if proponents of the story are right, it's evidence that the Norse people visited more of North America than previously thought. According to Atlas Obscura, the "runestone" was first spotted in 1926, when an unusually low tide revealed a rock that was supposedly covered in odd but intentional markings. No one's been able to confirm the legend yet, though the dangerous area of Nomans Land, including the rocky shore and sometimes high waves, have hampered many explorers' efforts.