We Still Don't Know The Secrets Of The Antonio Stradivari's Violins

For a professional violinist playing a "Strad" or Stradivarius instrument is an almost-impossible dream and a pinnacle of their musical career when, and if, the time arrives. A kind of mystique resides around these instruments, classical music's form of the holy grail.

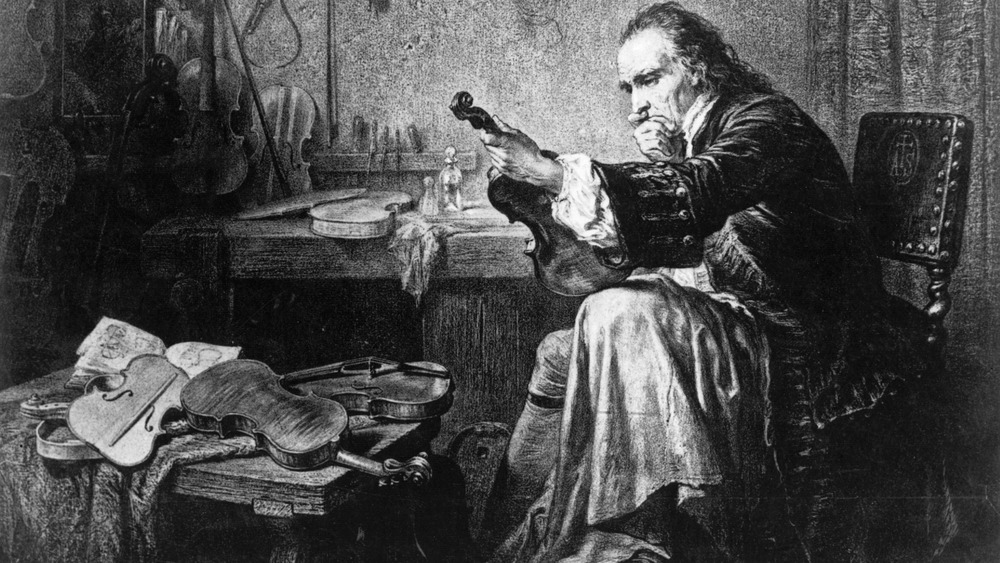

Luthier Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) made about 1,100 string instruments in the late-1600s to the mid-1700s — an assortment of violins, cellos and violas, many that now sell for six figures, according to CNN. For example, the Molitor Stradivarius, that allegedly once belonged to Napoleon, sold for $3.6 million in 2010, and the Lady Blunt Strad went for $15.9 million in an auction the year after, per eXtravaganzi. The price for Stradivari's work only seems to rise each year.

Most treasured of Stradivari's work seems to be the 550 remaining violins — whittled down over the years from about 960. "Stradivari got it right," said Tim Ingles, co-founder of the fine instrument specialists firm, Ingles & Hayday, to CNN. "The balance between hard and soft (wood), so the box can vibrate ... He never makes the same violin twice, always trying to improve the sound and look."

For years, scientists and others have strived to find the Stradivarius' secret to music making. One theory states that the 17th century experienced less solar activity and had "colder winters and cooler summers" that "produced slower tree growth which in turn led to a denser wood with superior acoustical properties — circumstances not repeated since," said the BBC.

Theories about Stradivari's violins

Others believe that the type of wood makes the difference, or even the varnish. In fact, Stradivari's formula for this isn't known — another part of the mystery. It is often thought that the secret of his instruments lies in a combination of factors including the thickness of the wood he used, the microscopic pores within that material, as well as the varnish.

But many violin makers attribute Stradivari's skill over the materials used. The instruments that Stradivari made signaled a change in performance space. While previously smaller gatherings in private homes and other places were popular, Stradivari's creations were used in bigger venues such as concert halls. "Stradivari came through, he proved a match for the new music being made," the BBC quoted Dr. Jon Whiteley, a curator at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. "All his life he was searching for the ideal shape."

The craftsman never stopped experimenting to make a better sounding instrument. Stradivari learned his craft from Italian violin maker Nicolo Amati as an apprentice and began making some under his own name in 1666. He initially copied what he had learned, but by 1684, Stradivari started altering many commonplace techniques of the time period, including the type of varnish he applied. "The Stradivari method of violin making created a standard for subsequent times," according to Britannica. "He devised the modern form of the violin bridge and set the proportions of the modern violin, with its shallower body that yields a more powerful and penetrating tone than earlier violins."

Real or not real? A Strad problem

His sons, Francesco and Omobono, became instrument craftsmen as well. It is thought they probably worked alongside their famous father at some point but never reached his accomplishment.

Stradivari's most productive work, known as his gold period, occurred from 1700 to 1725. His workshop resided in Cremona, Italy, his birthplace. Besides the ones the master created, many craftsman copied his techniques and used a Stradivari label, so as Smithsonian points out, the presence of one does not mean its an actual Strad. "Affixing a label with the master's name was not intended to deceive the purchaser but rather to indicate the model around which an instrument was designed," stated the organization. "As people rediscover these instruments today, the knowledge of where they came from is lost and the labels can be misleading."

Telling a fake from a real Strad needs expertise, according to The Globe and Mail. An experienced person, "who has examined thousands of violins, will look at the design, wood, varnish and every other part of the violin. For instance the pins Stradivari used to fit the back into the rest of the violin are very distinct."

If you're yearning to try playing a Stradivarius, it's not going to be easy. The remaining instruments are rare and hard to find. Even famous musicians sometimes need a rich benefactor to get access to one.