Tragic Details About Red Cloud

During his life, Red Cloud, also known as Maȟpíya Lúta, was a household name. Almost everyone in the country knew of the Native American's resistance against the expansionism of the white man, but by the end of his life Lúta feared for what was going to happen. Lúta played an incredibly critical role in resisting white expansionism. The Second Treaty of Fort Laramie is especially notable for being one of the few instances when the United States was forced to remove their soldiers from Native land, but inevitably most of this ended up being a delay rather than a cessation.

Throughout his life, Lúta continued to campaign to improve the lives of Native people in the United States. Lúta continued visiting Washington, D.C., until his final visit in 1897. During one visit in 1889, he said "When I fought the whites I fought with all my might. When I signed a treaty of peace I meant to do right, and I have often risked my life to keep the covenant."

Unfortunately, Lúta was unable to keep white invaders out of his land no matter how many treaties they signed. While he kept his promises, he spent his life watching the United States break theirs. These are some tragic details about Red Cloud.

Red Cloud's early life

Maȟpíya Lúta, also known as Red Cloud, was born around May 1821, near where the North and South Platte Rivers unite in what was considered Nebraska Territory. His father was a Brulé Lakota and his mother was an Oglala Lakota, and together they belonged to a subdivision of the Oglala known as the Bad Face band.

There are conflicting accounts about Lúta's early life. According to Red Cloud: Photographs of a Lakota Chief, Lúta's father died of alcoholism when Lúta was young, and as a result, he was brought up by his mother's brother Šóta, also known as Old Chief Smoke. But according to "Red Cloud, as Remembered by Ohiyesa," Lúta's father survived until Lúta was 28 and died during a disagreement with Bear Bull, an Oglala leader.

However, one of the earliest events in Lúta's life is relatively well-documented. According to the Autobiography of Red Cloud by Red Cloud, Charles Wesley Allen, and Sam Deon, when Lúta was 16 he joined a raid party against the Pawnee, who had recently slain his cousin. The raid was successful, and Lúta had soon made a name for himself after another successful ambush against the Crows. By 1850, Lúta had married Pretty Owl, also known as Mary Good Road, and they remained together until his death in 1909. She later died in 1940 at the assumed age of 104.

The United States finds gold

Before the 1860s, the Sioux had relatively few contacts with white people. But once gold was discovered on their land, white people started flocking across the country. According to Representative Americans: The Civil War Generation, the South Platte River valley had seen an earlier gold rush in 1859, and once gold was found in Montana in 1862, the Bozeman Trail was promptly established.

According to Northern Plains Reservation Aid, the Bozeman Trail was a pre-established trail that had been used for thousands of years by different Native groups in North America. Such roads were incredibly common across the North American landscape prior to colonization, and according to An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States, "many have noted that had North America been a wilderness, undeveloped, without roads, and uncultivated, it might still be so, for the European colonists could not have survived." The Bozeman Trail also connected with the Oregon Trail, bringing "miners, immigrants, settlers, and wagon trains directly through the buffalo feeding areas."

As white settlers started moving down the trail, forts were built along the Bozeman Trail by the U.S. Army to protect the settlers, with little concern for the fact that the trail "passed through territory inhabited by the Shoshone, Arapaho, and Lakota nations." And since the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty had established Powder River county as hunting land for the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Oglala and Brulé Sioux, the Bozeman Trail was a clear treaty violation.

Red Cloud's War

In 1865, Lúta began leading a series of attacks against the white men on the Bozeman Trail that lasted until 1868. Known as Red Cloud's War, Lúta united the Lakota Sioux, Northern Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne against white settlers, miners, and soldiers.

During the war, the U.S. Army suffered one of their biggest military disasters at the time during the Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands on December 21, 1866 after Captain William Fetterman had "boasted" that he could easily pass through the Sioux Nation with as many men as he had. According to Imperialism and Expansionism in American History, 81 American soldiers were killed and this massacre led the United States government to invite Lúta "along with 125 other chiefs, to discuss terms."

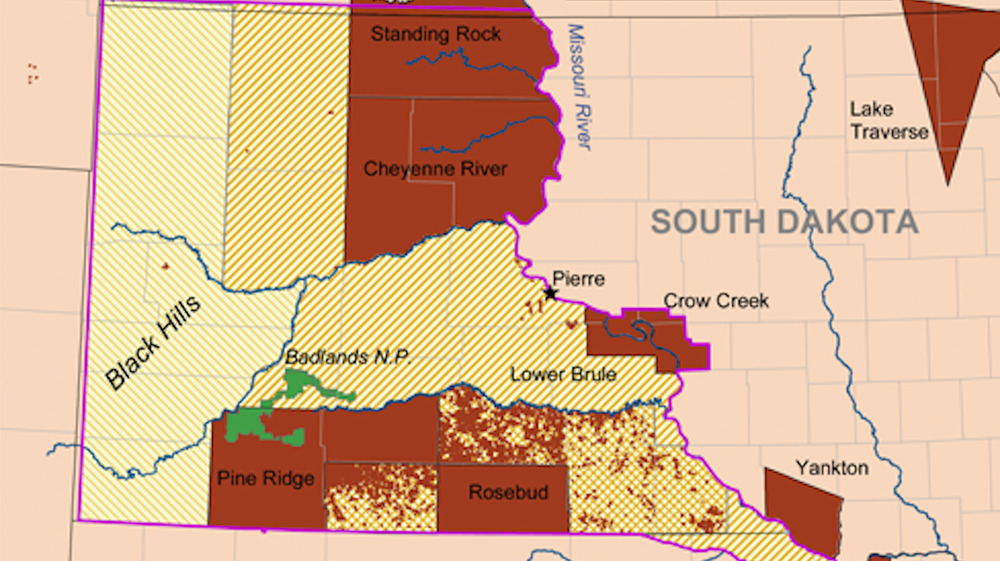

The negotiations lasted for two years, and according to Biography, at one point Lúta simply stormed out. But in the end Lúta was able to "force the U.S. Army to abandon several forts on the Bozeman Trail" during the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, per A Whirlwind Passed Through Our Country. The treaty also established the Great Sioux Reservation and gave the Lakota possession over the western half of South Dakota, as well as parts of Wyoming and Montana territory. However, it wasn't long before the United States government started picking at the border lines of the reservation.

Trying to find a middle path

Lúta spent the 1870s and 80s trying to mediate relations between the Sioux and the United States and after the treaty negotiations continued to act as a diplomat for the Oglala Lakotas. According to Heritage History, in 1870, he traveled to meet with President Ulysses S. Grant in Washington, D.C., which led to the establishment of the Red Cloud Agency, a reservation in Nebraska territory for his tribe. However, it wasn't long before the United States government moved the Oglala Lakota while simultaneously carving up the Great Sioux Reservation.

According to Northern Plains Reservation Aid, Lúta was accused of colluding with the United States by younger Oglala while he was simultaneously accused of duplicity by the federal government. After General Custer found gold in the Black Hills in 1874, miners started flooding into Sioux territory once more. In 1875, Lúta traveled to Washington, D.C. with other Native leaders once again to request that the existing treaties be honored, but Congress tried negotiating a relocation of the Sioux instead.

The Lakota leaders, including Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (Sitting Bull) and Tȟašúŋke Witkó (Crazy Horse), refused this new arrangement, which led to the Great Sioux War of 1876, although Lúta was notably absent from the war. Despite this, the American government accused him of helping the group that overwhelmed General Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn. And because of his absence, many Oglala considered him a traitor.

Chipping away at the reservation

After being established in 1871, the Red Cloud Agency was moved four times before the end of the decade. In its final move in 1878, it was relocated and renamed as the Pine Ridge Reservation within the Great Sioux Reservation. According to The Last Days of the Sioux Nation, the Spotted Tail Agency was also relocated out of Nebraska territory and moved into the designations of the Great Sioux Reservation.

Meanwhile, the United States government was busy chipping away at Native land across the country. According to Imperialism and Expansionism in American History, the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 partitioned off land to individual tribal members, while the Sioux Bill of 1889 carved the reservation into smaller pieces and allowed white people to claim the rest of it, roughly nine million acres of land. In comparison, the original reservation had been almost 20 million acres.

The loss of the Black Hills in 1876 was also immeasurable, and continues to be a point of contention between the Sioux and the United States government to this day. In the 1980s, the Supreme Court offered over $100 million to the Sioux as compensation for the Black Hills, but the Sioux refused the money, stated that "the payment is invalid because the land was never for sale and accepting the funds would be tantamount to a sales transaction," as reported by PBS. The settlement remains in a trust and is now valued at over $1 billion.

Visit with Othniel C. Marsh

On the reservation, Lúta quickly found that the promises made by the United States government were hollow and he ended up recruiting the most unlikely ally. According to Red Cloud and the Sioux Problem, in 1874, Lúta had made the acquaintance of Othniel C. Marsh, a notorious fossil hunter, who was excavating in the Dakota badlands. Marsh had to persuade Lúta that he was looking for fossils and not gold, and in the end Lúta was surprised at Marsh's honesty.

Lúta gave Marsh some coffee, tobacco, sugar, and flour to show the abysmal quality of rations that were being distributed by the United States government, which led Marsh to file a complaint with the Board of Indian Commissioners in addition to making a public statement about how the Sioux were being treated. In 1883, Lúta paid Marsh a visit in New Haven, Connecticut, and there's even a record of the two of them having kept up a correspondence. It's said that Lúta referred to Marsh as "Big Bone Chief."

Although it's claimed that Lúta later stated that the samples he gave Marsh weren't representative, the investigation did actually lead the government into changing their contractors for flour and pork. They also replaced Dr. John J. Saville, the reservation agent at the time, although the next one didn't seem to be any better.

Red Cloud and Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy

On the reservation, Lúta also found himself in constant conflict with Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy, the white man assigned as the reservation agent for the Oglala Lakota in the 1880s. According to "Federal Children: Indian Education and the Red Cloud-McGillycuddy Conflict," the clash between Lúta and McGillycuddy was demonstrative of the larger battle over assimilation waged by the United States government against Native people. McGillycuddy saw himself as a "civilizer" and as he sought to expand his own influence he hoped to diminish Lúta's.

In 1880, McGillycuddy gathered a council of Sioux together in 1880 and demanded that they renounce Lúta as their leader as he sought to undermine Lúta's authority. McGillycuddy maligned Lúta to everyone, accusing him of being "an enemy of both the government and the progress of his people."

At the same time, Lúta was repeatedly criticizing McGillycuddy over his mismanagement of government supplies and food meant for the reservation. And according to The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee, other grievances included threats of withholding rations and suppression of the Sun Dance. Many of these accusations would turn out to be true, but investigations always ended up asserting McGillycuddy's innocence. By the end of his tenure, much of McGillycuddy's ire was directed at Red Cloud's resistance to the boarding schools that Native children were being sent to.

During the Ghost Dances

During the Ghost Dances of 1890 to 1891, Lúta was once more accused of seeking to undermine the authority of the United States of America. As dozens of Lakota set out and "danced to hasten the coming of the new world," even though Lúta himself did not participate in the ghost dance, "many whites accused [Lúta and Íyotake] of being leaders of the ghost dance and instigators of trouble."

According to "When the Spirits Arrived: Divergent Lakota Voices of the 1890 Ghost Dance," although Lúta's son was an active dancer and he didn't stop his people from dancing, in a letter to Thomas A. Bland of the National Indian Defense Association, Lúta derided the Ghost Dance. On December 10th, 1890, Lúta wrote "I haven't been to see the dancing. I will try to stop it. Those Indians are fools. The winter weather will stop it, I think. Anyway, it will be over by spring. I don't think there will be any trouble. They say that I have been in the dance. That is not right. I have never seen it."

In the end, Andersson suspects that Lúta's decision to avoid and dispel the ghost dance was likely a political decision rather than a religious one. Lúta knew of the United States' tendency to escalate situations, and unfortunately the Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29th, 1890 brought his worst fears to life.

The end of Red Cloud's life

During the final years of his life, Lúta took on the name "John" and converted to Christianity. Having become blind by the end of his life, his wife Pretty Owl assisted him until Lúta died at the age of 88 at Pine Ridge Reservation on December 10th, 1909. And the cemetery he was buried in was named after him. According to Biography, Lúta "ended up outliving all the major Sioux leaders" who were part of the "Indian Wars." However, by the end of his life Lúta had lost much of his influence, especially after McGillycuddy was successful in having him deposed as leader.

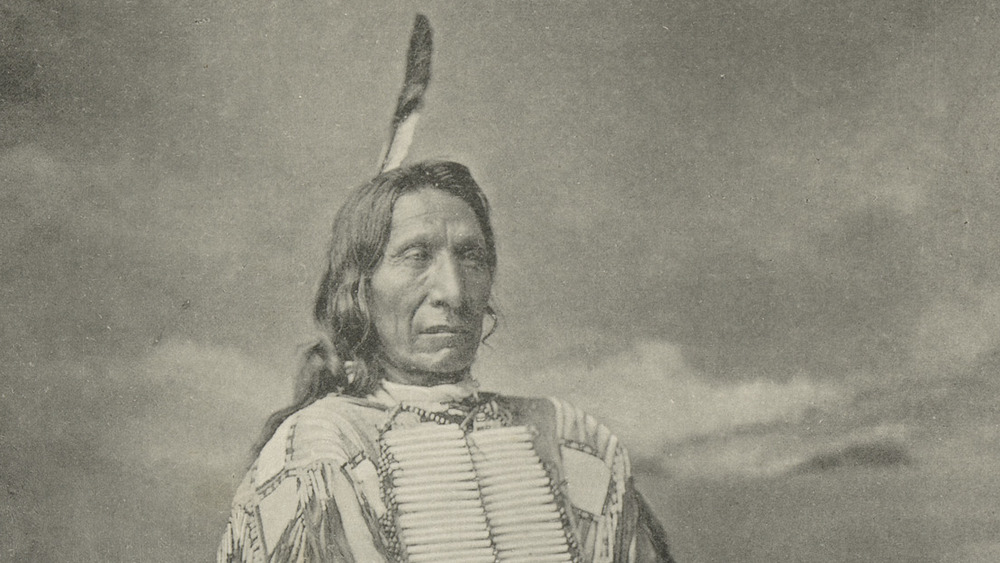

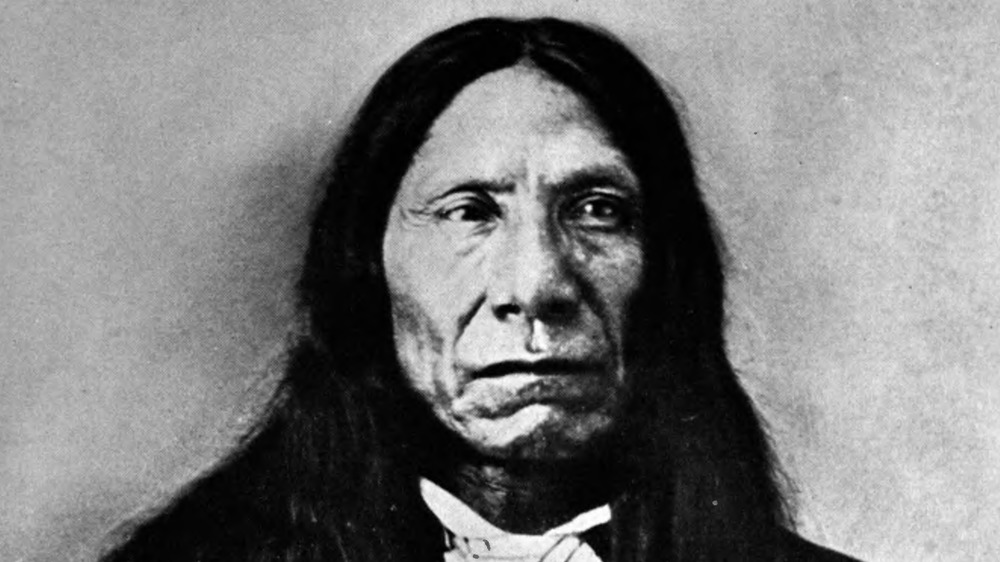

According to The Sioux: The Dakota and Lakota Nations, during his life Lúta ended up becoming the most photographed Native person in United States history. He posed in dozens of photos, sometimes dressed in his normal clothing, and other times wearing the costume of the colonizer. Overall, there are at least 128 known photographs of Lúta.

The book Red Cloud: Photographs of a Lakota Chief notes that "Between his first trip to the East in 1870 and his death in 1909, photography gave Red Cloud a tool with which to mark his presence and to negotiate relationships with others." However, ultimately it remains impossible to know what his motivations were when it comes to his photographic engagement.

The legacy of Red Cloud

Before Lúta died, he was visited by an anthropologist. Lúta lamented to him about the poor state of affairs. Even though the government had promised to provide food for Native people, they were forced to beg in order to receive anything. Meanwhile, the land they had been moved to was barren and Lúta reminisced about the "rich soil in a well-watered country" that he used to possess. At one point, Lúta said to the anthropologist, "I wish there was someone to help my poor people when I am gone."

Unfortunately, this acclaim does little to remedy the situation of his descendants while the United States government continues to try to claim their land.

Starting in 2016, the Lakota Oyate and the Dakota Oyate of the Standing Rock Reservation began protesting the construction of an oil pipeline and many claimed that the pipeline was a treaty violation if it passed through Native land, in addition to citing the various health risks associated with living near the pipeline. In March 2020, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe won a victory in federal court that would require a new environmental review of the Dakota Access Pipeline. However, the future of the Standing Rock Tribe and the Dakota Access Pipeline remains uncertain.