Why The Halifax Explosion Was One Of History's Biggest Tragedies

Despite being one of the most tragic and devastating man-made disasters in North American history, the Halifax Explosion remains largely unknown. On Dec. 6, 1917, the collision of a Norwegian supply ship with a French freighter hauling high explosives in the narrow waterway between Halifax, Nova Scotia's Bedford Basin and the Atlantic resulted in an explosion unprecedented until the detonation of the atomic bomb that devastated Hiroshima at the close of World War II.

Thousands were killed and injured in the initial blast, and more would lose their lives in the ensuing fires and tsunami created by the explosion's shockwave. Yet, the scope of the tragedy would expand far beyond that dreadful day in December as a sudden blizzard hampered rescue and relief efforts. Perhaps most tragically, the specters of racism and intolerance would leave many victims uncounted and uncared for.

Beyond the incalculable cost in human life, the psychological toll the Halifax Explosion inflicted on Nova Scotians resounded for generations. Halifax would rebuild but never fully escape the tragedy of the disaster. As author Sally M. Walker wrote in her 2011 history of the explosion, Blizzard of Glass, "Old scars are hidden by sturdy stone houses, and tall trees line remade streets. But the roots of the story are still there, and they grow deep."

What follows are the details of a day marked by untold sorrow and acts that both exalt and diminish the character of the human spirit. This is the tragic real-life story of the Halifax Explosion.

Halifax and the First World War

The capital of Canada's eastern province of Nova Scotia, Halifax has long been an important hub for commerce and industry. Located on the Atlantic coast, Halifax Harbor, flanked on the west by the cities of Halifax and Dartmouth, is traditionally an essential trade and logistics port in times of war.

Despite its strategic and economic import, the area had fallen on hard times in the early years of the 20th century. However, with the outbreak of World War I, the strategic port made a stunning economic comeback. From the earliest days of European settlement through the American Revolution and The War of 1812, conflict had often proved a financial boon for Halifax. As detailed by Laura M. McDonald in Curse of the Narrows: The Halifax Explosion of 1917, harbor traffic swelled from 2 million to 17 million tons per year with the advent of the conflict in Europe.

With the United States' 1917 entry into the war, the essential Canadian port became a potential target for Germany's U boats. Patrol ships and anti-submarine nets were quickly put in place to protect the humanitarian supplies and munitions that steadily departed Halifax Harbor for Europe. In addition to man-made defenses, a slim passage between the harbor's Eastern Passage and its expansive Bedford Basin would serve as a choke point for any hostile vessels. Ironically, all of these elements served to exacerbate the circumstances that would lead to one of the greatest maritime disasters in history.

The Imo and the Mont-Blanc

Originally launched as the SS Runic by Great Britain's White Star Line, the shipping firm best known today for launching the ill-fated RMS Titanic in 1912, the SS Imo was a whaling supply ship operated by the Southern Pacific Whaling Company. The ship, ported in Norway, had been chartered by the Belgian Relief Commission, a private charity organization dedicated to getting food and humanitarian aid to war-ravaged Europe. As documented in Curse of the Narrows, the Belgian Relief Commission raised over a billion dollars from donors worldwide. As a neutral agency, ships sailing under the auspices of the charity could traverse the Atlantic without fear of harassment by either British or German forces. However, this changed with Germany's 1917 declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare. Crews of ships such as the Imo frequently faced sinking or the capture of their cargoes.

Laden with picric acid (an extremely volatile chemical explosive used in artillery shells), nitrocellulose (a propellent used in munitions also known as guncotton), TNT, and barrels of benzole ship fuel, the freighter Mont-Blanc was a literal floating powder keg. On Dec. 6, 1917, the ship was en route from New York and scheduled to join a convoy at Halifax for the long, treacherous journey across the Atlantic. To avoid being targeted by enemy ships, the Mont-Blanc took advantage of the wartime suspension of flying a red flag to alert sea traffic of the explosives in its hold.

The collision in Halifax Harbor

As recounted in Laura McDonald's The Curse of the Narrows, a simple breach of maritime etiquette led to the collision that sparked the Halifax Explosion. On the morning of Dec. 6, 1917, the American tramp steamer SS Clara cleared the submarine nets and entered the harbor on the Halifax side just as the Imo was approaching. The Clara sounded a single blast from its whistle announcing its intention to cross on the starboard side despite regulations that ships pass only port to port. The Imo, already sailing a day late due to a fueling delay, accommodated the smaller ship. Following harbor regulations would require a time consuming maneuver, and the empty relief ship was past due to pick up its cargo in New York. Unbeknownst to the Imo's crew, their craft, now entering the Narrows on the wrong side, was on a collision course with the explosives-laden Mont-Blanc.

As the Imo entered the Narrows, Francis Mackey, pilot of the Mont-Blanc, spotted the Belgian relief ship. Judging by foam at its bow, it was cruising at a high rate of speed for the small waterway.

Fearing that grounding the ship would detonate its volatile cargo, Mackey steered the Mont-Blanc hard to port. Within a ship's length, the Imo killed its engines. The Mont-Blanc sounded its whistle three times as Mackey reversed the munitions ship's course. Nevertheless, the efforts of both crews were in vain. Under momentum, the Imo cut through the Mont-Blanc's hull.

An explosion of incredible magnitude

Laura McDonald writes that the crew of the Mont-Blanc was initially relieved following the collision. Although the ship was badly damaged, the ship's TNT-packed number one hold was intact. However, the crew's relief turned to dreadful realization as the Imo reversed its engines to free its bow from the Mont-Blanc's hulls. As the ships separated, barrels of highly flammable benzole overturned, flooding the Mont-Blanc's deck. Sparks flew from the grinding steel bulkheads igniting the spilled fuel. Soon, the French munitions vessel was a floating inferno.

As recounted by History.com, the burning Mont-Blanc, pushed shoreward by the collision, ignited a harbor pier. Meanwhile, onlookers lined the shores of both Halifax and Dartmouth to watch the fiery spectacle. Suddenly, a blinding flash of white light lit up the morning sky.

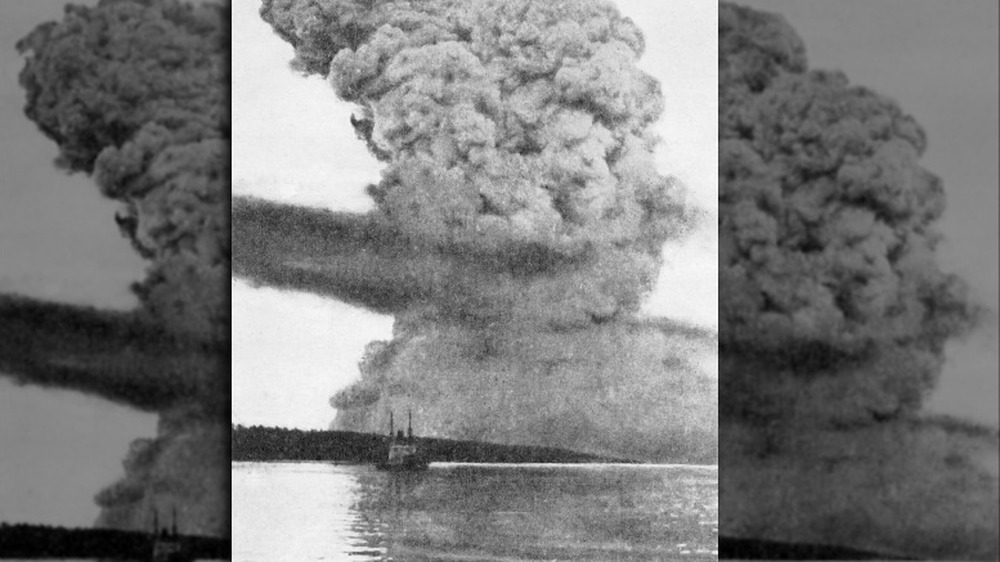

According to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, the blast ripped through the Mont-Blanc, detonating the ship with the force of a 3 kiloton bomb. The force of the explosion devastated both sides of the Narrows. Debris and pieces of the Mont-Blanc were tossed over a 5 mile radius as a noxious cloud of vaporized ship fuel rose skyward. Sally M. Walker, author of Blizzard of Glass, writes, "Alan Ruffman and David Simpson, two scientists who later studied the explosive power of Mont-Blanc's cargo, estimated that the temperature at the center of the explosion was about 9,032 degrees Fahrenheit. . . The initial speed of the shockwave. . . was about 5,000 feet per second — nearly five times faster than sound travels through air."

Halifax devastated

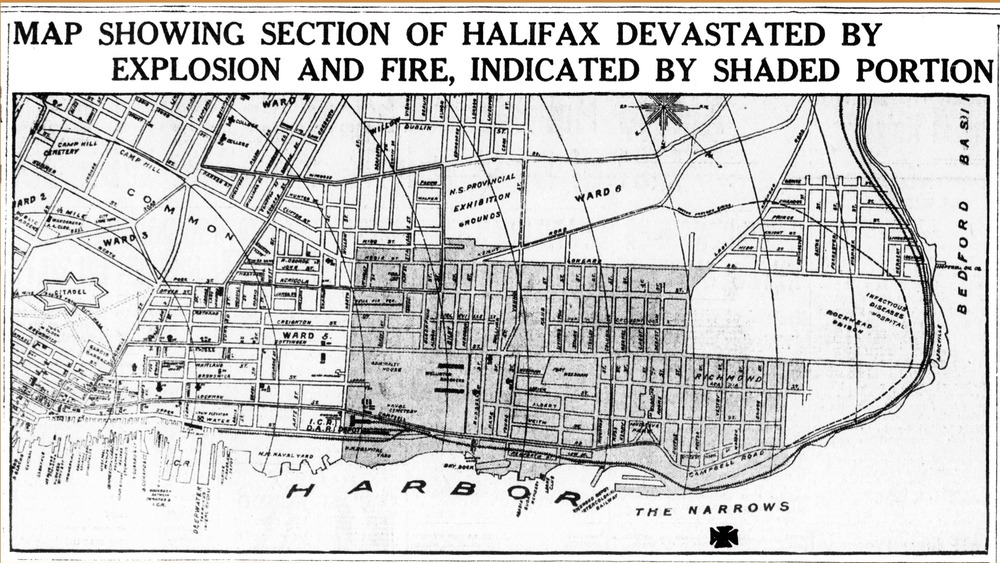

According to Disasters of Atlantic Canada: Stories of Courage and Chaos, by Vernon Oickle, the Halifax Explosion killed over 1,900 people. Another 100 would succumb to injuries in the following months. Approximately 9,000 were hurt in the blast. However, the true death toll may never be known due to the magnitude of the disaster.

Property damage was both immediate and immense. Most of Halifax's North End, an area of 130 hectares (half of a square mile), was completely destroyed. Halifax's Richmond district and Tufts Cove on the other side of the Narrows in Dartmouth took the full force of the blast. As recounted by Sally M. Walker, author of Blizzard of Glass, every building between the harbor, Fort Needham, Young Street, and Rector Street was reduced to rubble. Vital centers of industry such as the Acadia Sugar Refinery, the Richmond Printing Plant, and the Hillis Foundry were transformed into smoking heaps of blackened bricks in the blink of an eye. All of Richmond's churches, schools, and its orphanage were destroyed. In all, 12,000 buildings within a 16-mile radius were damaged.

Shattering windows nearly 50 miles away from the explosion, the blast could be felt as far away as Sydney, Cape Breton, 270 miles northeast of Halifax.

Water, fire, and snow

Although the blast itself was unprecedented in magnitude, its ancillary effects proved nearly as destructive. As recounted in Curse of the Narrows, the intense heat of the initial explosion in the hull of the Mont-Blanc vaporized the water in a 20-foot radius around the ship. As the pressure from the blast wave subsided, water rushed back in from all sides to fill the void. Survivors would later recall seeing the harbor's floor momentarily exposed as the water was sucked from the shore. As the waves crashed together, they created a towering column of water like a geyser. When the geyser collapsed under its own weight, it created a deadly tsunami. Ships, houses, and people were swept away in a 20-foot wall of water on both sides of the harbor.

However, the explosion and the tsunami were not the only destructive forces the citizens of Halifax and Dartmouth would face on Dec. 6, 1917. The blast overturned candles and oil lamps and damaged stoves igniting fragile wood framed homes and turning already decimated buildings into burning piles of kindling.

Compounding the destruction caused by the explosion, the tsunami, and the ensuing fires, a blizzard struck Halifax the next morning. Temperatures plunged to 16.8 degrees Fahrenheit as snow blanketed the ruined city. Consequently, the ice and snow delayed trains loaded with volunteers and medical supplies.

Wartime paranoia and persecution

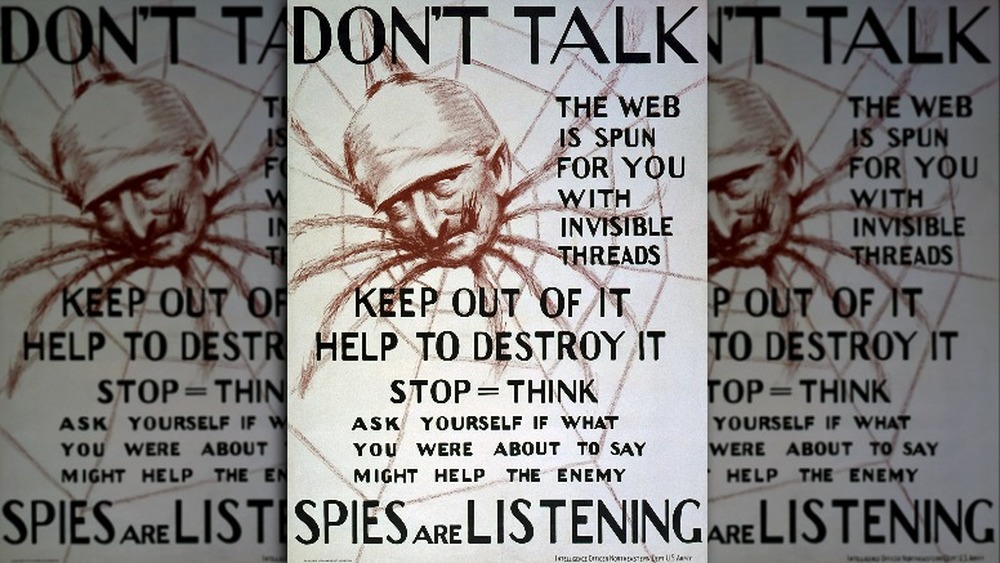

Once the survivors got over their initial shock and disbelief, many turned their attention to the real possibility of German sabotage. Even those who had witnessed the collision seemed convinced that the Germans were behind the blast. As detailed in The Curse of the Narrows, even the military was unsure about the cause in the first few hours after the disaster. Constant warnings about possible German attacks on the harbor had conditioned the citizens of Halifax to be hyper-vigilant. Throughout the day, nervous survivors scanned the skies for German bombers.

In the days following the explosion, anti-German sentiment ran rampant. The incensed survivors, convinced that they were the victims of a German attack, were out for blood. German survivors were attacked in the streets. On Dec. 10, 1917, the Halifax Herald announced that all Germans in Halifax were to be rounded up and jailed.

Wartime paranoia extended to the surviving crew members of the Mont-Blanc and the Imo. John Johansen, wheelman and sole surviving member of the Imo's bridge crew, came under scrutiny as a suspected spy when a German book was found in his possession. Injured and imprisoned, Johansen became the subject of a wild rumor stating he had murdered the Imo's captain and steered the ship into the Mont-Blanc. Further examination revealed that the book in question was written in Norwegian.

Ultimately, the alleged negligence of Mont-Blanc's Capt. Aimé Le Medec and pilot Francis Mackey would be cited as the cause of the collision.

A proud people wiped out

One of the most tragic incidents of a day replete with death and destruction was the near-total annihilation of the Turtle Grove enclave. A small community of Miꞌkmaq, Indigenous people native to Canada's Atlantic provinces, had inhabited Turtle Grove, also known as Tufts Cove, since the 17th century. As reported in a December 2017 article published in The Signal, Turtle Grove was composed of a handful of families, seven wigwam dwellings, and a school located on the Dartmouth shore.

For years, the Miꞌkmaq had been at odds with local landowners over the settlement. Deemed squatters on land they had lived on for centuries, the native people had been successful in retaining their hold on Turtle Grove. Yet, by 1917, they had endured enough intolerance from their white neighbors to appeal to the Department of Indian Affairs themselves about relocating. The move was scheduled for one week after the explosion.

Turtle Grove was completely decimated in the blast and ensuing tsunami. The tragedy did nothing to alleviate white prejudice against the Miꞌkmaq. Immediately after the explosion, whites accused the Indigenous people of rowing across the Narrows and looting the wreckage in Halifax.

Ultimately, the blast had done in seconds what white business interests had tried to do for decades. "The big thing that happens is the thing that doesn't happen," historian Jacob Remes told The Signal. "The school doesn't get rebuilt, the settlement is prevented from being rebuilt."

The tragic tale of Africville

Despite the unprecedented humanitarian mobilization of volunteers and supplies following the Halifax Explosion, the relief effort was nonetheless marred by racism.

As recounted in Curse of the Narrows, Africville, located on the Bedford Basin at Halifax's north end, was a growing community of working class African Canadians. The residents, many of whom were employed on Halifax's railway and dockyards, attended a small wooden church, enjoyed the amenities of three stores, and sent their children to Africville's school. Nevertheless, racist attitudes in Halifax branded the community a shantytown. Despite being tax-paying citizens, the residents of Africville were denied paved roads and water and sewer services.

Shielded by a hillside, Africville was spared the massive devastation that tore through Halifax and Dartmouth. Still, homes were extensively damaged and ten people lost their lives. Disbursement of relief funds for the Black community were reduced from the standard 20% for white residents to 10% of incurred losses. Often they received even less. "The person who was in charge of the reparations basically sent out a memo indicating to staff that blacks. . . who were applying for relief, their claims should be automatically be reduced 20 per cent — or ignored — and so this was a policy," David Woods, author of Extraordinary Acts, a play about Africville's struggles after the Halifax Explosion, told the CBC in 2017. Vital food allowances were discontinued to Black families without notice, and racism made temporarily relocating families to white neighborhoods virtually impossible.

The hero of Halifax

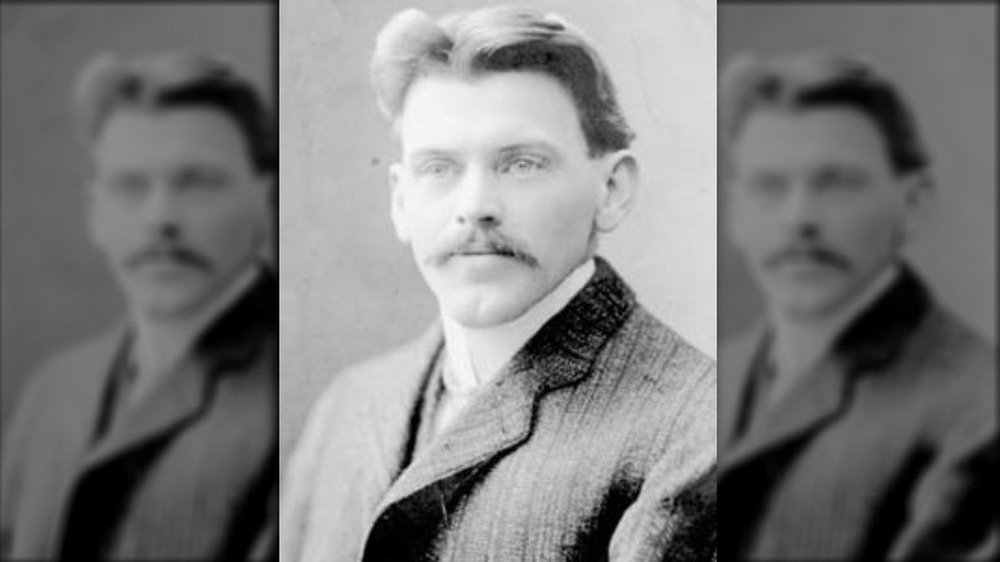

As recounted by the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Dec. 6, 1917, started like any other day for Vincent Coleman. He said goodbye to his wife Frances and 2-year-old daughter Eileen and walked the five blocks from his home on Russell Street to the Richmond train station where he worked as a dispatcher for the Canadian Government Railways. He took his usual position in the wooden station in the center of the station's railyard. Only feet from the water, Coleman had a clear view of the harbor and its traffic. No doubt, he anticipated another busy day of directing war-related rail traffic in and out of the harbor.

Soon after taking over from the night dispatcher, Coleman heard the dull crash of the Mont-Blanc and Imo's collision in the Narrows. From his vantage point, Coleman saw the thick black smoke rising skyward from the French munitions ship. In full understanding of the gravity of the situation, Coleman remained at his post and keyed a warning to an inbound passenger train from his telegraph — "Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys."

Moments later, Coleman died in the blast. His actions saved the lives of 300 rail passengers bound for Halifax from New Brunswick.

A tragedy too painful to remember

The great mystery of the Halifax Explosion lies not in the blast, or its deadly aftermath, but in the bizarre fact that it has gone largely unheralded and was, for a time, nearly forgotten. Simply, the devastation and loss of life proved too much to bear. To many survivors, the memories of that tragic day were best forgotten. The citizens of Halifax tended their injured, buried their dead, and turned to rebuilding their ruined city. The disaster was commemorated one year later. It would be generations before the explosion would again be publicly memorialized. A 1967 ceremony would be the first and last official day of remembrance until the opening of Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower at Fort Needham in 1985.

In a 2017 interview with The Canadian Press' Brett Bundale, explosion survivor Jim Cuvelier, a baby at the time of the blast, offered his thoughts on the community's reticence about discussing the disaster. "People tried to forget it," Cuvelier said. "You don't carry that stuff around."

The remaining survivors speak

In 2017, Canada observed the 100th anniversary of the Halifax Explosion. Although those who had witnessed the events of Dec. 6, 1917, firsthand had long passed, the youngest remaining survivors, infants at the time of the explosion, recounted how the disaster had impacted their lives.

Among them was Wanda Robson, sister of civil rights pioneer Viola Desmond. In an interview with CBC Nova Scotia, Robson told of her father discovering 3-year-old Desmond in her overturned high chair. "He said, 'I went to the high chair, and I picked up the blind which had fallen in on Viola's body. . .' And he picked up the blind. . . she was sitting there with her fists clenched and her eyes closed. . . she looked at him and she said, 'Papa, those bad boys throw stones at me.'"

However, the Desmonds soon discovered few had shared their luck. "There were bodies rolled up in the gutter," Robson said. "It was a disaster of history — a sad, sad history."