The Crazy Real-Life Story Of 1984 Author George Orwell

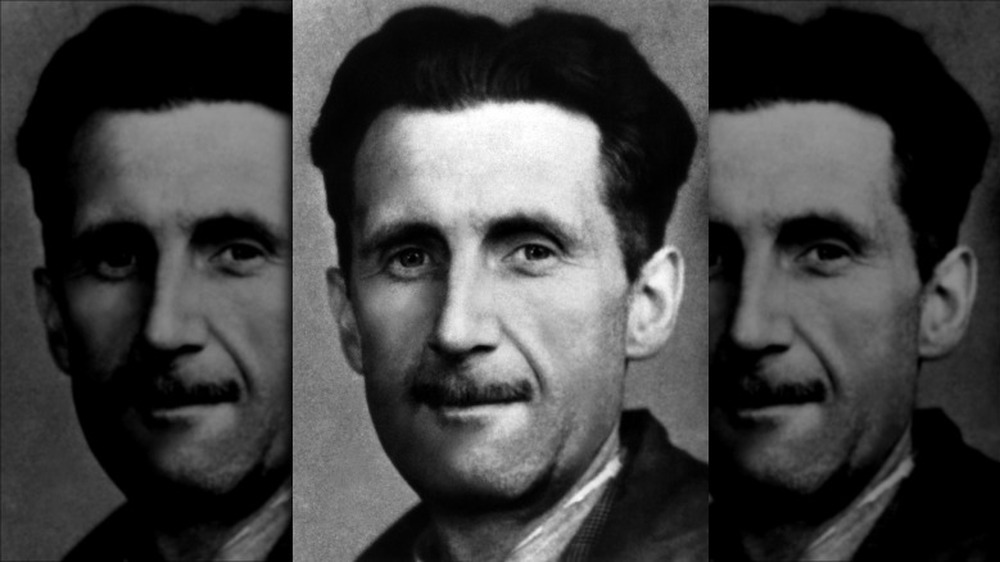

There's an old stereotype about novelists — that they'll do anything to get new material. In the case of George Orwell, one of the most quoted (and misquoted) authors of the 20th century, this certainly rings true. In fact, the British author had what can only be described as an almost pathological necessity to accumulate experiences through which to understand the world anew.

Born into a moderately wealthy family as Eric Arthur Blair in India in 1903, according to Biography, his father worked in the Indian Civil Service, overseeing the cultivation of poppies and the production and export of opium to China on behalf of the British Empire, per the BBC. Orwell's mother, who returned to England with her son and his older sister when he was just a year old, was from a cash-poor aristocratic background. And while her social connections secured her son a prestigious education at the famous Eton School for Boys, he failed to get a scholarship to go to university. Instead, the future author would begin a series of experiences that would come to inform his writing and instill within him one of the most influential political philosophies in English literature.

Today, that the white, middle-class Orwell came to describe lives of deprivation and subjugation may give off a whiff of inauthenticity, or, worse, poverty tourism. However, despite his background, most critics have been forthright in their claims that Orwell's humane articulation of his subjects was genuine.

George Orwell's transformative years in Burma

Portraits of George Orwell as a child and teenager don't tend to be especially flattering. Although his intellect was beyond doubt, his unusual familial background instilled in the boy some unpleasant attitudes. Orwell had his own term for the type of people his family was — "landless gentry," according to Britannica, "whose pretensions to social status had little relation to their income. Orwell was thus brought up in an atmosphere of impoverished snobbery." It was an attitude that Orwell would soon come to deplore thanks to his first major upheaval that he would undertake at the age of just 19.

With the path to university cut off from him, the young Orwell decided to apply as an Imperial Police officer in Burma (pictured), which was still under British rule at the time as a Province of British India. Orwell arrived in 1922 and would remain in Burma until 1927, by which time he was utterly disillusioned with and embarrassed by British colonialism and the subjugation of those who found themselves under its control. While there, Orwell distinguished himself from his fellow officers by learning the local language and immersing himself in Burmese culture. "It was during those years that he was transformed from a snobbish public-school boy to a writer of social conscience who sought out the underdogs of society," wrote the academic Emma Larkin in her introduction to his memoir of his experiences, Burmese Days, first published in America in 1934.

George Orwell joined the Down and Out

In Orwell: The Transformation, Peter Stansky and William Abrahams claim that when George Orwell "returned to England from Burma, and resigned his commission in the Indian Imperial Police, he was not prompted by some vague literary-romantic yearning. He knew, in the most ruthless and determined way, that he wanted to be a writer." Orwell's return after five years abroad was the moment of a great literary awakening, made all the greater by his new perception of English society due to his experiences in Burma. Orwell, who went to do the work of imperialists but soon sympathized with the poor Burmese, and through drawing parallels between the forces of the British Empire and the famously cruel and divisive English class system, came to see in England a country of great social injustice.

In many ways, what Orwell brought back with him from Burma was a burning sense of guilt, which, as Britannica puts it, "he thought he could expiate ... by immersing himself in the life of the poor and outcast people of Europe." Orwell began to integrate into the lives of the homeless and destitute, dressing in rags and using a pseudonym. In this way, he joined the multitude of "tramps" who, as one of his early essays describes, were forced to walk up to "twenty kilometres a day" between "spikes" — boarding houses for the homeless that, due to the masses of unemployed Britons in the period, only permitted people to stay one night in per month.

George Orwell's double life

After a period of a few months' acquaintance with London's destitute populace, George Orwell (pictured) upped sticks and moved to Paris, where he stayed for 18 months while continuing to write, according to France Today. As a dishwasher, Orwell lived in slum dwellings and experienced first-hand the slavish working conditions of Paris' upmarket restaurants and hotels. On his return to London, the writer attempted to ingratiate himself with the poverty-stricken poor of the city by committing fully to his "tramp" identity, sometimes for months at a time.

Yet Orwell lead a double life. Though he lived frugally and survived on very little during these years, he was still supported financially, when necessary, by his mother in England, and, while in Paris, and aunt who lived in the city — Nellie Adam, according to Peter Stansky and William Abrahams.

Orwell returned and undertook a lengthier "immersion" into "the world of abject poverty," living with the homeless for months on end — albeit in secret in case the fact might shame his family. Orwell's project was the catalyst for his transformation into a true writer, with the 1933 publication of Down and Out in Paris and London.

George Orwell tried to get himself arrested

George Orwell's (pictured) investigations into abject poverty were, however, afforded authenticity by the fact that he did experience extreme poverty several times during this period, according to his biographer D.J. Taylor, which coincided with bouts of illness that continued to plague him since childhood. As well as these sporadic weeks of very real pennilessness, the sincerity of Orwell's literary project can also be gleaned by the extremes to which he was willing to live through and document the hardships of those he observed.

As well as living among the "tramps" in "spikes" and working short-term poorly paid jobs, Orwell claimed, in a 1932 essay titled "Clink," that he also purposely attempted to have himself arrested so that he might experience the realities of time in prison. According to Melville House Publishing, the essay chronicles how Orwell intentionally got as drunk as possible before falling into the path of two London police officers, who took the writer to the holding cells to sober up and was released within 48 hours with a warning.

The details of Orwell's autobiographical writing have always been in doubt, with many academics questioning the veracity of Down and Out in Paris and London, the book written about Orwell's experiences that first made his name. But in 2014, the The Guardian reported that police records showed that Orwell's arrest did indeed take place, which in turn has lent many of his early texts greater believability.

George Orwell rebelled against the middle class

"Clink" was published in the literary journal New Adelphi, for which George Orwell also contributed book reviews and other essays — among them included recollections of his time in Burma. But in addition to his literary pursuits, it was also necessary for Orwell to find more regular paid work. He had a stint as a teacher, which ended abruptly thanks to a serious bout of pneumonia. According to the Orwell Foundation, Orwell then went to stay and recover with his mother in Southwold and never returned to the profession. Instead, the author worked on a second book, A Clergyman's Daughter, which would be published in 1935.

Orwell moved to London, where, through his literary friends at the Adephi, he landed himself a cushy job working afternoon shifts in Booklovers' Corner, a relaxed bookshop in bohemian Hampstead, according to Peter Stansky and William Abrahams, leaving the rest of his time free for writing. The period was one of the most settled and productive of Orwell's adult life, and it was during this time that the otherwise eccentric writer did something utterly conventional — meet the woman who was to become his wife, Eileen O'Shaughnessy.

But Orwell did not settle into complacency. Instead, his aversion to the trappings of bourgeois life grew even more pronounced, and in 1936 he published Keep The Aspidistra Flying, a seething critique of the middle classes.

George Orwell chronicled northern poverty

By the late 1930s, George Orwell had matured as a writer, and the recurrent themes of class imbalance and social injustice became central to his work. As such, he began to receive commissions on subjects publishers knew he could tackle well.

One of these came from the publisher of Down and Out in Paris and London, Victor Gollancz, who, according to Penguin, gave Orwell the task of traveling to the industrial, poverty stricken north of England and producing a volume describing the appalling living and working conditions there, particularly for coal miners, mill workers, laborers, other industrial workers, and the huge numbers of unemployed men in the region at the time. The book, The Road to Wigan Pier, ended up being two parts — the first comprising descriptions of the scenes of destitution that Orwell found in the north, and the second being an extended and vicious denunciation of the class structure, explaining in depth the benefits of socialism as an alternative, as per The Guardian.

The book, per Penguin, made a huge impact thanks to being selected as a choice for the Left Book Club, which vastly increased the number of copies printed and circulated to just under 50,000, a huge figure at the time.

George Orwell fought fascists in the Spanish Civil War

It is likely that the polemical second half of The Road to Wigan Pier sharpened George Orwell's burning desire for political and social justice rather than expunged it. The fact was, Orwell wasn't even in England to see its first publication in 1937. Instead, he had already traveled abroad to serve in the Spanish Civil War.

"The civil war had been triggered by an attempted right-wing army coup in July 1936 against the elected, left-leaning Republican government. Only half-successful, rebelling army garrisons were resisted in key cities like Barcelona and Madrid," says Jacobin Magazine. Orwell arrived mere months after the fighting started, aged 33, and quickly enlisted with the POUM, a communist political party.

Orwell was steadfast in his repulsion towards fascism, though critics have argued that his grasp on the true social catalysts underpinning events was tentative (years later, Juan Negrín, exiled minister and former leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, described Orwell as "idealistic and unworldly," according to the The Guardian). But the degrading reality of warfare — however righteous one's beliefs — is what stuck with him, writing in "Looking Back on the Spanish Civil War" in 1942, "A louse is a louse and a bomb is a bomb, even though the cause you are fighting for happens to be just."

Orwell engaged actively in the fighting on the Aragon front, per Hektoen International, and was seriously injured after being shot through the throat by a sniper's bullet.

George Orwell made himself useful in WWII

Even before he received the wound that almost ended his life, George Orwell's final months in Spain were dispiriting, dominated as they were by infighting between previously allied anti-fascist factions. After the suppression of the POUM by pro-Stalinist forces and a course of electroshock therapy in a hospital in Barcelona, according to Hektoen International, as well as Orwell and his wife receiving the prognosis that Orwell's voice was gone permanently, the couple returned to England in 1937, where Orwell continued to recover and began to write up his experiences. The resulting book, Homage To Catalonia, would be released in April 1938.

Britain entered World War II in 1939, and once again Orwell's harrowing experiences did little to blunt his enthusiasm for putting himself forward for service. However, according to Britannica, Orwell was rejected for active military service due to the severity of the injuries he received in Spain (his right arm had also been badly injured and was paralyzed for five months). But the now-esteemed writer made sure his skills were put to use, by joining the BBC, per Britannica, and heading the Indian arm of the corporation to broadcast "counter-propaganda" against the Nazis. He also joined the British Home Guard, a "volunteer army" that the British Library claims, "he praised ... and argued that only a non-authoritarian state such as Britain would have freely distributed arms to volunteer troops."

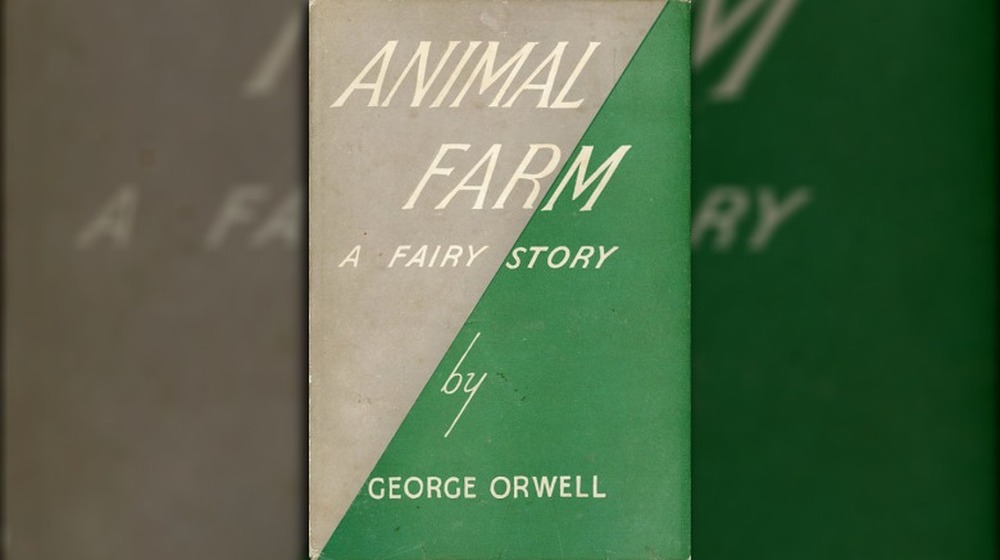

Animal Farm and international fame

It was during World War II that George Orwell began work on one of his most enduring and oft-quoted works – Animal Farm. The novella, an allegory concerning the shifting allegiances of a group of farmyard animals that warns of the perils of allowing totalitarians to hoard political power, was delayed in its publication, according to Encyclopedia.com, due to the perception from his publishers that the book could be read as a retelling of the Bolshevik revolution and an indictment of Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union, who remained key allies of Britain until the end of the war and the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Orwell's tale of the animals' rebellion against the farmers that reared them and the irresistible rise of Napoleon the pig and his band of deceptive and ultimately self-serving swine became an immediate international hit, writes D.J. Taylor, raising Orwell's profile enormously. Originally subtitled "A Fairy Story," the book allowed a world of readers traumatized by the horrors of war they had just experienced to reflect on what they had lived through for the past half decade, and it has remained in print ever since.

According to the Metro, Animal Farm was banned in the Eastern Bloc until its collapse in 1989.

The tragic death of George Orwell's first wife, Eileen

The end of World War II and the success of Animal Farm were overshadowed by one of the most tragic events of George Orwell's life — the untimely death of his wife, Eileen, at the age of 39.

As with many women throughout literary history who have supported great male writers, the full details of Eileen's life and the many sacrifices she made for her husband's writing career have been neglected by historians until fairly recently. The New Statesman goes as far as to argue that Eileen "married an unknown writer and then worked herself to death to ensure his fame." The article describes how Eileen, upon meeting George, left her own career as an academic for his sake, typing his manuscripts and taking care of the numerous animals that George took in during his recovery following his time in Spain, while George himself wrote and recuperated.

George and Eileen adopted a son, Richard, in 1944, but Eileen's time as a mother was not to last. According to the The Guardian, she died less than a year later, due to complications arising while under anesthetic for a hysterectomy. Typically, Eileen had tried not to worry George by sharing with him the seriousness of her illness, and her tragic death was a great shock. Animal Farm was published less than six months after Eileen's death in March 1945, while George, in mourning, threw himself once again into his work.

George Orwell was seriously ill when he wrote his masterpiece

"When people use the adjective Orwellian today, they're almost invariably talking about '1984,'" says NPR's Petra Mayer. And it is true that George Orwell's final work is undoubtedly his greatest and most enduring. The novel, "set in an imaginary future in which the world is dominated by three perpetually warring totalitarian police states," as described by Britannica, tells the tale of Winston Smith, an everyman who learns to rebel against a life of surveillance, conformism, and thought control.

But though Orwell was reaching the zenith of his artistic powers when he began 1984, his health was failing. Orwell had been sickly since an early age, and D.J. Taylor describes how the writer's war would seemed to coincide with a form of chronic lung disease, most likely exacerbated by the dank, insanitary conditions Orwell had forced himself to reside in during his many adventures, as well as his heavy smoking habit. He was diagnosed with bronchial problems, but by the mid-1940s, Orwell was suffering with tuberculosis and coughed up blood on numerous occasions. However, he made efforts to hide his condition, while continuing to work on 1984, alternating periods in the hospital with long stays on the peaceful Scottish island of Jura (pictured), where he finished the book.

George Orwell died less than a year after 1984 was published

George Orwell eventually succumbed to his illness and passed away at London's University College Hospital on Jan. 21, 1950. He was 46. Mere months before his death, Orwell married Sonia Brownell, a 31-year-old fellow Etonian who nursed him and, upon inheriting his estate, "proved herself a devoted, if combative, steward of his legacy," according to the LA Times.

And it is true that Orwell's legacy has continued to grow in the years since his death. In 2008 for example, Orwell was ranked at number two in The Times' list of the "50 greatest British writers since 1945" (behind the poet Philip Larkin). But more telling than articles reminding us of the writer's "greatness" are those that reveal how fundamental Orwell's writing remains as a prism through which to analyze politics today. According to the Independent, Donald Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway's reference to "alternative facts" back in 2017 led copies of 1984 to sell out on Amazon, as readers turned to Orwell for insights into how politicians attempt to twist reality with words. However, whether developments in tech might be described as "Orwellian" is a continuous debate.