The Untold Truth Of The Boiler Room Girls

"Behind every great man is a great woman." It's an old saying, and nobody seems to really know exactly where it comes from. Still, there are plenty of examples throughout history that would prove it, with wives allowing for their husbands to rise to positions of power.

But that phrase doesn't need to apply only to wives. Really, there have been groups of women throughout the past who ultimately served as the backbone for major historical events, though their stories have largely gone untold. When it comes to politics, the Boiler Room Girls, the group of six women providing necessary services and support to the Kennedy family in the late 1960s, would definitely fall into this category.

Given the fame — or, in some cases, infamy — surrounding the Kennedys in the U.S., it's surprising that the contributions of the Boiler Room Girls aren't really talked about in detail decades later. But, then again, given the tendency of the press to look for scandal, maybe relative anonymity isn't too bad, especially considering the tragedy involved in this story.

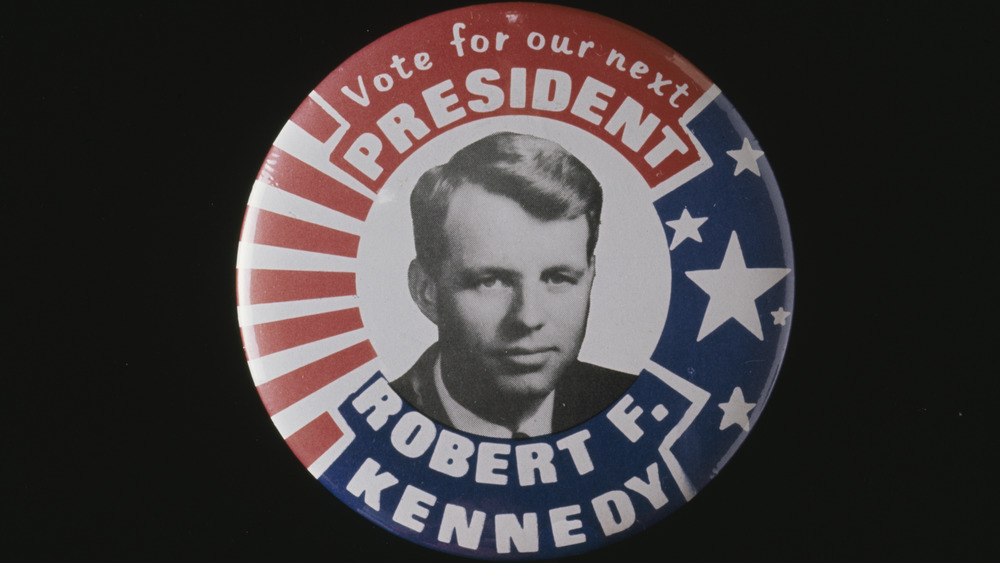

1968 was an election year

In the midst of the Vietnam War, it'd be a bit of an understatement to say that the everyday American citizen was in need of a little hope. As stated by Thurston Clarke in his book The Last Campaign, just about all of the candidates were promising an end to the Vietnam War, but one stood out in particular. Senator Robert F. Kennedy, the younger brother of John F. Kennedy, was running to be the Democratic Party's presidential candidate for that year's election, and he was running a different campaign from those of his opposition.

He didn't make promises that, as president, he would fix all the problems that the nation was facing: Instead, he asked that the people themselves look deeper and recognize the part that they could all play in repairing those problems. And, on top of that, his campaign stressed more than just the war but also internal issues like racial discrimination and poverty, as he asked his supporters to heal those divisions through their compassion.

Ultimately, his strategy worked, and it worked well, setting him apart as one of few politicians who was trusted by people from all walks of life, regardless of the usual divisions like social standing, wealth, and race. Massive crowds would gather to support him, even chanting "We want Bobby!" on occasion, like they did in Los Angeles, California, on the night of RFK's assassination (via ABC News).

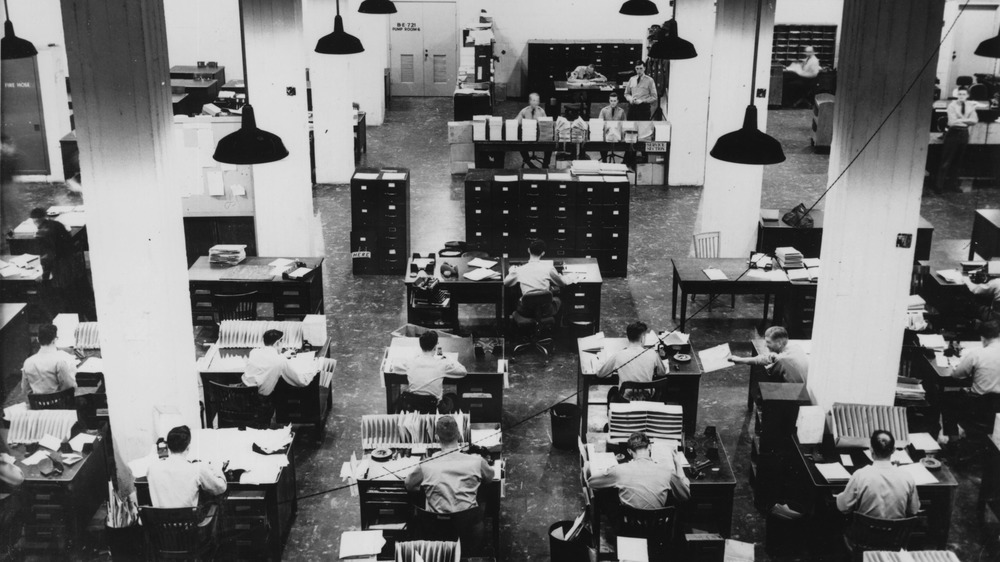

The Boiler Room Girls worked for Kennedy's campaign

Of course, there's more to a political campaign than the candidates themselves, and the Boiler Room Girls were a handful of the staffers ensuring that RFK's campaign ran smoothly. The group included Rosemary "Crickett" Keough, Mary Jo Kopechne, Susan Tannenbaum, Esther Newberg, and Maryellen and Nance Lyons, with the women's name coming from the windowless room that they all worked in, according to William C. Kashatus' book Before Chappaquiddick.

The Boiler Room Girls also acted as secretaries to other members of the staff working on Kennedy's campaign, but together, they had the task of manning the phone lines. Each assigned a different area of the country, they monitored the data, keeping track of how it seemed that the Democratic delegates would vote at the convention and staying in contact with both field managers and the press. It wasn't an easy job, and even a summary provided by TIME regarding a later court inquiry recognized their intellect, calling them "uniformly bright, efficient, [and] fascinated by politics."

Each of the Boiler Room Girls was talented on their own

Despite being largely overlooked and fading into anonymity in the time since the 1960s, all of the Boiler Room Girls were individually talented, with impressive résumés and ambitions that brought them into the fold of Robert Kennedy's campaign. They were even more impressive given the time period, and it'd be a shame not to, at the very least, mention what they'd already accomplished before joining the 1968 campaign, as summarized by TIME and an interview with Barbara J. Coleman.

Keough had experience volunteering during John F. Kennedy's presidential campaign in 1960 before joining Robert Kennedy's campaign in 1967 and was initially there to answer mail from children. Tannenbaum attended Centenary College and Miami University and then joined Kennedy's campaign in 1967, working in the mailroom.

Nance Lyons graduated from Newton College of the Sacred Heart and did PR for Norfolk County Tuberculosis and Health Association. Her sister, Maryellen Lyons, studied at Regis College and worked for a protégé to Ted Kennedy, who then recruited both of them.

Newberg had worked on a Senate subcommittee meant to reorganize the government and also had experience working with the Democratic National Committee through her mother, while Kopechne graduated from Caldwell College and went into public service, working as secretary in the Senate.

The Boiler Room Girls didn't work on RFK's campaign for long

Sadly, the entire campaign was cut cruelly short, because June 5, 1968, is known for a lot more than an especially joyous crowd crying out to see Bobby Kennedy. ABC News recounts that this when, not long after midnight, Kennedy was in the Embassy Room of Los Angeles' Ambassador Hotel to announce his victory in the California Democratic presidential primary — definitely a cause for celebration.

But that good mood was spoiled when a gunman appeared and fired shots at the senator, who was making his way through the hotel's kitchen. Six people were hit in the chaos, but it was RFK who suffered the worst injuries, a fatal shot through the skull leading to his death the next day. The assassin, Sirhan Sirhan, was caught and convicted for the crime (although some really strange speculation has arisen regarding his guilt since then), but the damage was done.

The Boiler Room Girls disbanded shortly after, but the assassination had further effects. Huge crowds gathered around Kennedy's funeral procession to say their goodbyes, and later scholars saw that as a moment when Americans began to lose hope in the idea of peace, having watched those dreams of a better future come apart at the seams (via U.S. News).

The Boiler Room Girls returned to work in politics

Much like the rest of the country, the Boiler Room Girls were devastated by the assassination, though, after a little bit of time, most of them did end up returning to work in various areas of politics, under a number of different politicians. Keough was hit the hardest by RFK's death, but she eventually went on to work with the Kennedys' foundation for mentally disabled children, as stated by TIME. Tannenbaum moved to work under Representative Allard Lowenstein, who helped start the "Dump Johnson" movement, and Newberg ended up assisting the vice president of the Urban Institute in Washington. Nance Lyons did casework for Edward Kennedy, while Maryellen switched to work for Massachusetts senator Beryl Cohen. Kopechne moved on to work for a campaign advisor active in Washington.

Aside from their own ambitions, the Boiler Room Girls also worked in the positions that they did because it afforded them a pretty nice level of anonymity. Nance Lyons specifically said that staying anonymous was the goal for anyone on a politician's staff, and Tannenbaum made similar comments, remarking on her own personal value in privacy. Actually, most of the girls would end up agreeing to stay silent and out of the public eye within the next couple years, though the reason for that was, unfortunately, also rather tragic.

Mary Jo Kopechne became widely known at the time

Mary Jo Kopechne ended up being something of an outlier when it came to anonymity, but not through any fault of her own. Really, she came from pretty humble beginnings, as detailed by William Kashatus. Born in a small Pennsylvania town in July 1940, Kopechne was an only child with two loving parents who wanted to afford her every opportunity that they could. On the whole, though, the family was described as quite insular by others in the town, and it was a trait that Kopechne inherited, too, being described as fairly introverted by childhood friends.

On the topic of anonymity, Kopechne actually considered becoming a nun, for a while. But that changed after she heard John F. Kennedy's famous "Ask not what your country can do for you" speech, which pushed her into public service and ultimately led her into the Boiler Room Girls.

All of that — everything about her background — is perfectly normal. Completely inconspicuous. So how did a kind, socially minded introvert become a central point in national news? The answer is her early death in a situation called the Chappaquiddick Incident.

The Chappaquiddick Incident

In July 1969, a party was thrown in honor of the Boiler Room Girls on Chappaquiddick Island, off the coast of Massachusetts, as described by ABC News. The six girls all attended, along with a handful of other guests — mostly other Kennedys as well as friends of the family. That included Edward "Ted" Kennedy, the youngest of the Kennedy brothers, a man characterized by Kashatus as a virtuous senator when the cameras were on but an entitled womanizer once those cameras were gone.

Late that night, Mary Jo Kopechne accepted an offer from Kennedy to drive her back to her hotel, but she never made it. According to Kennedy's later statements, he managed to make an incorrect turn, missing the main, paved road and heading onto an unmarked dirt road. That dirt road led to a bridge over a nearby lake, and the car somehow fell into the water. Kennedy managed to escape the sinking vehicle and claimed to have attempted to save Kopechne, citing panic as the reason he couldn't succeed.

Kopechne's body wasn't found until the next morning, no thanks to Kennedy. He actually didn't even report the accident until after her body had been found. Local authorities had already been made aware of the situation because a couple of boys had seen the submerged car while they were fishing, as reported by the Owosso-Argus Press.

The aftermath of the Chappaquiddick Incident

The fact that Kennedy didn't immediately report the incident is just one of many strange aspects of this case: The Owosso-Argus Press called out those inconsistencies at the time. Kennedy later claimed to be unfamiliar with the paved road, but witnesses had seen him drive it multiple times that weekend. Even then, why would he have followed the dirt road for over half a mile? Plus, why did it take so long for him to report the accident?

The proceedings afterward didn't really make things look any more legitimate, either. For some reason, no autopsy was performed on Kopechne's body (via TIME), and a member of the rescue team, John Farrar, had reason to believe that Kopechne died of suffocation rather than drowning. (She may have remained alive for a time due to an air pocket in the car, until the oxygen ran out.) Long story short, Kopechne might have survived if Kennedy had reported the accident earlier (via ABC News). But Farrar wasn't allowed to speak at a court inquiry, and Kennedy was only given a two-month sentence, which was suspended. The public forgave him, re-electing him to the Senate over and over.

As for Mary Jo Kopechne? At best, she became a "footnote in her own death," as her cousin put it: The news headline "Teddy Escapes, Blonde Drowns" sums it up. But at worst, the public blamed her for the entire thing, Kashatus says. Journalists wanted to assume that she'd had an affair with Kennedy and ultimately faulted her for dirtying his record and ruining his chance at the presidency.

Sadly, blaming Kopechne probably wasn't entirely unexpected

All told, the 1960s weren't an especially welcoming time when it came to women in politics. Sure, it was a step up from the previous decade — the 1950s saw a decreasing number of women attending college as they were instead forced into the domestic lives of housewives, as explained by the United States House of Representatives: History, Art, & Archives. In comparison, the 1960s were a decade of change, with U.S. News describing how feminism had begun to take a greater hold as more women entered the workforce and began to expect equal opportunities.

But that didn't make the political scene any easier. Yes, women were beginning to find their way into office — but not without major backlash. Female members of Congress noted that they constantly had to monitor how they ran campaigns, because appearing too weak or too aggressive could spell disaster. But that criticism wasn't saved only for specific female politicians or for specific circumstances. Regardless of capability, there would always be people insisting that a woman's place was in the home, and rumors would fly constantly, threatening to ruin their careers (and sometimes even succeeding in doing so).

The Boiler Room Girls suffered similar treatment

Aside from the way the press chose to drag Mary Jo Kopechne's name through the mud in the wake of the Chappaquiddick Incident, the Boiler Room Girls were also subjected to inequality in the workplace, albeit in slightly different ways. In a 2008 interview, Nance Lyons, one of the Boiler Room Girls, talked about her experience working for the Kennedys and in politics in general.

On the whole, there just weren't a lot of women on staff for senators, and the few women who were often had men doubting their positions. It was either that, or the women were just assumed to be someone's secretary. And that assumption wasn't exactly unfounded, with plenty of women who had received college educations finding themselves relegated to secretarial work.

In the office, this view led to a double standard that Lyons began to notice. When the receptionist left, there was a silent expectation for the women to fill that role but never the men. Even in the case of women who were able to step into more important positions with real legislative work, they weren't allowed a secretary. On the other hand, Lyons was once replaced so that a secretary could be hired for two men.

Most of the time, though, Lyons was ignored so long as she was working. Or, at least, that was the case until the Chappaquiddick Incident: She felt that the staff blamed her for ruining Kennedy's political future and left sometime later.

Even in the decades since, there have still been problems

In her 2008 interview, Nance Lyons ends by talking about how the problems of the past aren't strictly relegated to the 1960s. Despite her own successful career as a lawyer, she sees that women are still being held back, even if those restrictions aren't as obvious as they were decades ago. Differences in pay, the relatively few women in U.S. politics, Hillary Clinton's loss in the 2008 election — there's still a glass ceiling, according to her, even if most people don't see it.

But she also talked about the lasting scars left by the Chappaquiddick Incident, despite the relative silence the Boiler Room Girls have kept since. The incident itself was tragic — all of them had lost a good friend — but no one really cared. They were portrayed as nothing more than party girls, despite the work they had done for Robert Kennedy's campaign, and the next decade of anniversaries saw them hounded by the press or receiving hate mail.

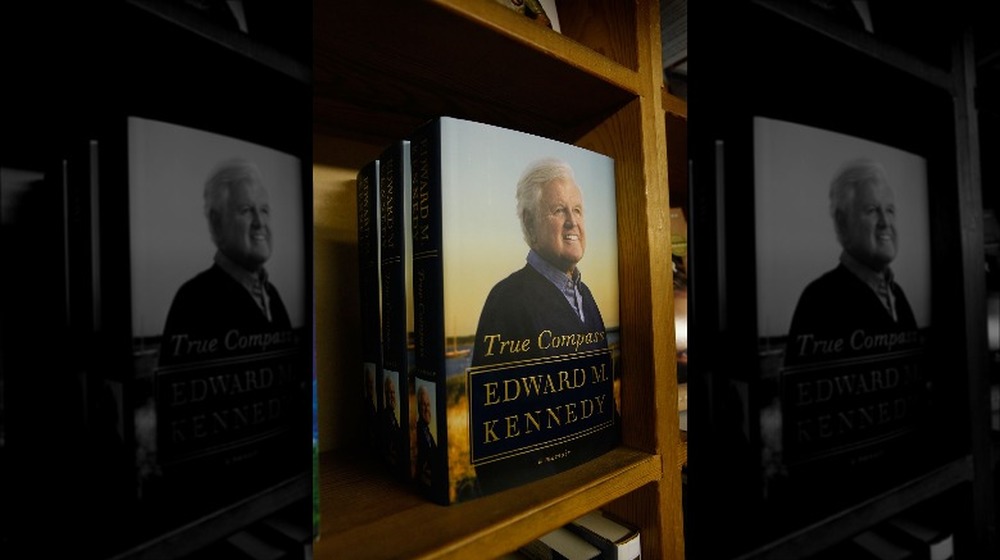

Ted Kennedy hardly made things any better, never checking whether they were alright and never even bothering to apologize to Kopechne's parents, according to Kashatus. Even in his final memoir, True Compass, Kennedy himself claimed that Lyons had been the one to convince him to go to Chappaquiddick in the first place. It just seemed to Lyons like a bold lie, the end of a long-winded attempt at destroying the reputation of the Boiler Room Girls.