The True Story Behind The Pentagon Papers

A researcher blows the whistle on decades worth of covert U.S. government dealings to sow warfare in Indochina (the Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos peninsula) by passing along classified, photocopied documents to a New York Times journalist. That journalist releases his informant's story without consent — a fact revealed only as recently as January 7, 2021, after the journalist passed away — and when President Nixon illegally retaliates, leads to one of the biggest scandals in modern presidential history: Watergate, as well as Nixon's impeachment.

This is the story of the Pentagon Papers in a nutshell, per History, dramatized as recently as 2017 in Stephen Spielberg's stellar tour de force The Post. The release of the Pentagon Papers — the moniker for the actual leaked documents — is a landmark case not only for bringing abuses of power to heel, but for how it redrew the relationship between government and the press. That is to say, no one is above the law, and the simple power of facts and words can change history.

The story begins after World War II when the U.S. government sought to protect its newfound status as a superpower and flex its muscles in the Pacific. Enter a clear-cut villain: "communists." The Cold War, primarily thought of as between the Soviet Union and the U.S., roped Vietnam into the mix, as History recounts. It was governmental dishonesty regarding these events, and its policy and strategy in Indochina, that yielded the Pentagon Papers.

Formed amid the divisiveness of the Vietnam War

Following Japan's withdrawal from Vietnam after World War II, a power vacuum developed in the country. On the surface, the U.S. got involved to protect the Republic of Vietnam in the south against sympathizers toward the country's communist north, led by Ho Chi Minh. This caused the Vietnam War, one of the most divisive conflicts in U.S. history, which lasted a full 20 years, from 1955 to 1975. It caused the deaths of more than 3 million people, nearly half of whom were Vietnamese citizens, and left 500,000 U.S troops with PTSD. It also engendered an entire generation of antiwar sentiment in the U.S., evidenced in music ("Blowin' in the Wind," "Bring 'Em Home," "Fortunate Son," per the Council on Foreign Relations) and films (Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, Apocalypse Now, per Esquire).

In the words of Neil Sheehan, the New York Times journalist who broke the truth about the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, "I wonder, when I look at the bombed-out peasant hamlets, the orphans begging and stealing on the streets of Saigon and the women and children with napalm burns lying on the hospital cots, whether the United States or any nation has the right to inflict this suffering and degradation on another people for its own ends." Sheehan, as The New York Times reports, passed away on January 7, 2021, at the age of 84, but not before his legacy had been long-cemented.

Built on the back of U.S. meddling in Indochina

In 1967, as Air Force Magazine writes, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara created the The Vietnam Study Task Force to develop an "encyclopedic history of the Vietnam War." He didn't tell the president at the time, Lyndon B. Johnson, about it because, "It was hardly a secret... nor could it have been with 36 researchers and analysts ultimately involved." It the end, the study consisted of 47 volumes of historical research and government documents 7,000 pages long. This body of work, later called "The Pentagon Papers," was officially titled, "US-Vietnam Relations, 1945-1967: History of US Decision Making Process on Vietnam Policy."

The documents revealed, as Britannica explains, that the U.S. had been waging a covert war against North Vietnam to try and prevent a takeover of the south, thereby limiting the expansion of a potential ally of the Soviet Union. The Truman administration (1945 – 1953) had given military aid to France, who had previously colonized Vietnam and lost control in 1954. The Eisenhower administration (1953 – 1961) continued to try and destabilize the north, and JFK (1961 – 1963) doubled down on this policy. Under his administration, most shockingly of all, as Newsweek cites, the U.S. "played an active role in the 1963 overthrow and assassination of President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam."

By the time Johnson inherited the war in 1964, it was still a full year before the American public knew a thing.

Formed from the guilt of a single former marine

By the time 1965 rolled around, Johnson decided to straight-up bomb North Vietnam and make U.S. involvement explicit, despite the intelligence community's insistence that it wouldn't deter Ho Chi Minh's forces in the north or south. Over the next decade, until Nixon ordered troops withdrawn in 1973, and the war officially ended in 1975, the U.S. continued to commit more and more soldiers to a losing cause. While at the same time, the government never revealed its true intent in the region to the American public and lied about how poorly the war was going. Ironically, and pointedly, the forces of North Vietnam wound up winning, anyway. In 1976, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam was formed, and the name of the capital of the south, Saigon, changed to Ho Chi Minh City, which it remains to this day.

Among the war's detractors was former marine and strategic analyst for the Department of Defense and the RAND Corporation, Daniel Ellsberg. Ellsberg helped draft the Pentagon Papers in 1967, and his disillusionment reached a head in 1969 when he attended a conference about the legal consequences of resisting the war efforts. Per The New York Times, the phrase "we are eating our young" stuck in his head, replaying over and over. As CBC News discussed in a 2018 interview with Ellsberg, Ellsberg went on to photocopy all 7,000 pages of the Pentagon Papers in secret, at night, over the course of months.

Published from the rebelliousness of The New York Times

As soon as Ellsberg had his documents in order, he reached out to journalists. The aforementioned Neil Sheehan at The New York Times was eventually the one to break the story, but Ellsberg in the meantime contacted nearly 20 publications total, as The New York Times states. By all accounts, he was understandably nervous about handing over the Pentagon Papers, particularly because he was afraid of jail time. At Sheehan's urging, Ellsberg settled on The New York Times because, "Only the Times might publish the entire study, and it had the prestige to carry it through."

However, Ellsberg didn't actually hand over the Pentagon Papers to Sheehan, nor did he give direct permission for Sheehan to publish them. Sheehan, as he revealed in a 2015 New York Times interview only made public after his death, did to Ellsberg what Ellsberg had done to the government: smuggled Ellsberg's documents and made copies in secret. From a Manhattan hotel room, Sheehan and his team painstakingly compiled and organized the report and prepared it for publication. In Sheehan's eyes, Ellsberg was too fidgety and behaved recklessly. The Pentagon Papers were at risk, he felt, and so he decided to deceive his source and the story's whistleblower for the greater good.

On June 13, 1971, the story made its way to the front page of the Sunday news, next to a piece on the wedding of Nixon's daughter.

Crafted amid the Supreme Court's protection of free speech

The very next day, the Nixon administration fired back. The New York Times' law firm, Lord Day & Lord, had warned against reprisal, and now the United States' attorney general, John N. Mitchell, was demanding that publication of the Pentagon Papers cease, "Further publication of information of this character will cause irreparable injury to the defense interests of the United States." The Times refused, and the government sued.

This is when the The Washington Post (the central subject of Spielberg's movie, The Post) jumped into the mix. Ellsberg reached out through an intermediary to The Post and forked over another copy of the Pentagon Papers. By June 18, Assistant Attorney General William H. Rehnquist demanded The Post stop publication, as well. They also refused and were dragged into the legal proceedings.

In the end, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the press, per History, stating, "In the absence of the governmental checks and balances present in other areas of our national life, the only effective restraint upon executive policy and power in the areas of national defense and international affairs may lie in an enlightened citizenry — in an informed and critical public opinion which alone can here protect the values of democratic government."

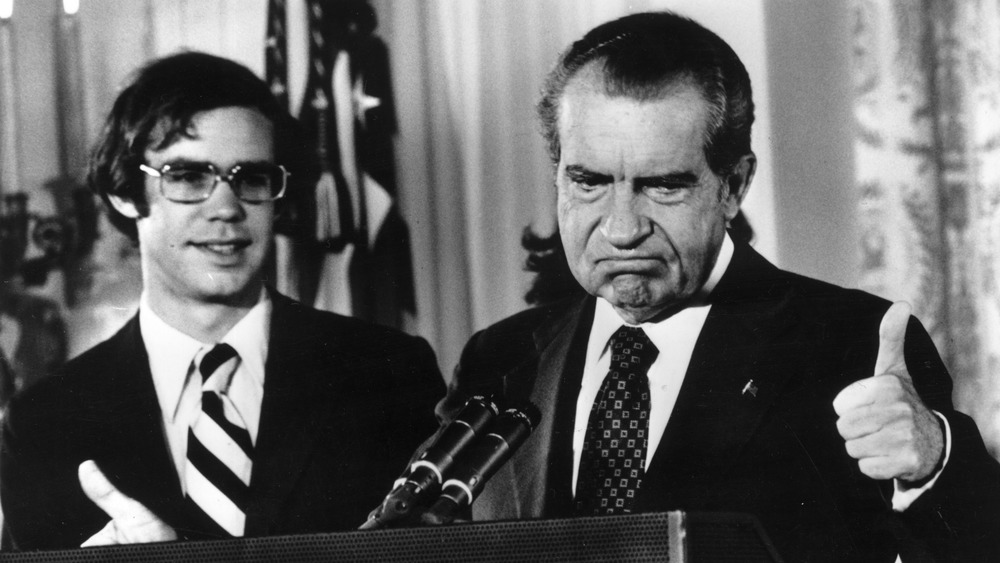

Nixon, though, wouldn't let it go. He hadn't been responsible for the original Indochinese policies, but he was caught in the aftermath. Hence, the decision that Ellsberg described as "signing his impeachment:" Watergate.

Carved into the legacy of Nixon and Watergate

President Nixon, as the University of Virginia outlines, was concerned to the point of obsession about how the policymaking of previous administrations affected him and his reputation, especially because he was up for reelection in 1972. Nixon had a "plumber" – a former CIA operative – break into Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office to find documents that would discredit Ellsberg, as Vox explains. Nixon also had a team of four break into the DNC's Watergate headquarters to steal and destroy documents, as well as place wiretaps, per History. They were caught on June 17, the day before The Post broke its story.

This incident led to a massive cover-up on the part of the Nixon administration regarding an entire bevy of illegal activities to try and ensure Nixon's reelection, which led to his impeachment in 1973 and resignation in 1974. The Pentagon Papers weren't the only reason this happened, but they were a key one.

At present, the story of the Pentagon Papers and all those involved has had historical, lasting ramifications on the role of free speech in a democratic society. As the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) succinctly said in defense of The Times in 1971, "If the government's vague and broad test of 'information detrimental to the national security' is accepted, there would be virtually no limit to censorship of the news now or by future administrations."

The Pentagon Papers have since been posted in full at the National Archives online.