The Crazy Real-Life Story Of The Man Who Wanted To Talk To Dolphins

Most people are pretty familiar with the idea that dolphins are incredibly intelligent, and one of the big reasons we know that is the work of John C. Lilly. Lilly was a neurophysiologist who was convinced that we could learn to communicate with dolphins — and believed they'd have a ton of interesting stuff to say — if only we could get over the language barrier, so that's what he tried to do with a massive experiment funded in part by NASA. Why NASA? It's complicated, but it turns out that just because you've got a fancy job, that doesn't mean you're too cynical to want to talk to dolphins.

That only tells a very small part of this strange tale. Lilly was always a little unique in the way he went about his studies on the mind and consciousness, and let's just say that once he started dabbling in LSD and horse tranquilizers, things really started to go off the rails.

Studying the brain and the consciousness within it is understandably difficult, but Lilly's studies took him from the neurons, pathways, and sections of the brain right out into other dimensions and into a belief in otherworldly cosmic entities. And that's not even the weirdest part of the story.

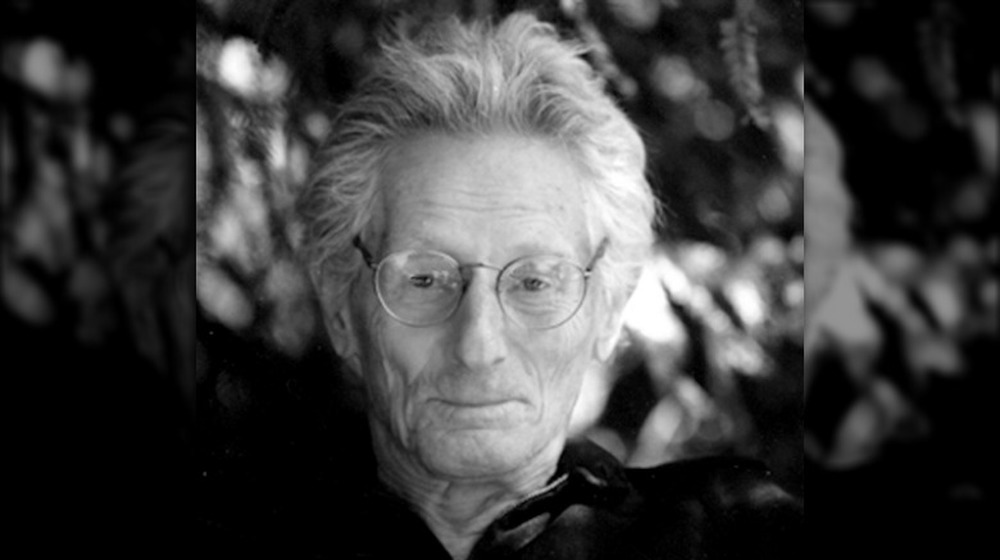

John C. Lilly: The early years

John C. Lilly was born in 1915, with the proverbial "silver spoon" — his parents were incredibly wealthy, and his father was the president of Minnesota's First National Bank of St. Paul. Lilly was also incredibly intelligent: The Penn Gazette says that by the time he was 16 he was bored to tears by his science classes, and turned to bigger things. He wrote: "How can the mind render itself sufficiently objective to study itself?"

That was a bit of hardcore foreshadowing into his life's work, and there's a few other incidents worth mentioning that will make sense later in life. Lilly was a senior at Caltech when his father was in a major car accident, plunging 100 feet off an embankment. He was in a coma for three weeks but survived, and the nagging knowledge of just how unlikely that was formed the basis for a lifelong belief that there was something else out there... which would both guide his later work, and eventually get really freaky.

Lilly graduated in 1942, was invited to join the University of Pennsylvania, and spent the war years in the cockpit of experiments that tested the effects of "explosive decompression" on pilots. Afterwards — and after trying to get his father to fund his so-called "bavatron," a machine he'd designed for reading the electrical activity in a rabbit's brain — he headed to the National Institutes of Health where The Guardian says he started experimenting on the brains of living creatures.

Pleasure, pain, and control

John C. Lilly's work at the National institutes of Health was nothing short of ground-breaking. According to The Guardian, he started by developing methods for inserting probes into and artificially stimulating the brains of living, awake, and aware monkeys (and cats) without causing major trauma or damage. That allowed him to pinpoint which areas of the brain were linked to feelings of pain and pleasure, and here's where it starts to get weird.

It was about the same time that the Cold War was getting into full swing, and the concept of brainwashing was starting to become a terrifying thing. Lilly used his newfound knowledge to directly reward and punish the animals he was working with to see whether or not it was a viable method of behavior modification, and according to his writings (via Sage Journals), he totally believed it was. Lilly wrote that developing his experiments into full-blown programs could allow for the discovery of "master-slave controls directly of one brain over another." He believed it could lead to total control — thoughts, motivations, consciousness, and actions.

The military absolutely got interested in what Lilly was doing, but historians say that it's unclear just how much they were involved in Lilly's work. What they do know is that Lilly claimed to be able to "intervene upon and manipulate the mind," which is some terrifying stuff straight out of Cold War fears.

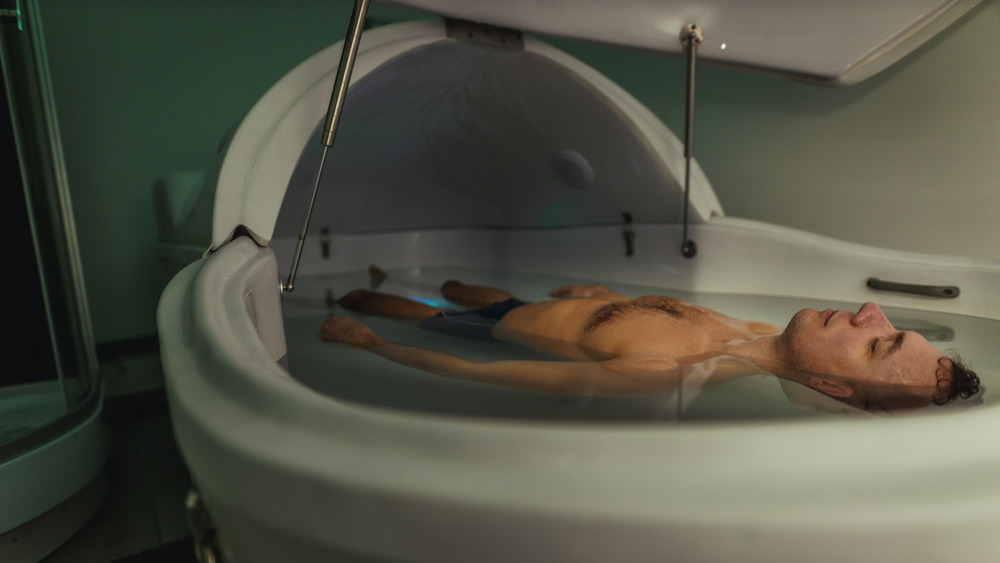

Mind control and the isolation tank

According to the research compiled in Sage Journals, John C. Lilly was at McGill when he first saw researchers conducting experiments on sensory deprivation. Volunteers were put into a room designed to minimize all sensory perception for as long as three days at a time, all with the end goal of finding out if it made them more suggestible. Lilly was pretty sure he could do better.

Lilly — still at the National Institutes of Mental Health — built the sensory deprivation tank, and he described it (via Omni) as a "black hole in psychophysical space, a psychological freefall," in which a person might find themselves delving into waking dreams or even out-of-body experiences. That started in 1954, and later, when he took some LSD and hopped into the tank, it was a very different experience filled with sensations of interstellar to intercellular travel.

Lilly's colleagues also believed that the tank was for more than just experiencing dreamlike hallucinations, and in 1956, the then-director of the NIMH talked to Congress about their experiments. The idea was that a person left in an isolation tank for long enough would be so disoriented that they could essentially be reprogrammed with whatever "information you want this individual to have." He continued, "[...] you can break anybody with this." The resulting PR nightmare was bad enough that Lilly went back to promoting the tank as a tool for introspection, not brainwashing.

Dolphin communication and... other stuff

john C. Lilly's time in the isolation tank made him wonder not just about the things that he saw, but about the brains that spent their entire lives floating in water. That, says The Penn Gazette, opened the door to the dolphin research, and there were a few things he was trying to figure out. For starters, did dolphins have a mind in the same way humans have a mind? Lilly, says The Guardian, was convinced that they likely did.

Starting with the desire to bridge the communication gap between human and dolphin, Lilly secured some funding through NASA and in 1963, he set up a facility in the Caribbean. It was home to three dolphins — Peter, Sissy, and Pamela — and it was soon also home to a woman named Margaret Howe Lovatt, who quickly volunteered to live with the dolphins. She began spending 24 hours a day, 6 days a week with Peter in order to find out what made Peter, well, Peter.

It turns out that a lot of what made the young boy dolphin tick was being pleasured... ultimately, by Lovatt, who decided it took too long to keep returning him to the company of the female dolphins. She never did get him to speak (and said that he had trouble with the letter M), but once word got out that she was providing Peter a service usually reserved for lady dolphins, that was the beginning of the end for the experiment.

The LSD experiments

The movie Flipper was directed by a man named Ivan Tors, and strangely, it was his wife who introduced John C. Lilly to LSD at a party. Fast forward not far at all, says The Guardian, and Lilly was combining dolphins and drugs in an entirely different way: he started giving it to them.

At the time, Lilly was one of a handful of people licensed to conduct medical research on LSD. It was believed that it might be of some help to patients diagnosed with various mental illnesses, but Lilly wanted to know what it would do to the big, perpetually floating brains of dolphins. Just what happened when he dosed dolphins Sissy and Pamela with LSD, well, it's not precisely clear. Lovatt recalled that it really didn't do much of anything, and the vet on site at the Caribbean research facility, Andy Williamson, put it this way: "Different species react to different pharmaceuticals in different ways." Makes sense, right?

But according to Vice, Lilly did notice a difference in the dolphins' behavior. He claimed that dolphins on LSD became very, very chatty for hours on end, and when he dosed another dolphin — one that was suffering from the fear and trauma that came after being shot with a spear gun — he found it made them more trusting as well. The experiments were complicated: unethical and not really scientific on one hand, but they're also the reason dolphins are recognized today as intelligent, thinking creatures.

John C Lilly's belief in brain size, intelligence, and communication

Lilly was convinced that he'd determined exactly what made a creature smart: brain size. The bigger the brain, he believed, the smarter the creature. To that end, he told Omni, "The highest intelligence on the planet probably exists in a sperm whale, who has a ten-thousand-gram brain, six times larger than ours. I'm convinced that intelligence is a function of absolute brain size."

He went on to say that a small body wasn't capable of sustaining a large brain (and, by extension, a high intelligence) because it wasn't suited to properly protecting a big brain from damage.

So, where does that leave people? We tend to think we're pretty smart, after all — we did invent Netflix, and that has to count for something, right? Lilly said that people only think they're the smartest creatures on the planet because they're incapable of communicating with other creatures in the same way we communicate with other humans, and that's some food for thought.

What happened to John C. Lilly's dolphins?

Sorry, this isn't a happy ending. Margaret Howe Lovatt said (via The Guardian) that by about 1966, John C. Lilly was getting less interested in teaching a dolphin to talk and more interested in the effects of LSD. Lovatt and her dolphin friend, Peter, were getting to the end of what was supposed to be a 6-month experiment of living together, and not only had lab director Gregory Bateson left, but so had the funding. With no funding, there could be no lab.

Lovatt found herself packing up the lab, including the dolphins. They were shipped off to a holding facility set up in an abandoned bank, where they were kept in smaller tanks. Peter, in particular, didn't take it well. Just a few weeks later, Lovatt recalled, "I got that phone call from John Lilly. John called me himself to tell me. He said Peter had committed suicide."

Ric O'Barry is part of the Dolphin Project, an organization dedicated to stopping the exploitation and slaughter of dolphins. He says the use of the term "suicide" is accurate, explaining: "Dolphins are not automatic air-breathers like we are. ... If life becomes too unbearable, the dolphins just take a breath and they sink to the bottom. They don't take the next breath." Andy Williamson, Lilly's vet-on-call, put Peter's cause of death at a broken heart.

Ketamine and the discovery of extraterrestrials

Medical News Today says that ketamine has been approved as an anesthetic in official hospital settings, but that's not what John C. Lilly had in mind when he started taking it. According to The Penn Gazette, he originally started taking it in hopes of alleviating the chronic migraines he'd suffered since childhood, but it didn't go as planned. After a three-week-long binge where he injected the drug on an hourly basis, friends intervened and had him committed to a psychiatric hospital. Interviews were done, observations were made, and he was eventually released — after promising to stop taking the drug.

He didn't: Omni says he preferred to call it "vitamin K," and what followed during his ketamine trips was more than mind-altering. Lilly explained: "On vitamin K, I have experienced states in which I can contact the creators of the universe, as well as the local creative controllers." Not one to squander an opportunity like that, Lilly added that he had asked them, "What's your major program?" to which they responded, "To make you guys evolve to the next levels, to teach you, to kick you in the pants when necessary."

He went on to say that he had experienced other realities he called "Alternity," and that he had learned to "tune" his "internal eyes" — and he had hopes that someday, someone would create a movie camera that would allow people to record and play back what was happening in these other realities: "an alternate-reality camera."

The Earth Coincidence Control Office

Lilly came to believe that he had inside information on just who was running the universe: for starters, there was the Cosmic Control Center (CCC) that was in charge of everything, and a Galactic Coincidence Control (GCC) that acted as a "substation." Within that was the Solar System Control Unit (SSCU), and immediately involved with our lives is the Earth Coincidence Control Center (ECCO).

The Penn Gazette says that he had become obsessed with the number of coincidences that he'd experienced, including ones that he credited with saving his life multiple times. He explained those coincidences with the belief that our lives are essentially a series of events caused by the ECCO and designed to guide us along a certain path to certain goals. Anyone wanting to become a "member of ECCO's earthside corps of controlled coincidence workers" could, as long as you took responsibility for what you did following the coincidences, and accepted the fact that once the ECCO no longer needed you, you'd be removed from the planet.

The ECCO was, he said, sort of a good-to-benign sort of entity, wasn't the only force out there, and had passed along this motto of the GCC: "Cosmic Love is absolutely Ruthless and Highly Indifferent: it teaches its lessons whether you like/dislike them or not."

Here's why alternate realities are a thing

In an interview with Omni, John C. Lilly talked a little bit about how his discovery of alternate realities wasn't just a bit of fun — he claimed that there was an incredibly important purpose that he'd stumbled on.

First, he started by explaining "a satori of mind," which was a state of "constant influx of pleasure" and a "self-transcendence." There were different levels of satori, and he believed that if he could teach everyone how to "experience at least the lower levels of satori, there is hope that we won't blow up the planet."

And here's where he says the point of it all comes in. Alternate realities and other states of consciousness were "the only way to escape our brains' destructive programming," he believed. While we were all "connected to the divine" as babies, we got farther and farther away from that state as we aged out of diapers and into things like starting wars. By experiencing the other, alternate realities out there, Lilly believed people would learn that they had choices other than destruction.

Human activity as furthering the solid-state entity

John C. Lilly also took a crack at explaining why humans are so destructive. It doesn't make sense, after all: why on earth are people so determined to watch the world burn, when we still have to live here?

He said that the complete extermination of the human race was the goal of something he called the "solid state entity" (SSE), which was an alien intelligence made up of a massive, interconnected artificial intelligence that existed in computer form. The goal of the SSE is to replicate, and in order to do that, it needed to destroy humankind. Why? Because by the end of the 21st century, Lilly saw mankind living only in domes controlled by the SSE. By the 25th century, it would become more interested in looking for other life like it, and mankind was simply no longer important. Lilly wrote (via Sean Kerrigan) that other SSEs were trying to influence mankind to rely more and more on technology, and further the cause of this alien artificial intelligence.

According to Sage Journals, Lilly came to realize that the preservation of "advanced biocomputers" — like people, dolphins, and whales — was at risk. Mankind's relentless pursuit of whaling was one way that the SSEs were slowly eliminating their competition, and by the time the Watergate scandal hit, Lilly was convinced that high-ranking, high-profile people — like the US Attorney General Elliot Richardson — were among those being manipulated by the SSE.

John C. Lilly's death and a complicated legacy

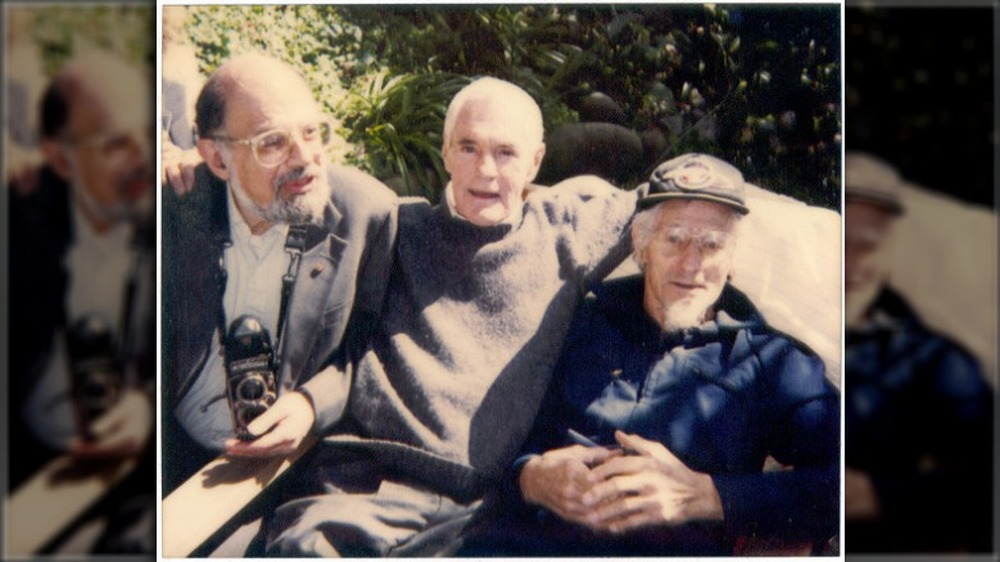

John C. Lilly (right, with Alan Ginsberg and Timothy Leary) died in 2001. The official cause of death, says the LA Times, was heart failure. He was 86-years-old, and he left behind a wildly complicated legacy.

At the same time he was one of the poster children for the counterculture of the 1960s, he was also one of the main reasons scientists accept the fact that species like dolphins have an intelligence that — while different from mankind's — is still conscious. Lilly had designed an entire computer system — Janus — that he had hoped would revolutionize our ability to speak to dolphins, and while that never quite worked out the way that he had planned, he did lay the groundwork for the countless researchers in animal intelligence that came after him.

There's still a catch, though, and it doesn't even have to do with the ECCO or an otherworldly sort of artificial intelligence. Lilly has long been a hero of conservationists, who claim he was firmly on their side when it came to things like keeping dolphins in the wild and protecting their habitats, instead of keeping them in captivity. But even up to just a few weeks before he died, some of his letters revealed that he had argued for keeping dolphins in oceanariums, in hopes that we'd eventually learn more about them. It turns out that it's not as clear-cut as conservationists may have hoped.

And, there's the whole alien alternate realities thing. He was a weird guy.