Ghost Army: World War II's Inflatable Army Explained

Every generation has their defining time, and for the so-called Greatest Generation, that was World War II.

It was Tom Brokaw who came up with the name for the generation of people born before 1924, and according to CNN, this was the generation forged in the fires of the Great Depression. They were the ones that went on to fight on the front lines of World War II and hold down the homefront. They saw terrible things — from serial killers to child soldiers and the liberation of the concentration camps — and for a long time, they just didn't talk about what they had seen and done. They just got on with it.

The chance to hear their stories is fading fast. According to The National World War II Museum, only 325,574 WWII veterans were still alive in 2020 (16 million served).

And that includes stories like the tale of the Ghost Army. They were a group of just a few hundred men tasked with using things like artistic ability, some creativity, and a literal ton of chutzpah to mislead Axis commanders and change the course of entire battles by making them believe just a handful of men were scores of them. They were forbidden from talking about their straight-from-the-movies tactics (and yes, there were inflatable tanks) for decades, but fortunately, the story of the super-secretive, super-brave group of men who saved tens of thousands of lives has come to light.

Who were the members of the Ghost Army?

The National WWII Museum calls them "The Combat Con Artists of World War II," and that's an incredibly apt description. They were more properly known as the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, and when they were deployed, a whopping 30,000 men were sent into the field and into combat. Sort of.

The unit — also called the Ghost Army — was made up of just 82 officers and 1,023 men. Using a whole arsenal of deception tactics, they were able to set up in the field and successfully mimic a large-scale deployment of two full divisions. Over the course of the war, they were used in 22 missions — often right on the front lines — to try to fool the Axis powers into thinking there were way more troops in particular areas than there actually were. And they did — according to the Smithsonian, their trickery and illusions were never discovered, even other Allied soldiers didn't know they even existed, and they saved an estimated 15,000 to 30,000 lives.

Who, then, were they? The men of the Ghost Army were hand-picked for their role, and many were plucked from art schools in Philadelphia and New York. Their ranks were made up of sound and theater technicians, illustrators and artists, and they all came with a seriously creative streak that would be life-saving.

A multimedia roadshow

According to the Smithsonian, the Ghost Army was actually made up of four separate units that each supplied a different component to the large-scale deception.

First, there was the visual component supplied by the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion Special. They were the ones building, inflating, and moving not just inflatable tanks but inflatable trucks, Jeeps, and even artillery that — especially from the air — were indistinguishable from the real thing.

Then, there was the Signal Company Special, and they were the ones faking radio broadcasts to go along with the fake tanks. Radio broadcasts (using equipment like that pictured) only go so far, though, and that's where the 3132 Signal Service Company Special came in. They were the ones recording and playing ambient noises — the sound of engines, the whir of machinery, and the background chatter that comes when 30,000 soldiers and all their gear move through an area.

And finally, there was the 406th Engineer Combat Company Special. They were the ones that lent a hand with getting everything up and in place, demolition, and security for the rest of the crew. There were 168 men in that part of the Ghost Army, and that's even more insane when you add in the fact that many times, their missions were surrounded by very real armies.

A Hollywood heartthrob goes to war

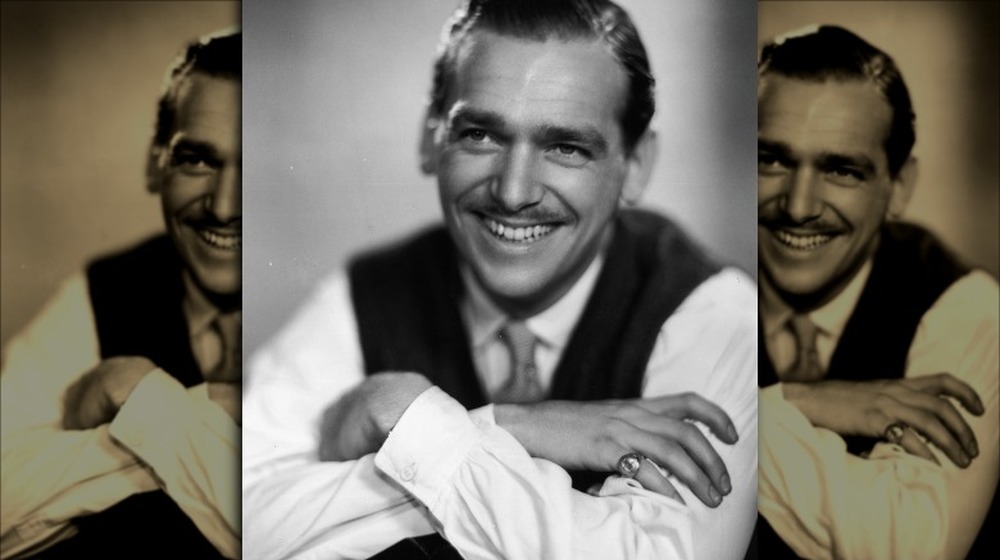

World War II's Ghost Army might seem like the stuff of fiction, and there's a good reason for that. According to Cabinet, the origins of the Ghost Army are about as unlikely as unlikely can be — they go all the way back to Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (pictured).

Fairbanks was the era's Hollywood royalty. Not only does he have scores of credits to his name, but his father does, too. Fans of classic cinema would recognize Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., as having played famous faces like Zorro, Robin Hood, and D'Artagnan in The Iron Mask.

It was fitting, then, that Fairbanks Jr. was the one that first pitched the idea of using deception — and artistry, if you will — on the battlefield. It wasn't an original idea, and it was something he'd picked up from an old family friend who just happened to be Lord Louis Mountbatten. Mountbatten had spilled the beans to him about a top secret British unit that was experimenting with things like broadcasting the sound of troops behind smoke screens, and the idea stuck.

With Fairbanks, Jr., at least. Others in the military weren't so keen on the idea and saw the kind of deception he was talking about as less than honorable. Still, the noted actor found support with Hilton Howell Railey — the man behind Amelia Earhart, Antarctic expeditions, and an attempt to recover the Lusitania — and they proved just how effective deception could be.

Ghost Army hones their craft on American soil

It's an old saying that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and that's true with the Ghost Army. Alone, they may have had questionable success. Together, though, they fooled some of the top minds of the Axis military — and they practiced on their home soil.

The Smithsonian says they got their training at Fort Meade, and that included learning the basic art of camouflage. Then, they were put right to work — it was the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion Special that was told to make an aircraft factory disappear.

It was a large-scale magic trick done for a very good reason. According to Ghost Army, there was a very real fear that German forces would strike on the mainland United States, with military installations and factories deemed the most likely targets.

Enter the 603rd. They were sent to Middle River, Md., and were tasked with making the Glenn L. Martin aircraft factory (which built the bomber pictured) disappear. Sounds unlikely? They absolutely did it by strategically covering parts of the compound with camouflage netting and painting other parts so that from the air, it would look like the factory was simply part of the countryside. It wasn't long after they finished in Maryland that they were assigned to the Ghost Army and sent off to Europe to work their magic.

The guys on the radio

Sound was an incredibly important part of what made the Ghost Army effective, and getting it right was no small endeavor. It started with Bell Labs, who created "firing tables" that allowed the techs to essentially aim their broadcasts to carry exactly where they wanted them to go. Then, the actual sounds were recorded at Fort Knox, and they had to have a wide variety of effects. It wasn't enough just to record a tank — they needed to record tanks on level ground, uphill, downhill... because to the trained ears they were trying to fool, those scenarios all sound very different.

According to Task & Purpose, they recorded everything imaginable, right down to soldiers talking. That was the background, and front and center were the radio operators.

They weren't just any radio guys, though. When the actual military unit moved out and the Ghost Army stepped into their shoes to make the enemy believe the actual unit was still in place, the transition needed to be flawless. That meant radio operators who could study other operators and the way they communicated — particularly through Morse code — and then imitate their style.

Sgt. Stanley Nance explained their job this way (to Ghost Army) — "Could I have sent just one radio message that changed the tide of battle, where one mother, or one new bride was spared the agony of putting a gold star in their front window? That's what the 23rd Headquarters was all about."

Were they really using inflatable tanks?

The idea of inflatable tanks sounds like something out of Hogan's Heroes instead of actual history, but it's 100 percent true.

According to Ghost Army, the 23rd Headquarters had hundreds of inflatable tanks (like the one pictured) that they deployed to give the illusion that an area was occupied by actual functional, fighting troops. The tanks were constructed over a lightweight frame of inflatable tubes, then the skin of the tank was stretched over the frame. They were about 18-feet long, more than 8-feet wide, and stood almost 8-feet tall to the top of the turret (which was assembled as a separate piece). It took just around 20 minutes to get a single tank inflated from inside a canvas bag to sitting in position — a process usually done beneath the cover afforded by camouflage netting.

While the tanks were the most famous of the Ghost Army's props, Task & Purpose notes that there were other inflatables, too — like planes and pieces of artillery. In addition to setting up this inflatable army, other Ghost Army members participated in another kind of deception that developed as the war went on. Soldiers — usually part of the 406th Combat Engineers Company — would fake unit patches and insignias, then head into town for a few drinks. There, they'd get chatty with the locals, spreading the exact kind of misinformation that they wanted German spies and informants to hear.

Operation Bettembourg

The Ghost Army's first success was Operation Bettembourg. According to the Ghost Army Legacy Project, it was Sept. 14, 1944, when they were summoned to coordinates along the Moselle River. They were being called in to complement Gen. George Patton's Third Army and reinforce a 25-mile stretch of Allied front line that was lightly held and presenting a massive weak spot.

The Ghost Army was tasked with two objectives — first, the 500 men stationed there would give the appearance that there were actually two fully outfitted units of 8,000 holding the sector, and secondly, they were going to draw as many German units away from Metz as they could.

Between 10 p.m. and midnight on September 15, the sound crews broadcast recordings of tanks moving in, and inflatables were up that same night. By the following evening, fake radio broadcasts were being bounced around between Ghost Army operators and nearby — real — units, and in the meantime, 6th Armored markings had been painted on the tanks, and patches were made. Soldiers headed into town to chat with locals about their division, trucks made it a point to be seen gathering water — enough for 8,000 men — and civilians asking questions were given answers they wanted the Germans to hear.

German patrols moved to within just a few miles of the Ghost Army, and it wasn't until September 22 that the 83rd Infantry arrived to take their position. They played the sound of their tanks rolling out, and no one ever caught on.

Operation Brest

In August of 1944, the Ghost Army headed to Brest — the German-held port city was under Allied siege, and it was a strategically important location — they needed a port to bring in supplies for the troops funneling in through Normandy.

There were three American divisions stationed there... and the Ghost Army. The Ghost Army Legacy Project says they stepped in to the very active combat zone to impersonate two 6th Armored Division tank battalions with inflatables (like the one pictured), who had actually withdrawn from the area and been moved elsewhere.

The Ghost Army was split into three "task forces." X was made up of 200 men who needed to fool the German commanders into thinking they were not only holding a perimeter but moving into place in preparation for an attack. Task Force Z — made up of just 160 — also impersonated an entire tank battalion, moving into position near Milizac.

And Task Force Y had perhaps the most terrifying job of all — draw artillery fire away from the other troops. They used flash canisters psyched with the sounds of fire, and it worked. At the same time the actual artillery battery shelling the German army got no return fire whatsoever, Cpl. Rolff Campbell wrote, "All hell seemed to be hurtling through the air."

The Ghost Army's sister division

The Ghost Army wasn't the only American unit relying heavily on subterfuge, deception, and some serious creativity to help win the war. While they were impersonating tank and artillery battalions, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. had another unit in the works. They were the Beach Jumpers, and they were doing the same thing at sea.

According to HistoryNet, the Beach Jumpers worked in small units that were formed around 63-foot "crash boats," or Air-Sea Rescue (ASR) boats (pictured). On board was specially designed equipment that allowed them to broadcast sounds that mimicked an entire invasion fleet, along with Roman candles (to simulate gun fire) and smoke generators.

When it came time to jump into the action, it was a trial by fire. BJU-1 was deployed during Operation Husky, the Allies' attempts at invading and taking Sicily. Bad weather delayed their first mission, but on their second outing, they successfully convinced German troops to engage with an invasion fleet that wasn't there. Their success elevated them to the front lives, and they went on to participate in invasions along the Italian coast.

The Ghost Army was a secret for a long, long time

For decades, few people knew about one of the most unlikely stories of World War II. That's because the existence of the Ghost Army was officially classified until 1996 — but, that's not to say word didn't get out about them.

According to the Ghost Army Legacy Project, some stories made it out into the public — starting with the story of Sebastian Messina. He was a member of the Signal Company Special and was interviewed by a local paper when he went home on leave in the summer of 1945. Even though the paper had submitted the story to the censors at the War Department and it had been squashed, once the war ended, the paper ran the story anyway.

After a flurry of activity, the Pentagon got involved and put an end to that sort of chatter — and the Ghost Army faded back into the shadows.

There were a few other mentions of the unit that popped up from time to time, too. Fred Fox freelanced for The New York Times, and when he did write a first-hand account of the Battle of the Bulge, he hinted at what his unit had really done, without coming right out and saying it. (Fox also fought for years to get the whole thing declassified.) Another article appeared in the Smithsonian magazine in 1985, but it would be a while before the members of the Ghost Army could make their story widely known.

After the war: the men of the Ghost Army

When the war ended, there were a number of Ghost Army men who went on to major careers in both the art and fashion worlds — and many used their talents to sketch some incredible works of art depicting the scenes they saw while on the front lines in Europe.

Those are men like Ellsworth Kelly (pictured), who The Art Story names as one of the most influential artists of the post-war era. Bill Blass became a fashion designer whose clothes were worn by the post-war upper-class (via CFDA), and Arthur Singer's work is widely recognizable — he was one of the country's most prolific and popular bird painters.

And then, there's Gilbert Seltzer. NPR says that he enlisted when he was 26 years old, and the architectural draftsman almost immediately found himself at the head of a platoon within the Ghost Army. In 2019, the then 104-year-old veteran sat down with his granddaughter for an interview about his time in the Ghost Army and reminisced about setting up some fake guns in the fields of a French farmer. After telling the understandably irate farmer what they were doing, he said, "In four syllables, [he] described the mission of our outfit." Those four syllables were, "Boom boom! Ha ha!"

Later that year, Patch reported on his 105th birthday — spent hard at work in the office at his Gilbert L. Seltzer Associates architectural firm, where he was still drawing all his plans and blueprints by hand.

They weren't the only ones using some serious trickery

The Americans and their top secret units weren't the only ones using some sneaky methods to try to save lives, and D-Day actually started with a bit of British deception.

According to Atlas Obscura, even as the planned invasion fleet gathered and waited for the signal to converge on the beaches of Normandy, the D-Day operations started with Operation Titanic, located at three separate drop zones each chosen to give the illusion of the beginning of a full-scale invasion... well away from the actual targets.

On June 5/6, 1944, several hundred dummies — dressed in complete paratrooper uniforms — were dropped alongside a handful of very real soldiers of the British Special Air Service, who provided special effects in the form of flashes, the release of chemicals to simulate the smell of artillery shells, and sound effects. The dummies — which were all named Rupert — were designed to self-destruct on landing, to make sure the deception wasn't discovered until well after the actual invasion was underway.