Inside The Time When Actual 'Fake News' Helped Fuel A War

Fake news may seems like a 21st century phenomenon, considering how often Donald Trump uses the term to delegitimize any and all criticism of the way he has served as president. According to Washingtonian, he even erroneously claimed to have invented the term himself and is "very proud of it," but the popularization of the term has actually been attributed to Craig Silverman, a media editor for BuzzFeed News, who used the term to describe the spread of online misinformation for a 2014 research project. Consult the U.S. Office of the Historian, however, and you'll find that the practice of publishing false information to sway public opinion in the United States has a much longer history than you may have previously thought. Fake news actually dates back to the late 19th century, but back then it went by a different name: yellow journalism.

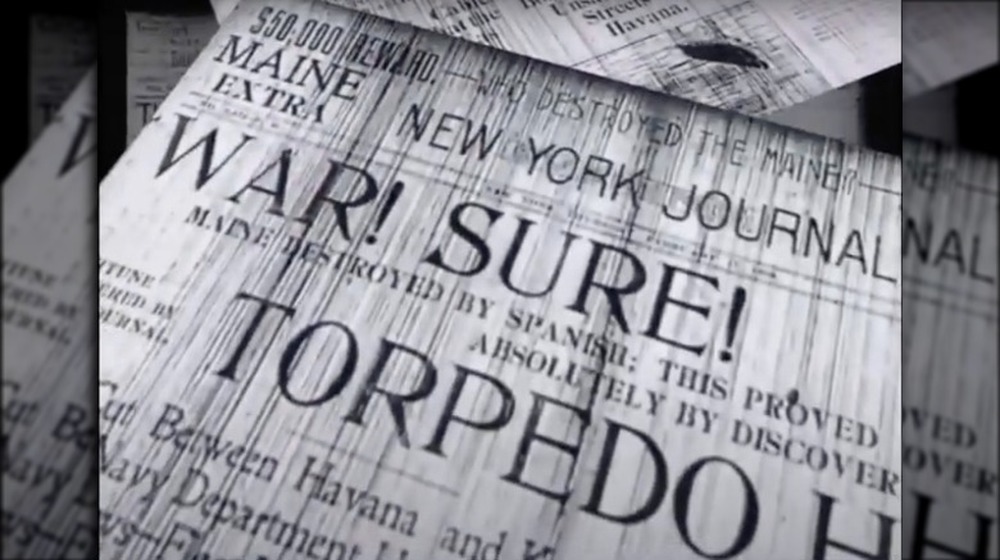

This sensationalized form of reporting favored juicy headlines and graphic imagery over empirical evidence and straightforward, objective coverage. At its peak in the 1890s, it would end up fueling the flames of a conflict that ultimately erupted into the Spanish-American War, which was fought in Cuba and the Philippines and resulted in the United States significantly increasing the number of islands it has stolen. Let's take a look at the origins of yellow journalism and how it laid the basis for the fake news of the 21st century.

The New York City newspaper fake news showdown

Toward the end of the 19th century, newspaper magnates Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolf Hearst had a bitter feud to sell papers. And Pulitzer had quite the contender in his corner, though it had nothing to do with headlines. His New York World printed a comic strip drawn by Richard F. Outcault called "Hogan's Alley." Printed in full color, the cartoon about life in the city's slums was a huge hit, and its most popular character was known as the Yellow Kid. Pulitzer largely had the Yellow Kid to thank for the sizable increase in sales of the World.

Hearst wanted in on the action. So in 1896, he started a bidding war with Pulitzer for the cartoonist, and won it. Heart successfully poached Outcault from Pulitzer. The publishers' fight over the rights to publish the Yellow Kid coined the term "yellow journalism."

After that, the term came to be used for the vicious battle to sell newspapers via sensationalist — and yes, sometimes false — coverage of current events. The hot-button issue of the time was the unrest in Cuba, in those days still a colony of Spain. Guerrilla fighters there had been pushing for independence for decades, and the struggle intensified in the 1890s. Pulitzer and Hearst latched onto the conflict to increase sales, using lurid headlines and vivid drawings to highlight the ruthlessness of Spain's crackdown, even going to far as to print what we today would call fake news.

Pulitzer and Hearst's fake news helped spark the Spanish-American War

By 1898, Pulitzer and Hearst's yellow journalism war had garnered significant public opinion in favor of the United States going to war with Spain. Hearst got his hands on one of the juiciest pieces of news in the media war in February of that year, according to the Library of Congress. He came into possession of a letter written by Spanish Minister Enrique Dupuy de Lôme from December 1987 in which he criticized then-U.S. President-elect William McKinley as indecisive, and said that negotiations with the Cuban rebels were futile. In what may be the epitome of yellow journalism, Hearst's New York Journal printed an English translation of the letter on February 9 with the headline, "The Worst Insult to the United States in Its History." (Sound familiar?)

When a U.S. naval ship sank in Havana Harbor the following week, both papers jumped on the chance to blame Spanish conspirators. And when a Navy Court investigation concluded that a mine had been the cause, both publications called for war.

Although yellow journalism had a hand in the U.S. going to war with Spain (Hearst was famously quoted as telling an artist sent to cover the conflict, "You furnish the pictures, I'll provide the war!"), it wasn't the sole factor that led to the conflict. As History.com has noted, a 1976 Navy investigation found that the explosion was most likely the result of a fire on the ship that ignited the ammunition stocks on board.