Why Did We Fight The Spanish-American War?

In the 16th century, Spain began extending its empire in the Americas. At its peak, it controlled lands from as far north as Virginia down to the Argentinian province of Tierra del Fuego, on the southernmost tip of South America (excluding Brazil, which was Portuguese), and westward as a far as California and even Alaska. By the 19th century, however, Spain had lost the vast majority of its colonies to independence movements. According to the British Library, countries from Mexico to Costa Rica to Colombia, Chile, and Argentina had all gained independence by 1821. By the end of the 19th century, the only Spanish colonial remnants in the Americas were Cuba and Puerto Rico. Aside from these two islands, Spain's only other imperial holdouts in the Western Hemisphere were in the Philippines, Guam, and the Northern Mariana, Marshall, and Carolina Islands in Micronesia. By the dawn of the 20th century, it had lost them all.

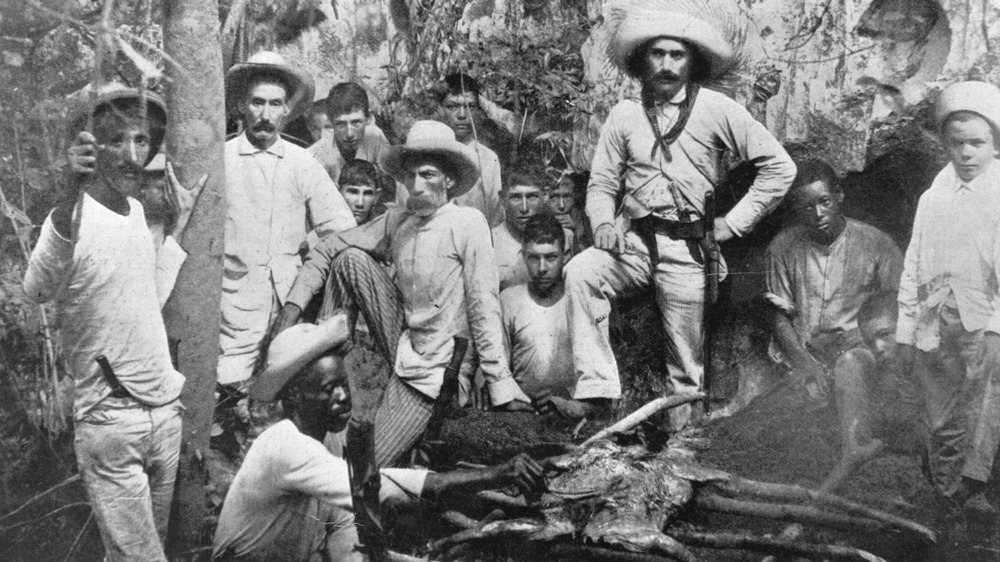

As noted by the Library of Congress, trouble began brewing for Spain in Cuba in 1868, when guerrilla fighters called mambises began a campaign for independence. Their struggled ended with a treaty that wasn't honored, and by the 1890s, the fight for Cuban independence was back on. Led by the poet José Martí, who died during the first few weeks of the armed conflict that ensued, this second crack at gaining autonomy set the stage for the Spanish-American war.

Political dissent in Puerto Rico and unrest in the Philippines

In the last two decades of the 19th century, the push for Puerto Rican independence manifested in the formation of several political parties that campaigned for a break from Spain in one way or another. Some advocated for independence, while others espoused an alliance with the United States. In November 1897, pressure from the United States led Spain to grant Puerto Rico autonomy, and a new government was installed when news finally made it to the island the following year.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, José Rizal was leading a movement that challenged Spanish authority. After studying in Madrid and writing seditious novels during his travels through Europe in the 1880s, he returned to Manila and founded a peaceful political movement called the Liga Filipina, for which he was promptly exiled to the island of Mindanao. During his exile, a man named Andrés Bonifacio started up a secret society called Katipunan, which pushed for the violent overthrow of the Spanish colonizers. He issued a call to arms on August 26, 1986 called the Grito de Balintawak, and was later betrayed and killed by his successor, Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy. In May 1897, Aguinaldo worked out a deal with the Spanish to be exiled to Hong Kong with a sum of 400,000 pesos, which he invested in weapons in order to continue his plight. Now all the situation needed was a catalyst to propel all of this unrest into all-out war.

The sinking of the USS Maine gives the United States cause to declare war with Spain

The Spanish employed increasingly violent tactics to try and quell the revolution in Cuba. Spanish General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau implemented a Reconcentration Policy that rounded up Cuban citizens and concentrated them in centralized locations in order to better control them. He also declared martial law across the entire island. According to History.com, this brutality was vividly portrayed in the U.S. media. Several newspapers engaged in yellow journalism (the original, and actual, fake news) to sensationalize the violence and drum up support for U.S. intervention in the conflict. The New York Journal published a copy of a letter in which the Spanish Foreign Minister harshly criticized President William McKinley. The catalyzing moment came when a ship sent to provide protection to U.S. and property in Havana, the USS Maine, blew up in Havana Harbor on February 15. An inquiry by the U.S. Naval Court found the cause to have been a Spanish mine, though a 1976 report lays the blame on a fire that ignited the ship's ammunition.

President McKinley ordered a blockade of Cuba on April 21. Spain declared war on the United States on the 24th. The United States declared it back the next day, then made the declaration retroactive to the 21st. The conflict lasted less than four months, but by the end, Spain had lost the last of its American colonies, and the U.S. had stolen a few more islands in its attempt to spread its own empire throughout the world.