The Crazy Story Of The Bone Wars Explained

Over the course of the 19th century, people around the world were fascinated by dinosaurs and their fossilized bones that kept popping up. But no one seemed more obsessed than American paleontologists Edward Cope and O.C. Marsh, and the rivalry between the two men became a stain on paleontology's history for decades after their deaths.

Although the two men are responsible for discovering and naming countless different types of dinosaurs and prehistoric animals, they're also responsible for destroying an unknowable amount of the fossil record. And they did this solely to keep the other one from getting it. And in the interest of putting out as much of their own research as possible, both men published research that would be riddled with errors. Some of their mistakes plagued paleontology for years,

Even without these men, it's likely that dinosaur fossils would have been discovered across the United States, and that the public would have been fascinated by them. But thanks to their competitive spirit, an innumerable amount of the fossil record was irrevocably destroyed. This is the crazy story of the Bone Wars explained.

Who was Edward Drinker Cope?

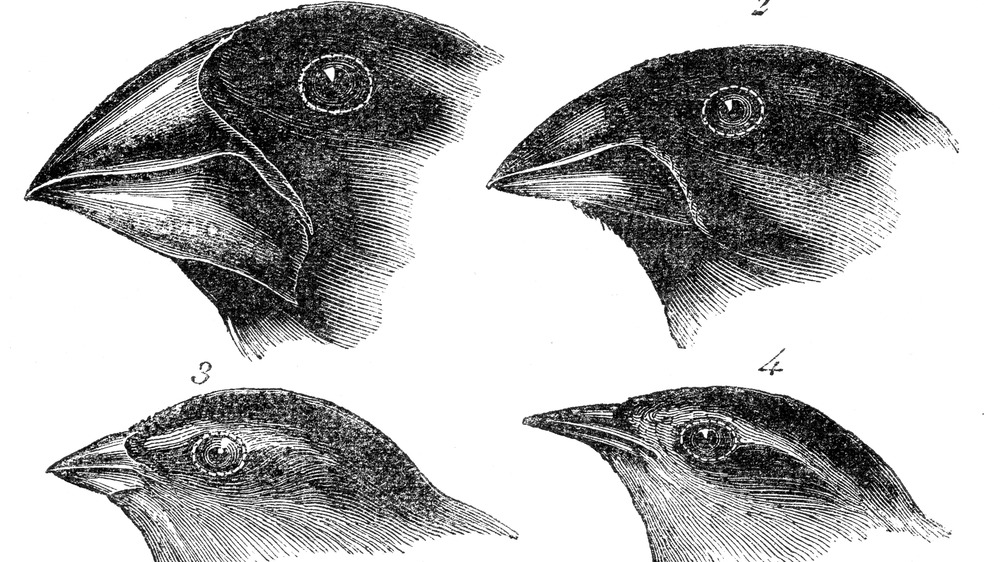

Born on July 28, 1840, American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope discovered almost 1,000 different extinct species during his career, according to Britannica. Studying evolution, Cope was one of the founders of the neo-Lamarckian school of thought, which suggested that species evolved based on acquired inheritances that were, to a certain degree, chosen.

According to the Smithsonian Institute Archives, Cope was born into a Philadelphian Quaker family and had his interest in the natural world piqued at a young age. After receiving an education at the University of Pennsylvania, Cope worked at the Academy of Natural Sciences, cataloguing the collection of amphibians and reptiles. Although his father had tried to encourage Cope to take up farming, "farm life further ignited Cope's interest in natural history," and eventually his father had relented and allowed Cope to pursue scientific investigation.

In 1863, Cope was sent to Europe by his father, allegedly to help him avoid the draft in addition to separating him from a love interest. While in Europe, Cope continued to study biology and made the acquaintance of several leading paleontologists and anatomists, one of whom was Othniel Charles Marsh. The two couldn't have been more different, despite their equally strong personalities. Cope didn't have a single degree, but he had already published 37 papers, starting in 1859 with a scientific paper on salamanders. Marsh meanwhile had two university degrees but not a single publication bore his name.

Who was Othniel Charles Marsh?

According to Britannica, Othniel Charles Marsh was born on Oct. 29, 1831, and made a name for himself as the first professor of vertebrate paleontology in the United States. He started teaching at Yale in 1866 and would continue to do so until his death in 1899. Marsh was also responsible for organizing the first Yale Scientific Expedition in 1870 and went on to sponsor similar expeditions almost every year afterwards. The expedition in 1870 was even responsible for discovering the first pterosaur outside of Europe.

According to the National Academy of Sciences, Marsh was known for both his "wealth and position," though most of it came from the fact that George Peabody was his uncle and was incredibly helpful with financing Marsh's career. However, despite organizing numerous expeditions, "Marsh himself spent only four seasons in the field, between 1870 and 1873," as per the University of California Museum of Paleontology.

"Using his inheritance from his uncle," Marsh collected hundreds of vertebrate fossil skeletons, fossil footprints, and other archeological artifacts, many of which can still be seen as of 2020 at Yale's Peabody Museum (via Museums of the World). In 1869, Marsh was also one of the first to declare the Cardiff Giant a hoax. Known as "America's Biggest Hoax," the Cardiff Giant was a block of gypsum that had been carved to look human and claimed to be a 10-foot tall petrified prehistoric man.

Amicable differences

Compared to Edward Cope's Lamarckian lens, O.C. Marsh was a firm supporter of Charles Darwin's theories of evolution, reports the National Academy of Sciences. However, the two initially had an amicable relationship. According to ThoughtCo, the two met in Berlin, Germany, in 1864, during which time western Europe was considered to be at the forefront of paleontological research. Though the two men didn't exactly get along and didn't consider the other to be a real scientist, they were cordial with one another.

Unfortunately, according to Science Focus, there are few records of their initial encounters, so not much is known about their early relationship. However, despite their differences and resentments, the two men engaged with one another to the point where in 1868, Cope invited Marsh to the marl pits in southern New Jersey, ostensibly to share the bounty of fossils to be had there. But while drama was about to start in the marl pits, the two men's relationship also came to a head over the fossilized skull of an Elasmosaurus.

The Elasmosaurus fossil

In 1868, Edward Cope reconstructed a fossil he received from Kansas, naming it Elasmosaurus, as per ThoughtCo. A large marine animal from the Cretaceous period, no one had ever seen an aquatic animal with these kinds of proportions. And unknowingly, in his reconstruction, Cope placed the skull of the Elasmosaurus on the vertebrae of its short tale rather than those of its long neck.

According to The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, O.C. Marsh initially pointed out that vertebrae were positioned backwards, and after being unable to come to an agreement the two men asked the academy curator Joseph Leidy to settle their argument. "Leidy promptly removed the head from one end and placed it on what Cope had thought was the tail."

The story goes that, having already published his findings, Cope went out and tried to purchase every copy of the journal where he'd published his error in order to destroy any trace of his error. To be fair, Marsh had also been wrong about the orientation of the vertebrae, but Cope was the one on record with his error.

And while it's definitely a great origin story for the rivalry, no one knows for sure whether or not this actually happened. But another incident in 1868 that definitely happened certainly sealed the fate of American paleontology.

The fossil site of the Hadrosaurus

That same year, O.C. Marsh took a trip to the Cretaceous marl pits of southern New Jersey. According to National Geographic, a partial skeleton of a Hadrosaurus had been found in the marl pits, and Edward Cope invited Marsh to southern New Jersey to check out the plethora of prehistoric fossils. But whether this invitation came out of a desire to boast or a desire to share, Cope soon found his life-long nemesis.

According to Science Focus, since miners regularly worked on the site and came across various fossils, "the affluent Cope didn't have to dig through the muck himself." Instead, he paid the miners to bring him the best specimens that they found. But not only could Marsh do the same, when he saw the potential of the fossil specimens, he bribed the miners "to send the bones north to his collection in New Haven rather than west to Cope's study in Philadelphia."

Cope was livid when he found out, and for the rest of their lives the two men sought every opportunity to criticize and discredit one another.

And the Bone Wars commence

As fossils started to be discovered in the American West in the 1870s, the Bone Wars officially commenced between Edward Cope and O.C. Marsh. And both Marsh and Cope were anxious to always be the first ones on the scene. According to ThoughtCo, in 1877, Arthur Lakes, a schoolteacher in Colorado, sent letters to both Cope and Marsh describing "saurian" fossils he'd discovered while hiking. Marsh promptly paid Lakes $100 to keep this find a secret, and when he found out that Lakes had already informed Cope of his discovery, he sent an agent west "to secure his claim." There were other fossil sites that Marsh tried to claim before Cope, but he wasn't always successful.

According to The Houston Museum of Natural Science, Cope also tried to steal fossil sites out from under Marsh at the same time. When Marsh got a letter from railroad workers at Como Bluff in Wyoming, Cope was soon sending his own diggers to the quarry. Although Cope wasn't entirely successful, he was able to steal some bones from the site. And once Marsh's payments started to get more and more erratic, "one of the railroad men began working for Cope instead."

A rivalry backed by Washington

As Edward Cope sought to prove he was a better scientist than O.C. Marsh, he rushed to publish any and all findings, "a practice paleontologist Bob Bakker calls 'taxonomic carpet-bombing.'" He published 76 papers between 1879 and 1880 alone, though this was a far cry from the 1,400 articles he would write during his lifetime.

In 1882, Marsh used his connections to become chief paleontologist of the U.S. Geological Survey, a brand new agency. According to the Smithsonian Institute Archives, Marsh held the position until 1892. With this position, not only did Marsh gain an immense amount of political power, but he also received control of federal funds. While these had initially been funds that both he and Cope had competed for, now Marsh had the ability to cut Cope off from federal funding completely, which he promptly did.

Although Cope tried to make up for his losses through a silver mining venture, he ended up losing everything. According to The Bone Sharp: The Life of Edward Drinker Cope, by Jane P. Davidson, by 1885, Cope had mortgaged his "laboratory-house" and leased his residence.

But then, in 1890, Marsh went a step too far. Claiming that Cope's fossils had been collected with federal funds and by extension belonged to the government, Marsh attempted to seize Cope's fossil collection. Cope was able to demonstrate how he'd paid for most of the fossil collection out of his own pocket relatively easily, but after this he was determined to annihilate Marsh's career.

Bone Wars hit the front page

O.C. Marsh hadn't been flying completely under the radar. In 1884, after Congress started investigating the U.S. Geological Society, Edward Cope got some of Marsh's employees to testify against him. But to Cope's dismay, none of this was reported in the newspapers at the time.

Fed up with Marsh, in 1890, Cope reached out to a freelance journalist at The New York Herald. Over the years, Cope had been keeping track of Marsh's malfeasances, ranging from scientific errors to felonies, and he handed it all over to the Herald. Although the Bone Wars had been contained to the scientific journals for quite some time, on Jan. 12, 1890, their dispute was aired to the public.

According to Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, by Wallace Stegner, the headline read, "SCIENTISTS WAGE BITTER WARFARE." "It is doubtful that any modern controversy among men of learned has generated more benom than this one did," writes Stegner. And these weren't just recent grievances. Cope's laundry list extended almost two decades. In the same newspaper, Marsh put out a rebuttal where he accused Cope of much of the same.

After the "public airing," Congress cut much of the funding for the agency and eliminated Marsh's department, "position, power, and most of his income." Cope's reputation was also damaged, and he struggled financially for the rest of his life.

A mountain of discoveries

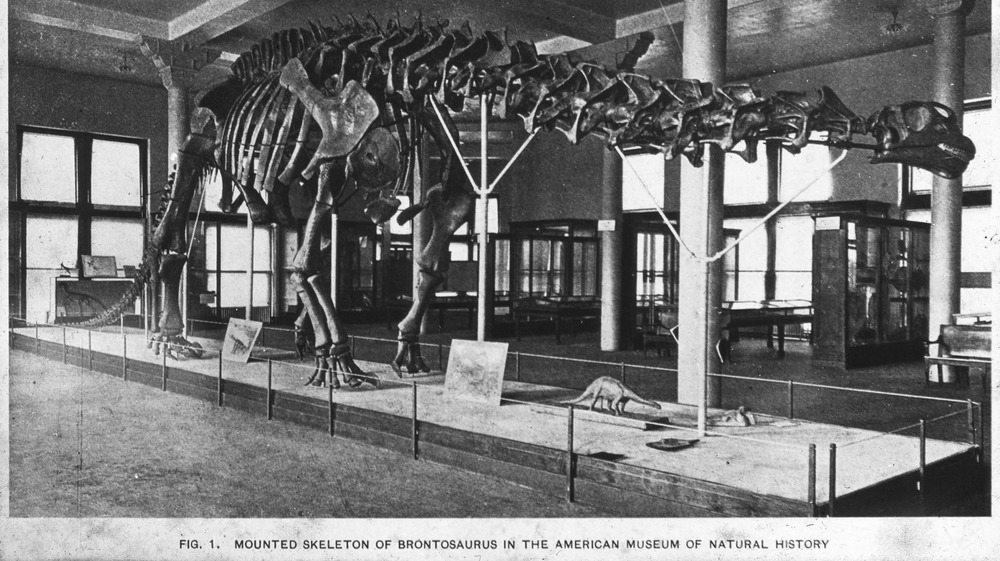

Despite the drama, the antics of these two men led to the discoveries of over 100 different new dinosaurs. According to ThoughtCo, Edward Cope discovered 56 new dinosaur genera and species, and O.C. Marsh discovered at least 80. Among the dinosaurs discovered include some of the first species of Diplodocus, Allosaurus, Triceratops, and Stegosaurus.

And both men left behind a staggeringly impressive collection, with Cope's alone estimated to contain almost 13,000 specimens, reports PBS. Meanwhile, at least 80 tons of Marsh's collection was acquired by the Smithsonian — after it was found that many of his fossils were in fact owned by the government — and the vast majority was left to the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale.

According to Science Focus, while Marsh and Cope were developing their own expertise, they were also responsible for hiring and training "those who would become the next generation of American paleontologists." The constant discovery of fossils by both Marsh and Cope were always accompanied by publicity, which "helped to feed the American public's increasing hunger for new dinosaurs." Marsh was also one of the first people to suggest that dinosaurs and birds shared an ancestral link.

Although people were always going to be fascinated by dinosaurs, the Bone Wars had a strong impact in shaping people's curiosity. However, the rivalry between the two men may have been just as harmful to scientific discovery as it was beneficial.

Riddled with errors

The work of the two men was constantly littered with errors, since they were more concerned with the quantity of their work rather than its quality. According to WTTW, the two men amassed countless mistakes, "such as confusing a younger version of one species for a new species altogether." It would take some time for the paleontologists after them to discern exactly was and was not a new species.

One of O.C. Marsh's mistakes remains up for debate today. After mistaking the skull of an Apatosaurus for a Camarasaurus, Marsh named another long-necked dinosaur "Brontosaurus," which many paleontologists now believe is just an Apatosaurus and claim that the "Brontosaurus" simply never existed. But thanks to Marsh's initial error, both dinosaur names continued to be used over the next century.

However, some paleontologists now believe that Marsh may have been onto something and are claiming that the Brontosaurus does in fact exist as a distinct dinosaur from Apatosaurus, and that these two are in fact separate genuses, according to National Geographic.

And an unknown amount of loss

In addition to metaphorically damaging paleontological research, the two men were responsible for quite a lot of literal damage and destruction. In the attempt to keep the other from discovering fossils, the two paleontologists engaged in a number of destructive activities, including deliberately destroying fossils and fossil sites. And in addition to stealing fossils outright, according to Slate, rival workers sometimes pelted one another with rocks or threatened each other with guns over the fossil sites.

According to Reprehensible, by Mikey Robins, both Edward Cope and O.C. Marsh also used dynamite to destroy parts of dig sites that they hadn't had a chance to get to so that the other "couldn't find anything left to plunder among the detritus when they left." Knowing this, it's impossible to estimate exactly how much was irreparably destroyed by both Marsh and Cope in their quest to out-do the other.

And according to ThoughtCo, European paleontologists were "horrified by the crude behavior of their American counterparts." And as a result, there was a "lingering, bitter distrust that took decades to dissipate."

The final challenge

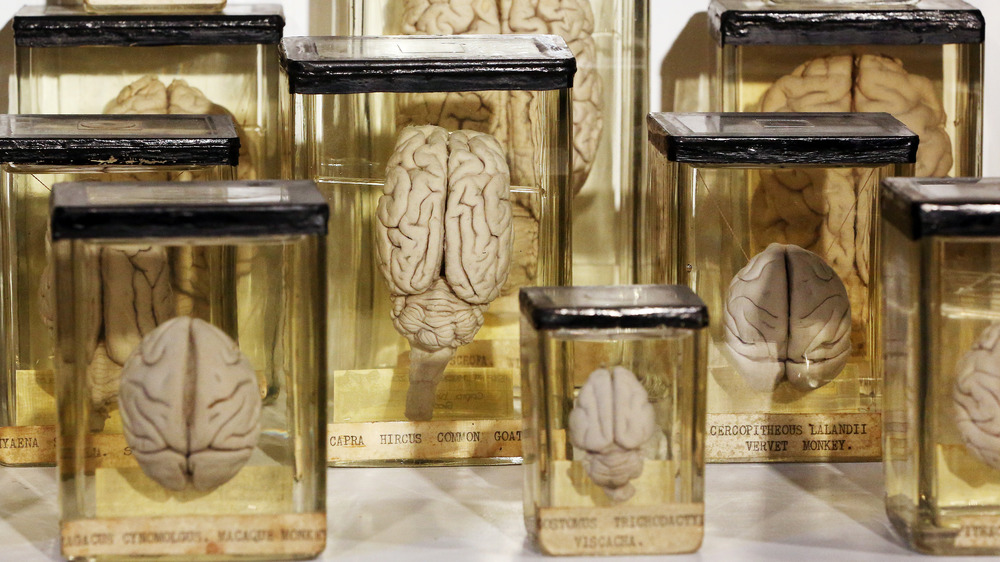

Although the reputations of the two men were irreparably damaged by the end of their lives, Edward Cope refused to be outdone, even in death. According to ThoughtCo, when Cope died in 1897, one of his last requests was to be autopsied and for his brain to be dissected in order to determine its size. Obviously, he wanted to make sure that it was bigger than O.C. Marsh's since thanks to eugenics it was believed that brain size correlated to intelligence.

But according to Science Focus, Marsh didn't take the bait. When he died in 1899, he decided to be buried in a cemetery near Yale's Peabody Museum.

Meanwhile, most of Cope's body was cremated and put in Philadelphia's Wistar Institute. His brain however, went to storage at the University of Pennsylvania. Writing in his will, Cope had hoped that "My brain shall be preserved in their collection of brains." However, as of 2020, Cope's brain reportedly remains unexamined, though it is still preserved somewhere in storage.