The Tragic Story That Inspired Island Of The Blue Dolphins

Many people were first introduced to the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island through a novel — Scott O'Dell's 1960 children's book, Island of the Blue Dolphins. According to The Guardian, it told the story of the preteen Karana, whose tribe living on a remote California island is decimated by duplicitous fur traders. When a large ship is sent to take them to the mainland, Karana leaps off the boat and goes to find her brother, Ramo. The two are left behind when a storm forces the ship to leave without them. Further events leave Karana alone on the island for many years, until the end of the novel brings another group of sailors who escort her to mainland California.

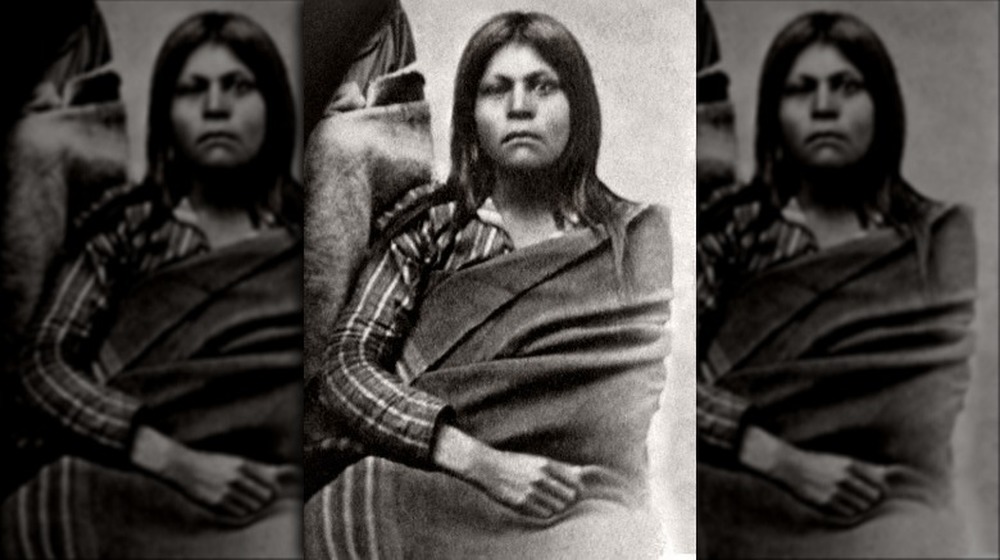

For all of its fictional elements, Island of the Blue Dolphins is taken from a real story. According to the National Park Service, the character of Karana is based on a woman who has been known variously as the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island, a "wild woman," and, after her conditional baptism by local priests in Santa Barbara, Calif., Juana Maria. The island where she spent 18 years in isolation is likewise real, though it's owned by the United States Navy and is closed to the public. Juana Maria's story is remarkable not only for the length of time she spent living alone on San Nicolas Island but for the years of history and legend that have built up around her tragic and deeply compelling tale.

A woman really lived alone on the Island of the Blue Dolphins for decades

San Nicolas Island is the most remote of the Channel Islands, an archipelago of eight landmasses off the coast of southern California. Five of them are now part of Channel Islands National Park. According to Atlas Obscura, San Nicolas is a separate piece of land under the control of the U.S. Navy that sits about 60 miles off the mainland.

The military presence and distance from the mainland aren't the most famous part of San Nicolas history, however. That honor goes to the person once called "The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island." This woman, whom the National Park Service reports was also known as Juana Maria and Karana, was stranded there for 18 years after a series of events decimated her people, known as the Nicoleños.

Scott O'Dell's young adult book, Island of the Blue Dolphins, helped bring her story to light but fictionalized large parts of the tale. O'Dell is the one who gave her the name "Karana," though no historic record indicates that she ever went by this name. Early additions to her story further muddy the waters, like the 19th century versions of the tale that claim she marooned herself to save a younger brother or her own son. Even her contemporaries found the idea of her deeply compelling, given that, for years, some sent ships to her island to search for the mysterious woman who had been left behind there.

No one knows the Lone Woman's real name

The woman who lived alone on San Nicolas Island for nearly two decades presents a deep and compelling mystery. Though records from this time give a relatively thorough overview of the events that led her to such a lonely stretch of time by herself on the island, relatively little is known about the woman herself, including her name.

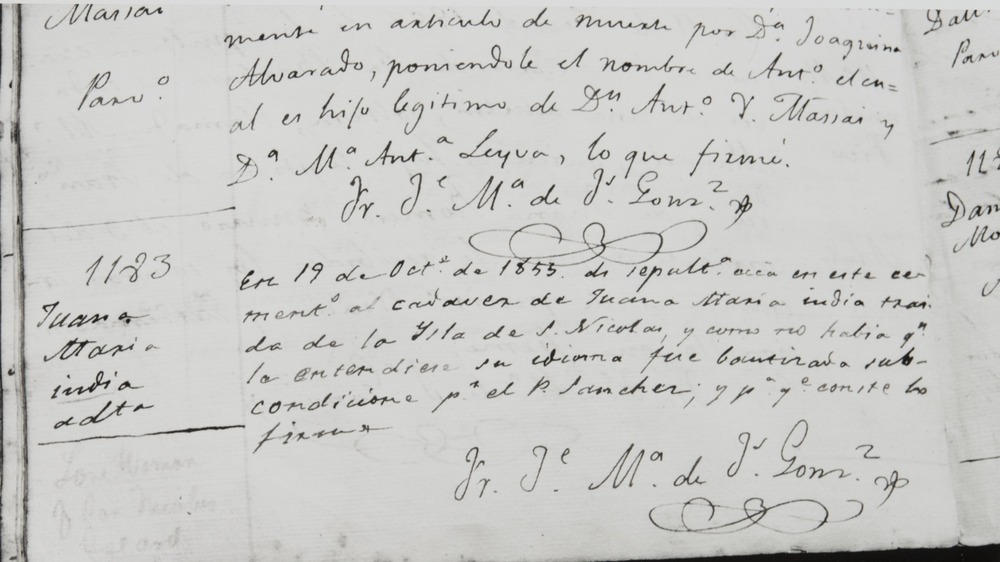

According to LitHub, she's been granted plenty of names and titles in the years following her arrival on the mainland. She was often referred to as "The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island," which certainly described her situation but is hardly humanizing. Shortly before her 1853 death at the Santa Barbara Mission in California, she was conditionally baptized and given the name Juana Maria by a Catholic priest. This name is perhaps the closest to realistically giving her a name and some degree of humanity separate from legend.

Some may also know her as "Karana," from writer Scott O'Dell 1960 children's novel. However, O'Dell gave her that name for his story. "Karana" does not appear in relation to the woman in any document from that time. Juana Maria may have tried to communicate her native Nicoleño name, but, as practically no one spoke her language when she made it to Santa Barbara, it seems as if any chance to know what she called herself is lost forever.

Juana Maria's tribe had already been through serious trauma

Juana Maria's people were already sadly familiar with injustice and deep misfortune. San Nicolas Island was home to the Nicoleños, who had been living on the island for thousands of years, according to the National Park Service. The steep cliffs of San Nicolas were home to seabirds like cormorants and gulls, which provided a food source and decorative feathers for Nicoleños along with the island's other resources, like seal, fish, and otter.

By the 18th century, Russian and native Aleut hunters from Alaska sailed south to hunt otter for their pelts. In 1814, these otter hunters descended upon the island and killed many people, apparently having decided that the Nicoleño people were in the way. According to the Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, the massacre decimated the island's native population, shrinking the number of Nicoleños from about 300 to mere dozens. The reason? The National Park Service says that some contemporary reports from this time claimed that one of the off-island hunters had been killed by a native person. The massacre was meant as retribution.

As JSTOR Daily recounts, one Russian sailor was arrested in the wake of the massacre, but it was too little, too late. Not only were many Nicoleños dead, but the local sea otter population was overhunted and practically useless to the fur traders. The remaining small group of native people were left to deal with the devastation.

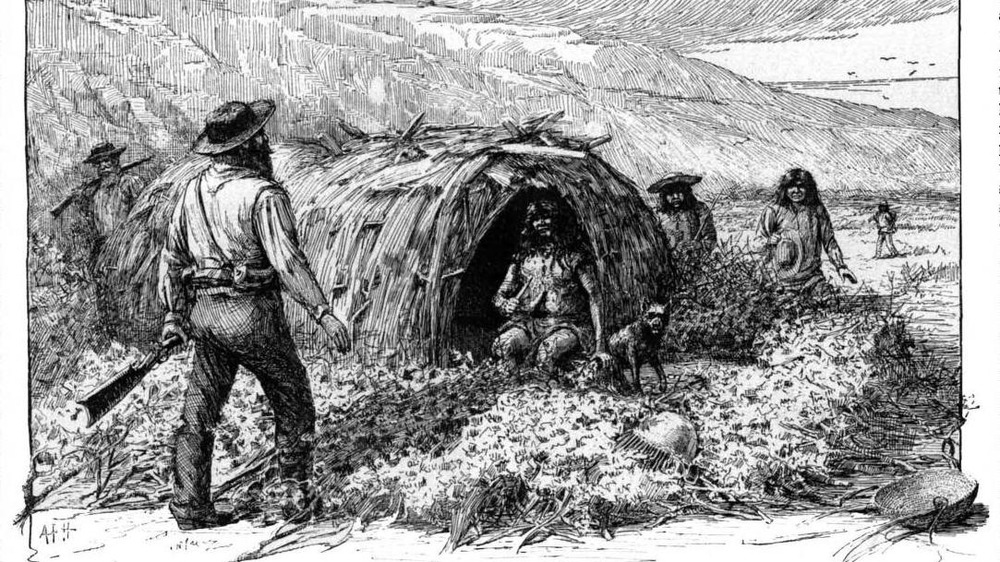

Priests removed people from the Island of the Blue Dolphins

In 1835, Catholic priests ordered the evacuation of the remaining Nicoleños. According to the National Park Service, religious members of the Santa Barbara Mission sent a Mexican ship, the Peor es Nada ("Better Than Nothing"), to the island. The Nicoleños had been hit hard not only by the 1814 massacre but by diseases brought by visitors to the island, to which the Nicoleños had practically no immunity. The remaining native people packed their things, boarded the ship, and were taken to the mainland. Many apparently ended up in Los Angeles, a relatively busy settlement that had a recorded 2,228 residents total.

The motivations of the priests are up for debate, says JSTOR Daily. Some sources have simply stated that they were concerned for the safety of the people of San Nicolas Island. However, it's also possible that the priests were eager not only to save the lives and souls of the Nicoleños for their own supposed good but for the priests' Catholic missions. A large group of newly converted and dependent Native American Christians would have provided a convenient labor force for the missions.

No one knows why Juana Maria missed the boat

While the rest of her tribe was being loaded onto ships to cross the channel to mainland California, Juana Maria was nowhere to be found. Or, according to other accounts, she was initially on the Peor es Nada but then dramatically leaped into the water and swam back to the island. Some say she was searching for her young child. Scott O'Dell's book imagines that she jumped ship to save a little brother.

A storm made the ship leave in a hurry, marooning Juana Maria on San Nicolas Island. According to the Los Angeles Times, sporadic attempts were made to rescue her over the years, but interest in her cause eventually faded. That didn't mean rescue attempts didn't occasionally happen. In 1850, 15 years after she was left behind, priests in the Santa Barbara Mission paid Thomas Jeffries $200 to look for her. The apparently lazy Jeffries merely circled San Nicolas and returned with only a shrug. Still, his attempt intrigued another sailor and adventurer, George Nidever. He made three trips to the island and found evidence of human habitation, from footprints to a tantalizing sighting of a woman alone on the island's shore. In 1853, on Nidever's final trip to the island, he and his crew would finally come face to face with the Lone Woman herself.

Juana Maria lived on San Nicolas Island for 18 years

One of the few certainties in Juana Maria's story is the amount of time she lived by herself on San Nicolas Island. From the 1835 departure of the other Nicoleños to her 1853 contact with sailors led by George Nidever, Juana Maria spent 18 years on her isolated patch of land.

According to JSTOR Daily, the men who made contact with her in 1853 reported that she was friendly and apparently healthy. There is no testimony from Juana Maria herself, so no one is sure how, exactly, she dealt with the extended isolation on San Nicolas Island. She was clearly a skilled hunter who would have lived off seals and birds she killed, along with fish and any forage available on the island.

The sailors reported that Juana Maria lived in a hut made out of large whalebones and brush. A report from Smithsonian Magazine also indicates that she may have lived in a nearby cave, where archaeologists uncovered evidence of human habitation there. However, the dig was interrupted by a claim from the Pechanga Band of Luiseno Indians, who alleged that they were effectively related to the Lone Woman. They argued that the dig disturbed potential human remains and funerary goods, which would violate a federal law known as the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). The U.S. government agreed to their request, and the dig has been paused indefinitely.

Juana Maria wasn't afraid to see new people

When Capt. George Nidever's ship landed at San Nicolas Island in 1853, Juana Maria greeted them with smiles and talk. She was, to all appearances, a healthy and friendly woman in her 50s. These initial descriptions contrasted dramatically with later, more embellished reports that depicted her as a "wild woman" who had completely abandoned any pretense of civilization, says JSTOR Daily. One individual quoted in a 1944 article in California Folklore Quarterly even said that she had lost all speech completely and was in a "semiwild condition." The real Juana Maria was in no such state. She was, in fact, clearly ready to communicate with Nidever and the other sailors, as she attempted to speak with them in her own language.

The group spent a few weeks on the island, where KCET reports that some sailors called her "Better-Than-Nothing," both for her company and in reference to the Peor es Nada, the ship that should have taken her off the island 18 years earlier. Juana Maria also showed the sailors how she survived all those years alone, demonstrating her hunting techniques and how she made fishing lines and hooks. Eventually, she boarded Nidever's ship and finally sailed to the mainland, where she quickly was transported to the Santa Barbara Mission and there reportedly put into the care of Nidever's wife.

No one could have a conversation with Juana Maria

During the few weeks Juana Maria and George Nidever's crew spent together on San Nicolas Island, it became clear that they had to deal with a significant language barrier. Even when Juana Maria arrived at Mission Santa Barbara on the mainland, no one could find any surviving Nicoleños who could have communicated to her directly. Linguistically speaking, Juana Maria was all alone.

Ernestine Ygnacio-De Soto, a Barbareño Chumash Elder interviewed by the National Park Service, says that her great-grandmother, Luisa Ygnacio, lived in the area at the time and had attempted to speak to Juana Maria. However, Juana Maria spoke Nicoleño, and Luisa spoke Barbareño Chumash. The two native languages were simply too different for the women to have a conversation.

The Santa Maria Times reports that other native people were able to talk to her, however, though only partially. The National Park Service reports that there are only four recorded words — "man," "sky," "hide," and "body" — in her language. It's clear that native language speakers weren't able to get much information from Juana Maria before her death, which was to come only seven weeks after her arrival. Even those few words are a little suspect, as confusion over what, exactly, Juana Maria was speaking about when she uttered those words isn't completely clear.

Juana Maria seemed to adjust to life off the Island of the Blue Dolphins

Though the hustle and bustle of a large, prosperous settlement like Santa Barbara was probably a shock after 18 years of isolation, Juana Maria seemed to take things in stride. According to George Nidever, quoted in Los Angeles: Biography of a City, she was delighted to see horses, which would have been large animals practically unknown to her. Juana Maria is said to have examined the animals closely when she had a chance, unafraid of getting close to learn more about the creatures. Nidever also reported that she reacted with clapping and dancing to see ox carts pulled around the area.

Juana Maria also reportedly brought her possessions with her across the channel. These included not only the dress made out of cormorant feathers but other clothing, needles made of bone, and baskets. Nidever claimed that she frequently walked from the mission into the town of Santa Barbara, usually returning with new objects that had apparently been given to her by admiring townspeople.

Juana Maria was possibly the last of her tribe

Back in 1835, it's possible that the rest of the Nicoleños hoped for decent lives when they were removed from San Nicolas Island. Maybe they hoped for an existence where they weren't massacred simply for being in the way. Perhaps some, at least, were curious about the world beyond the shores of their island. Yet, despite all of the historic records out there, very little is known about the fate of Juana Maria's fellow native people from San Nicolas Island.

When Juana Maria made it to Santa Barbara in 1853, she was one of the very last Nicoleños alive. According to the National Park Service, sacramental registers from 1835 and 1836 show that four likely Nicoleños were baptized at the Los Angeles Plaza Church. They would have been placed with Mexican "godparents" and also were subject to a number of forced relocations throughout the city over the next few years. Records for Nicoleños grow increasingly rare from this point. One, a boy who would have been about 5 years old when he left San Nicolas Island in 1835, appears to have been alive in 1853, when Juana Maria made it to Mission Santa Barbara. However, there are no records that any remaining Nicoleños were nearby when she arrived, much less able to speak with her.

The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island became a local curiosity

Often described as a "wild woman" by reporters, Juana Maria became something of a local attraction for the people in and around Santa Barbara. They flocked to the already bustling mission, hoping to get a glimpse at the near-mythical "Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island." According to California Missions, she also enjoyed receiving visitors like local priests.

Visitors who came to gawk at her sometimes saw her perform traditional songs and dances from San Nicolas Island, reportedly to the delight of young children. Yet, no one understood her beyond what could be established through gestures and the rare word shared between Juana Maria and other native language speakers. Still, something of her language might just survive.

According to the National Park Service, one native Chumash man named Melquiades claimed to have learned a "toki toki" song from Juana Maria. He taught it to Fernando Librado, a fellow Chumash, who then sang for a 1913 wax cylinder recording made by anthropologist John Peabody Harrington. Given the years and two people that separate the recording from Juana Maria herself, it's not certain that she really sang it. However, the mixed feelings of sadness and joy said to be expressed in the song are certainly in line with what Juana Maria herself must have felt as she adjusted to life at Mission Santa Barbara.

Juana Maria didn't live long after she left her island

After only seven weeks on the mainland, Juana Maria grew deathly ill, California Missions says. Records state that she was sick with dysentery, an intestinal infection that can be caused by a variety of bacteria or parasitic organisms. Historians can't be sure what, exactly, caused her final illness, though JSTOR Daily notes that native people in this region, like so many others, were often felled by epidemics that routinely decimated workers in the Santa Barbara mission and beyond. Native people like Juana Maria often did not have immunity to diseases that were familiar to groups of European colonizers.

As she still could not fully communicate with the people around her and give her consent, Father Francisco Sanchez conditionally baptized her into the Catholic church. As per the National Park Service, Sanchez gave the Lone Woman her Spanish name, Juana Maria, at a time when she would have been very near death and probably not conscious of its meaning. That name can still be found in the Santa Barbara Presidio burial registry, which also includes information about her death and burial on Oct. 19, 1853.