Before The Queen's Gambit There Was Vera Menchik

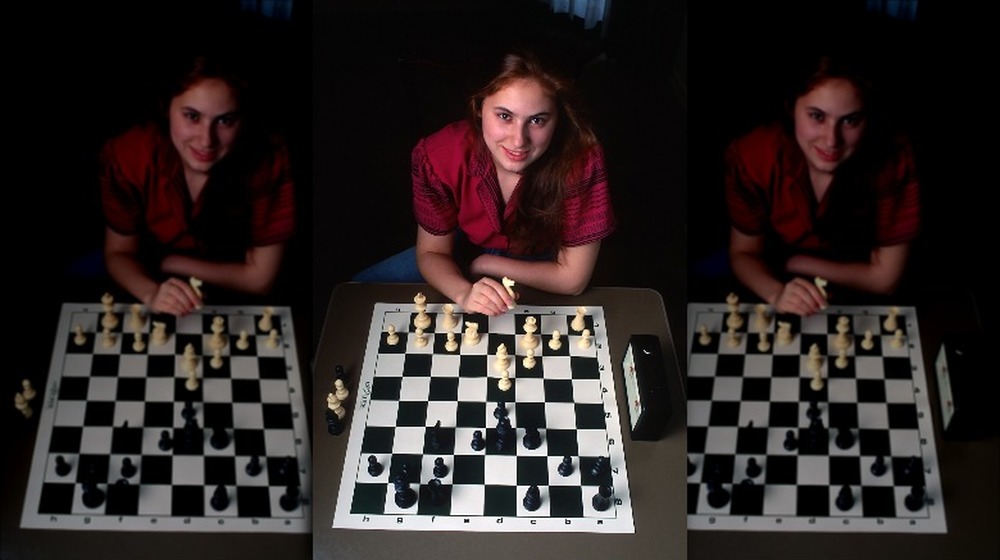

The Queen's Gambit has been a breakout success for Netflix, reintroducing the world to Walter Tevis' terrific novel and inspiring a surge of interest in the game of chess. The story of Beth Harmon — orphan, alcoholic, and chess genius — the series combines a fine sense of 1960s style with an accurate portrayal of just how dramatic the chess world can be. And while the story only skims the challenges faced by female players in the male-dominated sphere of world-class chess, it's easy to see Harmon as a feminist icon who smashes through glass ceilings as easily as she smashes through her endgames.

Which means a lot of people are disappointed to discover that Beth Harmon is an entirely fictional character (though you can play her over at Chess.com if you're into serial humiliation). Tevis based Harmon on his own experience playing chess and on several historical players, most notably Bobby Fischer. Which means Harmon is based on a bunch of dudes.

While the chess world is historically a pretty dude-heavy place, that doesn't mean there weren't gifted female chess players. In fact, if you're looking for a female role model for chess-loving girls, you're in luck, because before The Queen's Gambit there was Vera Menchik. Menchik was one of the strongest players in the world in the first half of the 20th century, and anyone thrilled by Harmon should know more about her.

Vera Menchik lived through the the Russian Revolution

It's hard to imagine a more eventful childhood than the one Vera Menchik experienced. She was born in Moscow in 1906. As noted by The Washington Post, this was when Russia was still an empire, and her family was relatively comfortable. Her family owned a prosperous mill and lived in a large apartment in the city, and Menchik and her sister both attended a private school.

Then, when Menchik was 11 years old in 1917, the October Revolution toppled Tsar Nicholas II. While many incorrectly believe that the transformation of Russia into a communist state was fast and efficient, the truth is Menchik would have experienced violence and near-constant disorder during these times. After all, the imperial family, the Romanovs, had ruled Russia for centuries, and the sudden collapse of not just the government but of every single element of the state transformed Russia into pure chaos. As detailed by National Geographic, Menchik and her family would have witnessed the rapid unraveling of society as different governments formed and fell, and different political and military factions squared off in a civil war that lasted more than five years.

As noted by historian Nicolas Werth, Menchik's home, Moscow, wasn't insulated from the chaos. There were hurried trials and mass executions, and often citizens had no idea who was actually in charge on a given day. It must have been quite a shock for a thoughtful young girl.

Vera Menchik's family lost everything

Revolutions are usually violent conflicts, and in any conflict there are winners and losers. When the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia, the country was transformed into a communist nation. Everything changed for Vera Menchik and her family quite suddenly. As noted by The Washington Post, like many wealthy and middle-class families in Russia, they were considered enemies of the state due to their "bourgeois" status. The family mill was nationalized and taken over by the government, and they were forced to share their comfortable Moscow home with several other families — and eventually had to move out altogether.

According to Femalista, Menchik suffered tremendously. She had to stop attending private school and had to resume her education at a school without heat, running water, or electricity. The students studied in their coats and hats by candle light and then had to walk home nearly an hour in the snow.

These conditions were intolerable, and the Menchiks eventually decided to leave their home. The Hastings Chess Club notes that at this moment, Menchik's parents split up. The specific reasons are unknown, but considering the stress the family was under it's not terribly surprising. Her parents divorced, and Menchik's father returned to his home in Bohemia while Menchik and her younger sister Olga accompanied their mother to England to start over.

Vera Menchik started playing chess because she didn't speak English

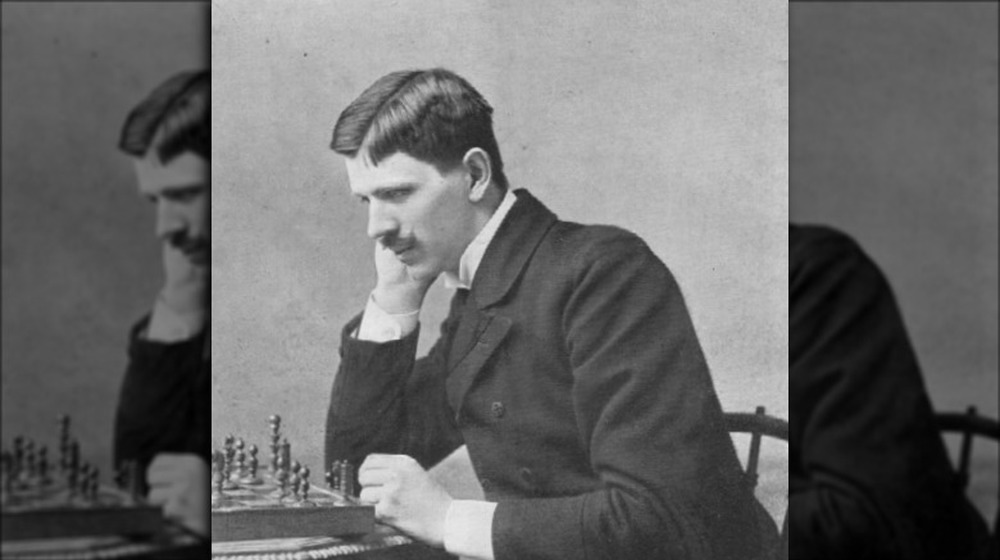

Vera Menchik was introduced to chess by her father. As reported by Salient Women, he gave her a chess set as a present when she was 9 years old and taught her the fundamentals of the game. Menchik took to the game immediately — a few years later she took second place at her school's chess tournament.

Although Menchik's mother was English, and she'd visited England as a young girl, Menchik only spoke Russian. After the Russian Revolution and the chaos of the civil war drove the family to flee, Menchik found herself in the town of Hastings, England, with her mother and sister. She didn't speak the language and found adjusting to her new home extremely difficult. According to The Washington Post, Menchik found the "quiet" aspect of chess alluring. She said, "chess is a quiet game and therefore the best hobby for a person who cannot speak the language properly."

According to Chess.com, Menchik screwed up the courage to join the Hastings Chess Club in 1923. Since she already knew the game well, she didn't need to speak English to study. She began taking private lessons from John Drewitt and eventually began studying with grandmaster Géza Maróczy. Encouraged by Maróczy, Menchik played in the Hastings Chess Championship in 1924 and managed a draw against the English women's chess champion, Edith Price.

Vera Menchik was the first World Women's Chess Champion

Just like Beth Harmon in The Queen's Gambit, Vera Menchik became a force to be reckoned with in chess at a very young age. Her main chess mentor was the grandmaster Géza Maróczy, whose style was focused on defensive and positional play. As noted by Salient Women, Menchik's own style favored positional brilliance and the sometimes incredible ability to pounce on any mistake her opponent made.

Under Maróczy's tutelage, Menchik soon found her footing and became a very strong player. After playing in a few local tournaments in Hastings, she was ready for a bigger platform, and in 1927 at the age of 21 she found it — The Women's World Chess Championship.

As noted by Chess.com, Menchik was already regarded as one of the strongest female players in the world by 1927 — and she proved it by winning the first-ever Women's Championship. Then she proved this wasn't any sort of fluke by holding that title for the next 17 years — until her death in London in 1944. Over the course of those years, Menchik faced several robust challenges to her status as the best female player in the world but triumphed over all of them. The only word sufficient to describe her career as women's champ is "dominance."

Vera Menchik was a trailblazer

Vera Menchik wasn't the first woman to play chess — or even the first woman to play chess at a very high level. But Menchik was a trailblazer for women in the game because she was one of the first to regularly beat her male opponents, even grandmaster-level players.

As noted by Chess.com, after winning the Women's World Championship in 1927 (a title she held until her death 17 years later), Menchik concentrated on breaking into mainstream chess tournaments — which meant male-dominated tournaments. She quickly established that she was more than capable, and in 1929 she was invited to play a tournament in Ramsgate and played brilliantly, tying with the legendary Akiba Rubinstein for second place and finishing just half a point behind Jose Raul Capablanca, who is regarded as one of the greatest chess players to ever live.

This success earned Menchik an invitation to participate in the fourth international master chess tournament in Karlsbad, Czechoslovakia, in 1929. She was the only woman to be invited, and while she only scored three points in 21 games, the reigning world champion, Alexander Alekhine, praised her performance and noted that with more experience she would be a "high-classed international champion." A famous photo of the event makes it clear how isolated Menchik was — the 21 men sit close together, relaxed, while Menchik sits tensely slightly apart, leaning away from her fellow players.

Vera Menchik experienced a lot of chauvinism and sexism

If your only knowledge of chess comes from The Queen's Gambit, you might be under the impression that while strong female players are rare, they were generally treated well. While Beth Harmon encounters some minor chauvinism in the beginning, it's little more than a few sarcastic comments and impolite gestures. She's quickly treated like the strong player she is.

The truth is, female players like Vera Menchik had to deal with much worse. As reported by The New York Times, the only woman to ever be ranked in the chess top 10, Judit Polgar, tells a very different story. She says that her male opponents insulted her, made jokes at her expense, and often refused to shake hands when she beat them — and this was in the 1990s and early 2000s, not the 1960s. When Susan Polgar, Judit's sister and also a talented chess player, qualified for the Men's World Chess Championship in 1986, she wasn't allowed to participate because of her gender.

That matches Menchik's experience. In fact, as reported by Chess History, when she participated as the first and only woman in the 1929 Karlsbad tournament, a player named Albert Becker scorned her as an opponent and suggested that the Vera Menchik Club be formed —membership limited to anyone she actually defeated. Becker soon became the first member of that club — and the club became a badge of honor, with the newest victim declared president — until someone else lost to Menchik.

Vera Menchik sacrificed her chess career to take care of her husband

In 1937, when Vera Menchik was 31, she married Rufus Henry Streatfield Stevenson. As noted by writer Robert B. Tanner, the two met through chess — Stevenson was a "chess personality of moderate strength in play" who had been married to Agnes Lawson Stevenson, a very strong female player active in chess tournaments. He and Menchik married a few years after Agnes' death, and by all accounts their brief marriage was a happy one.

The marriage was brief because, as reported by Insider, Stevenson was chronically ill when he and Menchik met, and his health continued to decline. Menchik made the difficult decision to withdraw from tournaments in 1937 in order to take care of her ailing husband. This continued through 1938, meaning Menchik lost a lot of competitive play time while she took care of Stevenson.

Menchik did play a little during this period. Her marriage to Stevenson had finally gained her British citizenship, so she could participate in the British Chess Championship and represent England in international competitions, which she did in Buenos Aires in 1939.

Stevenson suffered a massive heart attack in 1943 and died — and Menchik lost several more months as she recovered from the shock of that loss. What she might have accomplished if she'd played at full capacity during this period.

Vera Menchik would have been a grandmaster

When people talk about being a "master" or "grandmaster" chess player, they aren't being complimentary — these are official rankings. As explained by The Spruce, chess players are rated based on their performance against other players, and the title of grandmaster is awarded by the World Chess Federation (FIDE) to a player with an official FIDE rating of 2500 or higher. According to iChess.com, there are about 800 million ranked chess players in the world, and only about 1,500 of them are grandmasters.

Which means Vera Menchik would have been considered a grandmaster. As Chess Metrics notes, her rating in 1929 was 2535, when she was ranked as the 52nd best player in the world. That would have qualified her for the title — if it had existed. Unfortunately, FIDE didn't create the title of grandmaster until 1950, six years after Menchik's death. While the title is often informally granted to obviously dominant players retroactively, Menchik missed out on her chance for official recognition.

To put it all in perspective, the rating system goes up to 3000, although no one has gotten close to that as it would indicate absolute perfection. The all-time record chess rating is 2882, held by current World Champion Magnus Carlsen.

Vera Menchik was the first woman inducted into the Chess Hall of Fame

In modern times, every organization seeking prestige opens a Hall of Fame. It's a great way to celebrate your best and brightest, and it's a powerful publicity tool. Chess doesn't have the glamour of baseball or rock and roll, but it does have a Hall of Fame. Established in 1986, ChessBase reports the hall moved to St. Louis in 2011 and continues to be a major tourist attraction.

The Chess Hall of Fame maintains two lists of inductees, one just for the United States (including Benjamin Franklin!) and one for the world. The World Hall of Fame currently has just 37 inductees, including legends like Akiba Rubinstein, Richard Réti, Garry Kasparov (the former world champion who battled IBM's Deep Blue in the late 1990s) — and Vera Menchik.

In fact, as noted by the U.S. Chess Federation, as part of the hall's grand opening celebrations in 2011, Menchik became just the 16th person inducted into the Hall of Fame — and the first woman. In fact, she's one of just 13 women out of the 100 chess masters currently enrolled across both lists, demonstrating her importance to the game and to the history of women proving their intellectual equality to men.

There's a trophy named after Vera Menchik

Every two years the International Chess Federation (FIDE) holds Chess Olympiads, where national teams compete against each other for prizes. Broken into men's and women's events, the Olympiads attract the greatest current players, and the competition is fierce. Typically more than 150 countries participate, sending thousands of players to take part. The Olympiad events were organized haphazardly and informally starting in the 1920s but didn't become regular, official events until the 1950s.

As noted by author Bill Wall, when the Women's Olympiad was established in 1957, they chose to name the tournament trophy after one of the most important female players of all time, someone who would certainly have participated had she lived — Vera Menchik. For more than six decades, the winner of FIDE's Women's Chess Olympiad has taken home the Vera Menchik Cup.

Considering the fact that Menchik was born in Moscow and was forced to flee her home country after the October Revolution, Russia has dominated the Women's Chess Olympiad. According to The Encyclopedia of Team Chess, the Soviet Union (later, the Russian Federation) has won 11 gold medals at the event over the years, easily outpacing second-place China, which has six.

Vera Menchik wasn't obsessed with chess

In books and movies, genius is often depicted as a form of mental illness. In The Queen's Gambit, for example, Beth Harmon is depicted as being totally obsessed by the game to the detriment of almost every other aspect of her life. She ignores personal relationships, abuses drugs and alcohol, and spends almost all of her time reading about, thinking about, and playing chess. She even regularly hallucinates a chess board over her bed.

People like to think that this is part of the cost of genius, but the reality is often quite different. Vera Menchik, for example, was a dominant chess player. As reported by British Chess News, she was the first World Women's Chess Champion in 1927 and held that title until her death 17 years later. She was the first woman inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame. And yet, as noted by the Hastings Chess Club (where she got her start and her early training), she wasn't obsessed with chess at all. Menchik garnered a reputation as a calm and careful player, but she was never regarded as a tactical genius, and she didn't live and breathe the game like Beth Harmon. In fact, she had a lot of other interests, including tennis and sculpture (some of her art was even exhibited locally), and she was a warm personality with a lot of friends.

Vera Menchik died tragically

By 1944, Vera Menchik had lived quite the life. Born in imperial Russia, she'd experienced the Bolshevik Revolution firsthand, watched her family lose everything, moved to a foreign country where she didn't speak the language, and then established herself as the best female chess player in the world. She married in 1937 but lost her husband just a few years later.

Seemingly destined to live a life of excitement, The Washington Post reports that Menchik was living in London with her sister Olga and her mother when World War II broke out. As MilitaryHistoryNow reports, London had been savagely bombed by the Nazis in the early days of the war, a time referred to as The Blitz. Adolf Hitler thought he would be able to invade from France and wanted to terrify and weaken England as much as possible. But as the war ground on, the bombings ceased — until 1944, when Germany launched a second blitz called Operation Steinbock. The operation was designed to retaliate against the Allied bombing raids that had begun to make Germany suffer.

Sadly, one of these bombing raids in London claimed Vera Menchik's life. The chess champion had been participating in a tournament in London. On June 26, 1944, a German bomb hit her house, killing her and her family instantly — and destroying all of her chess trophies.