Did Ben Franklin's Famous Kite Experiment Actually Happen?

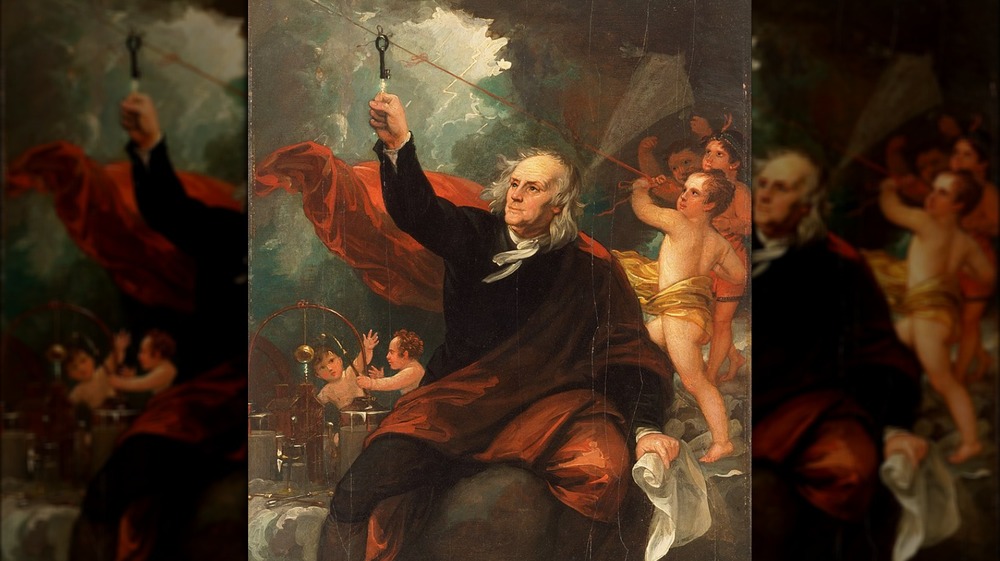

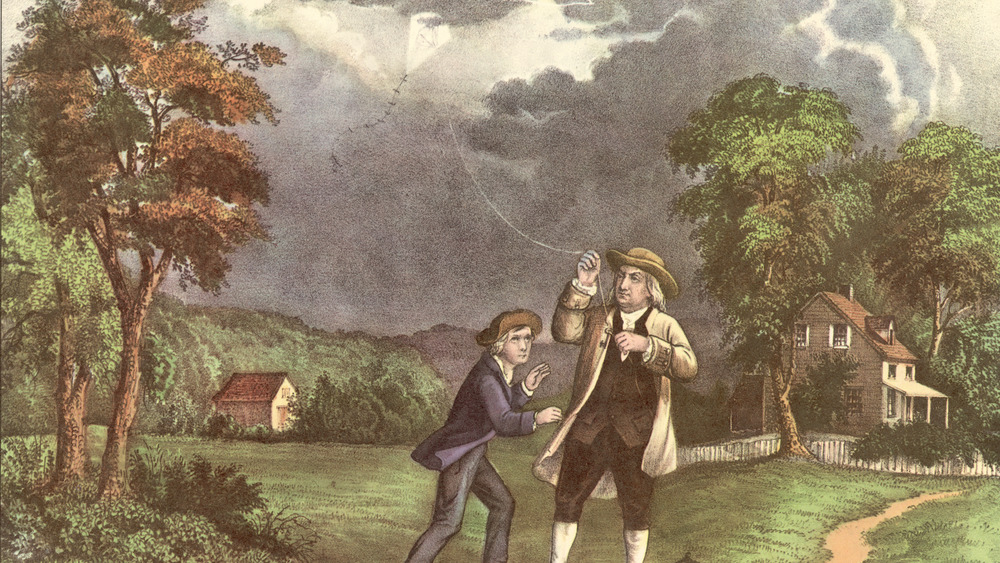

If you're an American, you no doubt learned about Benjamin Franklin's kite experiment at some point during your education. You know the basics already: Scientist-statesman Ben Franklin tied a key to the end of a kite string, took the kite out during a thunderstorm, and waited for lightning to strike. When it did, Franklin was able to prove that lightning is a form of electricity.

Franklin's experiment is a source of pride for many Americans, especially when so many of history's great experiments are attributed to Europeans. But did Franklin's kite experiment ever really happen? Or is it just another one of the myths we're raised to believe about our nation's Founding Fathers?

According to the National Archives, the first report of Franklin's kite experiment was published in the October 19, 1752 edition of The Pennsylvania Gazette, and was written by Franklin himself. In the article, Franklin encourages any curious individual to try repeating the experiment, and explains how they may do so. First, construct a kite with a metal wire on its top. Tie a metal key to the end of the kite's string, then add a silk ribbon to hold — and make sure not to get the silk wet (so you won't electrocute yourself) by standing "under some cover." When lighting strikes the kite, electricity will travel down the wet twine to the key, which will become noticeably electrified. Thus, we can conclude that lightning = electricity. Eureka!

Benjamin Franklin wrote about the kite experiment, but historians doubt the details

There's one thing that's particularly surprising about Franklin's 1752 account of the kite experiment in The Pennsylvania Gazette: Nowhere does Franklin ever claim that he performed the experiment. This has puzzled historians, some of whom have suggested that Franklin may have been reporting on an experiment performed by someone else, or simply describing a thought experiment of his. But, per the National Archives, a 1767 account of the kite experiment written by a friend of Franklin's, Joseph Priestley, confirms that Franklin did indeed conduct the experiment himself.

Even so, some historians doubt whether the kite experiment actually happened the way Franklin and Priestley described. In his 2003 book Bolt of Fate: Benjamin Franklin and His Electric Kite Hoax, historian Tom Tucker suggests that the experiment never occurred at all. Tucker points out that Franklin's description of the kite experiment was much less detailed than his typical writing style when describing his own research. Further, Tucker suggests that the kite experiment as described in the Gazette wouldn't actually work — but other historians, like Michael Schiffer, have disagreed with Tucker on this point.

Additionally, the MythBusters discovered that Ben Franklin would have instantly died after touching a key charged with the electricity from a direct lightning hit. But, per Mental Floss, many historians have interpreted the Gazette passage to suggest that Franklin's kite only collected ambient electrical charge from storm clouds, and was never directly hit by a lightning bolt.

Franklin's kite experiment wasn't the first to link lightning and electricity

Ultimately, historians are divided over whether or not Franklin's famous kite experiment ever did happen, but most agree that it could have happened. It's also worth pointing out, however, that Franklin's supposed kite flight was not the first experiment to conclusively prove the link between lightning and electricity.

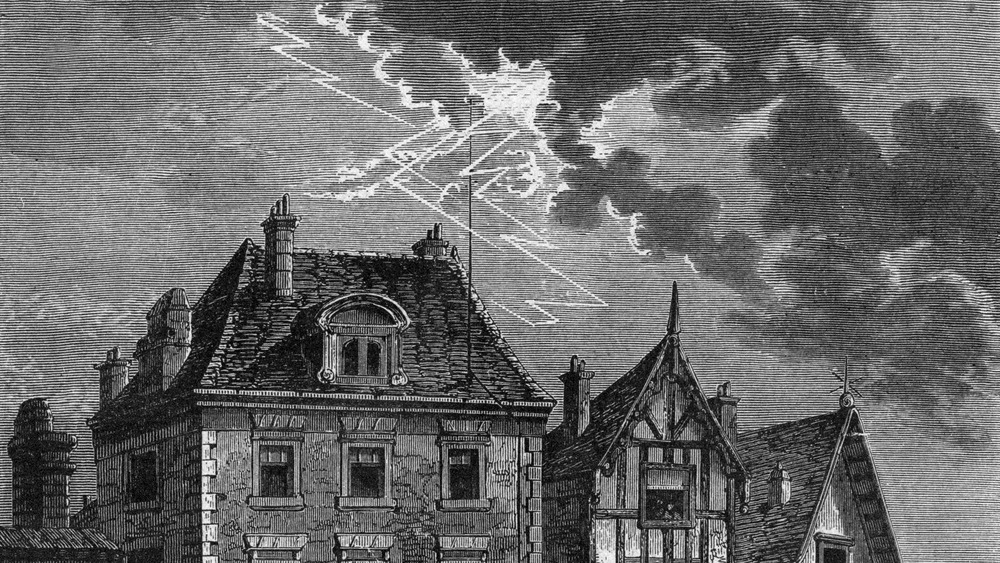

In 1750, per Mental Floss, Franklin sent a letter to his friend, fellow scientist Peter Collinson. In the letter, Franklin suggested that the link between lightning and electricity could be proven via experiment — not by a kite, but by a "lightning rod" on top of a tall building. Unfortunately, no building in Philadelphia was tall enough for the purpose at the time, so Franklin was unable to perform the experiment himself.

But a translated version of Franklin's letter began to cause quite a stir among the scientific community in France. In May of 1752, French naturalist Thomas-Francois Dalibard recreated the experiment Franklin laid out in his letter. Dalibard published the results, confirming the relationship between lightning and electricity, as well as the efficacy of lightning rods.

It wasn't until June 1752 that Franklin became fed up of the lack of tall buildings in Philadelphia and (supposedly) performed his kite experiment. While Franklin's experiment wasn't the first to confirm lightning's status as electricity, the actual first experiment was still inspired by his writing, so it's appropriate to give credit for the discovery to Franklin.