The Untold Story Of The Women Who Discovered The Universe

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, several women were hired at Harvard Observatory to look through photographic plates of stars and do the tedious work of classification. Working for half the pay that men received at the time, the work that these abled and disabled women did ended up being so important that they can be credited with discovering the universe (via Smithsonian).

Although some of these women were recognized and respected during their time, though mostly by foreign astronomical societies, today they have been widely forgotten. Most of them are known only by a misogynistic moniker named after Edward Pickering, the man who employed them, and even some of their work bears the names of men from their surroundings.

A quote in The Atlantic states, "Women have always been in the past, they just haven't been part of history," and the women who discovered the universe are no exception to this. And there were dozens of women, like Anna Winlock and R.G. Saunders, who worked at the Harvard Observatory and provided invaluable contributions to the field of astronomy. This is the untold story of just some of the women who discovered the universe.

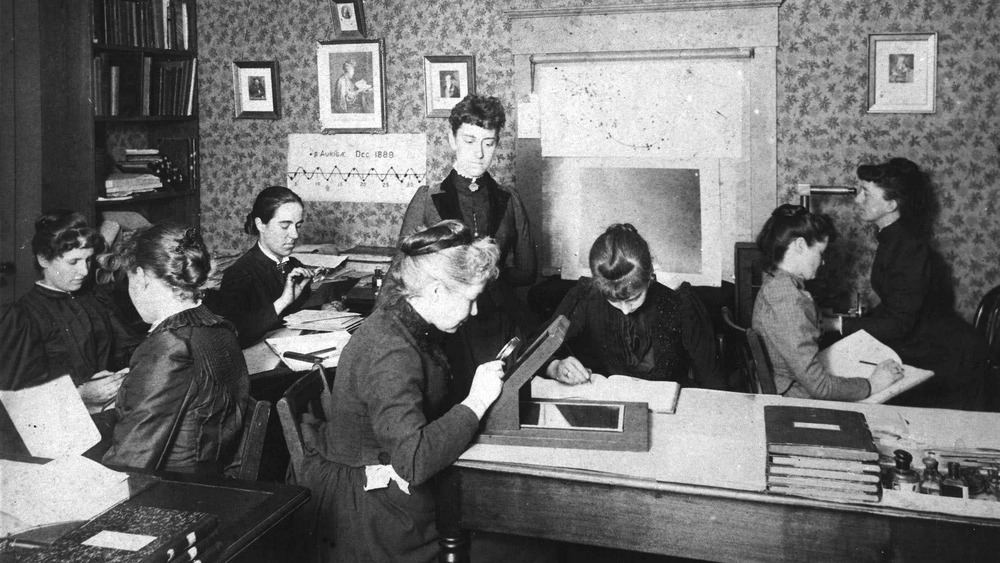

Women computers

When Edward Charles Pickering started collecting photographic plates of stars from all over the world, he realized that a team of people was needed in order to analyze the mountains of data. Pickering recruited a team of women who, working for 25 to 50 cents an hour for six days every week, became known as "Pickering's Harem" and the "Harvard Computers." According to "Pickering's Harem," by Barbara L. Welther, this moniker was so pervasive that it was used to describe women astronomers even after Pickering's death.

Since looking at photographic plates was considered to be unspecialized and tedious work, Pickering thought that women were perfectly suited for "large-scale work requiring little theoretical sophistication." According to The Women of the Moon, by Daniel R. Altschuler and Fernando J. Ballesteros, in a letter to astronomer George Ellery Hale in 1901, Frank Schlesinger, the director of the Yale Astronomical Observatory, noted that not only were women cheaper to employ, but "men are more likely to grow impatient after the novelty of the work has worn off and would be harder to retain for that reason."

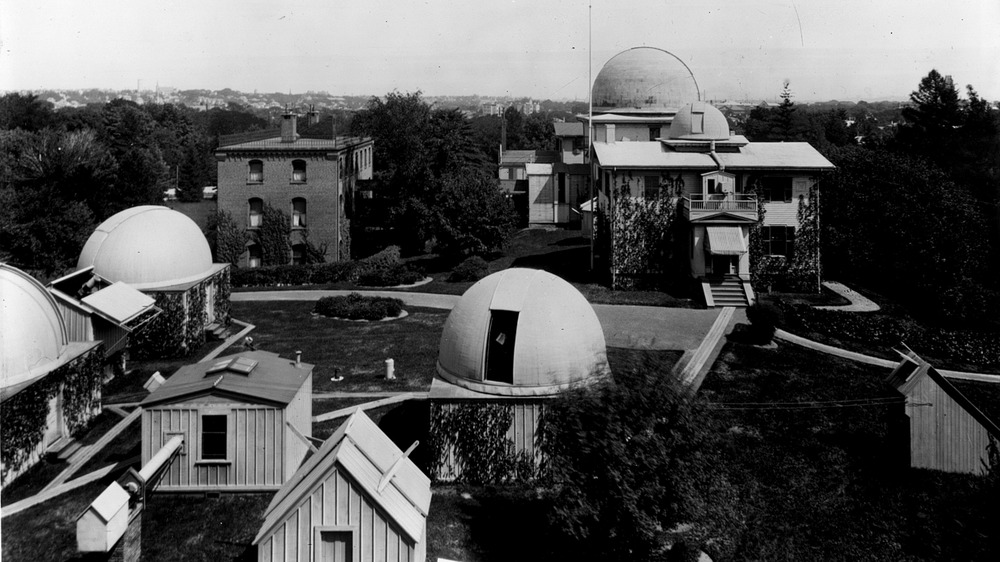

According to the Smithsonian Magazine, Pickering worked as the director of the Harvard Observatory from 1877 to his death in 1919, during which time over 80 women worked for him. And despite producing significant work in their own right, "the majority [of the women] are remembered not individually but collectively."

Women and science in the late 1800s

During the mid- to late-1800s, more women began attending colleges, especially once the "Seven Sisters" colleges opened their doors. But even though women were encouraged by their families to pursue science, and colleges began to invest in scientific research, men's colleges were far ahead in "access to equipment and funding for research," reports Smithsonian.

However, according to Gender Roles in American Life, edited by Constance L. Shehan, during this time many sought to dissuade women from education, claiming not only that women were genetically too inferior to do the work, but that education itself could be detrimental. In Sex in Education, published in 1873, Dr. Edward Clark wrote that "a woman's body could only handle a limited number of developmental tasks at one time ... girls who spent too much energy developing their minds during puberty would end up with undeveloped or diseased reproductive systems."

Even among the women recruited by Edward Pickering, few were allowed to make their own observations, and most were relegated to data analysis. According to When Computers Were Human, by David Alan Grier, Pickering himself was motivated by economics over equal opportunity, claiming that "To attain the greatest efficiency, a skillful observer should never be obliged to spend time on what could be done equally well by an assistant at a much lower salary." And true to his word, the rate that Pickering paid the women who worked for him was about half the rate that men typically received for the same work.

Who were the women?

When Edward Pickering became head of the Harvard Observatory in 1877, he noticed that the daughters, wives, and sisters of astronomers were already acting as assistants. Following suit, Pickering recruited some of these women while also hiring those with office experience and experience with mathematics.

Initially, the work involved computing the brightness and positions of individual stars. But once Pickering turned his focus onto photographic plates of stars, which were refined in 1878 when Charles Bennett figured out a way to "increase the sensitivity to light," the women he recruited got to work classifying and cataloguing stars.

Working in pairs, one of the women would examine the photographic plate and state her findings aloud while the other recorded the findings in a notebook. However, according to the Smithsonian Magazine, by limiting women to clerical work, Pickering "reinforced the era's common assumption that women were cut out for little more than secretarial tasks." They weren't allowed to use telescopes or to pursue their own investigations, and they certainly weren't considered equals. But while Pickering wasn't solely motivated by the desire to provide equal opportunity to women, he did believe that women were unjustly criticized when it came to their ability to participate in higher education, writes author Dava Sobel.

Anna Draper's donation

According to The Atlantic, None of Edward Pickering's research would have been possible without the donation of Mary Anna Draper, who essentially became Pickering's benefactress. The widow of Henry Draper, an amateur astronomer, Mary Anna Draper was both wealthy and well-connected, and as a result, she was able to have an incredibly large impact on the Harvard Observatory.

According to Physics World, Mary Anna had assisted her husband with astronomical observations during his life and after he died, she resolved to carry on his work. In 1884, she visited Pickering to give over some of her late husband's photographic plates and was impressed by the number of women she saw working for him. Two years later, she decided to personally fund Pickering's endeavor, and she created the Henry Draper Memorial Fund at the Harvard Observatory in honor of her husband.

Mary Anna Draper's funding ended up paying for dozens of women computers and was instrumental to the observatory's success. Her reach was so great that she even got Thomas Edison to donate equipment to Harvard.

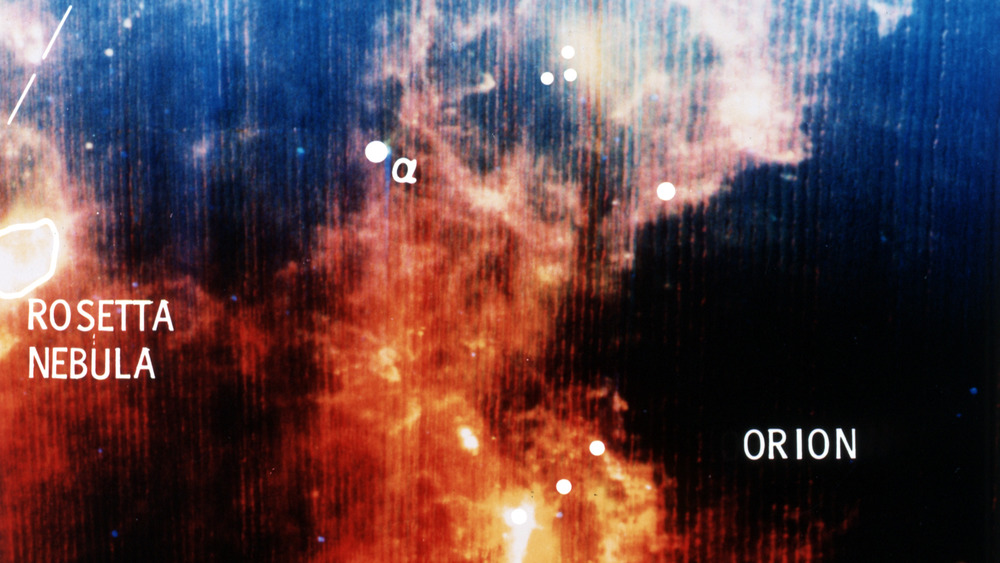

Williamina Fleming's nebulae

One of the first women hired by Edward Pickering was Williamina P. Fleming. Born in Dundee, Scotland, in 1857, Fleming originally worked as a teacher before moving to Boston with her husband and their child. But after her husband deserted them, Fleming got a job working for Pickering as his maid.

According to Women and Science, by Suzanne Le-May Sheffield, in 1881, Pickering became so frustrated with the men working for him that he declared "even his maid could do a better job of the copy and computing work than they were doing." Fleming ended up outshining all of Pickering's assistants, who were men, to the point where Pickering told Fleming to hire more assistants who were women.

According to Dangerous Women, over the course of nine years, Fleming catalogued over 10,000 stars and discovered over 50 nebulae. One of the nebulas that Fleming discovered is famously known as the Horsehead Nebula, although "all subsequent articles and books deny her credit" because J.L.E. Dreyer, the compiler of the first Index Catalogue, removed her name from the list of objects, "attributing them all instead merely to 'Pickering,'" as per Scientific Women.

However, Fleming didn't go unrecognized during her life. In 1906, she became the first American woman to be made an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society of London. And just before her death in 1911, she was awarded the Guadalupe Almendaro medal from the Astronomical Society of Mexico for her discovery of new stars.

Annie Cannon's classification system

Annie Jump Cannon was also hired as part of the "Harvard Computers" in 1896. Cannon had studied astronomy and physics at Wellesley College and due to a bout of scarlet fever during her studies, she was almost completely deaf. With a career lasting over 40 years, Cannon ended up becoming the first woman elected an officer of the American Astronomical Society, as well as the first woman awarded an honorary doctorate from Oxford University (via the Brooklyn Museum).

According to the University of Houston, Cannon was known for being incredibly speedy in her work, classifying over 225,000 stars in her life "at a rate of up to three hundred per hour." Cannon was also instrumental when it came to how stars are classified, improving upon the classification system developed by Williamina Fleming and Antonia Maury and creating a system used to this day.

While Fleming had created a classification system with 22 different classes, Maury had introduced a comparatively more theoretical or astrophysical version. Cannon created a third scheme, a simplified version of Maury's ordering, that put stars into spectral classes based on their Balmer lines, says Scientific Women, later understood to represent the star's temperature.

According to Cosmos, Using the mnemonic "Oh, Be A Fine Girl, Kiss Me," astronomy students memorized Cannon's spectral classes for decades. Although new spectral types have since been created to classify cool stars in the infrared spectrum, the classification created by Cannon remains the foundation of stellar classification. But despite Cannon's invaluable efforts, her system remains known as the Harvard spectral classification system.

The Henry Draper Catalogue

Annie Jump Cannon was also responsible for one of the largest collections of star classifications in the world. The first collection, known as the Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra, had been published in 1890 and was largely the work of Williamina Fleming. But after Cannon created her new spectral classification system, she and her coworkers started putting together the Henry Draper Catalogue.

According to the San Diego Supercomputer Center, the nine volumes of Cannon's Draper Catalogue classified over 200,000 stars in the end, and Cannon's work was "valued as the work of a single observer." But unfortunately, Cannon received little-to-no recognition for this achievement either, as the catalogue was named after Draper's late husband, as were the extension catalogues.

Although Cannon's achievements went relatively unnoticed, the lack of awareness towards her achievements was noted in The Woman Citizen. According to the Smithsonian Magazine, in the June 1924 issue, The Woman's Citizen lamented that "The traffic policeman on Harvard Square does not recognize her name. The brass and parades are missing. She steps into no polished limousine at the end of the day's session to be driven by a liveried chauffeur to a marble mansion."

Extensions to the catalogue have since been published, bringing the number of stars classified over 350,000.

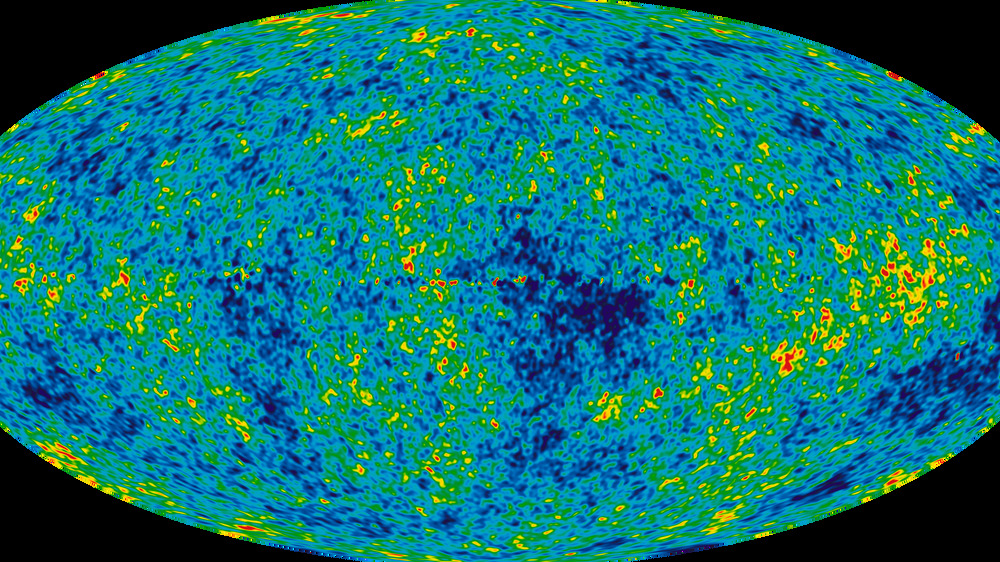

Henrietta Leavitt's discovery

The contributions of Henrietta Swan Leavitt were so invaluable that even Edwin Hubble acknowledged that she should have been awarded the Nobel Prize. Graduating from Oberlin College and the Society for Collegiate Instruction of Women, later known as Radcliffe College, Leavitt discovered astronomy in her final year (via PBS). Although an illness, likely scarlet fever, led her to spend several years at home after graduation and resulted in a partial loss of hearing, by 1895 Leavitt was volunteering at the Harvard Observatory.

Hired as a permanent staff within several years, one of Leavitt's methods involved placing the photographic plates atop one another in order to compare the changing brightness of stars depending on their exposure. In doing so, she discovered 2,400 variable stars, as per Space.com.

According to One Minute Astronomer, in 1912, Leavitt discovered that certain types of bright stars known as Cepheid variables "pulsated with a period directly proportional to its true brightness." Using the pulsation period of these stars, Leavitt was able to determine not only the true brightness of these stars but their true distance. This discovery of distance markers was revolutionary. Using Leavitt's discovery, Hubble figured out that the "Andromeda Nebula" was actually another galaxy over 2 million light years away. According to the University of Houston, Leavitt's technique became known as the "yardstick to the universe."

Paid $10.50 a week for her work, Leavitt died in obscurity at the age of 53. But without her, who knows when the universe would have been discovered.

Too little too late

Although Henrietta Swan Leavitt died in 1921, her work remains pivotal towards the investigation of the universe. Using Leavitt's pulsation theory of the Cepheid variables, Edwin Hubble was able to figure out the size and age of the universe, along with the fact that it was expanding. In the 1990s, scientists expanded this understanding by determining that this expansion was accelerating (via The Harvard Gazette).

And even though Hubble admitted that Leavitt deserved a Nobel Prize, he did nothing to ensure that she actually received it. By the time someone recognized her significance and made the attempt, it was too late. According to History of Scientific Women, in 1926, Swedish mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler tried to nominate Leavitt for the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Harlow Shapley, the director of the observatory at the time, wrote back to Mittag-Leffler letting him know that Leavitt had unfortunately died almost four years earlier. Shapley also suggested that the "true credit belongs to his (Shapley's) interpretation of her findings." Since the Nobel Prize isn't awarded posthumously, Leavitt never got her nomination.

And although Shapley had appointed Leavitt as the Head of Stellar Photometry in 1921, she unfortunately died from cancer later that very year. Despite everything, Leavitt was said to possess "the best mind at the Observatory" and has been called "the most brilliant woman at Harvard" (via PBS).

Everyone wants a woman computer

Because of the success of these women, many other observatories opened positions to women. According to The Madame Curie Complex, by Julie Des Jardins, Yale Observatory, the Yerkes Observatory in Washington D.C., and the Dudley Observatory in Albany, among others, were allowing women to work for them, most likely due to the success of Edward Pickering's women assistants.

And recognizing the strong presence that women had at the observatory, when Harlow Shapley, Pickering's successor, launched a graduate education program, women were offered some of the first spots. The special grants in aid that these women were able to receive "became the first stipends for graduate students," reports The Atlantic. One of the women who benefited from this graduate program was Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, whose doctoral thesis "established that hydrogen was the major constituent element of the stars."

In 1921, the American Men of Science magazine listed 20 women astronomers, and almost half of them worked as computers. This number only increased over the years. According to Women and Underrepresented Minorities in Computing, by William Aspray, in comparing the 1921 version with the 1938 publication, even the total number of female scientists "more than quadrupled."

According to Smithsonian Magazine, after racial discrimination in federal hiring practices was prohibited in the 1940s, Black women like Melba Roy, Katherine Johnson, and Miriam Mann went on to work as "human computers" for NASA, simultaneously fighting battles for equal rights while calculating rocket trajectories for the Apollo missions.

Pushing women out of computers

After helping build the tech industry and the foundations of modern astronomy, women were suddenly pushed out. According to Gender Codes, edited by Thomas J. Misa, in the mid-1980s, women stopped entering the field of computing while the proportion of women studying computing simultaneously began falling. While the proportion of women studying computing has continued to fall, this decline is considered unprecedented. "No other professional field has ever experienced such a decline in the proportion of women in its ranks."

According to The Washington Post, psychologists William Cannon and Dallis Perry were contacted by Systems Development Corp (SDC) to make an "aptitude assessment for optimal programmers" in the 1960s. After interviewing over 1,300 programmers, out of whom 186 were women, Perry and Cannon developed a profile to predict the "best potential programmer." Since the test group was dominated by men, the final assessment disproportionately identified men to be better candidates for programming. And since the hiring process would then favor men as a result, men became overrepresented in the field, creating a feedback loop that claims technology as a "masculine domain." Once the true potential of computers was discovered, "women were systematically phased out and replaced by men who were paid more and had better job titles," as per the Guardian.

Blatant sexism and harassment within also continue to make the tech industry a hostile workplace for women. According to The New Yorker, as of 2017, almost half the women who get tech jobs end up leaving the field.