History's Most Respected Geniuses That Turned Into Madmen

It was Aristoteles who said (via Psychiatric Times), "There is no genius without having a touch of madness." It's a sentiment that's been repeated so often it's become a cliché, and the mad genius — particularly the mad scientist — has become such a fictional trope. But there's a good reason it's so common: it's rooted in history and actual psychology.

Scientists have been trying to figure out just what the connection is between genius and mental illness, and according to LiveScience, the general consensus is that yes, there's something there. For instance, researchers speaking at the World Science Festival in 2012 shared results of an experiment that found people with bipolar disorder did better when they were given a word and asked to come up with associated words — while, at least, they were in a manic episode. They surmised that the sheer number of ideas generated by a manic mind made it more likely one would be a winner.

Obviously, that's just a small piece of a complicated set of issues, but it illustrates why it's believed there is something to madness and genius. Now, let's talk about some of the greatest minds in history... who descended into madness.

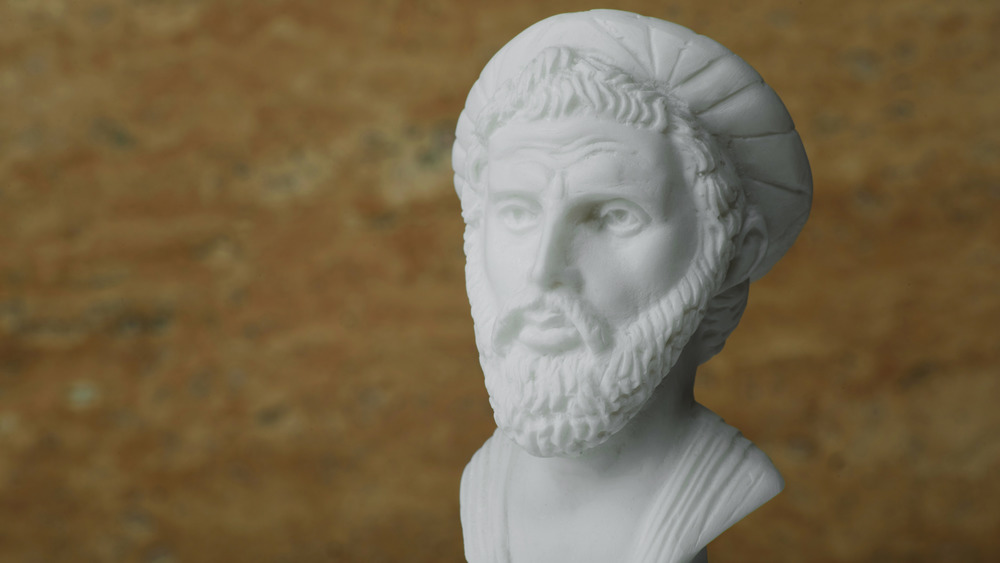

Pythagoras: hold the beans

Pythagoras is one of those near-mythical ancient Greeks who has managed to become the bane of math-hating students everywhere. He's most famous for his work with triangles, but according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, he was known among his contemporaries for his philosophical musings on the fate of the soul.

Separating the real Pythagoras from the idealized one is tricky, but let's give it a shot. Atlas Obscura says it's generally accepted that Pythagoras had a group of followers who lived communally and were entirely vegetarian... but avoided was fava beans, because of the belief they quite literally represented death. It was actually a long-held belief shared by the ancient Egyptians, but given the amount that Pythagoras' contemporaries ridiculed his hatred of beans, it seems he went above and beyond in bean avoidance. He didn't just think they were a symbol of death; he came to believe that each bean literally contained the soul of a dead person. While other ancient Greeks happily nommed away on beans, Pythagoras preached that bean plants were ladders to hell.

Pythagoras continued to take it very seriously, and according to the widely accepted story of his death, he was presented with two choices: flee across a field of beans, or die at the hand of a mob of people chasing him. He died.

Hedy Lamarr: chasing eternal youth

Hedy Lamarr was a beautiful genius: she was an actress, pin-up girl, and the inspiration for Disney's Snow White, but she was also the inventor of technologies that revolutionized military communications and guidance systems, changed the way planes were designed, and made today's WiFi possible. Part of the tragedy of her life was that she was neither recognized or compensated for her brilliance, and as her Hollywood career ground to a halt, she spiraled into a desperate search to remain relevant. Sky History says that after she failed at relaunching her career in the late 50s, things took a turn for the worse.

By the 1960s, she had gone from movie headlines to tabloid headlines, especially after her sixth divorce and shoplifting arrests. Fast forward to the 1970s, and Lamarr had become fully obsessed with finding the Fountain of Youth. She fell in with Max Jacobsen — also known as Dr. Feelgood — and was on a near-constant regimen of his so-called "miracle shots." They actually weren't miracles, they were — mostly — a mix of animal hormones and amphetamines. No longer wanted as a leading lady thanks to Hollywood's "ageist attitudes," she started one plastic surgery procedure after another in an attempt to recapture her youth. (She even pioneered some of the processes and developed techniques that would become standard.)

Eventually, she retreated to complete seclusion, interacting with people — including her own children — though telephone calls until her death in 2000.

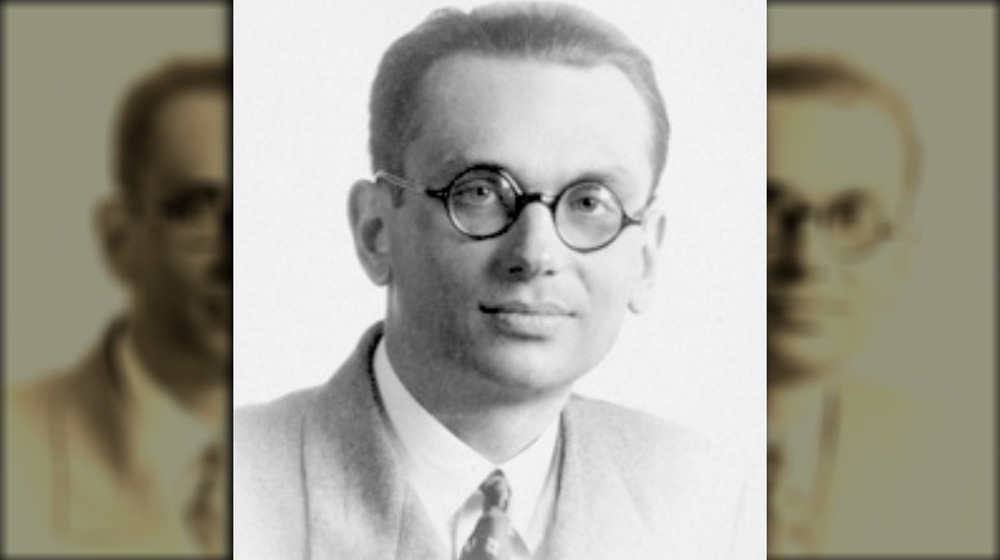

Kurt Godel: when hypochondria gets out of control

Time magazine counted mathematician Kurt Gödel among their "100 most influential thinkers" of the 20th century, and according to the Institute for Advanced Study, his work in math, logic, and philosophy was nothing short of groundbreaking. He's most well-known for his "Incompleteness Theorems," which basically says that within every theory there will always be something that cannot be explained.

Jørgen Veisdal, a research fellow at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, says (via Medium) that Gödel had suffered from hypochondria since childhood. It was so severe that he kept years' worth of records of everything from his temperature to the outcome of his bathroom breaks. He would obsessively devour things like over-the-counter medications and, in particular, heart medication: he was certain that his heart had been damaged by the rheumatic fever he suffered in childhood.

The paranoia deepened as Gödel got older, and he also came to suffer from iophobia — a fear he was going to be poisoned. In his later years, he would only eat that which his wife prepared for him, and when she was hospitalized and incapable of caring for him, he simply stopped eating. That was in 1977, and he died in 1978. He weighed just 65 pounds at the time of his death, and the official cause was "malnutrition and inanition caused by personality disturbance."

Howard Hughes: playboy, genius, germaphobe

Howard Hughes' life story is something out of a movie. In short, the millionaire playboy hit it big in Hollywood, then bought the airline TWA, built the largest seaplane in the world, and went from director to military contractor that revolutionized the industry and built the first American spacecraft capable of landing on the moon. According to the BBC, the same obsessive-compulsive disorder that caused him to wash his hands so much they bled was likely what helped him chase the perfection that made him so successful.

Hughes' OCD and germaphobia was encouraged at a young age by a disease-obsessed mother who checked him daily for signs of illness. According to the American Psychological Association, his lifelong symptoms spiraled out of control in the last two decades of his life. Obsessive handwashing turned into burning his clothing if someone around him was sick, or if he thought he'd been exposed to germs.

Contamination, he thought, came from the outside — which is what led to his reclusive retreat into hotel rooms that he viewed as germ-free. Tissue boxes protected his feet even as he wrote manuals on the proper way to open cans and serve food from them. At the same time, he neglected things like bathing and brushing his teeth, convinced that germs didn't come from him, but rather, they were after him. He died alone in 1976.

Nikola Tesla: pigeons and pearls

Serbian physicist Nikola Tesla is science's ultimate underdog, a brilliant mind overshadowed by the massive personality that was Thomas Edison. He's had something of a resurgence in popularity of late, lauded for not only his inventions, but his ability to design from start to finish entirely in his head.

According to the Smithsonian, it was into his head that he ultimately retreated. After years of suffering from disappointments and betrayals, Tesla truly started to withdraw from the world in 1912. By then, symptoms of his oddities were fully developed: he had an obsession with the number three, counted every step he took, was incredibly sensitive to sounds, and wrote freely of his "violent aversion against the earrings of women." (In particular, pearls.)

While he was living in a New York City hotel room (paid for by George Westinghouse), he became obsessed with pigeons in general and one pigeon in particular, a white female pigeon he was so fond of that he spoke of their love in very human terms. He later claimed that she visited him to tell him that his death was fast approaching, then died in his arms. It's suspected that today, he would be diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and that he would fall on the autism spectrum.

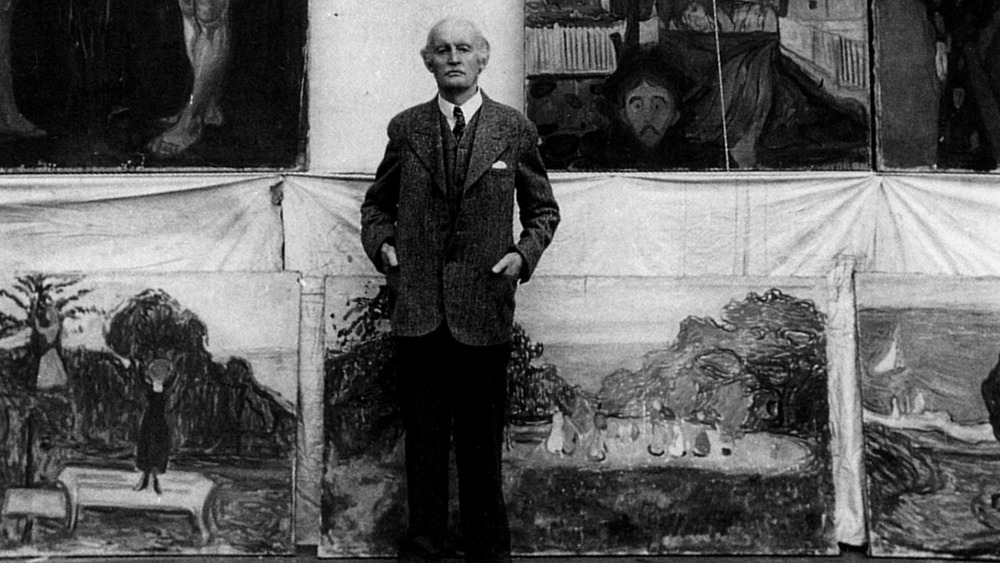

Edvard Munch: the scream

Edvard Munch is the genius behind one of the world's most iconic works of art: The Scream. Take a gander at the rest of his portfolio for some equally disturbing images, and two things quickly become clear: he wasn't just one of the most influential modern artists of his era, but there was clearly something going on with him. According to the Smithsonian, The Scream was the product of a hallucination he had while he was young, which he recalled happened alongside "a huge endless scream coursing through nature."

The troubles that haunted the man who heard that voiceless scream were long, and it started with the death of a beloved sister from tuberculosis, a disease he also contracted and survived. With another sister institutionalized, he once wrote that he had "the heritage of consumption and insanity." His life was dotted with trauma, including a relentless love affair he took part in against his will, and a confrontation that ended in a gunshot and the loss of one of his fingers.

Munch became more troubled as he grew older. His fits of rage and hallucinations became more frequent, and for his last 27 years, he lived alone in his home near Oslo. His only companions were paintings that he referred to as his children — and he couldn't bear to be away from them. After his death, authorities found he had locked himself in his home with nearly 20,000 works of art.

Buckminster Fuller: philosopher of the future

The Buckminster Fuller Institute describes its namesake as a "practical philosopher," and while his name might not be widely recognized, his most famous creation certainly is: the geodesic dome.

Fuller, says Wired, was afflicted with hypergraphia. That's the urge to write, and he absolutely did. In addition to being an architect, engineer, and cosmologist, he also managed to find time to record the daily events of his life... in 15 minute intervals, starting in 1917 and ending only when he died in 1983 (via Atlas Obscura). The result was the Dymaxion Chronofile, an archive that contains 140,000 papers along with audio and video recordings that would take around 1,700 hours to listen to. It's considered the most complete record of a person's life.

Open Culture says that Fuller adopted "dymaxion" — a combination of the words "dynamic," "maximum," and "ion" — to describe him as a brand, and it also described his weird sleep patterns. He came to believe that a person's energy was kind of like a reservoir, and decided it was more efficient to top up his sleep supplies every so often, instead of running empty and needing a long recharge. So, he switched to "Dymaxion sleep," which was basically a 30-minute nap every six hours. He did it for two full years, until no one else would adapt to his weird schedule and he felt forced to call it quits.

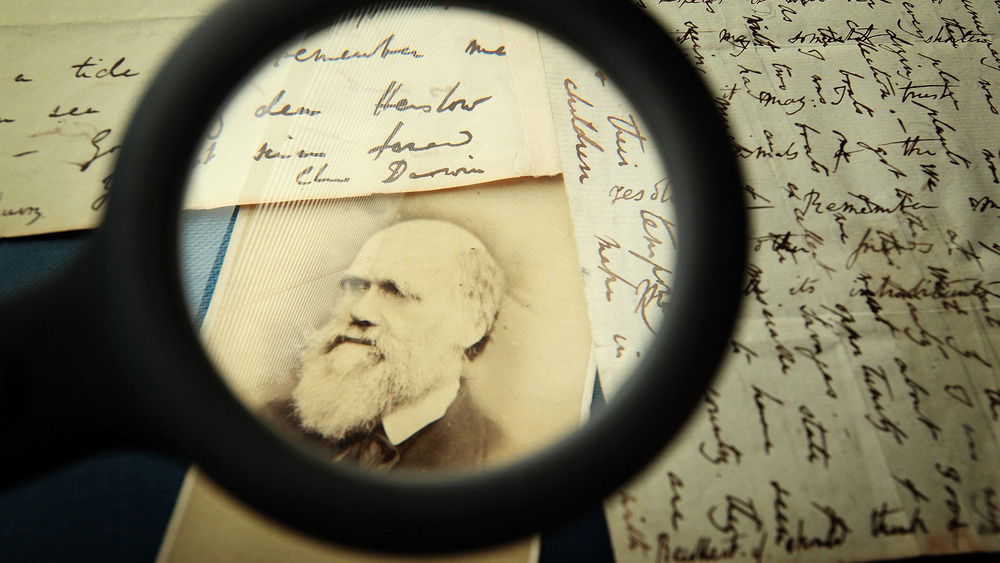

Charles Darwin: from globetrotting traveler to homebody

It was Charles Darwin, of course, who brought evolution front and center with his On the Origin of Species, and students are taught that he collected his evidence and observations while taking part in a 5-year journey aboard a ship called the Beagle. That's certainly true... but it's not the whole story.

Darwin was only in his early 20s when he was off gallivanting around on the Beagle, and once he returned to Kent, something happened. When he was 28, Science says he started suffering from severe panic attacks, fits of hysteria, and episodes of crying, vomiting, and nausea. He wrote about some dire stuff, including a recurring feeling of ominous doom, and feelings of something called depersonalization, which the Mayo Clinic describes as the feeling you're watching yourself from outside of your body, and that nothing is actually real. It got so bad, in fact, that Darwin dreaded leaving the house, and was overcome with panic at the thought of meeting with colleagues.

And that's the diagnosis that most scholars go with now: panic disorder. According to the LA Times, Darwin had written about suffering from nine of the 13 symptoms associated with panic disorder, and it's been suggested that had he not struggled with it, he may not have had the time or focus to write his seminal work.

Vincent Van Gogh: an eye — and an ear — for art

When it comes to the mad genius, perhaps no one embodies that more wholeheartedly than Vincent Van Gogh. It's common mythology that at one point he sliced off a piece of his earlobe and gave it to a prostitute, but according to The Guardian, that's not exactly true. In 2016, they reported that the Van Gogh Museum had discovered a letter from his doctor — Dr. Felix Rey — in which he described what had happened and what was (or, more accurately, wasn't) beneath those bandages. Van Gogh, Rey wrote, hadn't sliced off a bit of his ear lobe: he'd cut off his entire ear with a razor.

That kind of self-harm, they say, proved that there was something very dark indeed going on within Van Gogh, but historians aren't entirely sure what. They know that Van Gogh became an artist after a string of failed careers and in his lifetime, he was a failed artist, too — most of his works didn't sell. Guesses at a diagnosis are varied, and include things like schizophrenia and the side effects of syphilis. Depression seems a certainty, mania likely, and bipolar? Perhaps.

Van Gogh was committed to an asylum after he cut off his ear (with help from a petition signed by his neighbors) and continued to paint. He was 37 when he died, 30 hours after shooting himself point blank in the chest with a revolver.

Jack Parsons: believer in magic, summoner of demons

"Rocket scientist" is sort of code for "really smart person," and Jack Parsons was a literal rocket scientist — he was one of the founders of Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Wired says that Parsons could be considered the "father of rocketry," and probably would have been... if he hadn't been written out of JPL's and NASA's history for a long time.

Why? He was a weird guy. According to io9, it wasn't long after he invented solid rocket fuel and made a ton of money selling it to the US military that he started dabbling in other things, like sex magic with the goal of summoning a goddess named Babalon. Parsons came to believe that Babalon was eventually going to become the mother of the Antichrist, and in order to complete the rituals he recruited both his longtime girlfriend, and L. Ron Hubbard. When a red-headed artist named Marjorie Cameron showed up at their mansion, they became convinced that it had worked, and she was happy to play along.

Things went predictably sideways, and rumors of Communist sympathies resulted in the loss of Parsons' top secret security clearances. He held down a few random jobs before deciding he wanted to get into Hollywood and even deeper into the occult, but it wasn't going to happen: he was killed on his front porch while handling an order of explosives.

John C. Lilly: coincidence?

When it comes to fields of study, Dr. John C. Lilly's work was always a little out there. According to the LA Times, he was a neurophysicist most widely known for inventing the isolation tank and using it to try to isolate — and study — human consciousness. (The Guardian adds that he also studied dolphin communication and once played matchmaker between a woman and a dolphin... but that's a whole different story.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a scientist studying consciousness during the 1960s, he added LSD to his research tools. (He's pictured with Timothy Leary.) That was followed by a near-death experience where he nearly drowned in a hot tub, but became convinced that there was a higher power that had saved him.

That power was coincidence, he believed — it was a coincidence that his friend had showed up just in time to save him, and that led him to develop the idea of the Earth Coincidence Control Office (ECCO), which he believed had recruited him as a spy. He later wrote a whole series of directives by which the Cosmic Control Center (CCC) determined what coincidences were going to happen when. He also went on to describe Alternity, a place where all possibilities are laid before a person's consciousness, and describe himself as "outsane" — which is the sort of sanity that allows a person to peek outside their external reality.

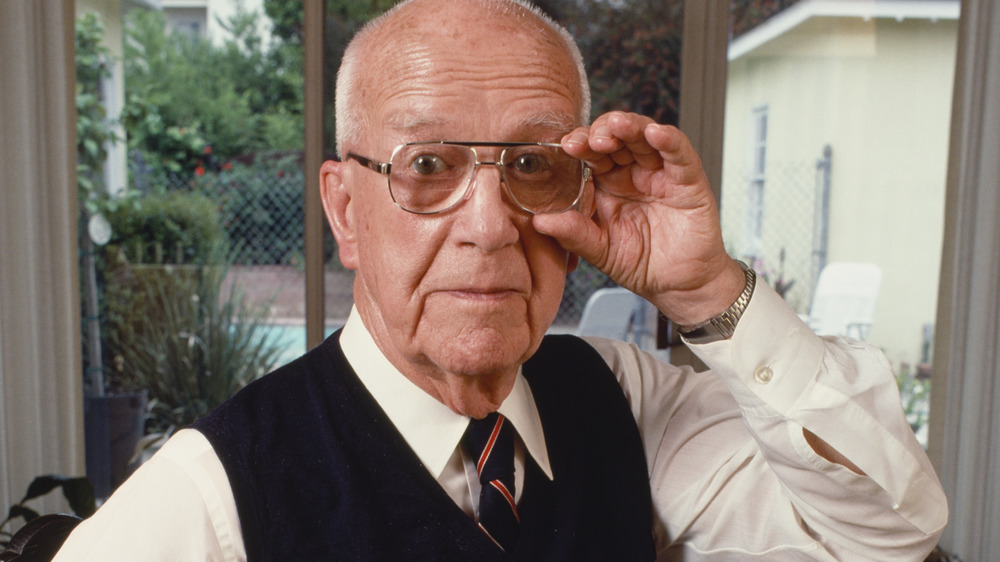

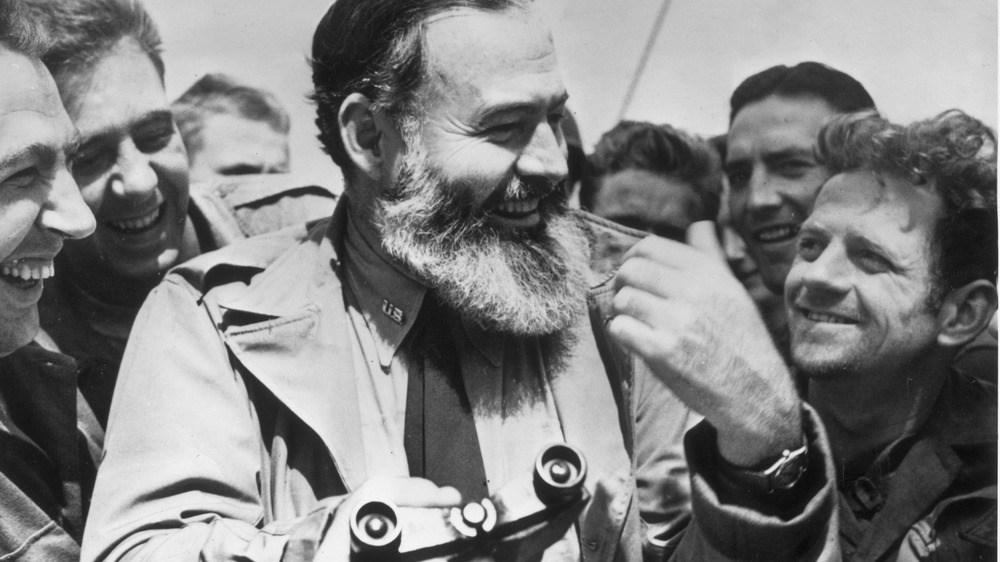

Ernest Hemingway: sometimes, paranoia is there to tell you something's wrong

When it comes to great writers, Ernest Hemingway is at the top of any number of lists. His career — and his life — ended on July 2, 1961. That's when he unlocked his shotgun, walked across his home, and committed suicide.

According to PBS, the obituary originally claimed it had been an accident. It was only later that the real story started to emerge. Starting in the late 1950s, Hemingway had struggled with depression, anxiety, and even disorientation and confusion. His depression grew so severe that he was checked into the Mayo Clinic in December of 1960, and released two months later with best wishes. But they add that his condition continued to worsen, and several suicide attempts were narrowly avoided. Today, Hemingway's diagnosis is a long one: depression, paranoid delusions, bipolar disorder, hemochromatosis, and on top of it all was alcoholism.

There's one more layer to the tale, though. In 2011, Hemingway's longtime friend and biographer A.E. Hotchner wrote a piece for The New York Times, in which he talked about Hemingway's deepening paranoia and his belief that the FBI was out to get him. He saw agents everywhere, and at the time, Hotchner and Hemingway's wife didn't believe him. It was decades before the FBI released their files, and Hotchner learned that his old friend had been 100 percent right.