How The Vanderbilt Family Lost Their Entire Fortune

In the late 19th century, social and technological changes allowed thousands of families to get ridiculously rich and prosper in a period called the Gilded Age, as described by Time. It was an era where flaunting your wealth publicly was all the rage, even in the face of income inequality as millions of other Americans struggled day to day. The Gilded Age was when many of the infamously wealthy families got their start, from the Rockefellers to the Carnegies to the Vanderbilts (via ThoughtCo). But while their legacy is still recognizable today, with their names plastered on universities and cultural landmarks, for many, their fortune has been gone for some time now.

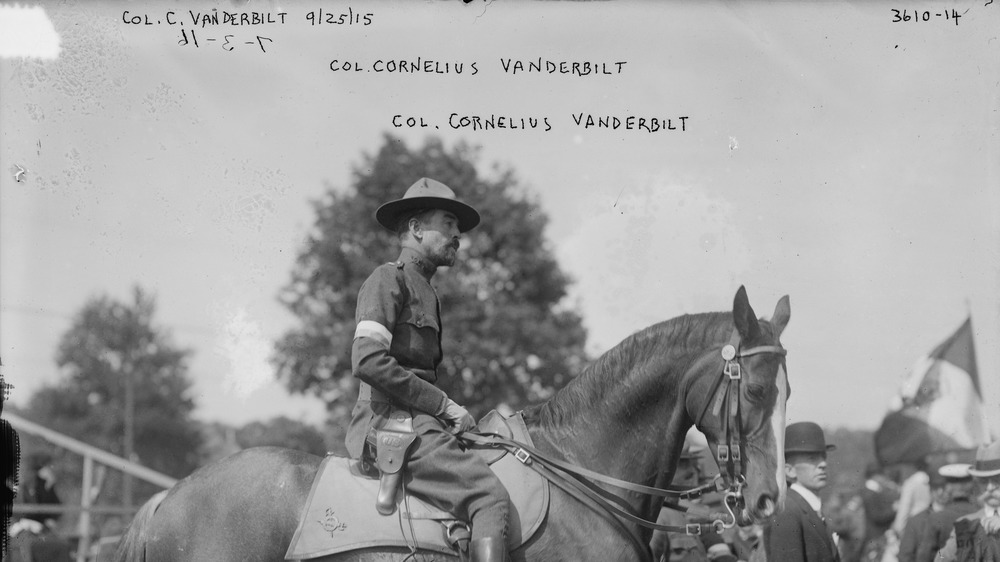

The Vanderbilts, owners of a railroad empire brought to the top by ruthless patriarch Cornelius "the Commodore" Vanderbilt, were once the richest family on the planet. As told by descendant Arthur T. Vanderbilt II in his book Fortune's Children: The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt, not even 30 years after his death in 1877, the Vanderbilt family had fallen off the list of the wealthiest families in the United States. Less than a century later, in 1973, when 120 Vanderbilts came together for a family reunion at Vanderbilt University, there wasn't a single millionaire in attendance.

So how does a family go from being one of the richest alive to having little impact in just a few generations? Here's how the Vanderbilt family lost their entire fortune.

It takes "a man of brains" to hold onto a fortune

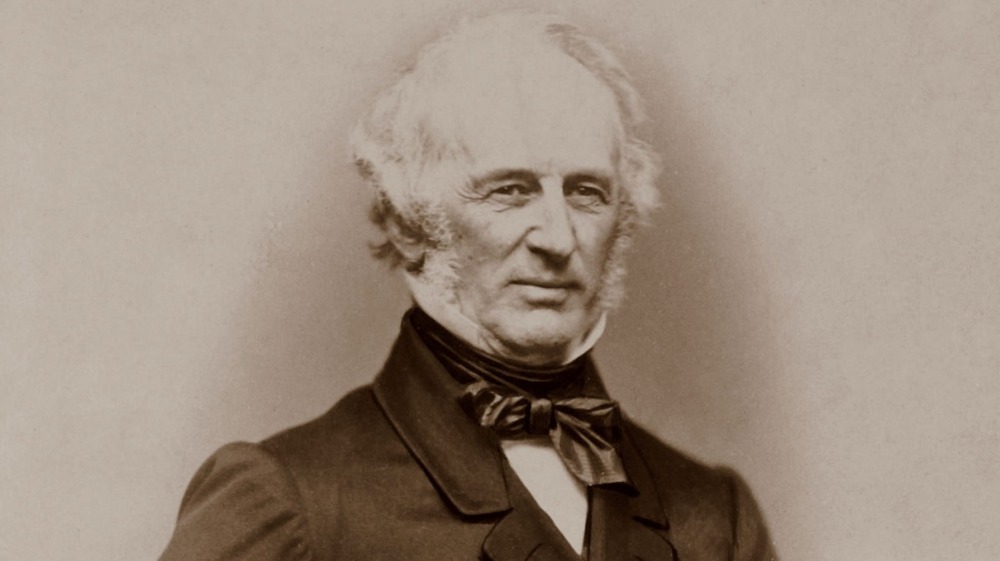

Part of a New York farming family of modest means, Cornelius "the Commodore” Vanderbilt was 16 when he borrowed $100 from his mother in exchange for plowing eight acres of soil, according to Encyclopedia.com. The year was 1810, and the $100 (equivalent to a little over $2,100 today, per the Official Data Foundation) was spent on a boat that he used to start his own transport and freight business.

Over time, the Commodore moved on to invest in steamships and then railroads, and before he knew it, he had built up the shipping and railroad empire New York Central and become the richest American. At the time of his death in 1877, his fortune was valued at $100 million (equal to nearly $2.5 billion today, via the Official Data Foundation), which was more money than was held in the U.S. Treasury at the time, according to Forbes.

The Commodore is said to have told his oldest son, William Henry "Billy" Vanderbilt, "Any fool can make a fortune; it takes a man of brains to hold onto it." Billy took the advice to heart and doubled the family fortune before his death in 1885, but his own descendants would dwindle it all away in just a few decades.

The Commodore's passion for business didn't run in the family

As written by Arthur T. Vanderbilt II in Fortune's Children: The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt, despite the Commodore's great success as a businessman and investor, the man was notoriously harsh and rarely trusted his family with his business and money. His eight married daughters were ignored since they no longer bore the family name, but, of course, that was just one factor that barred his daughters from taking over the business. One time, after a daughter sold her house and asked him to invest the money for her, the Commodore doubled it and then refused to return her money back. "Women are not fit to have money anyway," he said.

By the time of his death, only two of the Commodore's sons were alive, and only the elder, William "Billy" Vanderbilt, had the skills to handle the family business and fortune. The younger, Cornelius "Corneel" Vanderbilt II, was wildly irresponsible and had built up so much debt that the Commodore refused to see him even on his deathbed.

Rather than teaching his children his business skills, the Commodore often left them on their own until they could prove themselves to him. Even Billy, who ended up being the primary inheritor of the Vanderbilt fortune, wasn't allowed to get experience within the railroad empire until he was in his forties. Perhaps it's not that surprising, then, that the future Vanderbilts were unprepared to handle the family fortune.

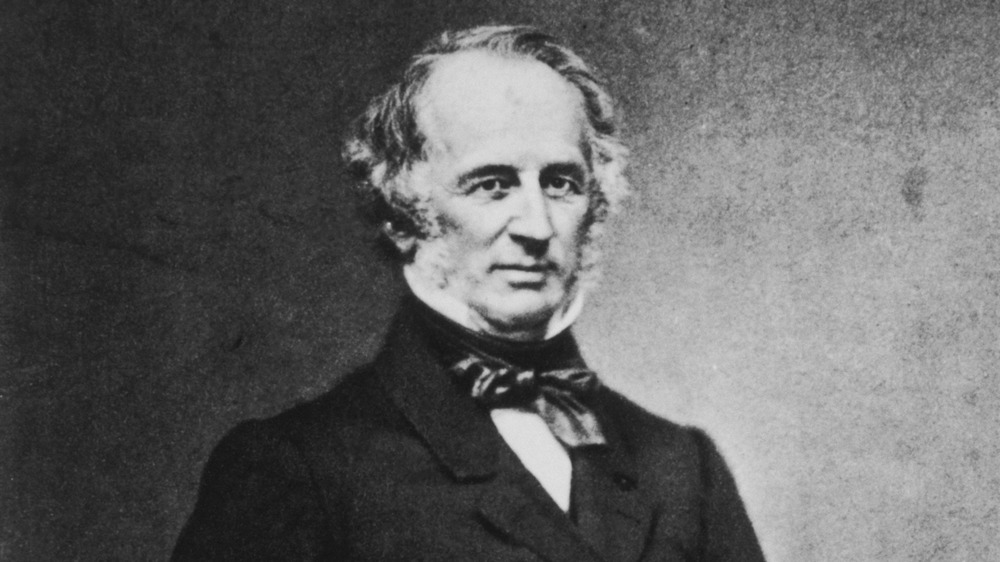

Money brought "nothing but anxiety" for Billy Vanderbilt

When his father passed in 1877, his eldest son William "Billy" Vanderbilt inherited the bulk of his estate, including the 87-percent stake in New York Central, according to Forbes. While Billy was able to prove his business sense to his father, it would be a mistake to assume that the two men had similar characters. As told by Arthur T. Vanderbilt II, the father and son duo couldn't have been more different. Where the Commodore was abrasive and money-hungry, Billy was more inclined to compromise and saw money as a source of anxiety.

Ownership of New York Central came with publicity and conflicts that Billy hated. By 1879, he was ready to sell some of his shares so that he would no longer be considered the sole owner. With the $35 million he made from the sale, he invested in government bonds, a comparatively safe move uncharacteristic of a tycoon.

While Billy wasn't as ambitious as his father, he was obsessed with preserving his wealth and would nitpick over expenses. It is perhaps with smart budgeting and a strong business acumen that Billy was able to double his inheritance to nearly $200 million, making him the richest man in the world by 1883. For him, though, the money was a terrible burden. When he died in 1885, rather than entrusting the fortune to the most business-savvy descendant, he divided it between his two eldest sons so they could share the "heavy responsibility."

The "new money" Vanderbilts bought their way into New York society

Gilded Age New York, the period where the Vanderbilts were most prominent, was dominated by strict social hierarchy. With so many newly rich families popping up after the Civil War and Industrial Revolution, the upper class had to quickly take stock of who could be accepted into their elite society. According to the Museum of the City of New York, the main gatekeeper was Mrs. Caroline Schermerhorn Astor and her right-hand man Ward McAllister. The two created the famous "List of 400," which determined just who could be considered part of New York society. The Vanderbilts, still newly rich and with a reputation for crassness from their patriarch Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt, were not on that list.

Despite this, William K. "Willie" Vanderbilt, the son of Billy Vanderbilt and grandson of the Commodore, was married to Alva Smith, a social-climbing force who was determined to be accepted into New York's high society. She spent millions of her husband's inheritance building a huge mansion on Fifth Avenue's millionaire row, one of the largest homes there at the time. Once the mansion was finished, she spared no expense throwing an extravagant ball that would successfully land Willie and Alva on the List of 400 in March 1883. The cost of the ball was estimated to be over $250,000 (more than $6 million today, per the Official Data Foundation). With expenses like that, it's no wonder the Vanderbilts would soon find their fortune dwindling.

Building grand mansions, townhouses, and estates

In contrast to the Commodore and Billy Vanderbilt, the third and fourth generations grew up ridiculously lavishly and spent their fortunes like crazy. What they loved splurging on were assortments of grand mansions, townhouses, and estates. According to NYC experts at 6sqft, the Vanderbilt family owned multiple Gilded Age mansions on Fifth Avenue's millionaire row, including the massive three townhouses called the "Triple Palaces." They also were prone to bouts of family competition, building huge mansions to rival each other. For example, after Alva Vanderbilt had her "Petit Chateau" constructed, her sister-in-law, Alice Vanderbilt, set out to build an even larger mansion that ended up being the "largest single family house in New York City at the time." Unfortunately, most of these would be demolished in the late 1920s after being sold to real estate developers.

While his sister-in-laws were building some of New York City's biggest mansions, George W. Vanderbilt and his wife Edith looked to Asheville, North Carolina, to build Biltmore. Finished in 1895, the 30,000-acre estate with a 250-room French Renaissance castle took six years and cost nearly $6 million to build, which would be approximately $1.6 billion by today's standards, according to PocketSense. Now open to the public as a tourist attraction and national landmark, Biltmore House is considered the largest privately owned home in the entire country and is still operated by Vanderbilt descendants today.

The Vanderbilts were more interested in philanthropy than business

The Vanderbilts also spent quite a bit of money on philanthropy and exploring their personal interests, especially the Vanderbilts of later generations. The Commodore was known to have made one big donation in 1873: a $1 million gift to Nashville, Tennessee's, Central University, which would then be founded as Vanderbilt University, as explained by Britannica. His son, William "Billy" Vanderbilt, would continue to donate to Vanderbilt University and even left gifts in his will to organizations like the YMCA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (via Britannica).

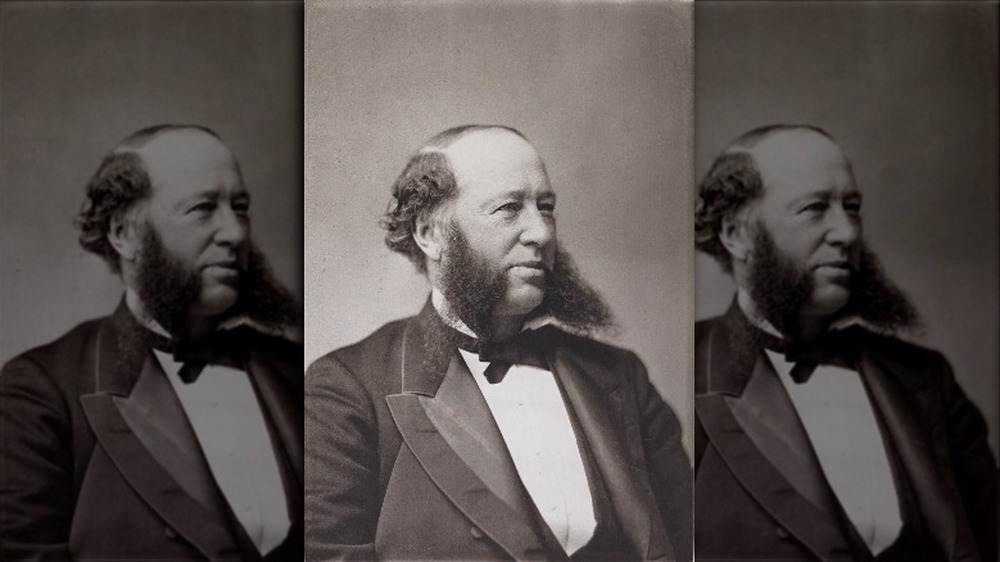

Three of Billy Vanderbilt's sons were particularly known for contributing to philanthropic or cultural causes. According to Britannica, Cornelius Vanderbilt II (not to be confused with the Commodore's second son), who was most prominently in charge of the family investments and businesses, donated huge amounts to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University, Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons. His younger brother, William Kissam Vanderbilt, helped manage the family business for a while but shifted control of the railroads to an outside firm in 1903. After that, he spent most of his time and money on sports and cultural causes, including yacht-racing, art-collecting, and operating the Metropolitan Opera. Finally, the youngest, George W. Vanderbilt, who contributed very little to the Vanderbilts' investments and enterprises, would make large donations to Columbia University, the American Fine Arts Society, and the New York Public Library.

New taxes and the Great Depression

According to ThoughtCo, the Vanderbilts, particularly the Commodore, grew their wealth during an era where business regulation was practically nonexistent. By being able to monopolize entire industries, they became unimaginably rich, with no restrictions or taxes affecting their fortunes. The turn of the century, however, saw a push for more public services, as well as a global conflict that was cutting into trade tariffs, as described by Heritage and ThoughtCo. Needing new revenue sources, the United States government formally introduced the modern estate, gift, and income taxes in the early 20th century. Suddenly, the Vanderbilts' fortunes and inheritances were cut, and their expensive lifestyles became harder to fund.

To make matters worse, when the Great Depression hit, the Vanderbilts had to find different ways to maintain their lifestyles and huge estates. For example, they had to open Biltmore to the public in 1930 to "increase area tourism" and "generate income to preserve the estate" (via Biltmore's Estate History).

While other wealthy families made it through this period just fine, the Vanderbilts' excessive spending and lack of zeal toward growing their family wealth meant that the taxes and Depression affected them much more seriously.

Alfred Vanderbilt's death on the RMS Lusitania

As documented by Geneanet, Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt was the third son of Cornelius Vanderbilt II and the grandson of Billy Vanderbilt. When his father died of a cerebral hemorrhage, Alfred was the primary inheritor of his $72 million estate, according to The Lusitania Resource. Despite being the third-eldest son, Alfred was thought to be the one who would best handle the family fortune. His oldest brother had died young, and his second eldest, Cornelius Vanderbilt III, had been disinherited after getting married without his parents' approval.

Unfortunately, at the young age of 38, Alfred died as a passenger of the RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915, when it was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine during World War I. His early death meant that the family fortune was quickly divided among his wife and young children before it was able to grow significantly under his direction, with his other brothers doing little to contribute to the Vanderbilt fortune themselves after his death.

"Neily" Vanderbilt was disinherited after an unapproved marriage

Cornelius Vanderbilt III, Alfred Vanderbilt's older brother, was well-educated with three degrees from Yale and poised to take over the family railroad business from his father. In 1896, however, at the age of 23, he decided to marry his lover Grace Wilson, a decision that his parents entirely disapproved of, according to the New Netherland Institute. Three years after his wedding, Cornelius would understand just how intensely his family had hated the marriage. In 1899, his father died and, out of his more than $70 million estate, left Cornelius only $500,000. He had, in essence, been disinherited.

As described by The Lusitania Resource, most of the inheritance went to his younger brother Alfred, with his other siblings receiving $7 million each. Out of sympathy, Alfred gave him an extra $6 million, but Cornelius would remain estranged from the rest of his family for decades after. On his own, Cornelius made several technological developments that earned him royalties from patents and lived a lavish life. According to The Gilded Age Era, Cornelius' disinheritance did not deter him or his wife from splurging on mansions, parties, yachts, and other material goods until the early 1940s. It is clear, though, at this point in time, that the Vanderbilt family fortune was nowhere near what it had been before.

Reginald Vanderbilt gambled away his inheritance

As told by Town & Country, Reginald Claypoole Vanderbilt was the great-grandson of the Commodore and the younger brother of Cornelius Vanderbilt III and Alfred Vanderbilt. As the youngest son of the family (per Geneanet), Reginald had little involvement in the family business. He contributed nothing to the Vanderbilt family fortune and instead squandered his own inheritance away on gambling and alcohol until his death.

There are several anecdotes that describe his reckless lifestyle. On his 21st birthday, the night he came into his $15.5 million inheritance, he lost $70,000 gambling. When he was 42, he was told by his doctors that he would die soon if he refused to stop his alcoholic ways. Instead, he continued and even married a 17-year-old socialite named Gloria Morgan. Just a few years later, Reginald died from liver cirrhosis at the age of 45 in 1925. Having gambled away most of his inheritance, Reginald was broke and in debt, leaving behind a widow and baby daughter who would have to live off of the interest payments of the young girl's $5 million trust fund until she was 21.

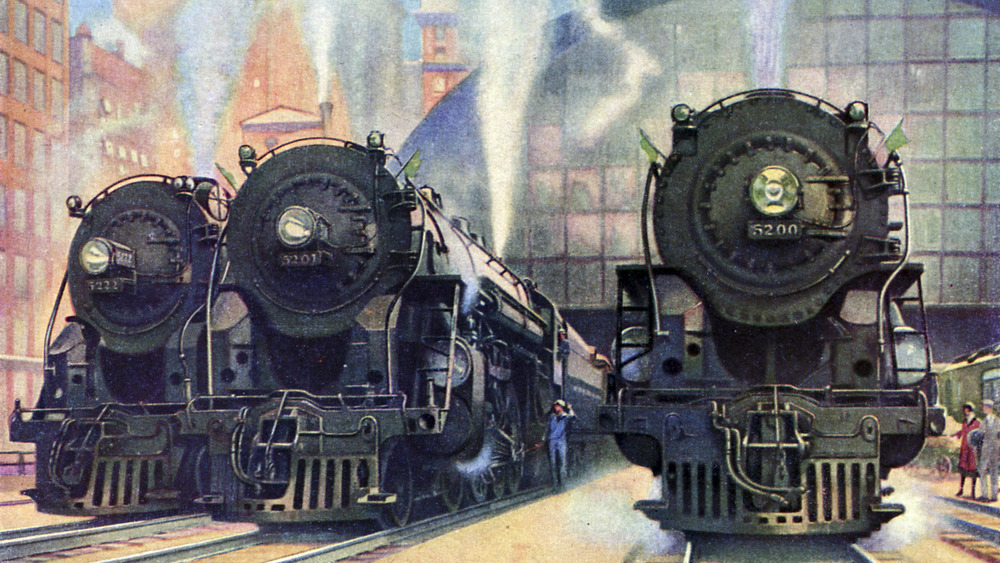

The decline of New York Central and railroads

While the Vanderbilt fortune was being split among more and more descendants who loved to excessively spend their inheritances, the original source of their family's wealth, New York Central, began to decline in the first half of the 20th century, according to Forbes. Peaking in the 1920s, the transport and freight industry began to slump in the 1930s. By the end of World War II, other modes of transportation began overtaking railroads.

The family sold their shares in New York Central, and in 1954, Chesapeake and Ohio Railway's Robert Young took over. However, various owners and mergers couldn't save it. New York Central went from being the second-largest railroad in the United States to having its then-current iteration go bankrupt in 1970. Throughout all of this, the Vanderbilts had failed to establish any significant businesses that would have them maintain their status as one of America's wealthiest families.

Sixth-generation Vanderbilt: Anderson Cooper

The baby girl that Reggie Vanderbilt left behind by his death in 1925 would grow up to be fashion designer, writer, artist, actress, and socialite Gloria Vanderbilt, famous for her jeans in the early 1980s. With her father dead and her young widowed mother something of a ghost herself, Gloria was raised by nannies in France knowing very little about her Vanderbilt family roots and the money that she was poised to inherit, according to her eulogy that was narrated by her son, via ET.

While Gloria had a publicly successful career, she made it clear to her son, news anchor Anderson Cooper, that "there's no trust fund," as reported by the Los Angeles Times. By the late 20th century, barely 100 years after the Commodore had become the richest man in America and his son the richest man in the world, the Vanderbilt family fortune had dwindled into insignificance. When Gloria died in 2019, Cooper inherited most of her estate, which, despite being publicly estimated to be worth $200 million, only had a value of about $1.5 million.