The Spunker Club: The Truth About Harvard's Secret Society

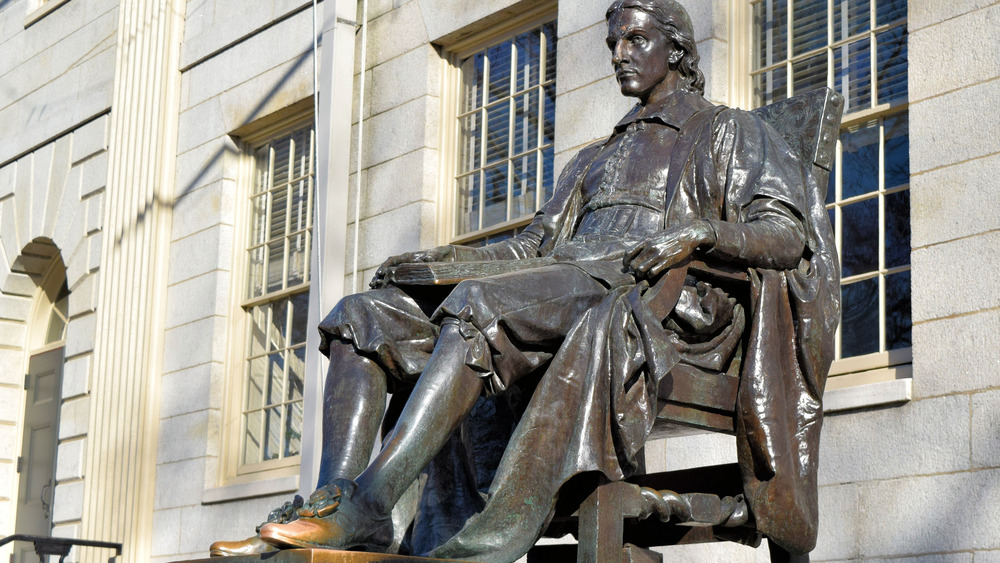

When you think about Harvard kids, you probably picture a bunch of nerds. That's partly correct, but Harvard students have a wild streak to them as well. In fact, per the Harvard Crimson, Harvard undergraduates are encouraged to participate in three traditions: urinating on the John Harvard statue, having sex among the bookshelves of Widener Library, and running naked in Harvard's bi-annual "primal scream." But those traditions all seem tame when compared to what was going on at Harvard in the 18th century. Meet the "Spunker Club."

In 1796, Harvard student John Collins Warren and fellow Harvard undergraduates sneaked into Boston's North Burying Ground in the dead of night. There, they identified a corpse of an individual without any kin, dug it up, and hauled it back to campus. When Dr. John Warren, anatomy professor and father of John Collins Warren, found out about the escapade the next day, he was... proud. "When the body was uncovered, and he saw what a fine, healthy subject it was, he seemed to be as much pleased as I ever saw him," the younger Warren wrote.

You see, Dr. Warren (co-founder of the Harvard Medical School) had also participated in body snatching during his time as a Harvard undergraduate — not as some absurd hazing ritual, but for the advancement of science. In the 18th century, medical students were in dire need of corpses to use as they practiced surgical techniques, and to advance their knowledge of human anatomy more broadly.

Around 1770, Harvard medical students formed a club dedicated to grave-robbing

At the same time, Massachusetts only allowed anatomy students to dissect the body of executed criminals. These corpses were rare, amounting to little more than one body per year. That was hardly enough for medical schools, so these schools began to hire body snatchers — politely referred to as "resurrection men" — to do their dirty work.

Around 1770, a group of Harvard students (including the elder Warren) formed a secret medical society known as the "Spunker Club." The club was never formally recognized by Harvard, and was so hush-hush that members were forbidden to even write its name. One of the Spunker Club's most gruesome activities was emptying Boston graves for medical research. But the club's activities ranged greatly, from the dissection of animals to anatomical lectures using human skeletons. Members of the underground Spunker Club included Samuel Adams' only surviving son, as well as William Eustis, the future Secretary of War under President James Madison.

After several years of scrounging for bodies, the Spunker Club received a godsend: the Revolutionary War. During the bloodshed that resulted from the war, members of the Spunker Club likely collected cadavers from both sides, a practice George Washington referred to as an "abominable crime," per the Journal of the American Revolution. Once the war had ended, the junior Warren lamented the "great difficulty in getting subjects."

Massachusetts cracked down on grave-robbing, and the Spunker Club faded away

By the early 1800s, more and more medical schools were looking for fresh cadavers, so Boston had to hire watchmen to patrol its graveyards. Then, in 1815, the fed-up Massachusetts government passed the "Act to Protect the Sepulchers of the Dead," which made it a felony to disturb a grave or steal a corpse. This act received extreme pushback from the Massachusetts Medical Society, so in 1831, Massachusetts passed the "Anatomy Act," which allowed medical professionals to legally obtain the bodies of the imprisoned, the insane, and the poor.

In the meantime, the Harvard Medical School began bribing New York City officials to ship corpses to the university. With this practice in place, the body-snatching Spunker Club began to fade out of existence — although its exact history is hard to pin down, given the secrecy surrounding the society. Regardless of the Spunker Club's exact end-date, grave robbing continued to be practiced for medical purposes well into the 20th century.

According to Atlas Obscura, when one Harvard chapel was renovated in 1999, forgotten human remains, likely collected by "resurrection men," were discovered underneath. For Harvard students' sake, we hope that the souls of the displaced dead haven't put a curse on the university.